Fall Book Roundup

November 30, 2021

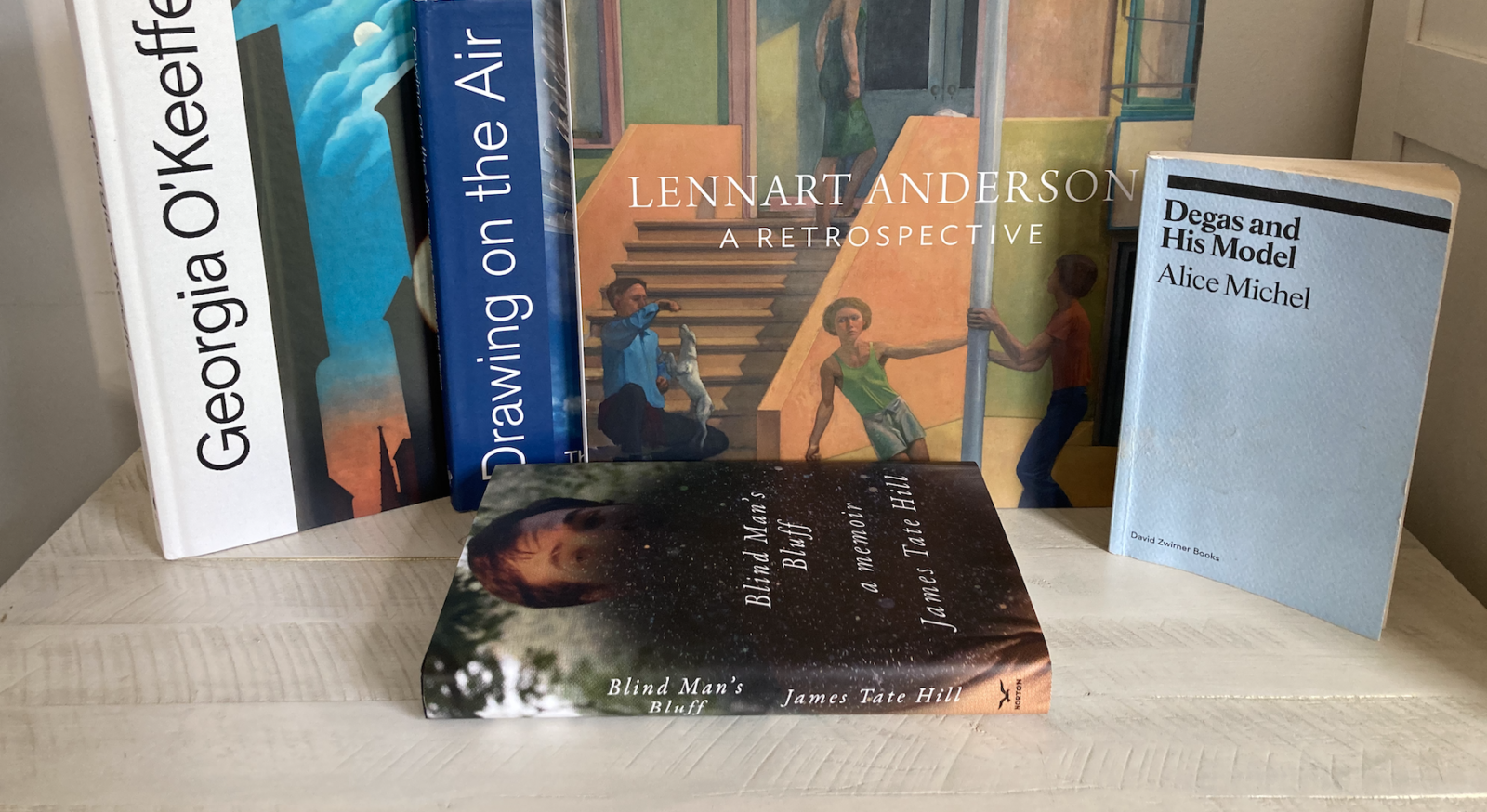

Our fall book roundup includes exhibition catalogs about three artists we’ve written about at the Vision & Art Project; a recently published memoir by James Tate Hill about the author’s attempt to hide his blindness from the world; M. Leona Godin’s personal and cultural narrative of blindness, the translation of a 1919 text about Degas’s studio practices late in his life; and a memoir by poet Stephen Kuusisto, first published in 2013, that, like Hill’s story, delves into why the author wanted so badly to pass as sighted.

Exhibition Catalogs

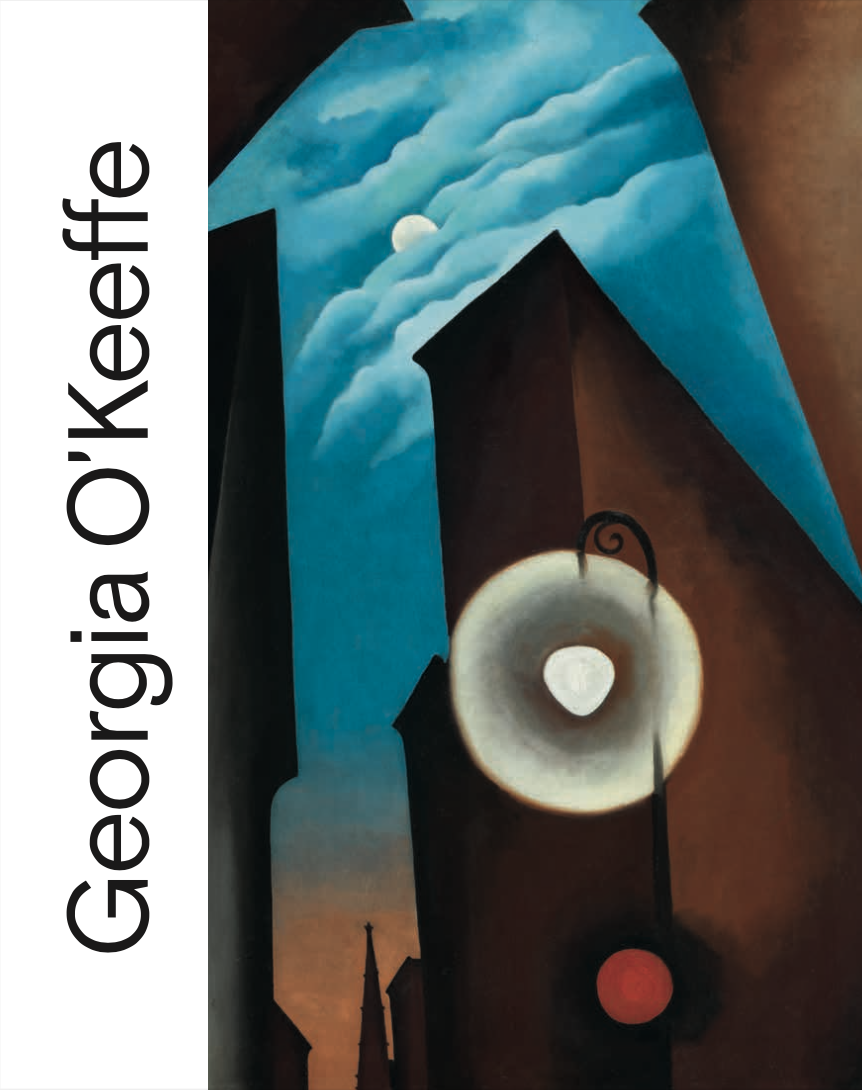

Georgia O’Keeffe

Marta Ruiz del Árbol, Editor

With five Georgia O’Keeffe paintings in its collection, the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza (Madrid, Spain) holds more Georgia O’Keeffe works than any institution outside the United States. Using those five works as a kernel, the museum this year launched Spain’s first O’Keeffe retrospective (April 20–August 8, 2021). After completing its run in Madrid, the exhibit moved on to the Centre Pompidou in Paris (September 8–December 6, 2021), after which it will travel to the Fondation Beyeler in Basel (January 28–May 22, 2022).

Curated by Marta Ruiz del Árbol, curator of modern paintings at the Thyssen-Bornemisza, the exhibition brings together 90 works spanning O’Keeffe’s career. The exhibit’s earliest works are the abstract drawings O’Keeffe executed in 1916 when working as an art teacher in Texas and the last are from the 1970s, including Sky Above Clouds / Yellow Horizon (1976–7), which O’Keeffe painted with assistance, after her vision declined due to macular degeneration. Arranged chronologically and thematically, the exhibition sheds light on the role of movement (journeys, walks, expeditions, etc.) in O’Keeffe’s creative process and foregrounds the artist’s connection to nature.

That such a major exhibition has been presented this year is nothing short of remarkable. The generous, 300-page hardbound catalogue that accompanies it offers some consolation for those unable to attend it in person. Along with 95 gorgeous plates of O’Keeffe’s work, the catalog includes six essays. It affords a fascinating perspective on O’Keeffe, one that widens the lens on a quintessentially American artist and draws attention to the far reaches she traveled in mind, spirit, body, and art. Read our complete review here.

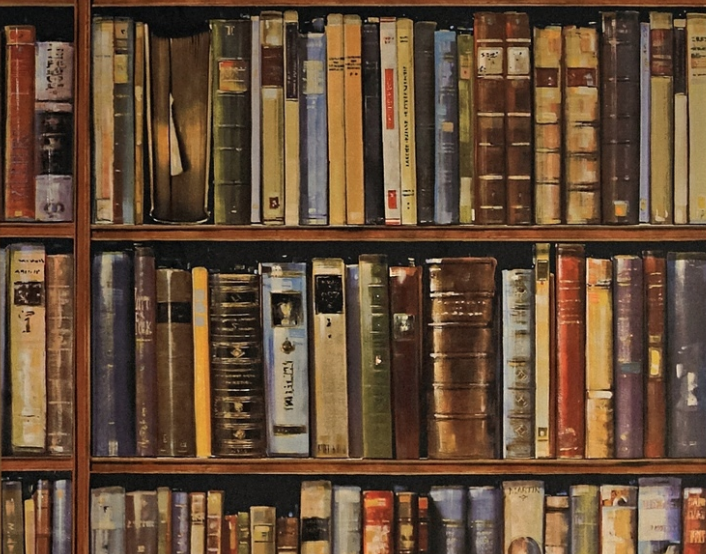

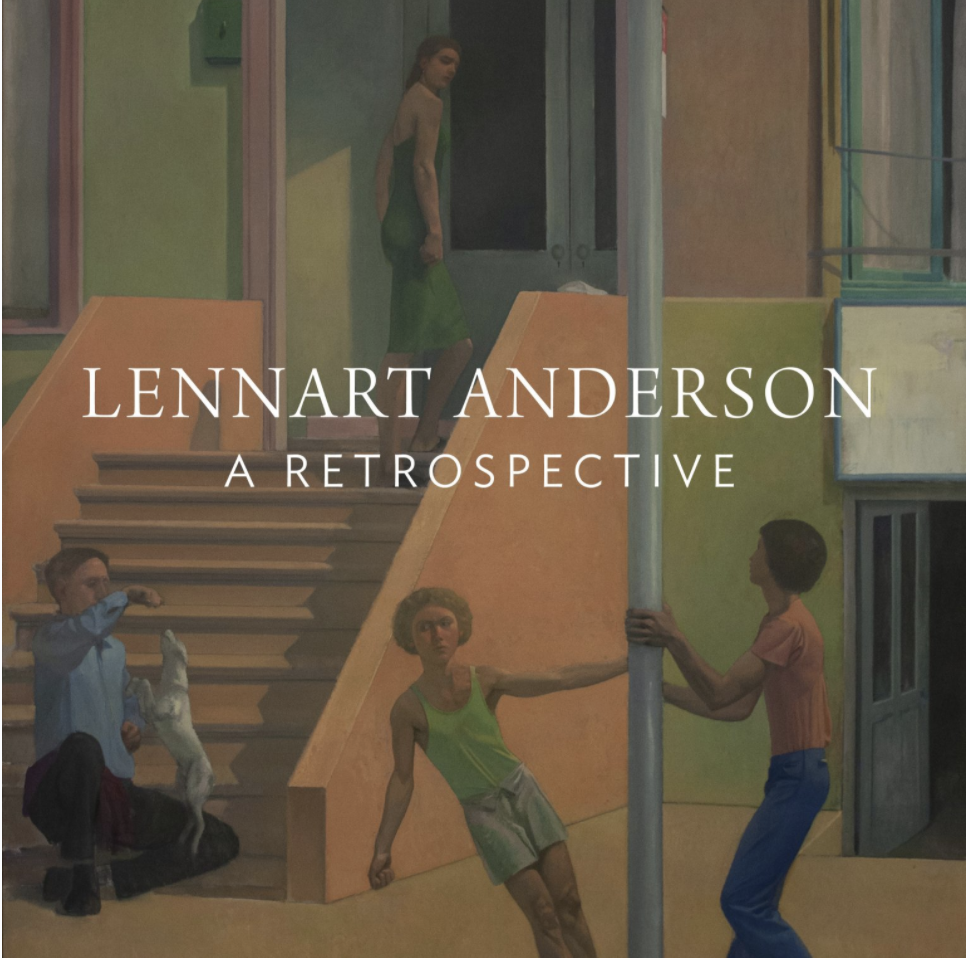

Lennart Anderson

Essays by Paul Resika, Jennifer Samet, Martica Sawin, and Susan Jane Walp

Lennart Anderson: A Retrospective opens at the New York Studio School (NYSS) on October 18 and will be on view until November 28, 2021 before traveling to the Lyme Academy of Fine Arts (January 14, 2022–March 18, 2022) and Southern Utah Museum of Art (June 17–September 16, 2023). Renowned for his mastery of tone, color and composition, Lennart Anderson (1928–2015) was recognized for his modern take on classical modes of painting and taught several generations of painters across his long, highly regarded career.

This retrospective exhibit, curated by Graham Nickson and Rachel Rickert of the NYSS in collaboration with the artist’s estate, presents 35 works spanning Anderson’s career.

A catalog designed by award-winning book designer Patricia Fabricant accompanies the exhibit. It includes four essays that, taken as a whole, contextualize Anderson’s work within the artistic milieu of his era and pay homage to his historical significance as an artist, teacher, and consummate craftsman of painting. Richly illustrated, the catalog includes paintings spanning Anderson’s career, archival photographs and pictures of the artist’s studio, and images of historical paintings that influenced Anderson’s work. As the first major publication about this important American artist, I can’t recommend this catalog highly enough, both for the beautiful reproductions of Anderson’s work (the catalog was printed in Italy), and the insightful essays that illuminate Anderson’s contribution to American art. Read our complete review here.

Memoirs and biographies

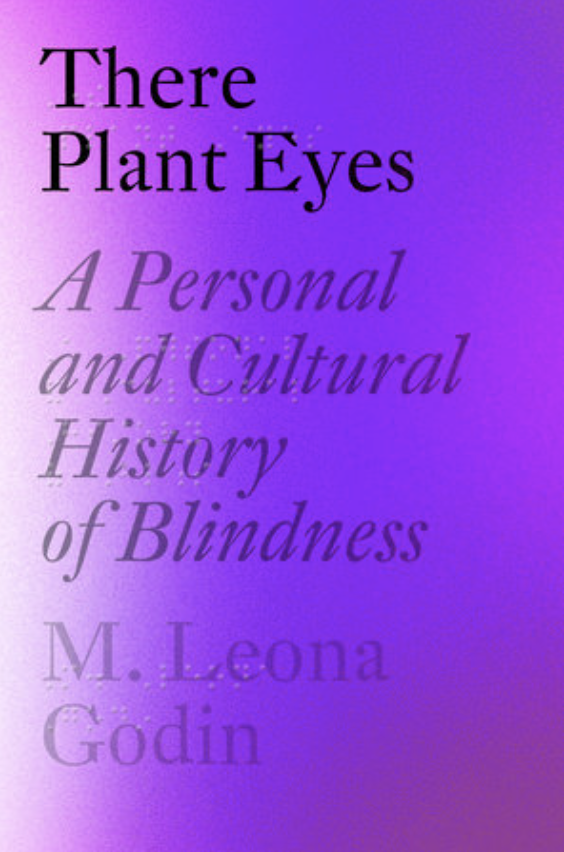

There Plant Eyes: A Personal and Cultural History of Blindness

M. Leona Godin

Around 2006, M. Leona Godin was in a PhD program at NYU in Early Modern Literature when she began to realize that academia was not for her. She’d received a dissertation grant that released her from teaching obligations for a year, and found that she had a lot of time on her hands. Time she used in part, as she relates in There Plant Eyes, to start “running around the East Village and the Lower East Side (with my guide dog), performing at open mics.” It was during this time, too, that she discovered Kim Nielson’s 2004 book, The Radical Lives of Helen Keller, and learned that Helen Keller, along with her teacher Anne Sullivan, performed on the vaudeville circuit for four years beginning in 1920.

Godin, who identifies herself on her website as a blind writer, performer, and educator, began to experience vision problems at the age of ten and gradually went blind due to retinal degeneration. She was astounded to learn about Keller’s vaudeville years. She was also surprised that The Radical Lives of Helen Keller, which sought, as Godin writes, “to chip away at Keller’s saintly blind edifice by revealing just how radical a thinker she really was” seemed to dismiss and treat with disdain Keller’s vaudeville experience.

Godin, meanwhile, considered the experience an integral part of Keller’s real-life complexity. After finishing her dissertation, she wrote, produced, and performed in The Star of Happiness, a play about that part of Keller’s life, in which she used and recast material from Keller and Sullivan’s performances for a 21st century stage.

Godin’s goal in The Star of Happiness, as it is in her recently published book, There Plant Eyes, was to unravel, to challenge, our culture’s notions of visually impaired and blind people. A wide-ranging book, in There Plant Eyes, M. Leona Godin interweaves her story of gradually losing her sight with an analysis of what literature, art, philosophy, science, and the lives of blind people can tell us about the myths, metaphors, and realities of being “blind.” You can find our complete review here.

Blind Man’s Bluff

James Tate Hill

James Tate Hill was a comics-loving sixteen-year old from West Virginia when he was diagnosed with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, a condition that left him legally blind and is the subject of Blind Man’s Bluff. In his extremely down-to-earth memoir, which is both poignant and humorous at the same time, he describes a pattern of denial that repeats itself over and over again in the ensuing years.

As Hill skillfully dramatizes in his book, each time he made a transition in his life (from high school to college, college to grad school, student to teacher), he kept the severity of his vision loss from his new associates and lived an incredibly isolated existence until was eventually able to integrate into a new community. What he calls the “lie” of being sighted that he tries to project interferes most profoundly with his romantic relationships, beginning with his first date in high school when he pretended he could read the menu. Only after a series of crises and losses does Hill acknowledge his blindness to himself and others, thereby changing the dysfunctional patterns that have plagued him and finding love. You can read our complete review here.

Planet of the Blind

Stephen Kuusisto

For the first thirty-nine years of his life, the poet Stephen Kuusisto tried to pass as sighted. He explored this experience in his memoir, Planet of the Blind.

Kuusisto was born with a severe vision impediment called “retinopathy of prematurity” (ROP), more damaging among premature children in the 1950s and ’60s than it is today, since the condition is now better understood and treated. (The oxygen content in incubators in the 1950s and 60s was too high, which caused blood vessel overgrowth.) Though legally blind, Kuusisto is not completely without sight, which is true of most people who are blind, including those with macular degeneration. In Kuusisto’s case, he can see the world in “fragments,” as he says, “like a myopic, darting minnow.” These vestiges of sight made it possible for him to pass as sighted for the first four decades of his life—an effort, which he called an “impossible contest with the sighted world,” that was exhausting, depressing, isolating, and ultimately dangerous.

This memoir, which has become a classic in the years since it was first published in 2013, is notable both for the story Kuusisto tells of the ever-increasing dangers of trying to pass as sighted and for the Kuusisto’s amazing, lyrical descriptions of the world he apprehends. You can find a more in-depth discussion of this book here.

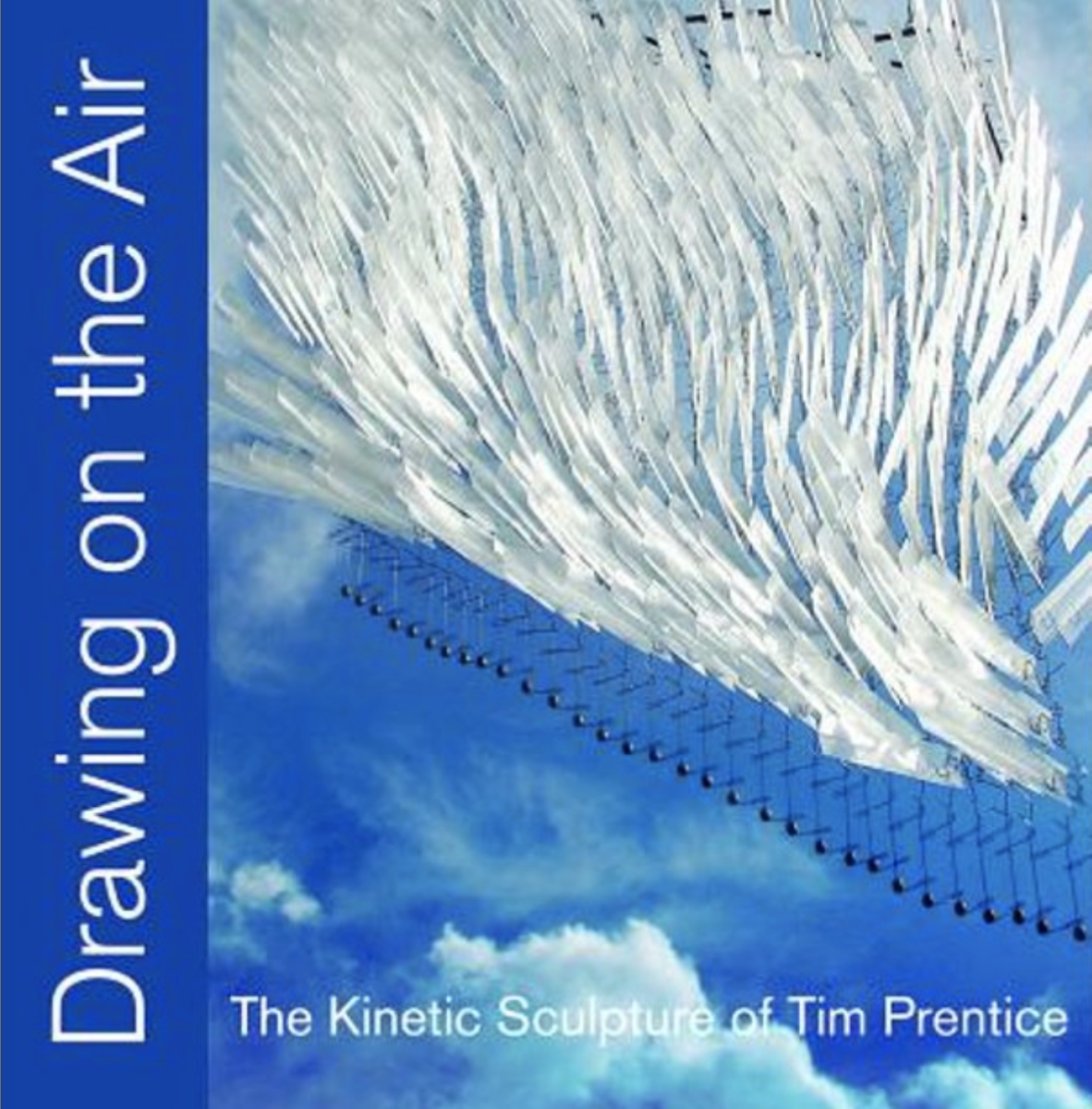

Drawing on the Air: The Kinetic Sculpture of Tim Prentice

Tim Prentice

On a recent fall weekend, Tim Prentice, who we’ve interviewed at the Vision & Art Project, was one of the artists participating in the Cornwall, CT, Open Studios. When we stopped by to say hello, admiring visitors packed his studio and milled around outside, where he’s composed a collection of his kinetic sculptures, creating of his land a permanent sculpture garden.

Prentice had installed himself at the entrance of the barn that, among other things, serves as a showroom for his work. At 91, he is lanky and sociable. Along with selling his sculptures, he was happily selling signed copies of a 2012 book he produced about his work, Drawing on the Air. Though it’s been almost a decade since it was published, it remains a fascinating window into Prentice’s work specifically and kinetic sculpture more generally. Until recently, in fact, it was the only publication available about this significant but under-known American artist. Happily, it’s recently been joined by Tim Prentice: After the Mobile, a small catalog that accompanies his current show on view at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

While photos of Prentice’s sculptures can’t convey the multisensory immersion of experiencing their motion in person, these two publications combine to help bring his richly deserving work to a wider audience. They also hint at what Prentice hopes to communicate through his sculptures: to “slow the viewer down for a minute, hold their attention, draw people out of their own concerns, get them to see something they hadn’t seen in an ordinary day.”

Read our complete review here.

Degas and His Model

Alice Michel, translated by Jeff Nagy

The French painter Edgar Degas died on September 27, 1917, at the age of eighty-three. Two years later, his private art collection and the contents of his atelier were still being auctioned—and setting records—when one of France’s leading cultural journals, the Mercure de France, published an essay in two installments called Degas and His Model.

Written by the pseudonymous Alice Michel, whose true identity remains unknown, it tells about the experience of the artist model “Pauline” posing for Degas in 1910. Translated for the first time into English a few years ago, Pauline’s unflattering portrait of Degas also offers a fascinating window into his studio and working practices late in his life, when he was nearly blind. Although Pauline’s exact identity has never been verified, scholars have typically assumed the text to be rooted in the authentic experience of one of Degas’s artist models. Read our complete review here.

Further Reading

Hedda Sterne’s Recommended Books

Hedda Sterne was a passionate reader. We offer her refreshingly timeless book recommendations as captured in her correspondence with a friend.

Read More

Leave a Comment