There Plant Eyes: A Personal and Cultural History of Blindness

M. Leona Godin

Pantheon, 2021

A wide-ranging book, in There Plant Eyes, M. Leona Godin interweaves her story of gradually losing her sight with an analysis of what literature, art, philosophy, science, and the lives of blind people can tell us about the myths, metaphors, and realities of being “blind.”

Unraveling stereotypes about people who are visually impaired and blind.

Around 2006, M. Leona Godin was in a PhD program at NYU in Early Modern Literature when she began to realize that academia was not for her. She’d received a dissertation grant that released her from teaching obligations for a year, and found that she had a lot of time on her hands. Time she used in part, as she relates in There Plant Eyes, to start “running around the East Village and the Lower East Side (with my guide dog), performing at open mics.” It was during this time, too, that she discovered Kim Nielson’s 2004 book, The Radical Lives of Helen Keller, and learned that Helen Keller, along with her teacher Anne Sullivan, performed on the vaudeville circuit for four years beginning in 1920.

Godin, who identifies herself on her website as a blind writer, performer, and educator, began to experience vision problems at the age of ten and gradually went blind due to retinal degeneration. She was astounded to learn about Keller’s vaudeville years. She was also surprised that The Radical Lives of Helen Keller, which sought, as Godin writes, “to chip away at Keller’s saintly blind edifice by revealing just how radical a thinker she really was” seemed to dismiss and treat with disdain Keller’s vaudeville experience.

Godin, meanwhile, considered the experience an integral part of Keller’s real-life complexity. After finishing her dissertation, she wrote, produced, and performed in The Star of Happiness, a play about that part of Keller’s life, in which she used and recast material from Keller and Sullivan’s performances for a 21st century stage.

Godin’s goal in The Star of Happiness, as it is in her recently published book, There Plant Eyes, was to unravel, to challenge, our culture’s notions of visually impaired and blind people. In the case of The Star of Happiness, that meant complicating who Helen Keller was—challenging the saccharine presumptions our ocularcentric culture has inherited about her, which are based on long-standing stereotypes about what it means to be blind. (More about the term “ocularcentric” below.)

Contrary to many who thought Keller was exploited, Godin discovered that Keller took to the stage of her own free will for practical financial reasons. In doing so, she acted as an autonomous being. She expressed her progressive political views, managed a career among people who sometimes tried to swindle her, and enjoyed being part of what Keller deemed the “amusing” world of the theater. An important part of Godin’s interpretation of Keller’s vaudeville act was the comedic tone she brought to some of the “schmaltzy” and “sentimental” songs and speeches that Keller and Sullivan were known to have delivered. This comedic tone was helpful, Godin felt, in cutting through and unraveling stereotypes about people who are visually impaired and blind.

A multilayered network of associations

Godin tells about this experience about midway through There Plant Eyes, in a chapter entitled “Helen Keller in Vaudeville and in Love.” As she does in the rest of the book, this chapter is a fascinating weave—a multilayered network—of associations. While sharing details about her own journey, Godin also reframes Keller’s biography, and unearths and critiques underlying assumptions about blind people (“Accusations [that Keller was exploited] seem to me fraught with assumptions about what a blind person is supposed to do and be,” Godin writes, “assumptions that insist blind people be poets and prophets, saints or beggars, not lowbrow entertainers”).

She also shows the tracks and traces of influence that connect us all in a continuum of texts and beliefs over time. Along with her own and Keller’s stories, she brings in Charles Dickens’s sentimental account of Laura Bridgeman (the first deaf-blind American child to gain a significant education), the portrayal of disabled people by able-bodied actors, the discrimination that visually impaired actor Marilee Talkington has experienced, what sighted people think it means to “look blind,” and much more.

This strategy of both recasting and reweaving cultural history through the perspective of vision and blindness is one that Godin systematically employs from the beginning of her book, as she takes us through time in Western culture. From Homer to Helen Keller to Stevie Wonder, from The Odyssey to Game of Thrones, from the invention of braille to human echolocation, her goal is to reveal and question the hurtful ocularcentrism at the heart of our culture. She also posits a potentially different worldview, one in which the sighted and blind, vision and blindness, are in fact intimately connected to one another and mutually important to us in our understanding of ourselves and our world. Her reading of Western culture, which is never simplistic, is fascinating and brilliant. It’s a book whose chapters can be read separately alongside the texts to which it refers, or that can be read in its entirety to gain a new appreciation for the role of sight and blindness in our thinking about the world.

The Ocularcentrism of Western Culture

Godin first encountered the concept of ocularcentrism in Martin Jay’s book Downcast Eyes. A concept that is central to There Plant Eyes, for Godin it connotes a way of being that permeates our culture, one that assumes that being visual is the only way to be. This worldview is damaging to visually impaired and blind people because it stigmatizes them and deprives them of the opportunity to participate fully in the world. But it’s also damaging to the fully sighted, as Godin points out, because the world is diminished when only the perspectives and insights of the able-bodied are considered fully valid.

Her opening chapters look at representations of the blind in literature. Starting with Homer, she tracks the trope of the blind bard, as well as the blind prophet-seer and superhero as it moves from The Iliad and The Odyssey (8th century BCE), through Sophocles’s Oedipus plays (429 BCE), Christian texts, Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of King Lear (1606), and Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). As her allusions to many contemporary texts demonstrate, the blind bard, blind prophet-seer, blind superhero is by no means a thing of the past but very much alive today. Her problem with these metaphors is that they weigh on blind people—flattening their diverse, messy, complex, and interesting lives.

Godin moves from a discussion of literature to talk about the scientific and philosophic ideas of the 17th century that “made plain the weakness in human vision.” The development of telescopes and microscopes, for instance, showed that even a fully functioning human eye was unable to perceive the cosmos on one hand and the microscopic universe on the other.

As she moves into the world after the Enlightenment, she focuses on the lives and experiences of blind people: the English scientist and mathematician Nicholas Saunderson (1682–1739), the Viennese musical prodigy Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759–1824), the blind students of Valentin Haüy (founder of the first school of the blind, 1745–1822), who entertained the court of Versailles during the winter of 1786, Louis Braille (inventor of braille, 1745–1822), James Holman (the “blind traveler,” 1786–1857), and countless other blind scientists, adventurers, and artists who have added much to our culture.

What distinguishes Godin’s discussion throughout is not only the abundant network of interconnected references, but her tone—often irreverent and in-your-face, which is also how she characterizes the performance art that she uses to similar effect to unravel stereotypes about the blind. To wit, when she talks about main characters in literature going blind, she writes:

Whenever the calamity of blindness—temporary or permanent—drops suddenly upon the head of a main character, you can pretty much bet your bottom dollar that that character will learn something very important—a life lesson that could not have been seen with working eyes…

I have thought about this lesson—a favorite of books, movies and television shows—quite a bit in recent years and have cried out to the blank heavens that I feel as though I’ve learned what there is to be learned from blindness, and it would suit me fine to now reenter the sighted world, exuding my understanding like a happy blue aura of humility and wisdom. Because if blindness is actually a fix for wrongheadedness and sinfulness then all of us blind should be quite infallible and angelic, right?

But as Godin knows and makes clear to us in this book, blindness is not a fix for wrongheadedness and sinfulness, and to be blind is not necessarily to be a prophet or seer. Many fully sighted people profoundly fail in their ability to see and many visually impaired people see something of the world. Her book is a call to understand the complex continuum between seeing and blindness. It’s also a call to give blind and visually impaired people the right to exist in a world that doesn’t insist upon vision as a primary tool of understanding.

A note on the audiobook

In addition to the print and digital copies of There Plant Eyes, an unabridged audiobook, read by the author, is available at Audible.

M. Leona Godin’s writing has appeared in The New York Times, Playboy, O Magazine, Electric Literature, Catapult, and other print and online publications. She produced two plays: “The Star of Happiness” about Helen Keller’s time performing in vaudeville, and “The Spectator and the Blind Man,” about the invention of braille. Godin holds a PhD in English, and besides her many years teaching literature and humanities courses at NYU, she has lectured on art, accessibility, technology, and disability at such places as Tandon School of Engineering, Rice University, Baylor College of Medicine, and the American Printing House for the Blind. Her online magazine exploring the arts and sciences of smell and taste, Aromatica Poetica, publishes writing and art from around the world.

Further Reading

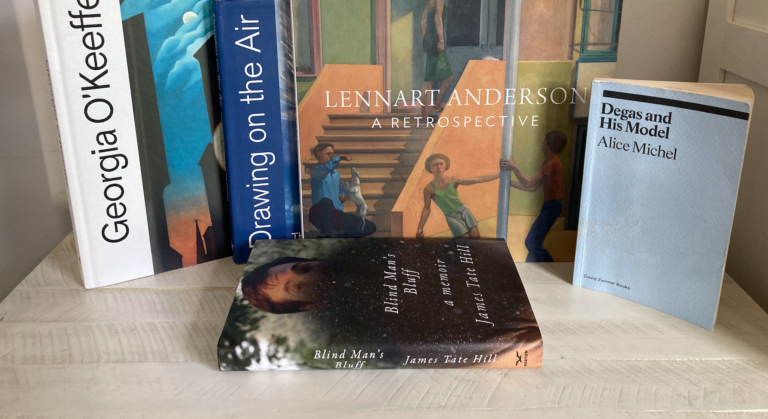

Fall Book Roundup

Books for reading and gifting this fall, including exhibition catalogs and memoirs about vision loss.

Read More