Lennart Anderson: A Retrospective (Exhibition Catalog)

Essays by Paul Resika, Jennifer Samet, Martica Sawin, and Susan Jane Walp

Estate of Lennart Anderson / Leigh Morse Fine Arts, 2021

A catalog designed by award-winning book designer Patricia Fabricant accompanies the exhibition, Lennart Anderson: A Retrospective, which opened at the New York Studio School (NYSS) on October 18, 2021 before traveling to the Lyme Academy of Fine Arts (January 14, 2022–March 18, 2022) and Southern Utah Museum of Art (June 17–September 16, 2023), where it is now on view. Renowned for his mastery of tone, color and composition, Lennart Anderson (1928–2015) was recognized for his modern take on classical modes of painting and taught several generations of painters across his long, highly regarded career. This beautiful catalog includes four essays that, taken as a whole, contextualize Anderson’s work within the artistic milieu of his era and pay homage to his historical significance as an artist, teacher, and consummate craftsman of painting.

The introductory essay, “Lennart Anderson, a Painter for All Time,” is by art historian and critic Martica Sawin, who reflects on what she sees as two of the most striking aspects of Anderson’s career as a painter: his drive for perfection and what she calls his “non-doctrinaire inclinations.”

Taking as a starting point a conversation she had with Anderson near the end of his life, when he told her he made a bargain with the devil by becoming a painter, she poses the question of what motivated his “lifelong drive for perfection.” In answer to this, she sees Anderson as having in some ways worked from a “mixture of motives,” from his aspirations to capture the essence of a thing from direct observation to his perseveration on the age-old search for “a glimpse of a phantom Arcadia.” Yet, she believes that beneath that, what drove Anderson regardless of subject or genre was “Painting itself” as she writes, a word rife with permutations, explicit and implied, including “action,” “object,” “medium,” “commitment,” and “dedication,” all of which occupied Anderson’s attention.

Sawin sees his effort as being singularly unique in that he managed, as she says, “to steer his own course through competing influences to arrive at a hybrid mode of representation that was distinctly his own.” She characterizes this hybrid as an alternation between the “observed” and the “conceptual” and suggests that it is at the kernel of what has delivered Anderson’s work to “posterity.”

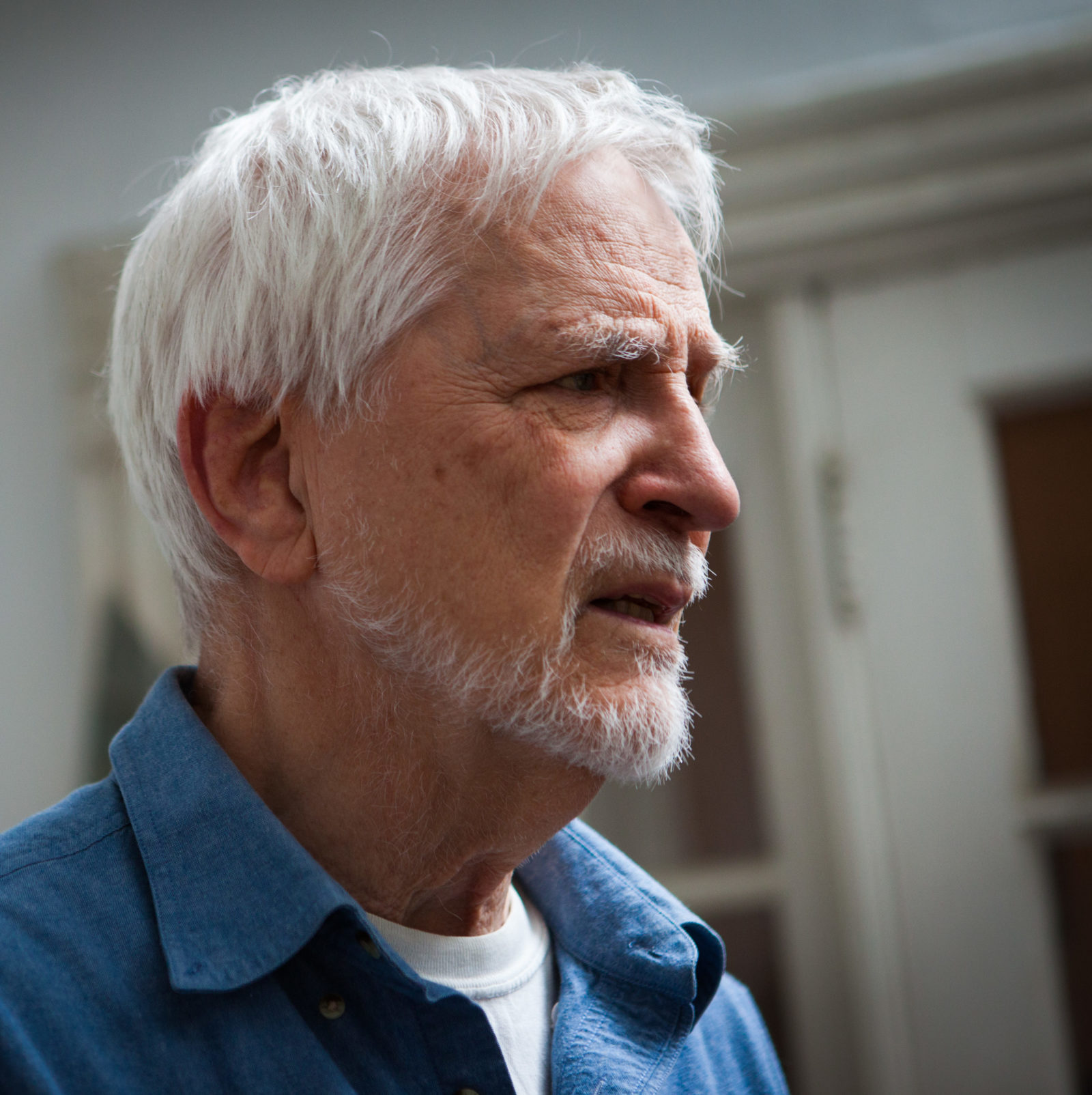

In the second essay, “Remembering Lennart Anderson,” painter Susan Jane Walp presents an altogether different perspective on Anderson, one rooted in the remembrances of a student in one of the first generations of artists he taught. Walp eventually became Anderson’s colleague and friend, and she bookends her essay with her first and last encounters with him. She tells about meeting him in 1968 at a summer painting program run by Boston University. He painted with his students, and so she had an opportunity to witness first-hand how he worked. Fascinated by his quiet attentiveness, astonished by the subtle, “unnamable” colors he mixed, introduced to his concept of tones, Walp writes movingly of how her studies with Anderson caused her to see the world anew and inspired her to devote her life to painting. Equally moving is when she says goodbye to him a few months before he passed in 2015.

She also reminisces on other encounters she and Anderson had over the years, all of which were permeated with Anderson’s uncanny insights into painting and rigorous, precise attention. Reflecting on a conversation she once had with him about Elizabeth Bishop’s criteria for evaluating the quality of poems (accuracy, spontaneity, mystery), Walp writes:

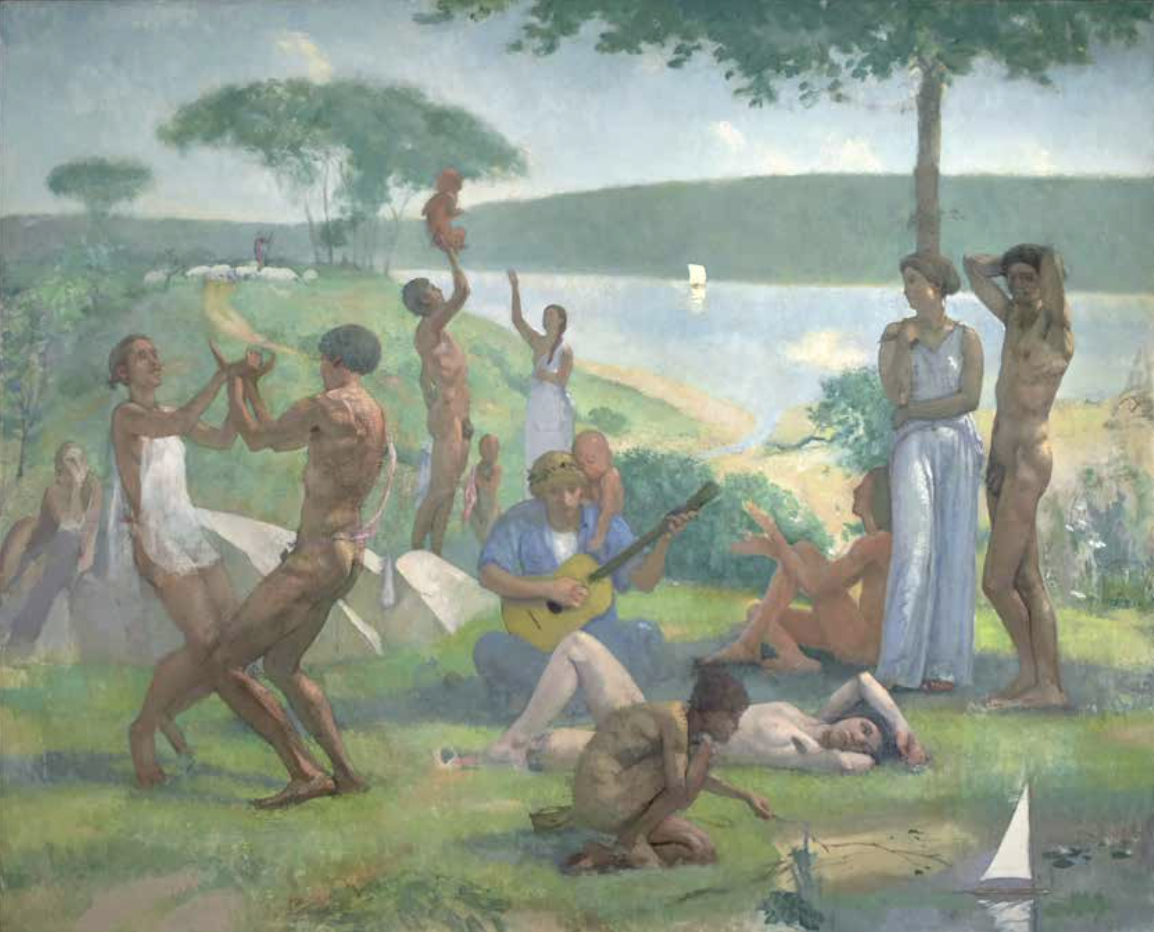

“I am just now seeing how well they apply to his Bacchanal: the accuracy of the proportions of the figures and the rightness of the space they inhabit, from foreground back to the most distant tree; the spontaneity of the brushwork, so freely carrying a feeling of light and movement; the undefinable sense of mystery, a kind of shadow world of forms and shapes, some things known and others not.”

Jennifer Samet, an art historian, curator, and writer, interviewed Anderson in his Brooklyn studio in 2002 as part of her “Interview with Artists” series. The catalog includes an edited version of the interview, with a preface in which Samet reflects on what most strikes her about Anderson as she thinks back on knowing him. She offers a lexicon of adjectives and nouns to describe her most indelible impressions of him—“dedication,” “doubt,” “provocation,” “tough critic,” “empathetic gaze.”

In the interview itself, Anderson fills in some of the details about his life and career formerly alluded to by Sawin. It’s wonderful to hear Lennart’s voice as he talks to Samet about how painting was everything to him from the time he was a child: “Anything that was painted interested me. It could be the stupidest calendar art. If it was put down with paint, I would cross the street to see it.” He also talks about his early years as an emerging artist, his working methods, and what he’s after in a painting—invaluable details that Samet captured in her interview from an artist who did not generally talk at length about his work and working methods.

The catalog closes with a lyrical homage written by Anderson’s decades-long friend and fellow artist, Paul Resika. Constituting a mere page of printed text, Resika strings together quotes, vivid observations and his own personal feelings about Anderson and his work. Links are associative, creating an essay that, like a great poem, to borrow from Sawin, delivers to posterity an enduring image of a great artist and man.

Richly illustrated, the catalog includes paintings spanning Anderson’s career, archival photographs and pictures of the artist’s studio, and images of historical paintings that influenced Anderson’s work. As the first major publication about this important American artist, I can’t recommend this catalog highly enough, both for the beautiful reproductions of Anderson’s work (the catalog was printed in Italy), and the insightful essays that illuminate Anderson’s contribution to American art.