Renewal and Possibility

January 03, 2023

Vision loss can be overwhelming and debilitating; yet, as with any challenge or limitation, it offers the possibility of renewal. The French painter Edgar Degas (1834-1917), when faced with increasing vision loss due to macular degeneration, described in letters to friends how he was forced to innovate and develop new ways of painting.

A late pastel of Degas’s, Three Dancers in Yellow Skirts (detail above), shows Degas problem solving how to capture the feeling and spirit of place through his diminished eyesight.

As we consider this upcoming year, we turn to the words and works of several visual artists, who, like Degas, in the face of losing the faculty they depend upon most, demonstrate resiliency, adaptation, and innovation.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

“The difficulty of seeing makes me feel numb. … I dream nevertheless of enterprises; I am hoping to do a suite of lithographs, a first series on nude women at their toilet and a second one on nude dancers. In this way one continues to the last day figuring things out.”

One of Degas’s late life models described his painstaking commitment to continuing to work despite vision loss. By that point, he had given up painting and printmaking almost entirely for sculpture. As she recounts in a book published shortly after his death, Degas could only vaguely see her when she was posing for him. As a result, he would have to get up and touch her when he needed to check such things as the position of a joint, returning to his work to mold what he had felt in clay. Other times, he would take measurements using a reduction compass. Endlessly, day after day, he shaped and re-shaped his work to create a similitude between what he depicted and what he apprehended using both his faltering vision and sense of touch.

Erika Marie York (b. 1990)

“Creating art is supposed to be about your unique perspective. I don’t understand what being able to see has to do with it, because even if a person were completely blind, they’d still be able to create art from their perspective. Creating art isn’t only for able-bodied people.“

Erika Marie York was in elementary school when she began to lose her vision to Stargardt’s disease. With her parents’ encouragement, she took art classes and workshops when she was growing up. She credits this experience with giving her confidence in her ability to make art in spite of a vision impairment.

York feels that art has to do with sharing one’s perspective, which isn’t dependent on perfect vision. Largely shaped by her eye condition, her distinctive painting style—which includes large canvases, bold lines, bright colors, and figures often lacking facial features or wearing glasses—is inspired by what she sees.

Robert Birmelin (b. 1933)

“Painting with my vision this way is more difficult. I have tried to work on a couple small canvasses and, though I can’t say I’m seeing it blurring, I’m not seeing it well. That’s why most of my work in the last couple years has been graphic. With a pen—the black, white contrast—I can see, I can draw. I also use watercolor with a basic a linear underpinning, but I use very limited color.”

Since being diagnosed with macular degeneration in 2016, Birmelin has found it harder to paint as he characteristically had in larger scale in acrylics. As a result, he’s now relying more on drawing. In doing so, he’s returning to a mode of artistic expression that was crucial to him when he was just starting off as a young artist and was using drawing, as he wrote in 1963, to “make contact with the nature of things:”

Philip Perkis (b. 1935)

“I think a lot of what I see almost has to do with memory, or something like that. And that my pictures have changed in the last years since The Sadness of Men book (2008). … [I]n a way [they’re] simpler and less intellectual and more emotional and more addressing some of the sadder issues of life than they did before. And I think all that’s affected by the vision.”

In 2021, due to increasing vision loss, Perkis consciously made his last photographs, a series of 60 pictures. Though he is no longer making photographs, he has continued to seek through writing a correspondence between his inner life and what he has seen. Some of his writings are forthcoming in ar, a second book collaboration with his wife, the artist Cyrilla Mozenter.

Lennart Anderson (1928-2015)

“Because of my vision, I’m using my life now when I paint. I mean by that, all of the painting that I have ever done.”

As Anderson’s vision declined, he continued his daily rituals in studio, prepping canvases, sorting through drawings, sitting in contemplation studying the painters from the past like Velasquez whom he most admired. He also continued his lifelong interest in painting portraits of his friends. Here, a portrait of the painter Rita Natarova, whom he painted over the course of several days in his studio, chatting, measuring, looking back and forth from canvas to subject.

Robert Hamilton (1917-2004)

“Generally speaking, macular degeneration is an old age disease—the eyes are wearing out. I can see all around, but I can’t see in the middle. It’s a blur in the middle. If you fall off a cliff, you may as well try to fly. That’s my new motto.”

Hamilton’s improvisational approach to painting served him well in the last years of his life, when he had no vision in one eye and blurred central vision in the other. He abandoned large canvases and worked instead on 16 x 16 and 24 x 24 inch squares, creating paintings that were more mysterious and chromatic than ever.

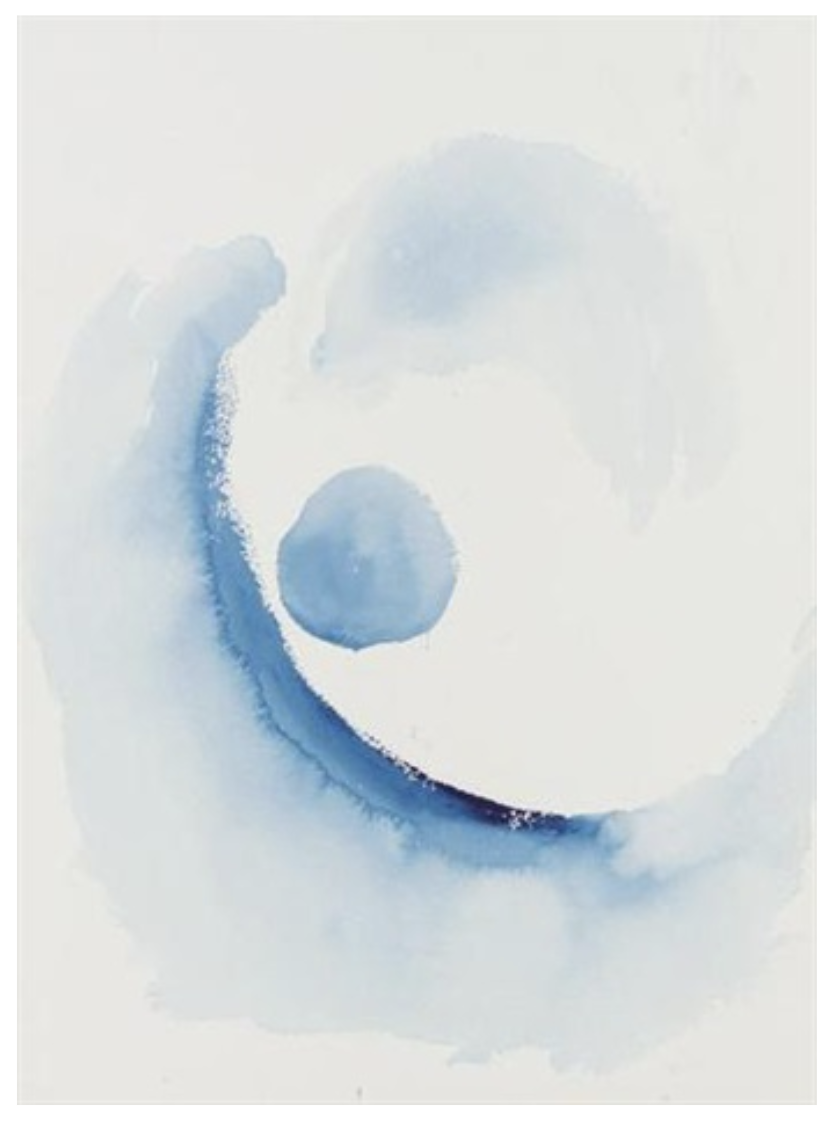

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986)

“When my eyes began to not see sharply as they had for 80 years and the world began to turn grey, I was bothered and gradually stopped working. In time, I was surprised that this world could sometimes be beautiful in a new way and began to think — how could I start again and begin to paint this new world.”

Because of vision loss, O’Keeffe made her last unassisted oil paintings in 1972. In one, Black Rock with Blue Sky and White Clouds, a stone dominates the canvas, a sliver of blue sky and clouds behind it. In another, The Beyond, a wide band of darkness at the bottom of the canvas creeps toward the horizon line. After abandoning oils, she continued to draw and paint in watercolor up until her death. Her final works look back to the abstractions she did in 1915-1918, as if in homage to the distinct visual language she developed then. In the last few years of her life, she also worked in clay.

Tim Prentice (b. 1930)

“I didn’t realize how much I could do with just feel. You can see with your fingers, in other words. I mean, for instance, people do their hair behind their head. They don’t think about it, don’t have to see it. They don’t have to look at their shoe to tie it. We have all these things that our fingers know how to do.”

Prentice was diagnosed with macular degeneration around 2000. As he describes in a 2020 oral history with The Vision & Art Project, in the years since, the disease has become second nature for him. In fact, he says he is “hardly aware” of his vision loss. He’s able to do many things by feel, uses four levels of magnification when he is working in his studio (which he does nearly everyday), and sometimes finds that, in certain circumstances, seeing less well is an advantage, since it better allows him to apprehend the whole.

William Thon (1906-2000)

“My eyes are in my fingers.”

Thon was diagnosed with macular degeneration in 1991. A few years later, he demonstrated his post-macular method of working at a forum on visual impairment at the Farnsworth Art Museum. The painting he finished is above.

Using his hands, Thon navigated by feel from the front of the demonstration table to the back, faced his audience, and began to paint. On the table was a blank sheet of paper. He spritzed it with water, caressing the surface in circular motions, seeming to take stock as a dowser might of what lay beneath. Picking up a brush, he said, “My eyes are in my fingers.” He pulled generous pools of black paint horizontally from left to right. He leaned down close to the surface, his nose inches from the paper, and began to blow softly, so that the paint began to quiver. With a putty knife, he gently scraped upward from the bottom of the paper, revealing the trunk of a birch tree. This gesture he repeated until several trees stood in a wood. Then, with a thinner knife and slightly different gesture, branches. It was magic.

Milford Zornes (1908-2008)

“When eyes fail, the spirit can take over. After all, the eye is only the instrument for seeing. It is through the mind and spirit, fed and served by the senses, that one’s life is lived with understanding and reward.”

In an essay Milford Zornes wrote about his vision loss, he describes his initial depression and grief upon learning he had macular degeneration, then his slow adaptation to the disease over time. As he adjusted to his limitations, he recounts taking less for granted and valuing “every view and every opportunity to see.” He would return from travel with more impressions and memories than before, impressions “as clear in my mind as any I have ever experienced.” He came to understand that, in a sense, he had always been partially blind.

As this painting demonstrates, in his post-macular work, contour lines are like calligraphy, placed with a masterful touch that comes from a lifetime of careful observation, bringing life to soft shapes of color and value.

Advocacy, Education, Inspiration

Our mission at the Vision & Art Project is to give greater visibility fo the overlooked influence of vision loss from macular degeneration on historical and contemporary artists. We strive to ensure the legacy of individual artists, to educate the public about macular degeneration, vision, and art, and to inspire a deeper respect for the human capacity to adapt and change. Our hope is that the work we present provides incontrovertible evidence that, even with compromised eyesight, the visual world remains beautiful and within reach.

Comments

So inspiring for people suffering from various diseases.As a person diagnosed with wet macular degeneration,I am approaching my rug art in a proactive and exciting exploration of new ways to increase my creative endeavours.Thank you for these inspirational glimpses of other artists who create beauty and demonstrate courage and growth in their art form.

We’re glad our website has inspired you. Thank you for reaching out to let us know your thoughts. We are wishing you all the best as you adapt your working methods in response to your macular degeneration.

Leave a Comment