From the Archives: How Lennart Anderson Made a Late Masterpiece

June 29, 2023

In celebration of our 10th anniversary we are highlighting articles from our archives. We first published “How Lennart Anderson Made a Late Masterpiece” on October 17, 2020.

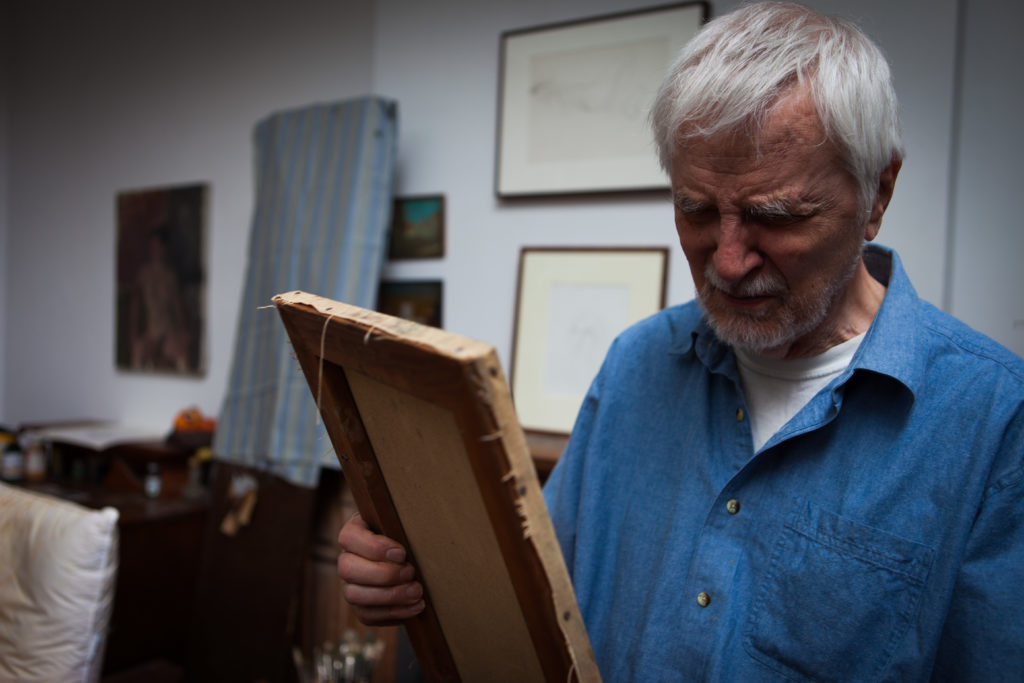

Early after the inception of the Vision & Art Project, Anderson welcomed us into his studio on many occasions. Though our efforts at the V&AP were new and untested, he trusted us to do an oral history with him and to make him the subject of our first film. We cherish the opportunity to have come to know him and to have our eyes opened to “the blessing of light” (as he called it).

“Everything in shambles”

One afternoon in the late 1990s the esteemed realist painter Lennart Anderson, who passed away five years ago at the age of 87, closed his left eye and gazed at the mantelpiece over the fireplace in his Brooklyn studio. What he saw shocked him: “everything in shambles”. Instead of the mantelpiece and moldings traversing the wall in familiar, crisp, horizontal and vertical lines, they were collapsing toward his focal point. His ophthalmologist told him his mantelpiece had served as a test for macular degeneration. The disease had destroyed portions of his right retina. Hence, the distortions. Like many people before him, he learned that his left eye was likely to succumb, as well.

For a few years after Anderson’s right eye “went,” as he would say, he saw well enough to carry on with little change to his working life. In his early seventies then, Anderson was still teaching in Brooklyn College’s MFA program. He was regularly painting for shows that would sell out at his Upper East Side gallery, Salander–O’Reilly. He taught a figure drawing class on Saturdays, where, in between critiquing his students, he would join them in drawing the model. The rest of the week, he worked in his studio.

Monocular vision

As he had done throughout his painting career—albeit now relying on monocular vision—Anderson continued working from life. His ease of transition is somewhat unusual. When someone who has relied on binocular vision loses sight in one eye, it typically interferes with hand-eye coordination and depth perception.

Because our eyes are positioned on either side of our head, we receive two different images when we view a scene. The differences between these images, known as binocular disparity, allow us to calculate depth. This is only one of the many strategies we use to determine where things are in space.

Most people adjust to monocular vision within a year. They learn to rely more on visual cues and head movements to judge distances. But those whose jobs require close work and “prolonged visual vigilance” sometimes cannot perform the tasks they once did. It can prove insurmountable, for instance, for a seamstress to thread a needle. Or for a surgeon to advance scissors toward a suture. Or for a meticulous artist like Anderson to place a fully charged brush where it’s intended to go. Yet after all but losing his right eye, the only effect Anderson noticed is that he had a harder time discriminating color. But not much.

He speculated that it wasn’t as challenging for him as it can for others because his left eye had always been dominant. So dominant that he had always almost entirely closed his right eye when painting, gleaning from it no more than a more nuanced sense of color. Like Anderson, most of us do have a dominant eye, meaning we seek one eye’s input more than the other’s. But, given that he didn’t realize the sight in his right eye had declined, his brain must have all but neglected input from his right eye. Another way of saying that is that he must have had unusually strong left eye dominance.

Luminous landscapes

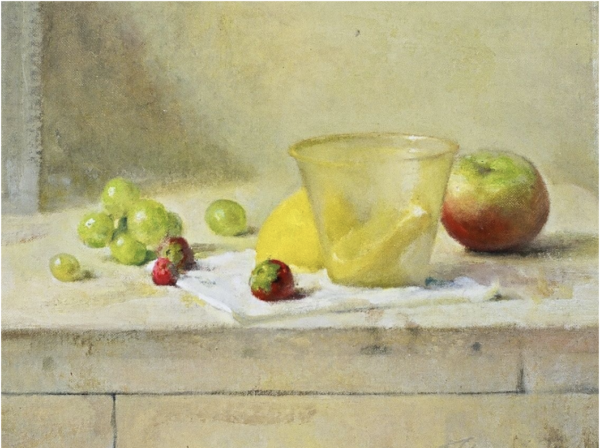

Between 1999 and 2003, Anderson painted with his left eye exclusively. His work lost none of the luminous “sacramental” unity that the critic Ken Johnson said Anderson’s “best” still lifes had. Anderson’s 2001 Plastic Cup with Lemons, Strawberries and Grapes, for example, at first glance an undifferentiated burst of light, owes its radiance to the subtle and fluctuating tonal shifts of light pulsing across a subject — an extraordinary achievement.

Anderson considered Salami on Red Plastic Dish his “last serious still life before his vision went altogether”. Though rendered in darker hues than Plastic Cup with Lemons, the two paintings share a sensibility of vision. Colors shift, sometimes imperceptibly so, encouraging the viewer’s eye to travel along an unbroken visual experience, inhabiting nooks and crannies along the way. What is not apparent from reproductions is Anderson’s sensitive, highly descriptive brushstrokes.

Anderson seemed unsurprised that he was still able to paint so masterfully at that point. “My left eye had always been my real working eye,” he said, “and it was good. Or good enough, you know.”

Anderson’s second eye “goes”

In the summer of 2003, Anderson was painting in his studio in Maine. One minute, everything was as it should be. The next, he couldn’t make sense of what he saw. A gray spot intruded between him and whatever object he focused on. When he did see something, it didn’t look—or feel—as solid as before. The cottage’s wood-slatted wall paneling was askew, ceiling timbers bulged. His ophthalmologist told him that his second eye had been gradually deteriorating. But Anderson felt he went from having perfectly sound monocular vision to being legally blind within seconds.

His friend, the painter Tom Cornell, drove him to an eye doctor in Portland, Maine, who referred him to a retinal specialist in Boston. The specialist told Anderson what he already suspected. His left eye had succeeded the right and succumbed to macular degeneration. But even though the same disease had struck both eyes, it had not done so in the same way. The vision in his right eye was scrambled, but it wasn’t impacted by a scotoma. In contrast, the vision in his left eye was occluded by macular degeneration’s characteristic blind spot.

On the way into Boston to consult the specialist, Anderson thought the city looked like a John Marin painting. He eventually stopped seeing cities tilting in disorienting ways. But he felt that was because his brain started ignoring or correcting his eyes’ flawed impressions. Probably so, given the brain’s role in perception.

The eye-brain interplay

The eye-brain interplay is so complex that it’s not yet fully understood to what degree the camera-like human eye, rather than the thinking brain, is responsible for what we observe. Many of us remember our surprise at learning that the brain inverts the upside-down images formed on our retinas, so that we read them as right-side-up. This is only one of the brain’s many feats of “vision.”

As mentioned earlier, the brain also takes binocular vision’s two separate images and fuses them into one. As our eyes sweep across the line of sight, we essentially take “screen shots” of the focus of our central vision, out of which our brain creates a composite. The brain interpolates and fills in information we cannot see at our physiological blind spot, a place in our visual field where the optic nerve passes through the optic disc of our retina, obscuring sight. For some people with macular degeneration, the brain replaces missing perceptions with images of what might rightly be expected. It can also generate complex visual hallucinations, a condition known as Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS).

Life was radically different

Anderson packed up in Maine and returned to New York City. Summer was almost over, and he always returned to Park Slope then. In time for the fall semester.

Life was radically different than before. Even before his eyesight had failed that summer, he had lost his wife of fifteen years to lymphoma less than a year before. Salander–O’Reilly Galleries, which had been representing him for several years, was closing. And, after thirty years of service, he was retiring from Brooklyn College. In a lecture he’d given at Skowhegan in the 1960s, Anderson had said he rarely had a bad year. 2003 was a terrible one.

“When I’m looking at you, you’re just a blur”

Once his second eye declined so precipitously, Anderson had a hard time articulating what he saw. From a medical point of view, he was “legally blind”. To be legally blind is an ambiguous condition, though. In North America and Europe, it means your visual acuity is 20/200 or less in the better eye with the best correction possible. Which means a legally blind person has to stand twenty feet from an object to see it (with corrective lenses) with the same degree of acuity as a normally sighted person could from two hundred feet.

The world was fragmented. It was also grayer and blurrier than the sharp, colorful, detailed world he used to see. Also, because of the blind spot in his left eye, he now had to rely on his right eye. Referring to his left eye, Anderson said he thought there was “some better sight around in there.”

But it’s not anything I can make use of. You’re trying to get something, it doesn’t work. It just doesn’t work. Right now, when I’m looking at you, you’re just a blur. You’re not even a blur. You’re just kind of a gray spot, but then I get you. That blind spot causes lots of problems because you don’t know when you’re trying to look through it, and you can miss something that you’re trying to find because it’s in the blind spot. I can’t paint like that.

Trying to figure out what to do

Anderson went up to his third-floor studio most days—“to figure out what I could do, you know,” he said. A palimpsest of objects had accumulated there over the years—the tools and materials of his trade, books, CDs, exhibition catalogs, postcards, drawings his children did when they were young, Polaroids of his wife that he used for his ongoing work on his Idyll painting. To these he added a magnifying machine, desktop and handheld magnifying glasses, rulers.

Determination and skill

In his quest to continue painting, Anderson showed a character-defining determination. The same determination that had caused him to remain in New York as a young artist rather than return to Detroit with his friend, the artist Richard Serrin, when it became obvious that it was going to be hard to make a go of it. That had caused him to keep painting from perception, even in the 1950s when he was living on Tenth Street and surrounded by abstract expressionists. The determination that had led him to apply for the Rome Prize three times before finally being awarded the fellowship in 1958. And to work for thirty years on a series of wall-size multi-figure compositions.

But he had more than determination. He also had the insight and skill he’d gained over six decades of painting and teaching. He knew what to look for when painting from life, which is not as obvious as it may seem. It requires its own kind of determination and skill, tempered by judgment and the courage to reaffirm and renew a visual reality. As a result of years of working, he’d developed a dexterous hand-mind-eye coordination, an embodied memory of the gestures and shapes of light and form. Further, like most painters, Anderson wasn’t finished with his life work. Honing that which was yet full of promise remained his métier.

Still, after months of working in his studio, he made no visible progress on a new body of work.

Painting’s new challenges

When he returned to Maine the year after his left eye failed, he took a plastic lion’s mask with him. “It’s really nice to know what you’re going to do instead of worrying about finding a subject,” he explained. He set it up in his studio, along with an artichoke.

To account for his diminished sight, Anderson put his easel closer to his subject than he had in the past. In spite of being just a few feet away, however, Anderson couldn’t see his setup. Or not well enough to paint its north-lit subtleties from life.

Anderson adjusted to being legally blind and managed the daily tasks of living fairly well. But this competency hadn’t transferred over to painting. Among the many challenges Anderson faced, he couldn’t apprehend his entire subject matter in a single glance. At best, he saw fragments coming in and out of focus, or partially effaced by his blind spot. By walking up to a subject and getting his eyes very close to it, he could see fragments well (or well enough) but would lose the sense of wholeness and context inside of which the details fit. Between his non-dominant right eye, with its unstable vision, and his left eye with its blind spot, when his body or glance shifted, what he saw would sometimes disappear.

Though he had achieved renown as a still life painter, Anderson had never painted still lifes exclusively. And though he is generally considered a contemporary realist painter (he is interchangeably referred to as a realist and as a perceptual painter), he never worked exclusively from life. His multi-figure compositions and street scenes were often executed from a combination of imagination and observation. When his second eye succumbed to macular degeneration, however, he was focused largely on painting still lifes from direct observation. If a still life failed to cohere, he adjusted his setup (rather than take liberties with the painting). Given his commitment to perception when painting still lifes, Anderson’s lack of visual acuity was a problem. He couldn’t “feel” his paintings out, as some artists with macular degeneration do. He didn’t work expressionistically.

Relentless effort

Friends who had watched Anderson work recall his relentless effort, even before his vision went, to both accurately perceive and accurately represent the visual field. Millimeter by millimeter, brushstroke by brushstroke, he worked to assess what he saw. A rigorous inquiry into the appearance of perceived reality dominated his process. Was any one point on the subject higher, lower, darker, lighter, redder, greener, etc. than another? When he made a mark, did it truly describe how things looked? Should the note he made be higher, lower, darker, lighter, redder, greener?

This effort to perceive accurately dominated not only the process by which he reached his finished work. Often, it was also what he talked about when the subject of his painting came up.

Through trial and error, Anderson discovered that taking photographs of his setup helped. When drawing photographs up close to his eye, he could see the entirety of a subject as if it were a detail. In other words, a photograph allowed him to perceive the whole subject or whole picture plane up close.

Degas also turned to photographs after his vision deteriorated, though Anderson didn’t arrive at the idea of using them from Degas. Nor did the fact that Degas used photographs make it easier for Anderson to accept his reliance on them. Doing so, he recalled, was “a very difficult decision”. He “hated” the thought of no longer painting his still lifes from direct observation. But, painful and compromised though he felt the effort to by, he completed his first painting since losing sight in his left eye: Lion Mask with Artichoke.

Lion Mask

Back in Brooklyn, he painted the lion mask again. This time he set it up in isolation on a high table. It was just a foot or so from his easel, under the muted illumination of a skylight. It was more or less at eye level and close enough that he could, and would, lean forward to fix a portion of the object within an inch or two of his right eye. This allowed him to focus on and apprehend discrete passages a little better. After viewing his subject up close in this manner, he would turn his attention to his easel, where he’d lean in as close to his canvas as he had the subject, a significant adaptation of how he had once worked. It was customary for him (and most painters) to work more than an arm’s length from his easel.

He would place his fully charged brush on the canvas with an acute lack of confidence. He no longer saw color and was uncertain if his paint mix was accurate or even if he had dipped his brush into the right place. In addition, Anderson had a hard time knowing—right color or not—if his brush stroke had ended up in the right spot. As he worked on one area of the painting, the larger organizational integrity of the painting would sometimes shift. Sometimes without his being aware of it.

For the first time in his career, he needed input, advice, and support when he was in his studio. He sometimes asked his daughter to check his proportions. Some of his former students served as unofficial studio assistants. One, Rita Natarova, worked alongside him on her own paintings and offered help as needed, in particular with proportions.

Blatantly emotional

Lion Mask is one of Anderson’s most blatantly emotional paintings. A hallmark characteristic of Anderson’s approach, from an early street scene of a falling man he painted in graduate school at the Cranbrook Academy, was to paint emotional scenes without emotion. Inspired by Degas, he aspired to take on the perspective of an objective witness. Perhaps such a dispassionate approach was no longer valid or meaningful or possible for Anderson—or so we might surmise from looking at this painting.

Dominated by an up-close view of the subject, the small 12 x 16-inch canvas seems barely able to contain its image. The open mouth of Anderson’s Lion Mask reveals an incisor, dull from wear, useless despite its size. Its face radiates heat, its silvering mane dissolves like ashes into the shadows. Anderson’s perspectival treatment allows us to glimpse but one of the creature’s eyes: the round black hole of the mask, sightless, rimmed in gray. The eye in Lion Mask is like the eyes in the works of other painters struggling to see. We see the same sightless gaze in Degas’s portraits of his blind cousin Estelle. We see it in Titian’s depiction of Marsyas’s glazed sightlessness, which the painter completed when he was struggling to see near the end of his life.

Like one of Gericault’s severed heads

Leigh Morse Fine Arts exhibited Lion Mask in 2008. In a review of the show, Lance Esplund of the Wall Street Journal compared it to one of Gericault’s severed heads.

It is markedly different from any still life Anderson had painted before.

Anderson had typically depicted multiple objects within the context of their larger environment. So placed, the objects in Anderson’s earlier still lifes often seem small, almost diminished. Anderson was not after the objects but rather after light. Anderson’s pre-macular still lifes are subtle. There are moments of striking contrast, such as the highlight on the pewter saltshaker against a dark background. But, generally, no one object asserts its dominance over another. As Wolf Kahn put it in the American Artist, Anderson’s approach to still life painting was a “democratic” one.

What makes Lion Mask powerful is the dominating presence of a single, emotionally laden subject whose symbolic resonance cannot be ignored.

Last still life

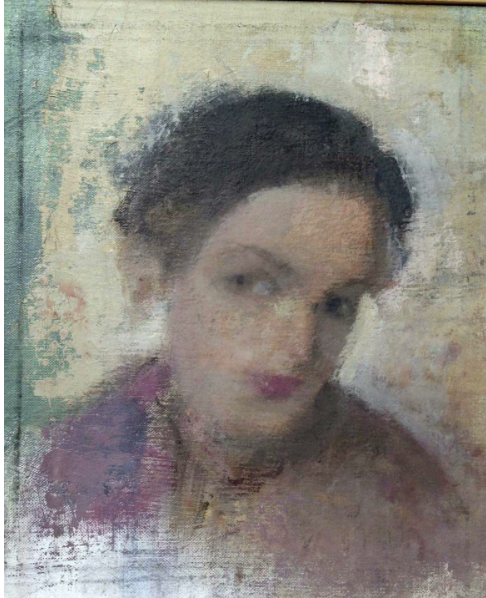

This mask was Anderson’s last still life. In the final decade of his life, he painted the portraits of a few of his friends. He also finished Idyll 3 and used the drawings he had done over his many years as a professor at Brooklyn College to paint figurative works. Many of them were based on antique and mythological motifs.

The mask he used as a model, which he kept on the mantelpiece in his studio, was no more than a hard plastic shell, the kind you might buy at a dollar store. By his own admission, what Anderson had painted was not the object but a self-portrait. Age, futility, and blindness—all are there. So too is mastery, power, and a complex of emotions that give weight—and endurance—to works of art.

Comments

Beautiful article. One correction, my parents were in Rome between 1958 to 1961. Three years at the Academy.

We made a correction. Sorry to have gotten the date wrong. Thank you for letting us know.

Thank you for the fine article about Lennart and his struggle. My wife and I often had encounters with him over the years at exhibitions and other events, often sparring over our contrasting views regarding figurative painting.

As a painter who is also dealing with macular degeneration I was naturally very interested in the article : my left eye being basically non functioning, right eye being sustained, for now, by monthly injections. I, too, at age 88, am continuing in my work, but realize my color and tonal vision is compromised . This has led me do more drawing ( I see line adequately) and mixed media works using only limited color notes. At this point in my career I work mostly from memory and imagination. The prospect of further loss in my”good eye” haunts me. My life, like Lennart’s, has been so bound up in making my art.

Leave a Comment