The Last Free Show On Earth

October 22, 2016

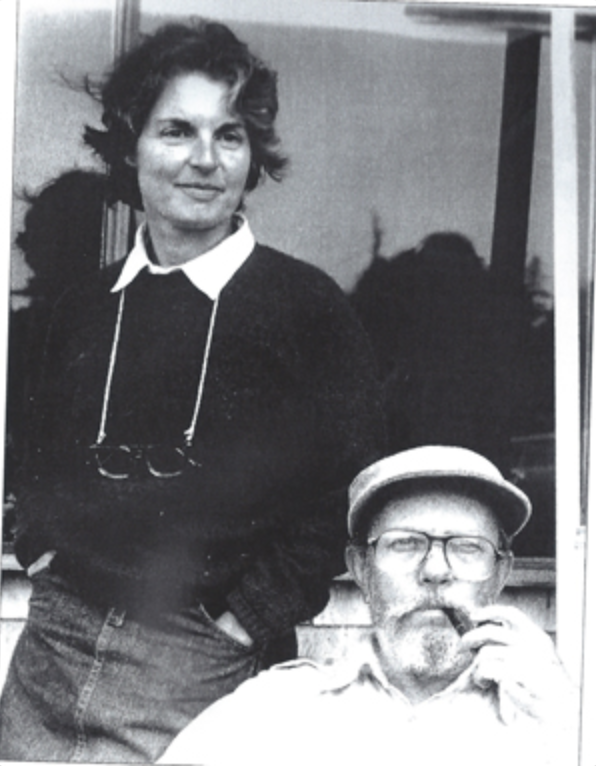

It’s been more than a decade since artist Robert Hamilton passed, but his widow, Nancy Hamilton, continues the tradition of exhibiting his wholly unique work every summer at their property in Port Clyde, Maine.

It started in 1960, what the late artist Robert Hamilton called, “the Last Free Show on Earth”—an annual exhibition of his work in two galleries overlooking the harbor in Port Clyde, Maine. He built the galleries himself, across the street from his garage studio and home, and called them Horse Point Museum in honor of the road by which they were accessed. The show opened every year on the Fourth of July, with the Hamiltons’ annual picnic, which drew scores of artists, friends, family, and students of Hamilton’s from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). It closed at the end of the season—late October, or so—when Port Clyde locals settle in for the winter and its part-time residents and tourists have mostly gone.

Between 1969 and 1986, with the exception of just one show, Hamilton’s work could be seen only at Horse Point Museum, despite its extraordinary artistic and imaginative qualities and a daily work habit that ensured consistent production. He never seemed to have hit a dry spot, not even when struggling with blindness due to macular degeneration near the end of his life. As he explained in a 2001 Maine Masters video portrait, he deliberately turned his back on the art market: “the venality of it, terrible pieces going for enormous amounts of money—I’m getting out. My ambitions were lofty. …” He felt he had to make a choice between aggressively promoting his art or painting every day. He chose the latter.

Maybe this is why Robert Hamilton’s paintings are not better known outside a relatively small circle of admirers, though thanks to his wife Nancy, his work has remained in the public eye and gained slow but steady attention. When Hamilton passed away in 2004, Nancy, who herself has macular degeneration, continued mounting exhibitions every summer at Horse Point Museum, curating shows from the 600 paintings and innumerable drawings Hamilton left behind.

She still lives in the cottage across the street from the galleries and has been known to show her husband’s work in the depths of winter, if she knows you’d like to see it. Along with the exhibits at Horse Point, she was also instrumental in helping to organize a 2011 show of Hamilton’s late, macular paintings at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art (CMCA) and a show at Greenhut Galleries in Portland, Maine (2014).

Happily, Nancy’s efforts have led to Hamilton’s significant legacy now being taken up by others, with his painting Jumping Boy on display at the Portland Museum of Art, a retrospective exhibit at Studio 53 in Boothbay Harbor the summer of 2016, and another show focusing on his work planned at the CMCA.

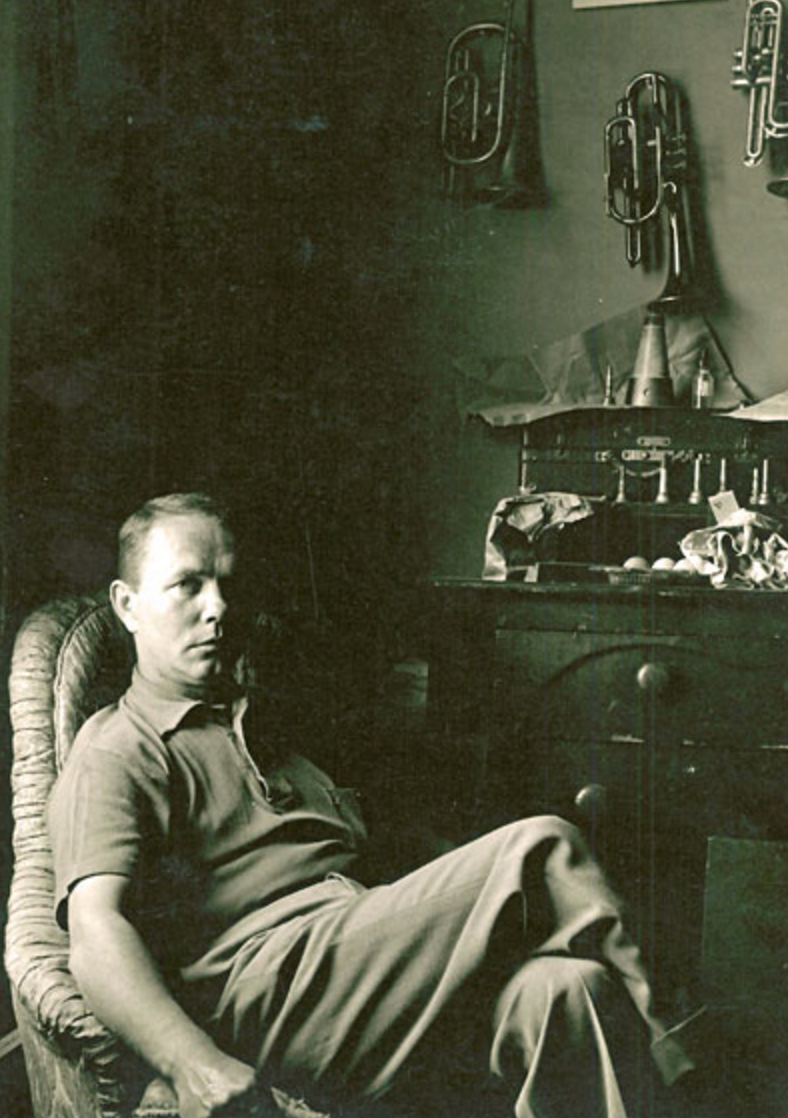

Robert Hamilton’s early art training, career, and service as a P-47 fighter pilot during World War II

Interested in art from an early age, Robert Hamilton entered RISD in 1935. There he met John Robinson Frazier, “one great teacher,” as he said, who taught him that his objectives should be what Thomas Eakins’ had been—a classical approach to art-making that Hamilton never entirely abandoned. As a complement to studio training, Frazier would take his students to Provincetown in the summers, where they worked outdoors and studied Impressionism and Post-impressionism, or, said Hamilton, “what one color could do to another color under a consistent light.”

He left RISD in 1939 (he’d be granted a BFA in 1947) and went to New York, where he took classes for a year at the Art Students League before needing to “face” World War II. He didn’t want to “crawl in the mud,” so he volunteered to be a fighter pilot. He flew 100 missions in a P-47 fighter-bomber, something he rarely discussed except in the most general terms (not even with Nancy), though P-47s would become a fixture in his work: perched on a mausoleum-like building against a vast, green oceanic sky; held in the hands of a childish-looking figure like a toy; a tiny image crossing the mid-point of his drawings like an obsessive, transgressive thought. A few years after the war, he was invited to return to RISD as a teacher and in 1948 began a 34-year career as a professor there.

Creating paintings inspired by jazz

Hamilton liked to say that his artistic vision was born when he was on his way to Providence for his first year of teaching. Though he’d spent his entire life drawing and painting, he’d not yet created a body of professional work or had a show, nor had he given much conscious thought to where he stood at this pivotal point in American art in relation to traditional and more innovative approaches to picture-making embodied by the work of abstract expressionists.

As the train took him toward Providence and his first group of students, he mulled over what he could tell them and use as a guide as an artist. Like so many other artists of the time, he didn’t think the world needed any more Eakins’ and Sargent’s. What emerged in his mind as an alternative was a vague notion of making pictures that would have the “spontaneity and improvisation of Jazz” in them. He’d been “crazy about” jazz from the first time he’d heard it in the ’30s. But how to do that? He didn’t know for sure and eventually discovered the answer by working in his studio: “You think before and after the process of making a painting, but when you are in the middle, you don’t think ‘up front,’ but… use a slice of the brain it’s not easy to get at and that you don’t have control over.”

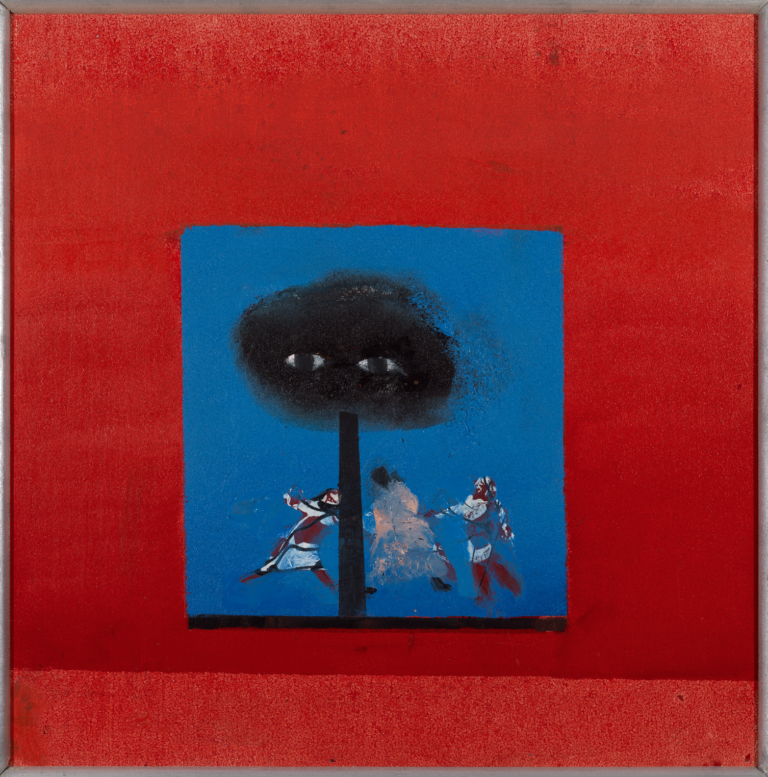

He had little in common with the abstract expressionists, even though they, too, improvised. He was different from them, he said, because he couldn’t let go of certain objectives, like balance of form and negative space, consistent light. He was influenced instead by Francis Bacon, Philip Guston (whom he was personally acquainted with), and Max Beckman, from whom he learned that nothing brings a color to life, makes it so “delicious and juicy,” as a “big whack of black next to it.” Still, he saw his work as markedly different from theirs in that “jokes” started to show up on his canvases. “I don’t know if a joke ever turned up in one of their pictures, but I know that if it did, they’d get it out of there. When jokes started to show up in my canvases, I said to myself, ‘Look, you’re an improviser. You’re supposed to take what comes. If a joke comes, cuddle up to it. Who are you to throw it out?’”

Discovering a unique painting method

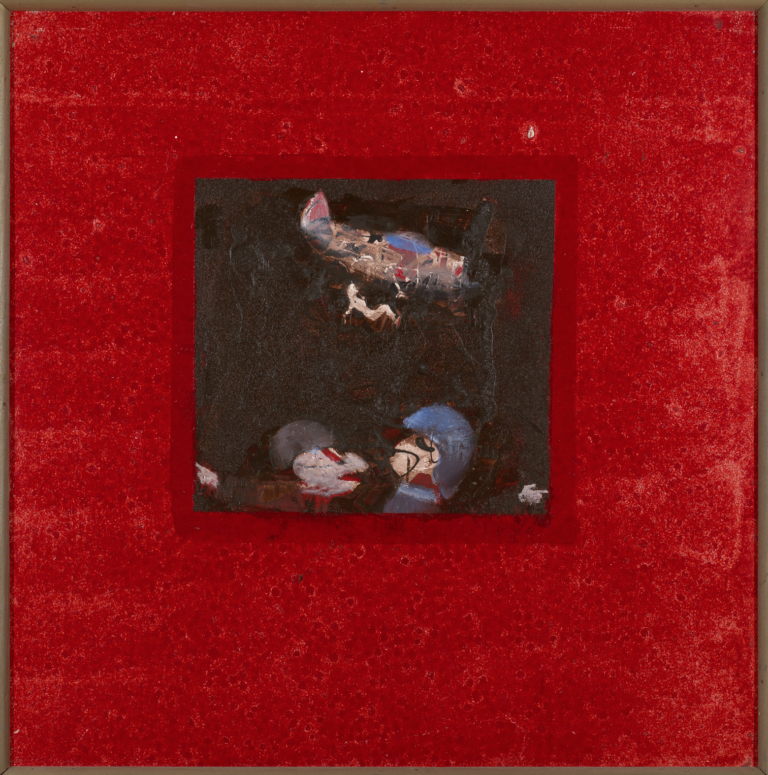

By the late 1950s, Hamilton was beginning to show his work and win awards, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that his distinct style fully emerged, when he discovered a method of working that he would use for the rest of the career. This involved putting down a lot of “exciting abstract expressionist junk” [color, shape and composition] and covering it up with a coat of lamp black. He would then use the palm of his hand to “peel away” the black paint somewhat randomly, thus uncovering what he called “little pictorial events,” “little plays.”

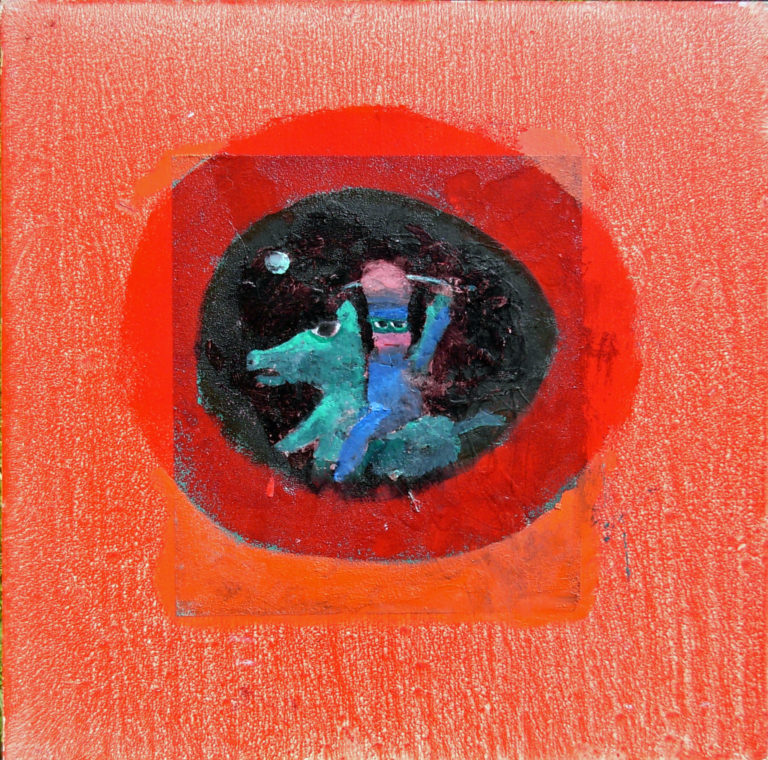

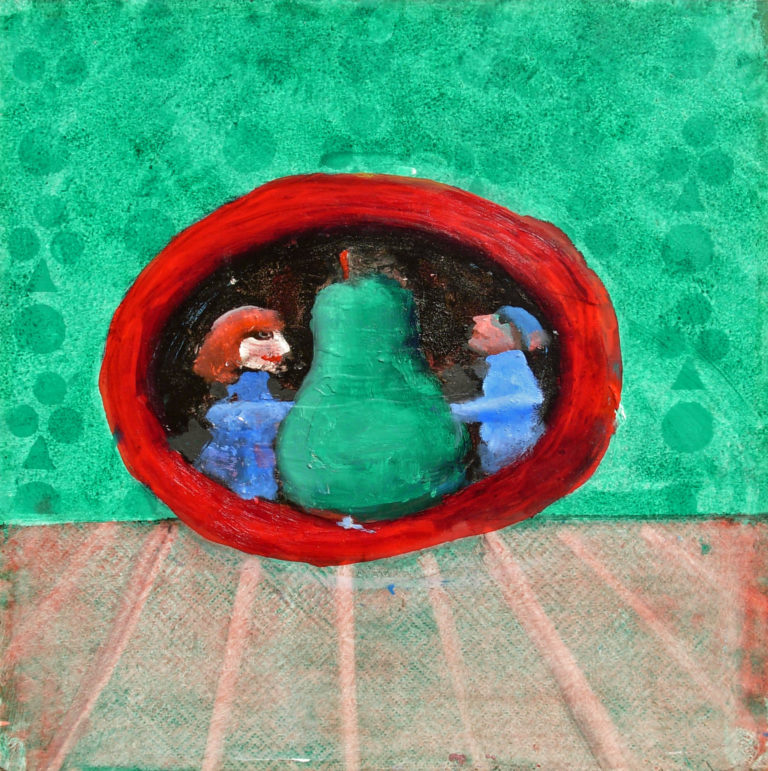

His finished paintings were not completely dependent on chance, however, since he didn’t just allow what he uncovered to stand, but would work into it with his brushes. His system was about inventing a place for something to occur. He emphasized the theater of picture-making by creating stages and populating them with repetitive motifs, hieroglyphic in spirit, that seemed to have haunted and delighted him. Along with B-47 fighter-bombers, the motifs he returned to included images from Egyptian art, trains, moons, mute observers with widely spaced eyes in conductor’s hats and fezzes, performers, and figures in various guises hawking a variety of items—paintings, gigantic pears, memories and dreams.

Late life macular degeneration

Hamilton’s improvisational approach to painting served him well in the last years of his life, when he had no vision in one eye and blurred central vision in the other. He abandoned large canvases and worked instead on 16 x 16 and 24 x 24 inch squares. Paintings more mysterious and chromatic than ever came with the diminishment in size, as if, in shrinking, Robert Hamilton’s vision became fully distilled (a selection of his last works are posted at the end of this article). More vivid and concentrated than what he’d done before, the central images in paintings like Ride a Green Horse, speak of having been drawn from a deep stratum of consciousness. Condensed in the center of the canvas, glowing with significance and beauty, the subjects of these paintings, perfectly clear and utterly elusive, call us toward some distant thing.

In the Maine Masters film interview three years before his death, he has an eyepatch and puffs on a cigar. He’s irascible, defiant, indefatigable, and self-ironic, not least of all when he talks about his vision:

It’s much better to have half of two eyes than full vision in one. If I lose [the] one [I have], I’m in the dark. I don’t know if an hour goes by that I don’t have to think about that. Generally speaking, macular degeneration is an old age disease—the eyes are wearing out. I can see all around, but I can’t see in the middle. It’s a blur in the middle. If you fall off a cliff, you may as well try to fly.* That’s my new motto.

Hamilton’s large paintings in the “octagon”

It’s impossible to write about Robert Hamilton without also writing with admiration of Nancy, who we first met in the fall of 2011 and who has so kindly shared her memories of Hamilton with us. “A’Dora, this is such a small town,” she emailed me in response to my asking her street address when we first went to visit Horse Point Museum.

And in winter it’s empty. You’ll drive down Rt. 131 after you go through Thomaston. It ends at the Atlantic Ocean. Horsepoint Rd. is the 2nd road you come to. The gallery is closed to the public now, but it will be open to you for as long as you can stand the cold. It will be my pleasure to meet you. Nancy.

What we discover at Horse Point every time we visit, including, most recently, the summer of 2015, are idiosyncratic conjurings, spellbinding illusions, hypnotic juxtapositions. Certainly the physical setting of the work contributes to the enchantment. The two galleries Hamilton built are on a great field overlooking Penobscot Bay, and one of the galleries is shaped like an octagon—inspired, Nancy said, by the studio of the Italian sculptor Giacomo Manzù, which she and Hamilton had visited outside Rome and whose “temple-like” mien they sought to capture in the octagon.

But more than anything, the enchantment derives from Hamilton’s work itself. On the eight walls of the octagon, under timber-frame vaulting and skylights, eight large thematically linked paintings (about 80 x 96 inches) are always hung. When we visited in the summer of 2015, these comprised Hamilton’s pictures of train cars. Each painting was divided into multiple frames, where the heads of passengers, looking out the windows of their compartments, were rendered in simple geometric lines, some with high, widely spaced eyes and a line to represent a mouth, some merely a blur of shape.

Nancy explained that when Hamilton was growing up, he’d loved seeing people at train windows as they passed through his hometown of Seneca Falls on the way to Manhattan. These paintings don’t evoke a particular time and place, however. Instead, the faces pressed up against the train windows in Hamilton’s paintings are more archetypal in spirit, heads that look back at us as we look at them, like mesmerists seeking to catch our eyes and cast a spell.

The dreamlike world evoked by the surprising details in Hamilton’s paintings

A dizzying number of details are buried within the simple and broadly articulated shapes of Hamilton’s work, details so subtly inscribed they’re hard to see at first glance. If you look closely at his paintings of train cars, you begin to notice such things as the barely discernible lettering “NYC RR,” the presence of a tiny moon, and a minute attention to ornamental design in the passengers’ dress. These details hint at being significant, yet it’s hard to draw any definite conclusions as to what they might mean. Some expressions and gestures suggest distress; others (like a cat at one of the train windows) promote a sense of the absurd. The seemingly coded messages and exuberant fancies and fantasies within Hamilton’s paintings, which he described as coming from a different, more unconscious “slice” of the mind, tug at the same part of the viewers’ mind.

A second gallery is reserved for the display of a rotating selection of Hamilton’s smaller works. As with Hamilton’s paintings of train cars, patient observation reveals a rich layering of resonant detail in these small canvases, as well. In a tableau dominated by five large red-hatted figures, for instance, a tiny life-like portrait of Hamilton’s daughter is rendered in a visual language that doesn’t appear elsewhere in the picture and thus causes her likeness to become the subject of the work—or, at the very least, the discovery of her image to become the subject of the work. In another, a dark cat emerges from the darkness above an illuminated pink structure, but because the cat and background are so close in tone, the cat could very easily go completely unnoticed.

A late-life artistic manifesto

At some point near the end of his life, reflecting back on his venture at Horse Point, Robert Hamilton wrote a manifesto he entitled, “A SUCCINCT SURVEY of a SERIES of $UCCESSFUL SALLIES in SERIOUS AMERICAN PAINTING of the 20th CENTURY .” “I’m OLD,” he starts off saying. “I’ve been a painter my entire life. It hasn’t been easy.” He goes on:

When I was in Art School, we knew what to do. Shading. A light side and a dark side on every pubic hair. Deftly shading a wooden ball and cone to the degree you’d swear you could reach right in the paper and pick them up. It was fun. There were lots of girls. Tuition was $135. Nobody paid it.

After the war, nobody knew what to do. Bohrod and Soyer and Sawyer, Albright, Benton, Curry and Wood, Kunioshi, Carroll, Cantor and Kroll all had had their day. What to do?

After a long diatribe in which he reconstitutes the history of 20th century painting through the lens of his own perspective that it was “CROAKED,” he closes by saying, “I’m going to go right on producing the picture I’m so justly famed for: a row of seagulls lined up on a lobster shack roof tree, pooping.” In its tone, this statement is similar to others Hamilton made about his work—“My fiction now is that I want to be the best totally unknown painter in the world.” But what his words and canvases ultimately tell us is that he expected his artistic legacy to endure and inspire for years to come.

Robert Hamilton talked about his life in an interview for a 2001 Maine Masters video profile about his work and life (www.mainemasters.com), which is where much of our biographical information.

* This quote is from John Sheridan, the lead character in science fiction television seriesBabylon 5: “If you’re falling off a cliff, you might as well try to fly. You have nothing else to lose.”

Comments

You have done it again. You have the ability to get to the very heart of what matters!!

Thank you for writing this illuminating article on Mr. Hamilton’s work. I’m a colector of his work. I only have one as I inherited from my partner three years ago. It’s a work titled Magritte. I also attended RISD so this comes close to my heart. I graduated with a Master of Architecture but I’m now a full time painter artist. It gives me great pleasure and visual encouragement to see Mr. Hamilton’s work everyday. On another note, I come to Maine every year and I would love to visit the studio and perhaps meet his wife Nancy.

Thank you again,

Eduardo Terranova

http://www.eduardoterranova.com

Dear Eduardo,

We have a great appreciation for Mr. Hamilton’s work as well. I’m sorry to have to convey that Nancy passed away some time after the writing of this article. We hope you enjoy perusing the rest of our site, and please let us know if you have any questions.

Take care, and thank you so much for your comment.

Leave a Comment