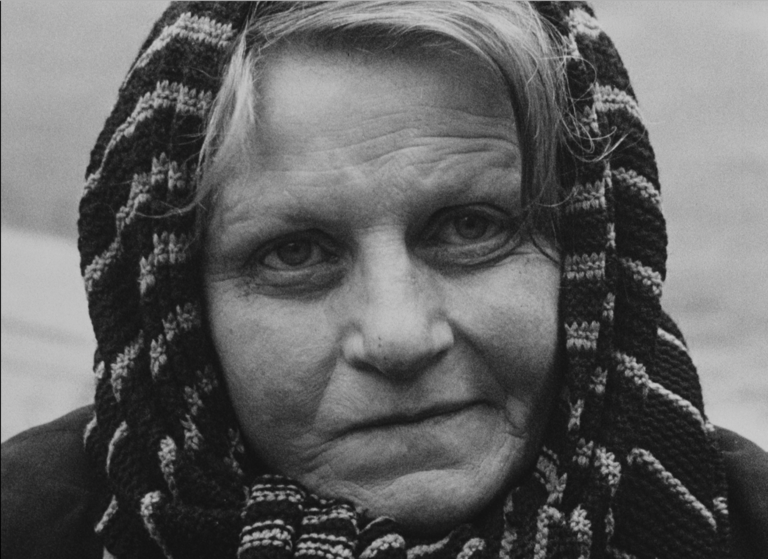

Agnès Varda

1928 - 2019

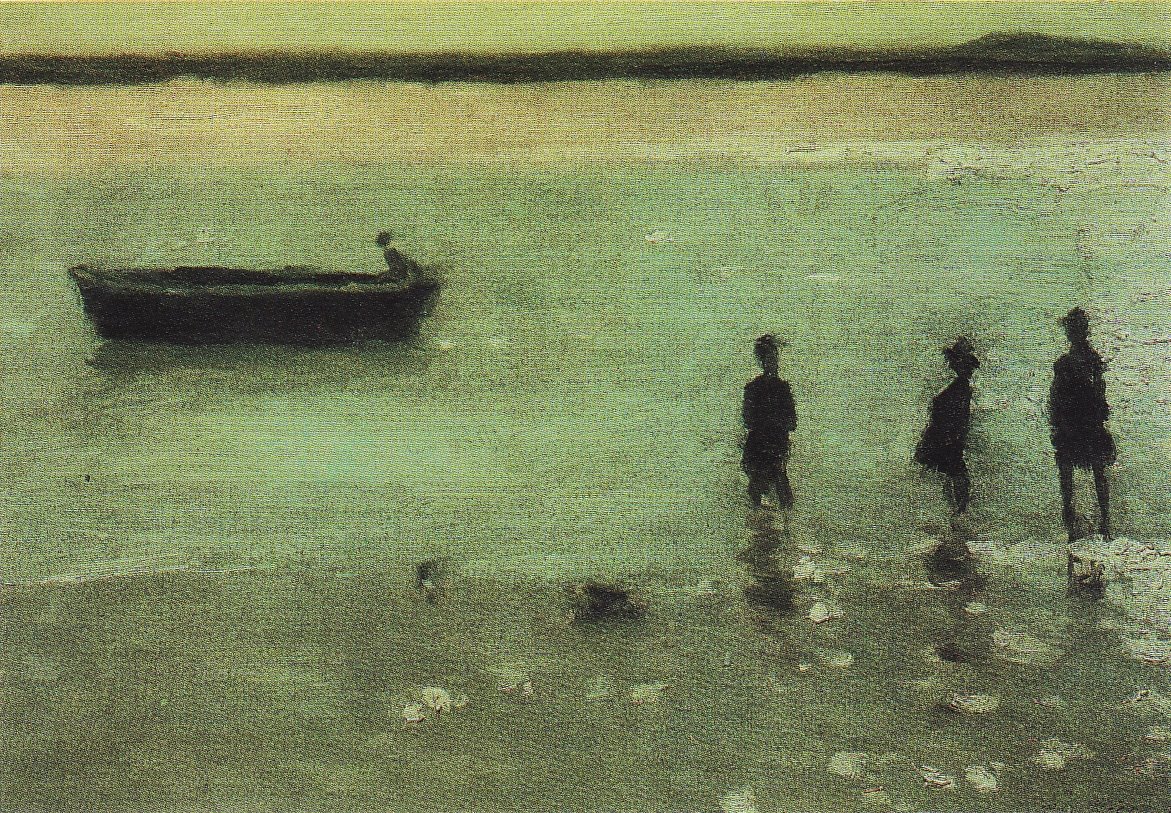

I can’t see them well, they’re far away. But I can see they’re birdwomen.

Agnès Varda in Face Places (co-directed with JR, 2017)

Biography

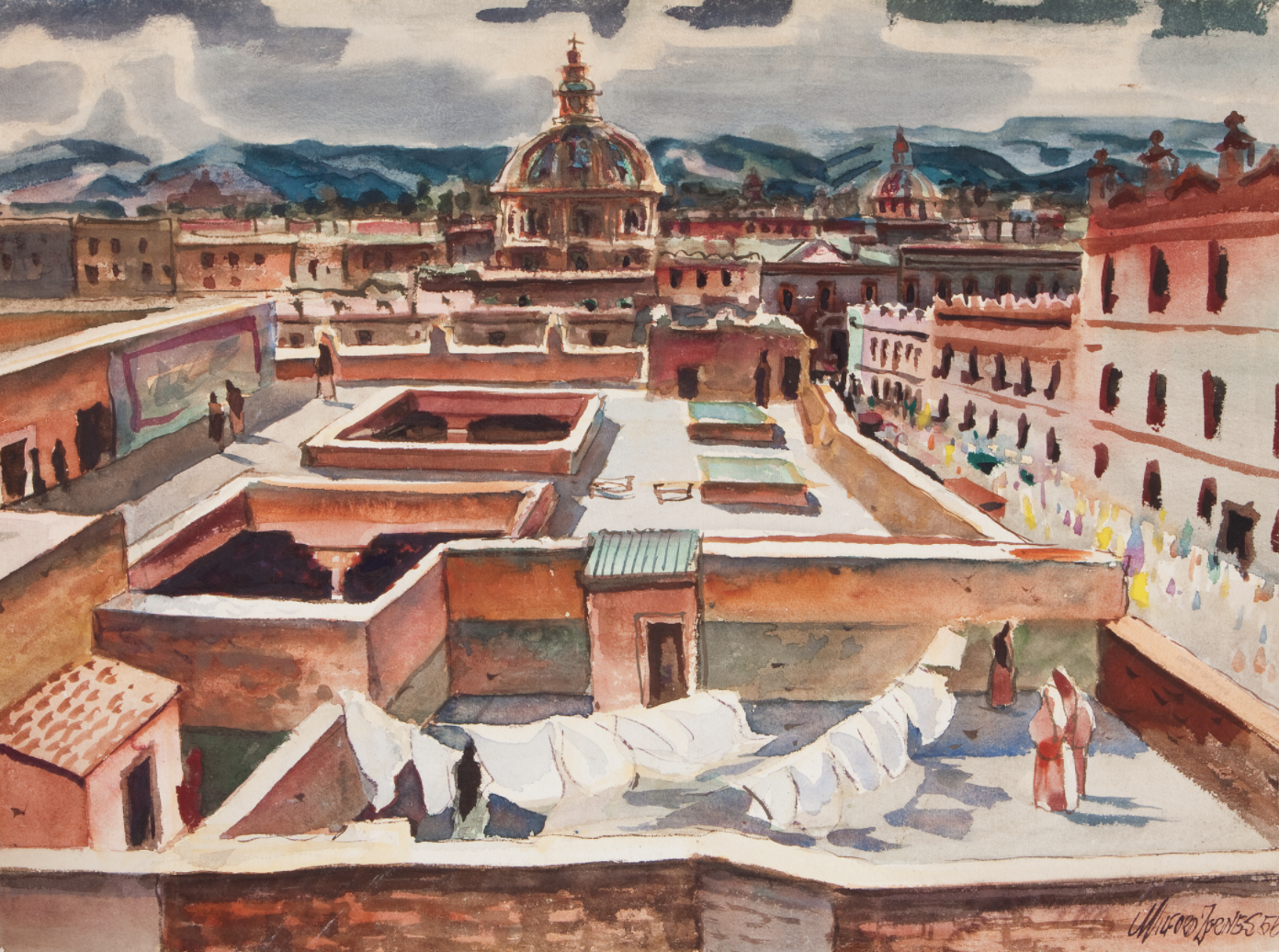

Agnès Varda was a French film director, photographer, and visual artist. She was born Arlette Varda in Belgium to a French mother and a Greek father. Shortly before Brussels surrendered to German forces during World War II (May 28, 1940), she and her family fled to France. At first, they lived on a boat in her mother’s hometown of Sète. Before the war ended, they moved to Paris.

When Varda was 18, she changed her name to Agnès. She received a degree in literature and psychology from the Sorbonne, where she studied with Gaston Bachelard, whose ideas, she says, she didn’t always understand. Intending to become a museum curator, she took classes in art history at the École du Louvre. Yet she was not entirely sure of her way forward. She “ran away” to Corsica without telling anyone.” She spent three months working on fishing boats, during which time she decided to become a photographer.

Early career as a photographer

She enrolled at the Vaugirard School of Photography. Almost immediately, she began to earn a living taking pictures of families and special events. Along with plying her trade as a professional photographer, Varda explored its artistic and creative potential. When her friend Jean Vilar opened Théâtre Nationale Populaire, she became its official photographer. She held this position for 10 years, from 1951 to 1961, during which time she received increasing recognition as a photographer.

As she was building her career as a photographer, she made her first film, La Pointe Courte, in 1955. Then 27, Varda describes writing a script seemingly out of nowhere because she “wanted words”. She’d not seen more than ten films at that point in her life. Nor had she studied filmmaking, or, as was customary, served as an assistant in the industry. Yet, defying all expectation, she shot her first film.

“Godmother” of the French New Wave

This film likewise broke many of the rules and conventions of filmmaking. Its structure, based on that of William Faulkner’s novel The Wild Palms, juxtaposes two story lines. The story lines have nothing in common except that they are set in the same place. The first story is presented by professional actors in a self-consciously theatrical mode. The second story, rooted in real life, is presented by locals with no training in acting.

Thus, three years before what is considered by some to be the first French New Wave film, Claude Chabrol’s Le Beau Serge, Varda created an utterly unique film in La Pointe Courte that exemplified many of the characteristics of New Wave cinema: location shooting, de-emphasized plot, autobiographical inflection, long takes, and a general spirit of experimentation. As a result, Varda is variously called the mother, grandmother, and godmother of the French New Wave.

Over the next 64 years, Varda went on to make many more films. Some were fictions and some were documentaries. However, as in La Pointe Courte, there was always an evocation of the “real” in her fictions and a fanciful element in her nonfictions.

Her works are incredibly diverse in their subject matter and approach. However, throughout her career, she was concerned with the lives of women and the disenfranchised, with time and the cultural moment, and with reality and representation.

Agnès Varda’s macular degeneration and post-macular work

Varda was diagnosed with macular degeneration about 15 years before she passed away in 2019 at the age of 90. Her loss of vision corresponded to what she called her “third life,” when, as she used to say, she “changed from an old filmmaker into a young visual artist.”

Her first exhibition as a late-life visual artist, Patatutopia, was in 2003 at the Venice Biennale. A wrinkled potato, laced with sprouts, seems to breathe at the center of a triptych of similar images. Thousands of potatoes had been poured on the ground in front of the video display. Varda, who saw these heart-shaped potatoes as a talismanic representation of herself, dressed up as a potato to greet visitors to the exhibit.

In the following years, Varda developed 40 exhibitions that often involved “recycling” her former work in startlingly inventive ways.

At the same time, with the help of her daughter, Rosalie Varda, she made a number of critically acclaimed autobiographical films while suffering from vision loss. These included The Beaches of Agnès (2008), Faces Places (co-directed with JR, 2017), and Varda by Agnès (2019).