Agnès Varda’s Third Life as a Visual Artist

July 13, 2021

In the last phase of Agnès Varda’s career, which corresponded with a diagnosis of macular degeneration, she reinvented herself and became a visual artist. She called this her third life (after her first as a photographer and her second as a filmmaker). She liked to say that she was no longer an old filmmaker but was a young visual artist instead. In fact, at the same time as she developed art installations, she continued to make films. We interview Rosalie Varda, who worked closely with her mother in the last years of her life to help her continue creating.

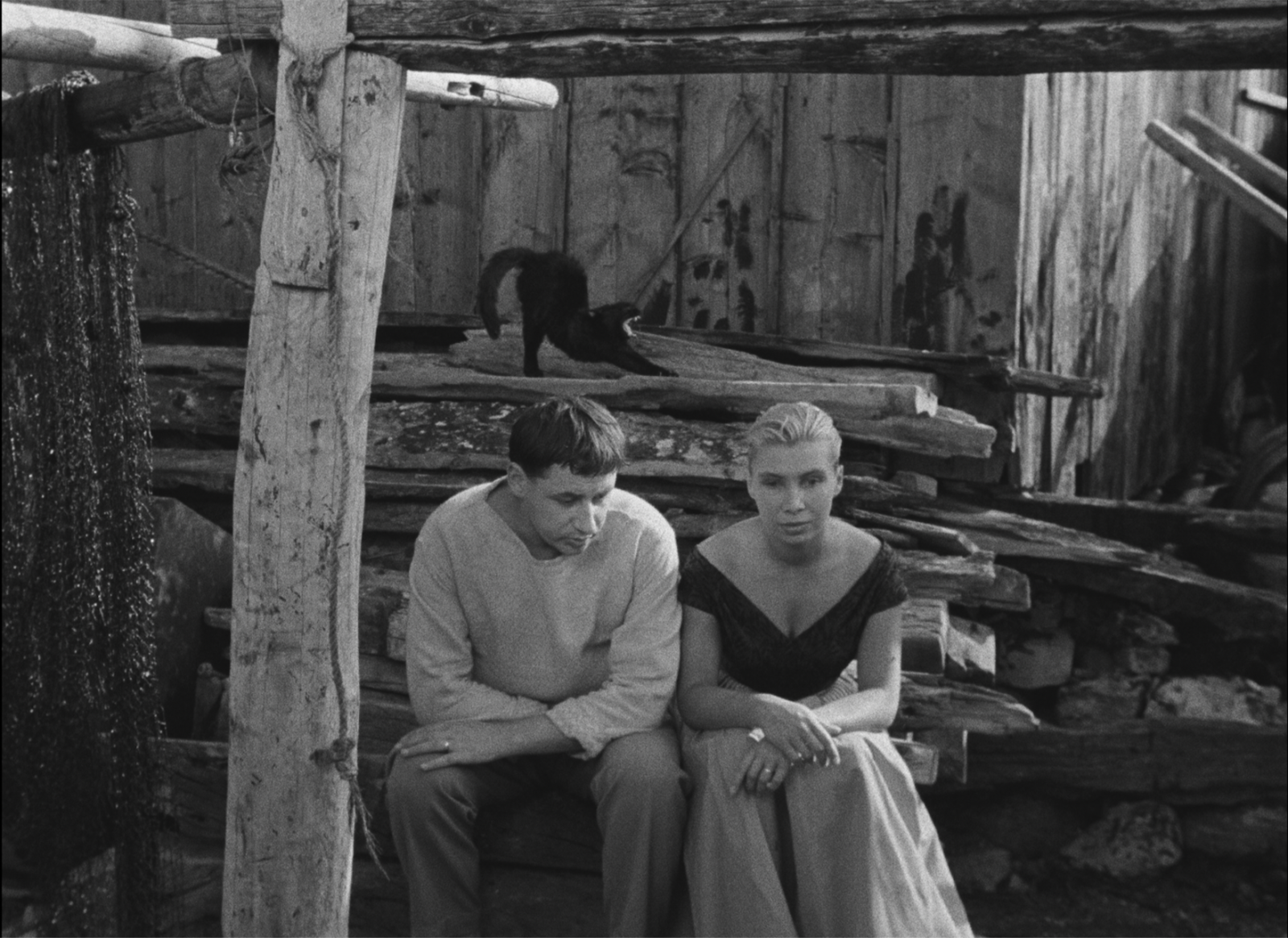

Agnès Varda’s daughter, Rosalie Varda, long collaborated with her mother. At 17, she appeared in Agnès’s film Daguerréotypes (1975), about the shops in their Paris neighborhood along rue Daguerre. Not long afterward, she was in the closing frames of One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977), the story of a friendship between two women set against the backdrop of the women’s movement in France. Later, Rosalie designed costumes for several of Agnès’s films, including Vagabond (1985) and One Hundred and One Nights (1995). When Agnès became a visual artist, Rosalie took on a bigger role. She became her mother’s helpmate, assistant, and collaborative partner.

Patatutopia

Agnès debuted as a visual artist at the 2003 Venice Biennale with a three-screen video installation, Patatutopia. Agnès likened the format to a “triptych.” It featured closeup video shots of blown-up potatoes in different stages of decay. The central image shows a giant heart-shaped potato that has begun to wither and sprout. Agnès first made art out of heart-shaped potatoes in 1953, when she created her photograph Pomme de terre coeur. When she shot her film The Gleaners and I (2000), she was thrilled to rediscover them in a field, cast off as misshapen. She considered them a symbol of her inner self.

In the center panel at the Venice Biennale, she brings the heart-shaped potato to life. It contracts and relaxes, like the heart muscle of any living creature. The background score mimics the sound of respiration.

The left panel shows a video of other blown-up, heart-shaped potatoes. They’re more wrinkled than the one in the center of the installation. Their sprouts, longer, greener, creep down the sides of tubers, an inevitable progression of life and death. The right panel features a video feed of potatoes in a yet more advanced state of growth / rot. Sprouts have turned into long roots that surround the potatoes and seem to draw them into another realm. It is so of the earth, it so strongly evokes death, that it’s somewhat terrifying. Some 1,500 pounds of potatoes lie on the floor in front of the video display. And, in a continuation of the theme, Agnès wore a potato costume to the opening fashioned of resin and wired with speakers.

Making sure “things went smoothly”

After Agnès’s exhibit at the Venice Biennale, the Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art asked Agnès to develop a more extensive exhibition for their Paris gallery. To be invited as an artist fulfilled a youthful dream of Agnès’s. Yet she felt she needed help to carry out her vision. She turned to Rosalie. Thus began a new and more intense period of collaboration between mother and daughter, a collaboration that would continue for the rest of Agnès Varda’s life.

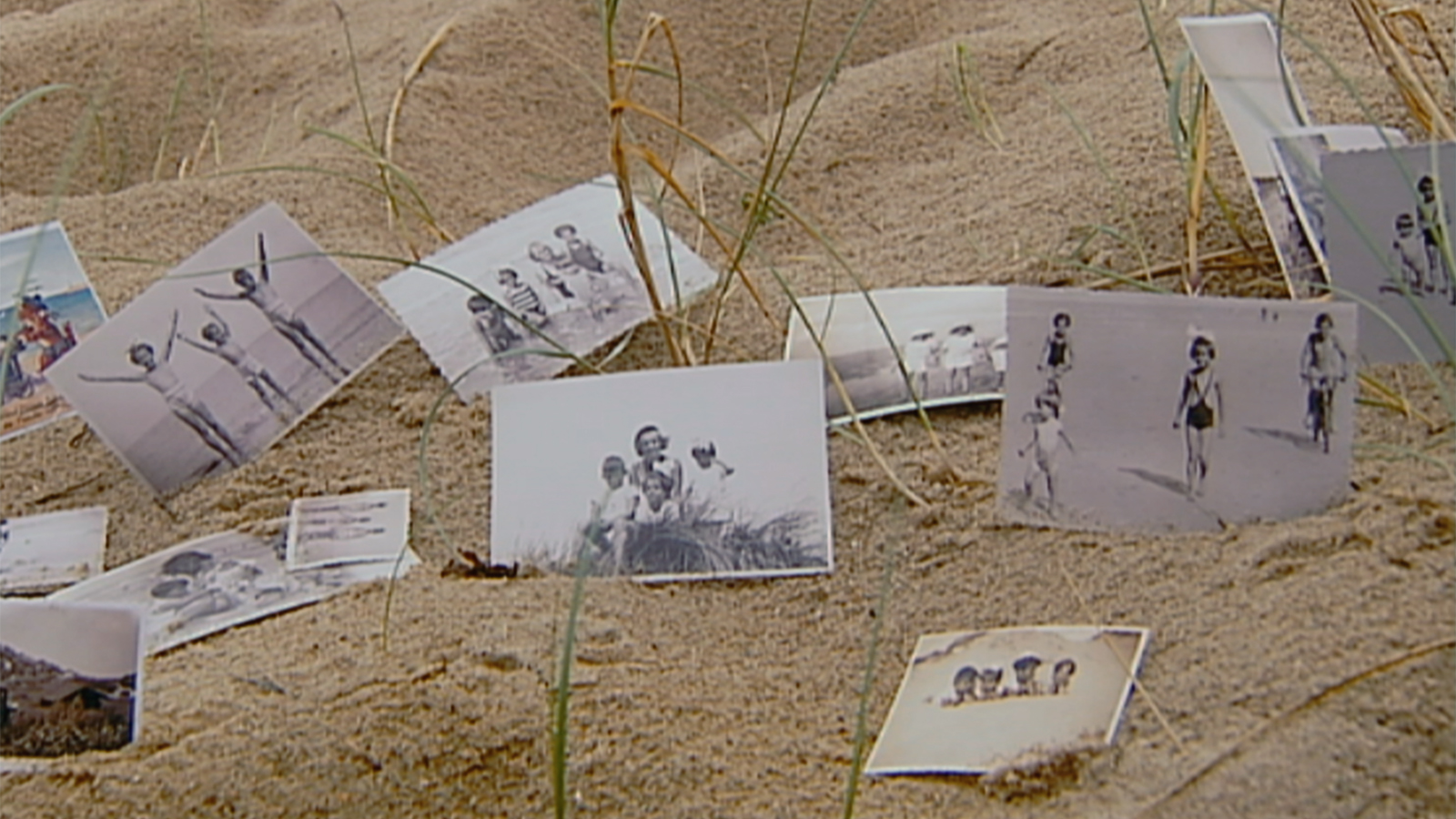

Together, Agnès and Rosalie conceived the show that launched at the Cartier Foundation in 2006. It included several video installations, such as The Widows of Noirmoutier. At the heart of this complex installation are video interviews Agnès conducted with widows young and old from the tidal island where she had a home. Like the women she interviewed, Agnès was a widow, and she included herself as a subject in the installation. Video feeds of women talking about their individual experiences of widowhood surround a central video in which they’ve come together on an Atlantic coast beach. Dressed in black, they ritualistically circle a table that has somewhat improbably been placed at the edge of the sea.

After the exhibition at the Cartier Foundation, Rosalie went on to help Agnès during the shooting and editing of the cinematic memoir The Beaches of Agnès (2008). From then on, Rosalie says, she and Agnès had an “unstated pact”: Agnès still wanted to create; Rosalie would be there to be sure “things went smoothly.”

Rosalie’s role in her mother’s last films

But Rosalie not only helped to facilitate Agnès’s creative vision. She conceived of and produced Faces Places (codirected with JR, 2017) and Varda by Agnès (2019). With Faces Places—a film that is not easily summarized about the friendship between Agnès Varda, “grandmother” of the French New Wave, and JR, a much younger photographer and street artist—Rosalie hoped to bring Agnès’s work to a new generation. Agnès’s declining eyesight and impending mortality become one of the film’s main subjects. Her vulnerability gives the work its gravitas and form.

With Varda by Agnès—Agnès’s autocritical look back on her career—Rosalie wanted to give Agnès a forum to discuss her work before critics, posthumously, began to do so.

In the following interview, Rosalie was kind enough to answer our questions about her mother’s late-life vision loss and extraordinary legacy, as well as the experience of working with her.

Interview: Rosalie Varda

A’Dora Phillips: There are many themes in Visages Villages (Faces Places), and one of them is vision. When did Agnès start having eye trouble and what were her symptoms, how bad was it?

Rosalie Varda: Agnès a commencé à avoir une dégénérescence maculaire il y a une quinzaine d’années. D’abord une fatigue des yeux et ensuite des troubles de la vue. Certains jours elle voyait trouble et des points noirs sont apparus dans son champ de vision.

Agnès’s macular degeneration began about fifteen years before she passed. At first, tired eyes, then trouble seeing. Some days her eyesight was blurry and black dots appeared in her field of vision.

Phillips: Did she go through a grieving process or worry that she might have to stop working?

Varda: Elle a été suivie dans un centre spécialisé pour les maladies oculaires et très vite un protocole a été mis en place pour essayer de réduire la perte de la vue.

She was treated at an eye clinic. Very quickly, a protocol was put in place to try to mitigate any vision loss.

Phillips: What did she have to give up as a result of vision loss? What kinds of adaptations did she make in her life and work (for example, did she co-direct Faces Places in part because of her vision)?

Varda: Elle n’a rien abandonné! Sa vision était fluctuante—certains jours très bien malgré une perte du champ de vision sur les côtés—certains ses yeux étaient fatigués.

She didn’t give up anything! Her vision varied—some days were better although her peripheral vision was not as good—some days her eyes were tired.

Phillips: Did she have to reinvent herself to any degree because of her vision loss?

Varda: Non elle a continué à travailler de la même façon et les équipes autour d’elle l’ont aidée quand sa vision était plus faible. Sa force de caractère et son engagement à terminer ses projets lui ont donné l’énergie nécessaire!

No, she continued to work in the same way. When her vision was weaker, the teams around her helped her. Her strength of character and her commitment to her projects gave her the necessary energy!

Phillips: Throughout her career, the human face fascinated Agnès. By allowing her camera to linger on faces, she gave us some of the most beautiful portraits of the contemporary age. In their empathy and insight, they rival the work of painters like Rembrandt and Velazquez. Most people with macular degeneration struggle to see faces. Did Agnès lose the ability to see faces?

Varda: Elle a continué sans vraiment expliquer ce qu’elle avait vraiment perdu comme vision, certains jours, elle me demandait de vérifier pour elle des tirages de photographies ou des détails dans ses installations… mais je voyais bien que sa vue devenait à la fin de sa vie très faible. Elle s’accommodait comme elle pouvait.

She continued working without really explaining what she had actually lost of her vision. Some days she asked me to check her photographic prints or details in her installations… But I could see that her eyesight was becoming very weak at the end of her life. She dealt with it as best as she could.

Phillips: In her daily life, how did Agnès go about looking and recording what she saw? Did she carry a sketchbook, journal, or camera? Did she sketch, take notes, take pictures? Or did she notice things and rely on memory when she wanted to use what she’d seen in her work?

Varda: Elle notait beaucoup de choses et ensuite je suis devenue un peu ses yeux!

She wrote down a lot of things and then to a small degree I became her eyes!

I think that if we remember one thing about Agnès: it would be her curiosity, which was always positive, and her drive to share emotions and feelings.

ROSALIE VARDA

Mother-daughter collaboration

Phillips: You designed costumes for some of your mother’s earlier films and appeared in Daguerréotypes, then produced Faces Places and Varda par Agnès. At what point did you take on a bigger role at Ciné-Tamaris and what was it like for you to work closely with her?

Varda: J’ai fait les costumes de Vagabond, Jane B par Agnès V et Les Cents et Une nuits—en 2008 j’ai commencé à la seconder dans la société familiale—j’avais envie de passer du temps avec elle et surtout l’aider à faire ses projets artistiques—ses films mais aussi les installations et tout son travail autour de l’image.

I made the costumes for Vagabond, Jane B by Agnès V, and A Hundred and One Nights. In 2008 I started to support her in the family company [Ciné-Tamaris]. I wanted to spend time with her and especially to help her with her artistic projects—her films but also the installations and all her work around images.

Phillips: Are you now the primary person responsible for managing her legacy and Ciné-Tamaris?

Varda: Mon frère Mathieu Demy, acteur et réalisateur, et moi même sommes maintenant responsables du catalogue des films réalisés par Agnès Varda et Jacques Demy. Nous avons aussi toutes les archives photographiques, car Agnès a commencé en étant photographe à partir de 1949.

My brother, the actor and director Mathieu Demy, and I are now responsible for the catalog of films directed by Agnès Varda and Jacques Demy. We also manage the photographic archives, because Agnès started her career as a photographer beginning in 1949.

Phillips: As someone who knows Agnès Varda’s work and life better than anyone, what do you think is the most important thing to understand about her?

Varda: Je crois que si on devait garder une chose d’Agnès: c’est sa curiosité toujours positive et son énergie à partager des émotions et des sentiments.

I think that if we remember one thing about Agnès: it would be her curiosity, which was always positive, and her drive to share emotions and feelings.

Agnès Varda’s transformation into a visual artist

Phillips: Agnès’s move to visual art in 2003 with Patatutopia seems as surprising as her having made her first film, La Pointe Courte, “out of nowhere.” What inspired the new direction?

Varda: C’est Hans Ulrich Obrist qui lui a proposé de créer une installation pour La Biennale de Venise en 2003, et il lui est apparu comme évident qu’elle avait envie de continuer à explorer des images de ses films ou bien d’en inventer. Cette nouvelle aventure dans l’art contemporain qu’elle appelle « sa troisième vie » lui a donné des joies immenses et elle a fait une quarantaine d’expositions en 16 ans.

Hans Ulrich Obrist suggested to her that she create an installation for the Venice Biennale in 2003. It was obvious to her that she wanted to continue exploring images from her films or inventing new ones. This new adventure in contemporary art that she called her “third life” gave her great joy, and she created 40 exhibitions in 16 years.

Early and late Varda

Phillips: In Varda par Agnès, Agnès said that at 80, she panicked, but at 90, she no longer gave a damn. What do you think she meant? No longer gave a damn about what, and how did this influence her work?

Varda: C’est une façon de dire qu’elle avait encore plus de liberté. Après 80 ans quand on est en bonne santé et que l’on peut travailler comme elle 10 heures par jour: c’est du BONUS!

This is a way of saying that she had even more freedom. When you’re 80 and healthy and you can work like her, 10 hours a day: it’s unexpected extra time!

Phillips: I see many images from Agnès’s early films in her late films (for example, gleaners in Documenteur before they appear in Les Glaneurs). I also see many of her late films in her earliest (a sense of opening up a person to find a landscape is in La Pointe Courte long before she made it explicit in Les Plages d’Agnès). What can we understand about your mother’s work only now that her first work and her last have been completed?

Varda: C’est tout l‘intérêt de regarder tous ses films—on trouve des références, des liens qui se tissent ou des morceaux de puzzles qui s’assemblent.

That’s what’s interesting about watching all her movies—you find references, links that are forged or pieces of puzzles that come together.

Art and chance

Phillips: Agnès seems to have felt that viewers should do some “work” to watch her films. For example, the tracking shots in Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) are shot from right to left to create a sense of discomfort. It’s the opposite of how we read in Western culture. Why did Agnès feel it was important to challenge viewers?

Varda: Les spectateurs sont intelligents! À eux de trouver ce qui les intéressent. Les films d’Agnès ne sont pas difficiles.

Viewers are smart! It is up to them to find what interests them. Agnès’s films are not difficult.

Phillips: Agnès was interested in society and invested in trying to make a better world. So I was surprised that she said in a presentation at Harvard in 2018 that she didn’t believe art could change the world. What did she think art was for?

Varda: Je ne suis pas sûre qu’elle ait dit cela? Car l’art ne peut pas changer le monde mais peut aider à mieux le comprendre….

I’m not sure she said that? Because art cannot change the world but can help us to better understand it….

Phillips: Agnès talked often about the role of chance in the making of her films. She said things like, “Chance provided the staging” and that it was “gorgeous when chance fulfilled her expectations.” In Agnès’s opinion, was there anything behind chance—providence, sign of a Maker, luck, the projection of our psyches onto the environment?

Varda: Je crois que les imprévus et le hasard étaient pour elle—son meilleur assistant et elle était toujours capable d’en tirer profit pour son film. Agnès avait cette qualité d’accepter les surprises sur les tournages!

I believe that the unexpected and chance were for her—her best assistant. She was always able to take advantage of it in her films. On set, Agnès had the quality of accepting surprises!

Leave a Comment