Hedda Sterne

1910 - 2011

“First, good news. I made, with a hand held greatest strength magnifying glass, three drawings. I get up at 4, work for 4 or 5 hours and then rest and continue like this.”

Hedda Sterne in a letter dated November 28, 2000 to Claire Nivola

Early background and training

An imposing figure in Twentieth Century American art, Hedda Sterne was born Hedwig Lindenberg to Jewish parents in Bucharest in 1910. By the age of eight, Sterne showed an early interest in drawing. Recognizing her special talent and proclivity, her parents provided her with private art lessons.

Along with art, Sterne was tutored at home in languages and classic literary texts, many of which she read in their original languages. As a young woman, she traveled frequently to Vienna and Paris, where she attended classes at the ateliers of Ferdinand Léger and Andre Lhote. In 1929, she began formal studies in art history and philosophy at the University of Bucharest (she was never to complete them). Her profound early education and cosmopolitan upbringing provided the foundation for a life-long exploration of the arts, literature, and philosophy in her thinking and artmaking.

Sterne’s first international recognition came when Jean Arp praised her collages, which were included in an important 1938 group exhibition in Paris.

Becoming a refugee artist in New York City

Sterne’s emerging art career in Europe was disrupted by the Second World War. So too was the life she’d settled into after marrying her first husband, the Romanian businessman Frederich (Fritz) Stern. Between 1932 (when Sterne married) and 1939, Sterne and her husband lived between Bucharest and Paris. When the Second World War started, Hedda Sterne joined her family in Bucharest; her husband resettled in the United States. After the Bucharest Pogrom (January 1941), Sterne fled to the United States in October 1941. There she met her second husband, the fellow Romanian artist and refugee, Saul Steinberg.

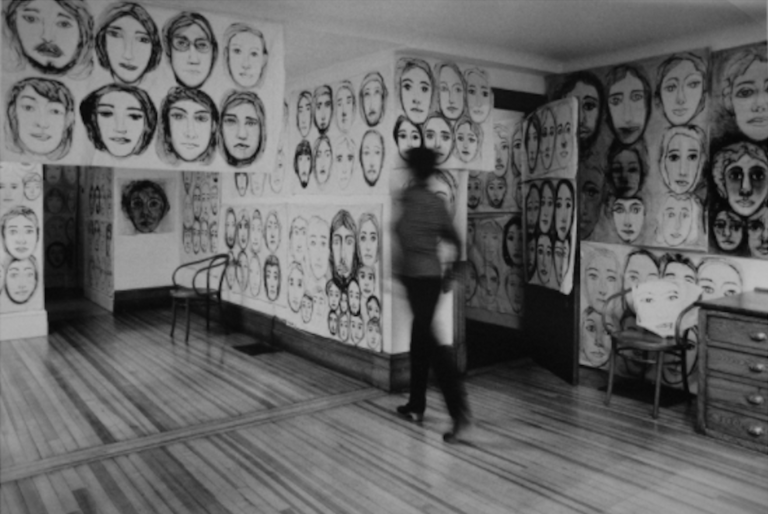

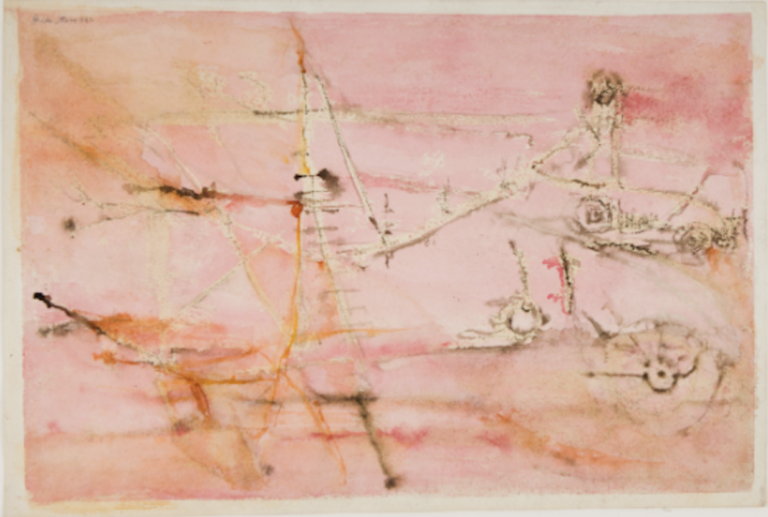

Sterne became involved with the circle of New York School artists with whom she is often associated. In spite of this association, however, she worked with a myriad of materials and styles over the years to create paintings and drawings that often defy categorization. In the 1950s, she used spray paint in abstract paintings of roads, highways and cityscapes. In the 1960s she used oil to create a series of large, vertical horizontal paintings and crayon for a series of drawings that explored more philosophical ideas about visual perception. Along with exploring philosophical and perceptual ideas in her work, she maintained a lifelong interest in portraiture.

Highlights of Sterne’s career

During her distinguished career, Sterne exhibited in dozens of solo and important group exhibitions, including in four decades of shows at Betty Parsons Gallery. Her work was acquired by major museums, such as the Museum of Modern Art, The Whitney Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The sole woman in the famous 1951 Life Magazine photo, “The Irascibles,” she was the subject of two major retrospectives: at the Montclair Art Museum in 1977 and at the Krannert Art Museum (the University of Illinois, Champaign) in 2006.

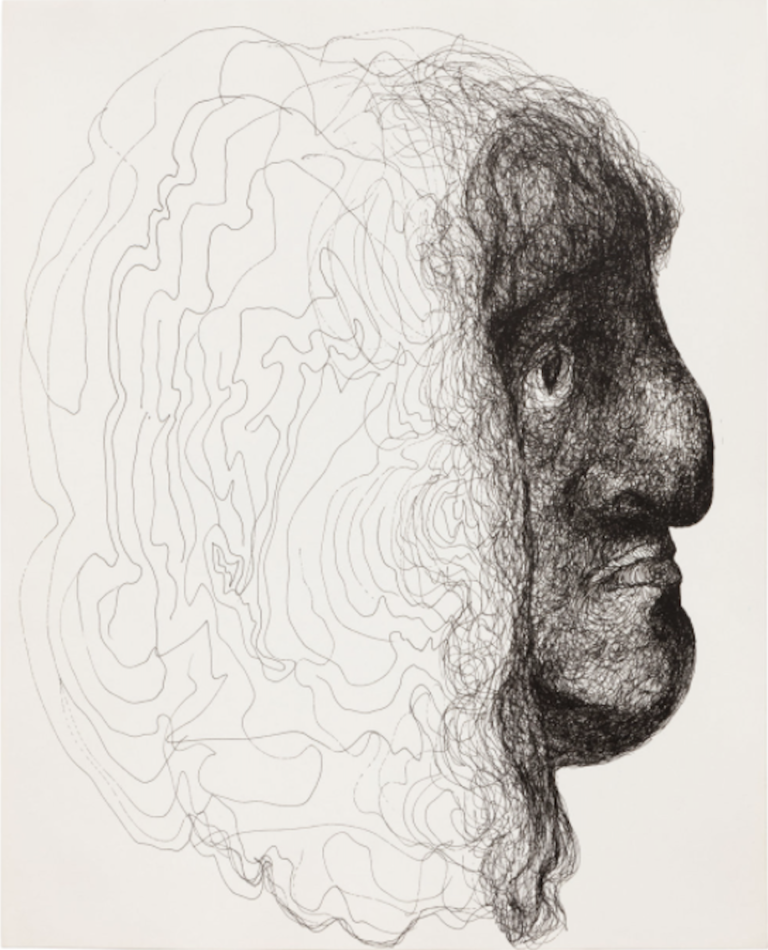

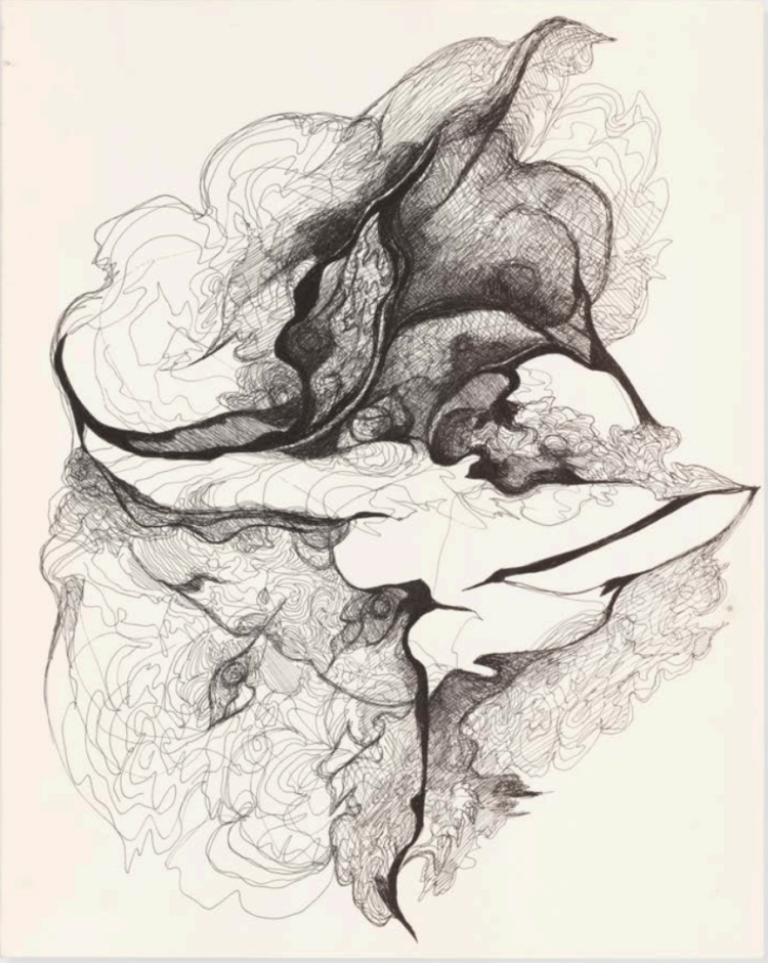

Sterne’s Post-Macular Artwork

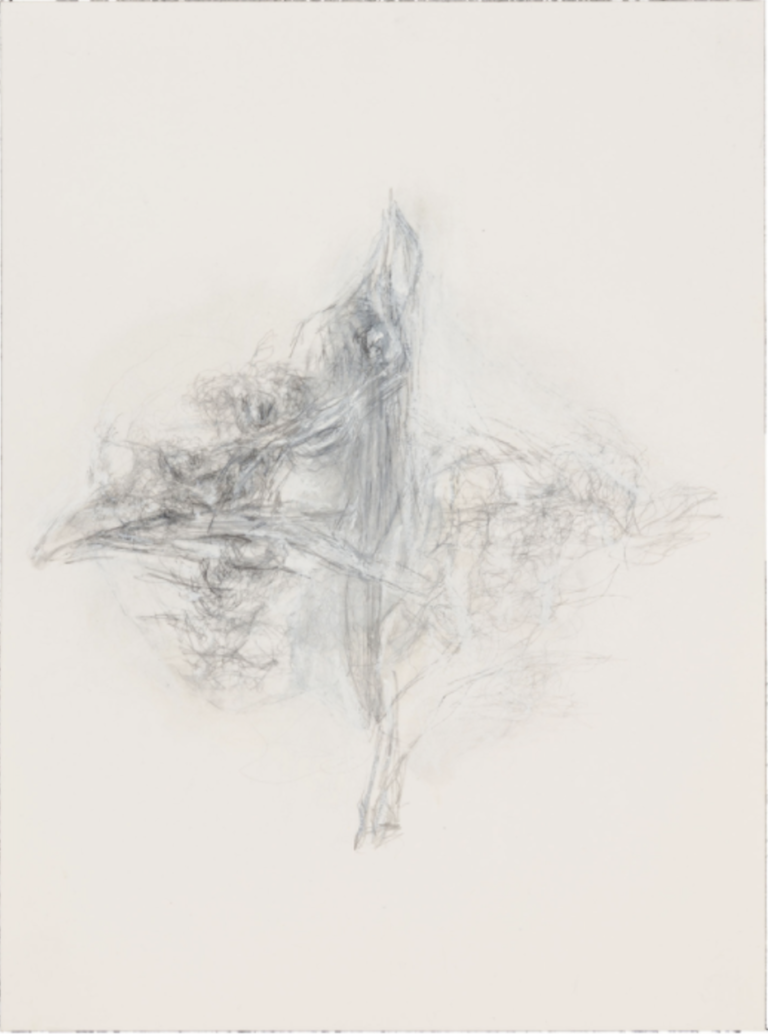

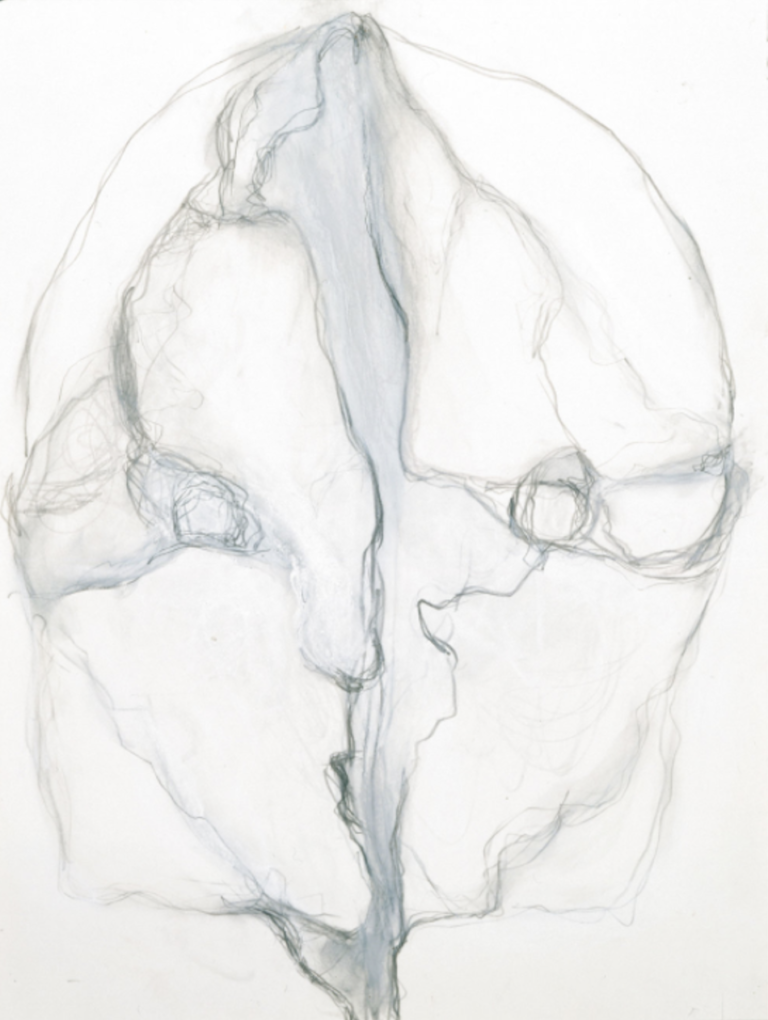

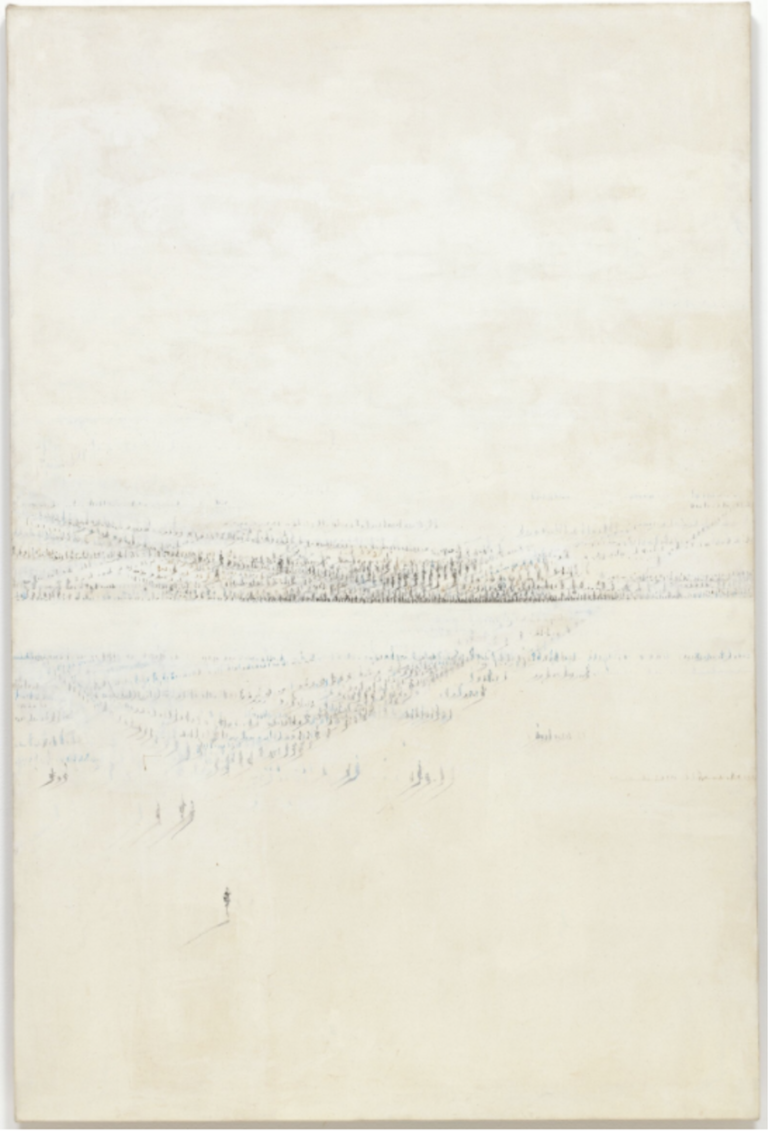

By the time Sterne was 83, her vision was affected by macular degeneration. By the age of 88, she could no longer see well enough to paint and began to draw exclusively. Working monochromatically with such materials as pencil, watercolor, wax crayon, pastels, and white-out on white paper, she often drew egg-shaped masses that can be read as heads and interpretations of subjects from nature such as insects and trees. Some of her last drawings she called “ghosts.”

These late drawings are considered by many to be among her finest works and can be found in several important museums, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Berkeley Art Museum.

Lawrence Rinder, who visited Stene in her studio many times between 2001 and 2004, while he was curator of contemporary art at the Whitney Museum of American Art, describes how these works were made:

She read—and made her art—using a very powerful magnifying glass. I think her sight was very bad and she probably wasn’t even able to see me aside from a general form. She had a table set up in the front room of her house. Her magnifying glass was on the table.

I don’t recall her speaking about [her vision loss] much, but it does seem clear that she had the capacity to continue “seeing” even with low-sightedness. That is, she “saw” things beyond the field of vision, observing fundamental structures and dynamics of being. What is remarkable is that she was able to create images of these “visions.” Her ability to compose images must have come from her memory (perhaps kinesthetic memory) of form.

Sterne stopped working altogether when she was incapacitated by a stroke in 2004. In a 2009 interview, she said that she was still drawing, in her head.

V&AP Resources Related to This Artist

Feature Article

Hedda Sterne’s Recommended Books

Hedda Sterne was a passionate reader. We offer her refreshingly timeless book recommendations as captured in her correspondence with a friend.

Read More

News Forum