From the archives: Oliver Sacks’s Insights on Vision and Blindness

November 14, 2024

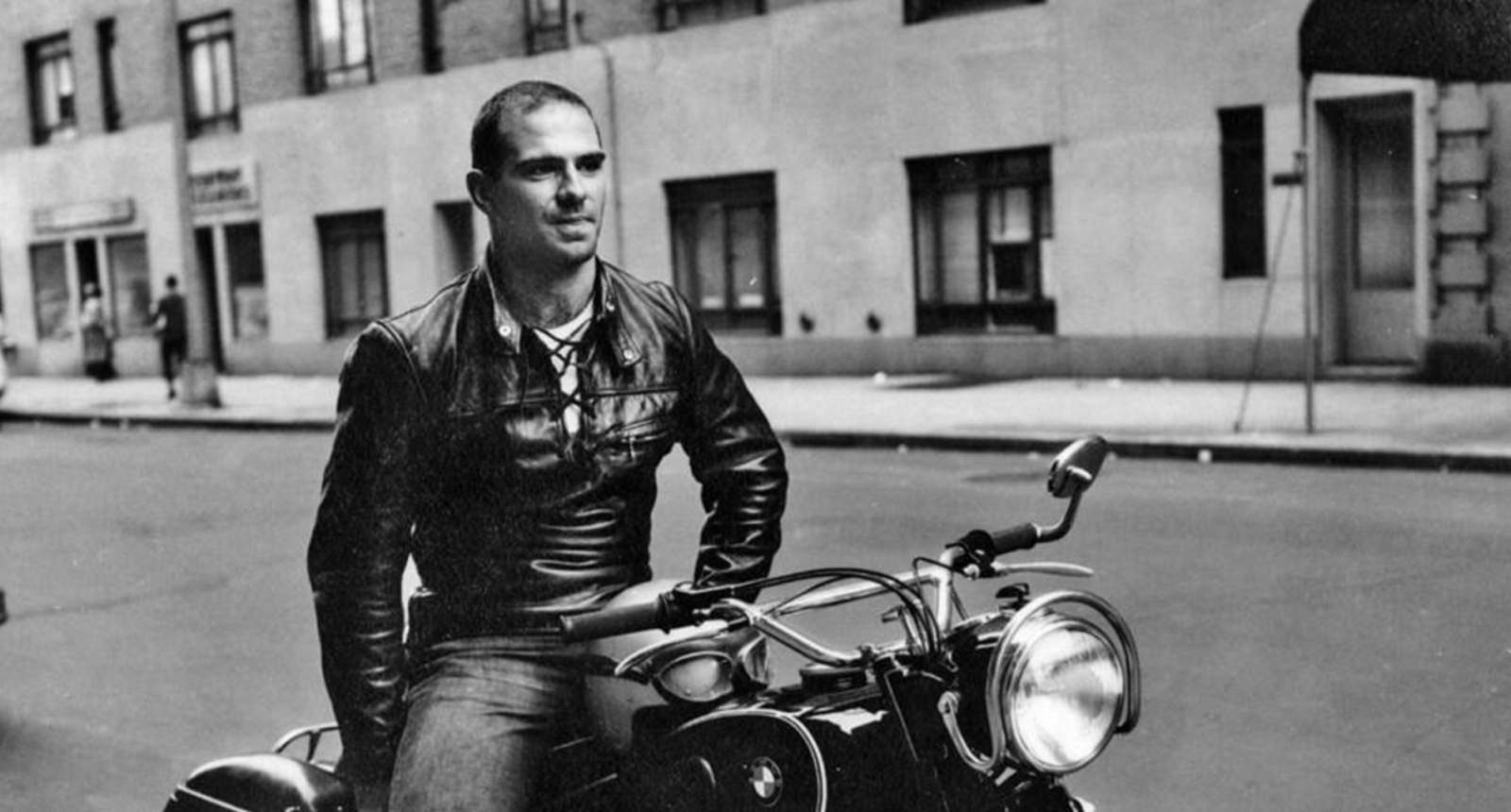

This year, we have been highlighting articles from our archives. With a selection of Oliver Sacks’s letters having recently been published, we have gone back to one of the earliest pieces we ever posted at the Vision & Art Project, on November 25, 2015, to commemorate Oliver Sacks’s passing that year and his last book, which focused on the wonder of the human eye and perception, as well as his own experience of vision loss.

Like so many people who have turned to Oliver Sacks’s writings for pleasure and insight, upon his death this past August we were struck by the profundity of this loss, the flow of ideas we had come to expect from him ended—no new chapter, no new book, no new insight. The unspooling thread of his thought and his life story had not only a beginning now but an end.

Among the many physiological processes to which Sacks brought his formidable intellect was human vision. The title essay in his 1985 book, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, comes from the case study of a man with visual agnosia, a condition in which a person can see but cannot recognize or interpret visual information due to damage in the visual processing structures of the brain. His 1995 book, An Anthropologist on Mars, includes essays about a painter who becomes colorblind after suffering a concussion and a middle-aged man who regains sight after having been blind since early childhood.

Two years later, he followed up with his Island of the Colorblind, which explores total congenital colorblindness among a community of people born on the Micronesian island of Pingelap. Then, in 2010, in the wake of Sacks’s own suffering a partial sight loss, he brought out The Mind’s Eye, a book that focuses on vision’s peculiarities and wonders, how it might be enhanced and the many ways it can be lost.

In The Mind’s Eye, Sacks discusses the role of both the eye and the brain in seeing

Though the range of subjects in The Mind’s Eye is wide, one of the main threads that runs through this book is that vision is dependent on both the eye and the brain. Another main thread is that, in compensating for loss of function, the human mind, ever plastic, “[develops] different patterns, different habits… a different identity.”

Sacks illustrates this perhaps most memorably in his essays on agnosia, like “Sight Reading,” which gives us a riveting portrait of the concert pianist Lillian Kallir. Kallir gradually lost the ability to make sense of the visual world due to a degenerative brain disease. Even though she could “see,” her inability to interpret visual information rendered her essentially blind. She could not read or drive; activities like shopping and walking on a street became fraught with difficulty.

Kallir’s career was of paramount importance to her, a common thread with all of the artists with whom we work, and she adapted her working practices so that she could continue to play the piano. Along with other changes, she began to rely on muscle memory and ear, much as the painter William Thon, when producing his remarkable post-macular paintings, relied on his memory of both the textured swell of a forested landscape, and the visual and physical sensation of a bark on a tree.

Sacks devotes a long chapter to his own loss of vision due to an eye tumor

One of the most powerful pieces among Sacks’s rich and varied writings on vision is a chapter from The Mind’s Eye called “Persistence of Vision: A Journal.” In this chapter, Sacks recounts his own experience of going blind in one eye because of a malignant eye tumor. As a doctor and a writer with a novelist’s sensitivity to detail, and one who himself suffered vision loss, he sheds light on the physical and emotional repercussions of sight loss in ways inaccessible to most of us, even the artists we work with who have macular degeneration.

As Sacks explains, his ordeal started in December 2005 when he was at a movie theater and became aware of a “fluttering, a visual instability” to his left. This fluttering “flared up like a white-hot coal, with spectral colors—turquoise, green, and orange” when the screen went dark after the first preview. After he spent a few minutes testing his vision, he realized this visual disturbance was located in his right eye, but he could only guess at the cause—hemorrhage, blockage of the central retinal artery, retinal detachment?

Sacks is afraid of going blind when he first experiences vision loss

Sacks immediately panicked at the thought that he might be going blind. When he learned he had a malignant tumor, his fear of dying exceeded his fear of blindness (“I have made a bargain with the tumor,” he writes, “you can have the eye, if you insist, so long as you leave the rest of me alone”), but the thought of losing sight continued to terrify him. He gave his dread of blindness, commonly counted as one of the greatest human fears, palpable expression in a number of passages:

I wake from a nightmare. The moment I open my right eye, I perceive something is wrong. The Darkness has inched forward—I can hardly see anything now to the left. I am calm and rational on the surface… but I feel a terrified child, a child screaming for help, inside me.

4 a.m.: Woke. Cold. The Fear. I open my right eye. The Darkness has grown again, is coming to encircle my little island of vision, my fixation point, my fovea. Soon it will be engulfed entirely.

Although Sacks did not have macular degeneration, his vision loss resembled what someone with the disease experience

Sacks’s tumor was located close to the same part of the eye that is compromised by macular degeneration, the fovea—a tiny pit in the center of the retina that is packed with cones and allows us to see clearly. When he closed his good eye, he describes being “startled to see that the horizontal bars on the air conditioner all seemed to be warped, converging and collapsing into one another, while the vertical bars diverged,” a common symptom of macular degeneration.

He found this loss of central vision debilitating:

[M]y vision started to go again—testing my right eye…, I found I could not read even the large headlines of The New York Times. This terrified me, showed me what loss of central vision was like.

Whatever I looked at with my right eye disappeared—the center of my clock disappeared, leaving a halo of peripheral vision around it (I dubbed this in my mind, “bagel vision.”) It gave me a sense of horror. If this were permanent and it affected both eyes, it would be terribly incapacitating—is this what people with macular degeneration have to live with?

So often, by the time we meet artists with macular degeneration, they have begun to come to terms with and adapt to diminished sight, which sometimes masks the emotional and practical challenges of their drastically altered lives. But in talking about the early days of their diagnosis, many of them echo the fear and disorientation Sacks described.

Visual artists often funnel these emotions into paintings that are more overtly expressive of emotion than those they created before. This greater expressiveness is one of the many ways in which the onset of blindness can open up new directions in an artist’s work. The portraits that Edgar Degas painted of his blind cousin, Estelle Musson, when he himself was growing blind come to mind, so palpably imbued as none of his previous portraits had been with pathos for his subject. The paintings Lennart Anderson completed after his vision failed come to mind as well, particularly Jupiter Study and Lion Mask, both of which sound seemingly fathomless emotional depths.

As his sight worsens, Sacks’s brain fills in missing visual information, and he becomes curious

Sacks’s doctor assured him that his tumor could likely be removed without unduly jeopardizing his sight. As it turned out, Sacks was not so lucky, and the radiation and laser treatments left him with a large scotoma that greatly obscured his right eye’s central vision. But the story of what Sacks saw did not end there.

In “Persistence of Vision,” it is fascinating to watch Sacks, with his inveterate interest in the workings of the mind, turn himself into a case study. Alone with his condition, and ever curious, he paid close attention and made detailed notes about what he saw throughout his ordeal, knowing that some portion of what he believed he saw was being generated by his mind in the absence of visual acuity.

His first remarkable vision occurred in the hospital after radiation therapy, when, with his right eye covered by gauze and a rigid eye patch, his scotoma became more like a window than a blind spot, “through which [he] saw strange buildings, figures moving, little scenes playing themselves before [him],… writing, jumbled letters that [he] could not read—hieroglyphs or runes—all over the scotoma.” These images didn’t come from the cells firing in his eyes, but were constructed by his brain, “calling, if indirectly, on its stock of images.” He also noticed that if he was looking at something and closed his eyes, he continued to see it so clearly he doubted his eyes were actually closed—what he called a “genuine persistence of vision.”

When, several months after his initial diagnosis, he underwent a final laser treatment that left the central vision in his right eye obscured by a “huge black opacity,” he discovered more about his persistence of vision. The black blob camouflaged itself: filling in to become a white ceiling, a blue sky, or a brick wall, depending on what Sacks was looking at. There were “strict limits” to this filling in, though—faces, people, and complex objects could not be simulated. After gazing at something and closing his eyes, he would continue to see the scene for ten or fifteen seconds in “great, almost perceptual detail.” He writes: “I had the sense that my visual cortex was now in a heightened or sensitized state, released to some extent from purely perceptual constraints.”

“I had the sense that my visual cortex was now in a heightened or sensitized state, released to some extent from purely perceptual constraints.”

Many people with sight loss share Sacks’s experience of “filling in” missing visual information

What Sacks experienced is similar to what many other people have described when they lose their vision, including Frigyes Karinthy, the Hungarian author who was the first person to propose the concept of “six degrees of separation.” Like Sacks, Karinthy had a brain tumor that interfered with his vision. In his autobiographical novel, Journey Round My Skull, he describes the filling-in phenomenon: “I stood on the threshold of reality and imagination, and I began to doubt which was which. My bodily eye and my mind’s eye were blending into one, and I could no longer be certain which of the two was really in control.”

Maybe the interdependence of eye and mind in the act of seeing can help to explain why visual artists are so often confounded when we interview them about what they see. One artist was aware that his brain was to some degree righting the tilt of buildings and filling in the blank spaces left behind by his deteriorating macula, so that he was no longer sure what he actually “saw” or whether it mattered. At the same time, for some artists, the brain’s visualizations, whether they be “filling in,” remembered scenes, or hallucinations, can become the subject of new work and fresh visions. This was the case for Thomas Sgouros, who left off painting from perception when he got macular degeneration to paint landscapes from memory (what Sgouros called his “remembered landscapes”). The English artist Cecil Riley has made his post macular visual hallucinations the subject of his late work.

Finding a new way of ordering one’s world

Sacks ends “Persistence of Vision” as a man who has gone completely blind in one eye. He’s trying to adjust to the loss of stereoscopic vision and the profound, bewildering sense of “nothingness” and “nowhere” on his right side.

“Going blind, especially in later life,” he writes in another essay that appears in The Mind’s Eye, “presents one with a huge, potentially overwhelming challenge: to find a new way of living, of ordering one’s world, when the old way has been destroyed.” What makes this statement (and Sacks’s work, by extension) so meaningful is its reassurance that the story will continue, that life will go on. There will be a next chapter after disease, after handicap, after disorder, after loss, where the human body, mind, and imagination mysteriously and creatively intersect.

What Sacks illustrated over and again is that the next chapter will depend upon the individual. As such, the story is never the same though the affliction may be shared. To document the struggles and adaptations of people who are living with conditions we commonly categorize as illness and/or disability, to tell their stories (at least as Sacks tells them and as we hope to, with attention and compassion), is to privilege the individual over the disease. What we see under this narrative lens are lives where physical and mental challenges are not afflictions, but states of being that call upon and draw forth a person’s innately creative self—to find alternative pathways, articulate new visions, craft new ways of living.

As a side note, many of us, including Sacks, neglect routine eye exams that detect and treat the early stages of vision loss. We may even ignore clear signs of visual disturbance—in Sacks’s case, close-set wavy lines he saw on the white ceiling of the swimming pool when he was doing the backstroke. Though there remains as of yet no cure for macular degeneration, early detection can help to slow the disease or lessen its effects considerably. If you haven’t had an eye exam recently, we encourage you to make an appointment now.

Comments

A lovely piece, especially because you combine paintings with Oliver Sack’s writing about his loss of eye sight. I knew Sacks slightly, after he endorsed a book of mine, but I wish to comment here on how the mind fills in when we lose part of our sight. I have had bleeds in both retinas, only partly healed, but I am mostly aware that, even with some loss of sight, I supply the missing pieces through cognition, or through memory, or through expectation. It doesn’t feel like a loss to me, maybe because the mind is still seeing — at the age of 85. A strange thing I have noticed over the years is the way I continue to see the road and buildings and traffic, etc. after I have left the highway. These “visions” have remarkable clarity and detail, but they fade after a few minutes. Thank you for this article!

Leave a Comment