William Thon

1906 - 2000

“My eyes are in my fingers.”

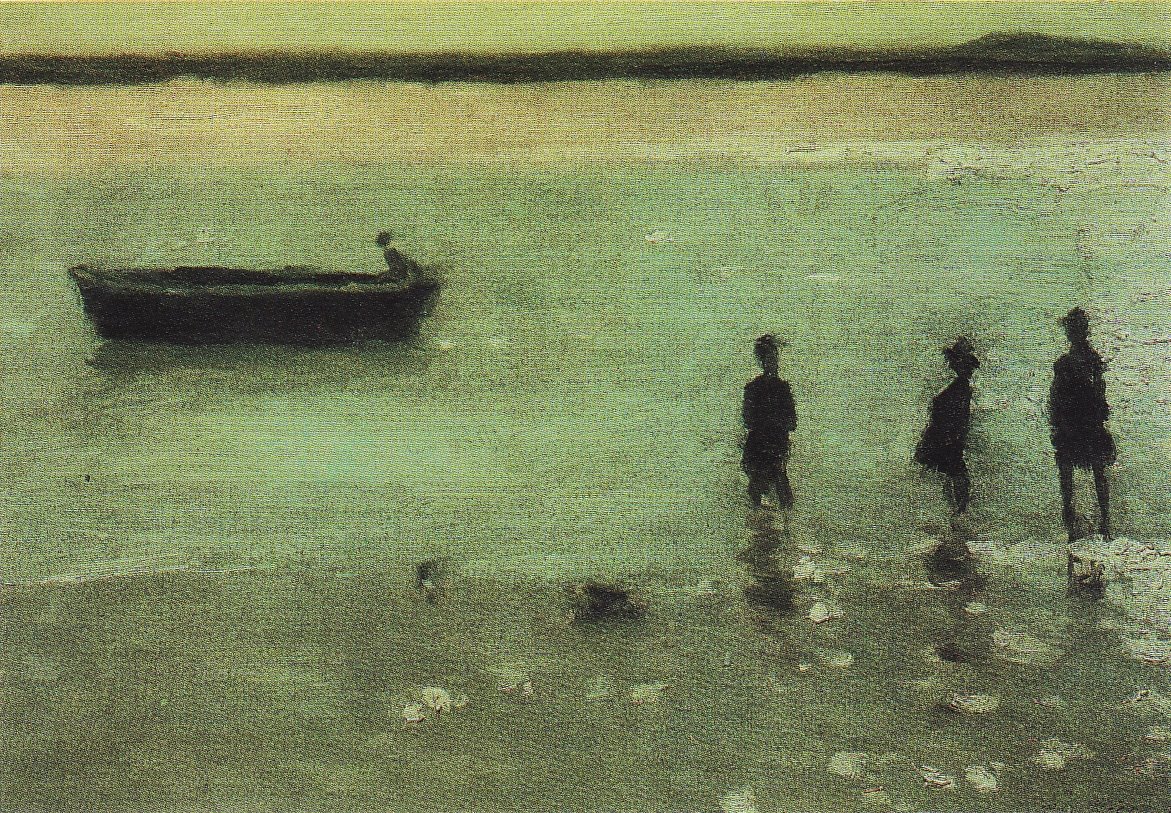

William Thon in a 1996 painting Demonstration at the Farnsworth Art Museum

Biography

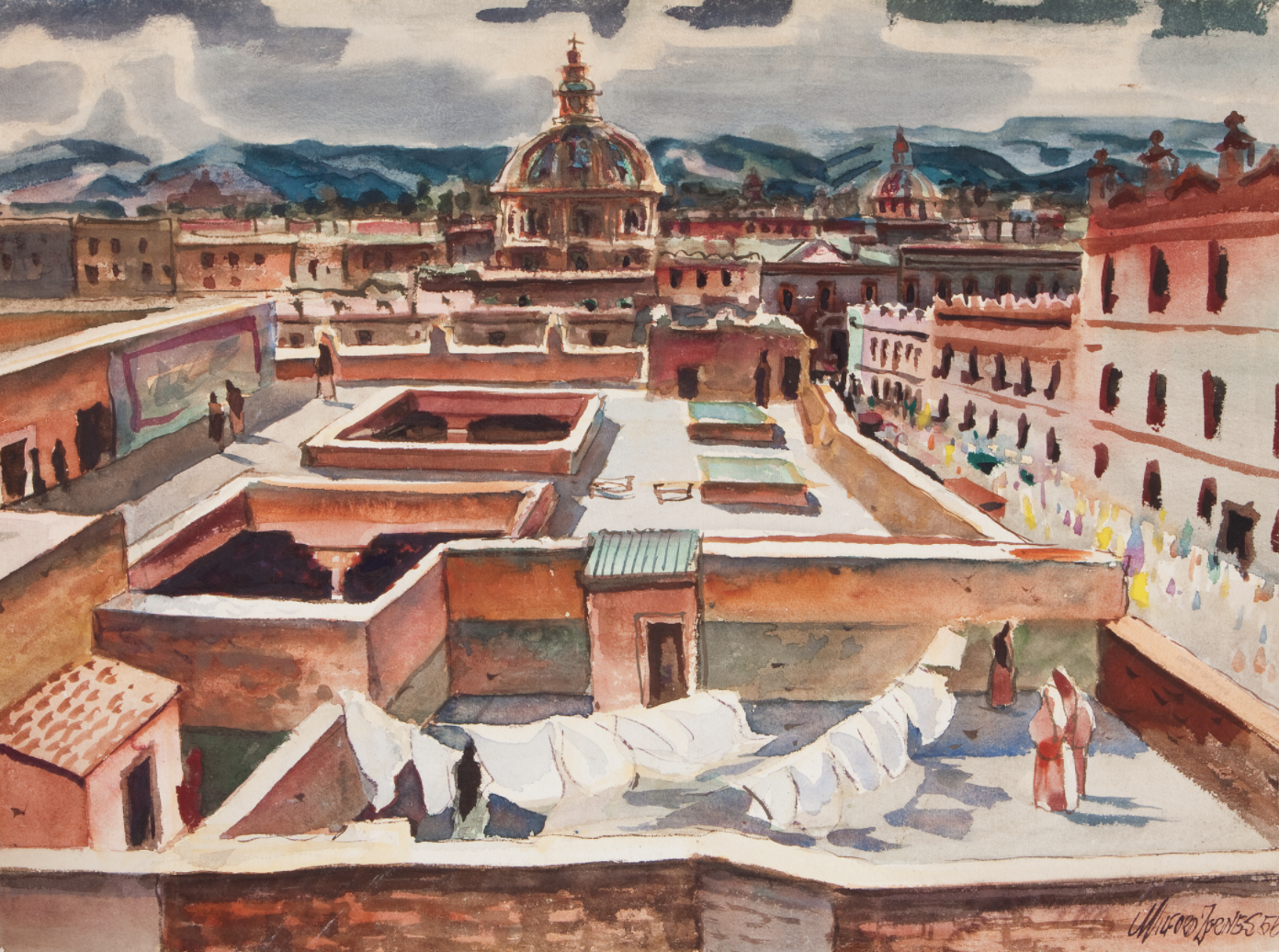

Born in New York City, William Thon had no formal art training beyond a brief stint at the Art Students League. He served in the Navy during World War II and shortly after the war won the Prix de Rome, followed by a fellowship from the American Academy in Rome, where he later served as a trustee and Artist in Residence. He held an honorary doctorate from Bates College in Lewiston, Maine, and was a member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, as well as the National Academy of Design.

Awarded numerous prizes, Thon regularly exhibited his work during his lifetime and was the subject of a 1964 book by Viking Press, The Painter and His Techniques. Thon’s work is in over 60 museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Butler Institute of American Art, Columbus Museum of Art, Farnsworth Art Museum, and Portland Museum of Art.

Thon’s post-macular artwork

Thon was diagnosed with macular degeneration in 1991, the year before he was interviewed by Robert Brown for the Archives of American Art. In the interview, Thon mentions that he had not been able to paint in oil for a year and was working entirely on white paper with black paint, since he couldn’t see color anymore.

A few years later, Thon demonstrated his post-macular method of working at a forum on visual impairment at the Farnsworth Art Museum.

Using his hands, Thon navigated by feel from the front of the demonstration table to the back, faced his audience, and began to paint. On the table was a blank sheet of paper. He spritzed it with water, caressing the surface in circular motions with his hand, in so doing seeming to take stock as a dowser might of what lay beneath.

He picked up a brush, and said, “My eyes are in my fingers.” At the top and bottom of the paper, he then drew two generous pools of black paint horizontally from left to right. The black lake of pigment bloomed on the wet surface in ever fainter ghostings of value. He then leaned down close to the surface of his work, his nose inches from the paper, and began to blow softly, so that the paint began to quiver. With a putty knife, he gently scraped upward from the bottom of the paper, revealing the trunk of a birch tree. This gesture he repeated until several trees stood in a wood. Then, with a thinner knife and slightly different gesture, branches.

As he dipped a quill pen into pot of India ink, he said, “I remember the small branches on birch trees were generally black, so I will use India ink for that purpose.” He blew across the paper again, to push the “color around a bit, because it floats on the surface of the water.” Finally, he looked at parts of the painting through a magnifying glass: “I’m trying to see what I have done,” he explained, and dabbed at some of the black pools on the paper with a bit of paper towel to pull out lights.

V&AP Resources Related to This Artist

Feature Article

Lessons in Creativity from Artists with Macular Degeneration

Eight artists from one generation and how they continued making art after vision loss due to macular degeneration.

Read More