Robert Vonnoh (1858–1933)

1858 - 1933

During the last decade, Mr. Vonnoh’s sight had failed, and he had virtually given up painting except in a desultory way.

—The New York Times, December 29, 1933

Biography

A pioneering figure in the development of American Impressionism, Robert Vonnoh was born in Hartford, Connecticut. His father, a German immigrant, was a cabinetmaker. As a child, Vonnoh moved to Boston with his family and began his art studies at fourteen, working in a lithography shop and taking mechanical drawing classes at the Boston Free Evening Drawing School and the Massachusetts Normal Art School.

Vonnoh graduated from Massachusetts Normal in 1879 and began teaching there and at several academies in Boston while exhibiting his portrait drawings at the Boston Arts Club. In 1881 he moved to Paris to continue his training at the Académie Julian under Jules-Joseph Lefebvre and Gustave Boulanger. Two years later, his portrait of fellow art student John Severinus Conway was accepted for the Salon des Beaux-Arts exhibition in Paris, at that time one of the most prestigious annual art events in the world. Vonnoh returned home to Boston and began teaching, first at the Normal School and the Cowles Art School, and then, starting in 1885, at the Museum of Fine Arts School. At the same time he began to build a career as a traditional figure and portrait painter, exhibiting work in such places as the annual salon at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and at Chicago’s Interstate Industrial Exposition.

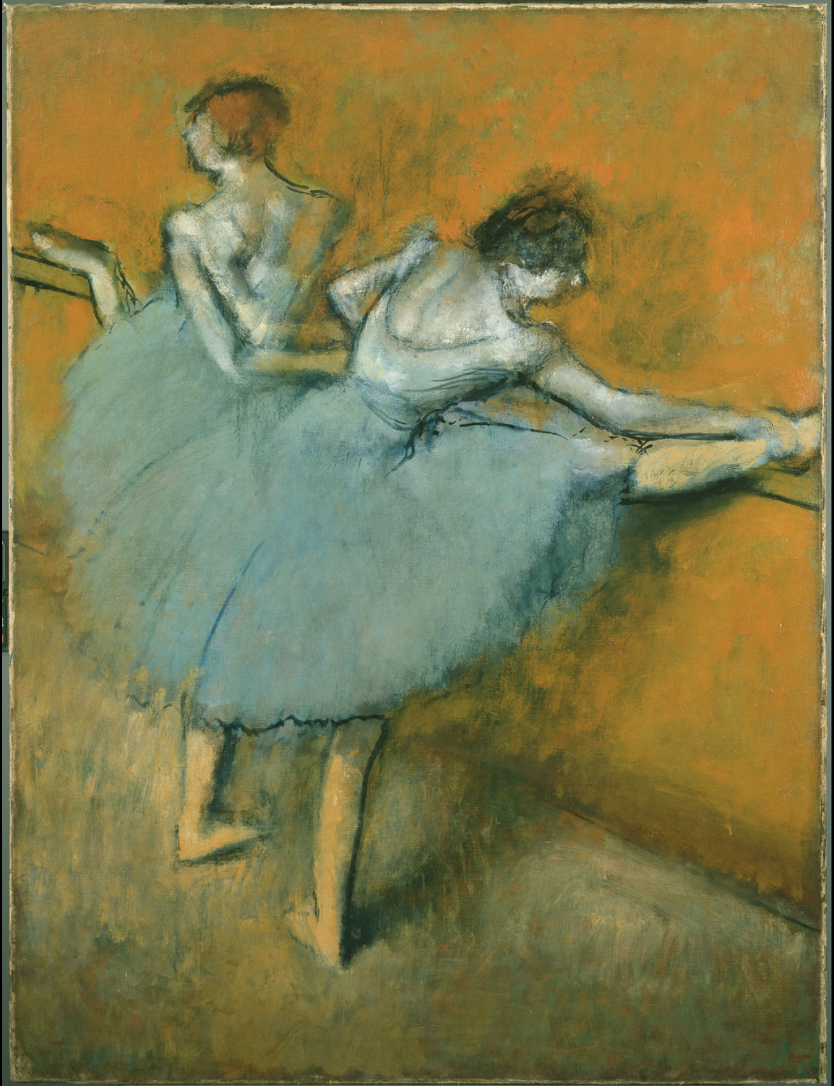

Vonnoh returned to France in 1887 with his first wife, the artist Grace Farwell. They settled in Grez-sur-Loing, which had been popular with plein-air landscape painters since the early 1870s. While continuing to paint academic portraits, Vonnoh also began to experiment with pure color and broken brushstrokes in his landscape paintings. In 1891 he again returned to the States, this time to be honored by a Boston gallery with his first solo exhibition and to begin teaching portrait and figure painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, a position he held for five years, now able to support himself financially through his art. Robert Henri, John Sloan, and William Glackens of the Ashcan School were among his students.

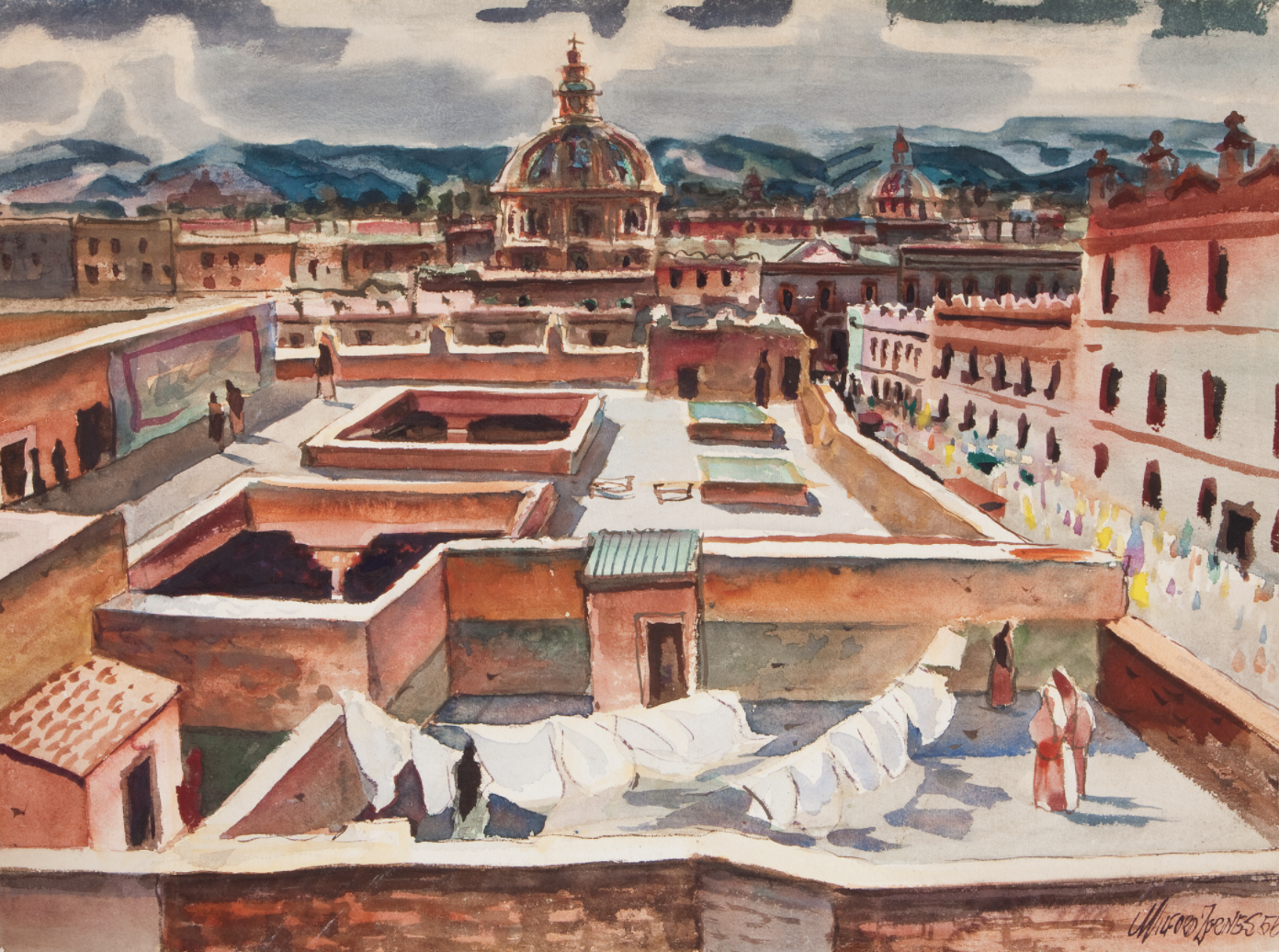

Along with his ties to the East Coast and France (where he returned repeatedly during his life and where he was to die in 1933), Vonnoh maintained a studio in Chicago for several years in the late 1890s. There he met his second wife, the sculptor Bessie Potter, whom he married shortly after Farwell’s death in 1899. Entwined both professionally and personally, Robert and Bessie Vonnoh maintained a home in New York City but also spent time in France and Old Lyme, Connecticut.

Robert Vonnoh’s work can be found in many museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Museum, the Butler Institute of American Art, the Florence Griswold Museum, the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Museums, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among others.

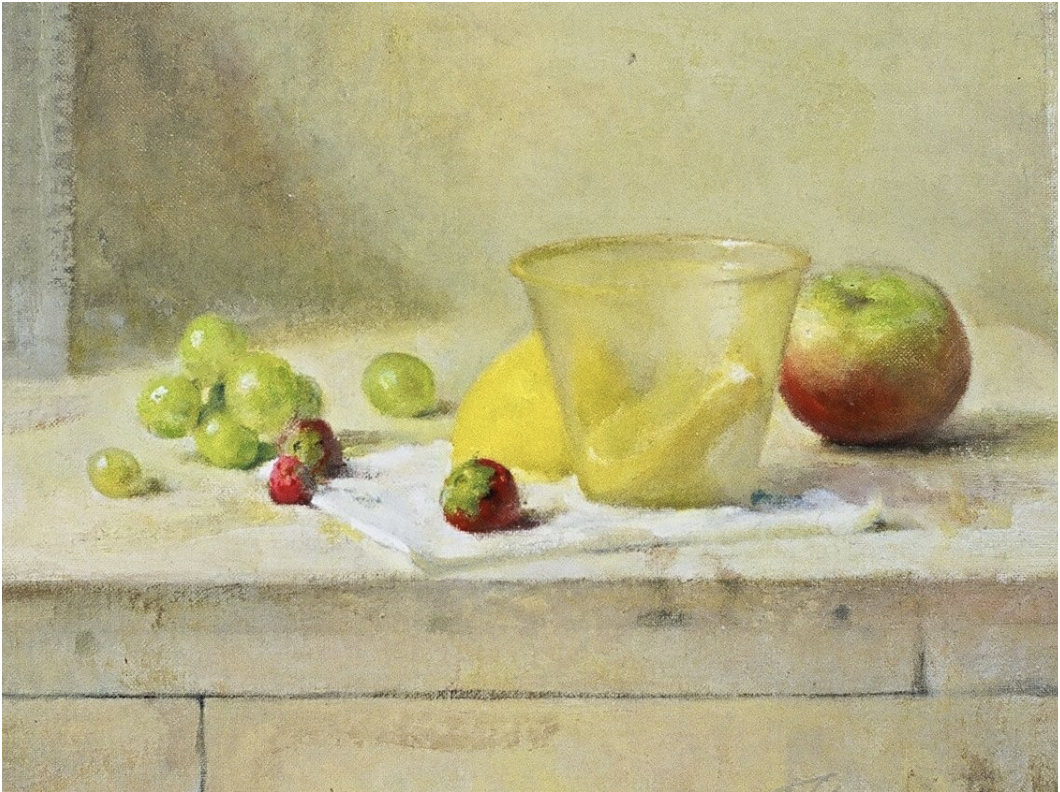

Throughout his life Vonnoh painted landscapes, figures, and portraits, at times employing a manner informed by impressionist color and light and at times employing a more academic, tonal approach to structuring the colors on his canvas. These shifting styles may be one of the reasons his artistic achievements have not yet been fully recognized and why he is not as well known today as his artistic achievements would merit.

Vonnoh’s post-macular artwork

Vonnoh’s eyesight began to fail in 1925, and, according to his New York Times obituary, in the decade or so before his death he had not exhibited his work in the United States, had spent much time abroad, and for the first time in his career was no longer receiving awards. Though there is little documentation of his experience with vision loss, it is not hard to hypothesize a relationship between Vonnoh’s vision loss, changes in his painting style, and his flagging career. His obituary hints at the stigma and shame that can often accompany what is perceived as physical decline. In it, his eyesight is described as having “failed,” his subsequent method of painting is characterized as “desultory,” and he is presented as someone who had once known the heights of fame, only to die alone and somewhat forgotten on foreign soil.

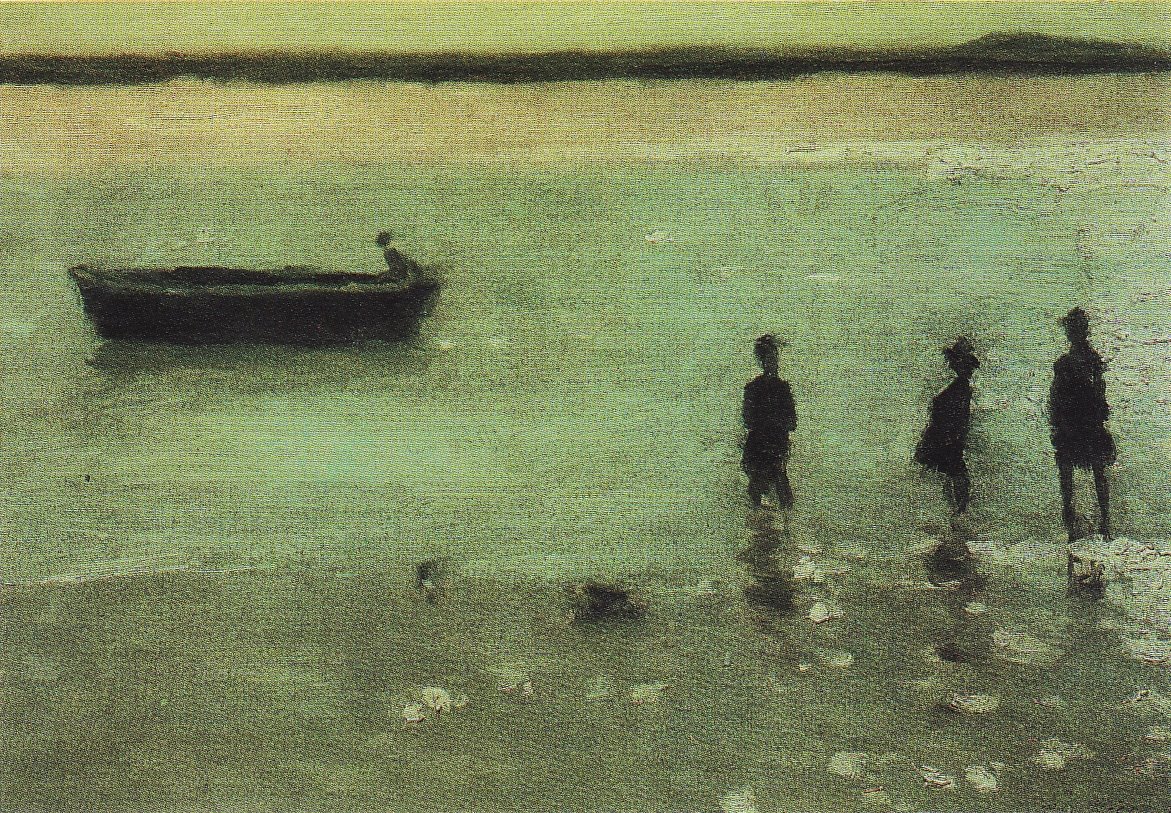

The trend that Wendy Greenhouse has perceived in Vonnoh’s late landscapes toward a “tonalist blurring of forms, poetic mood, and subjective rendering,” is present, for example, in the undated painting Pleasant Valley and is consistent with adaptations that we see in the work of other artists who have been affected by vision loss. Since records and references to Vonnoh’s vision loss remain scarce, however, at present it is impossible to know how and when his painting began to be affected by vision loss. Further research on this artist’s life and work may provide more answers.