Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer

June 02, 2022

A current exhibition, Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer, at the Addison Gallery of American Art deepens our understanding of the artist’s late work.

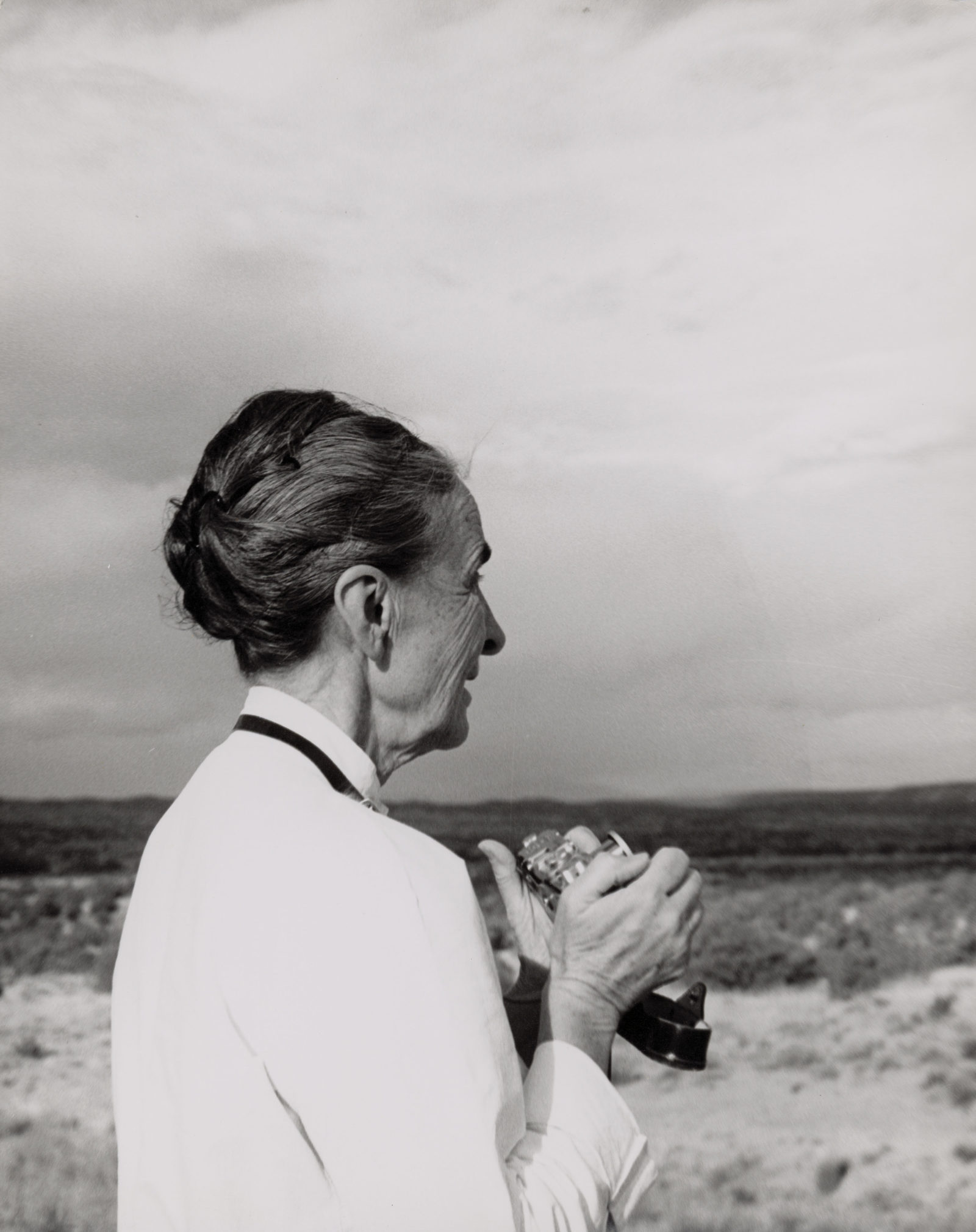

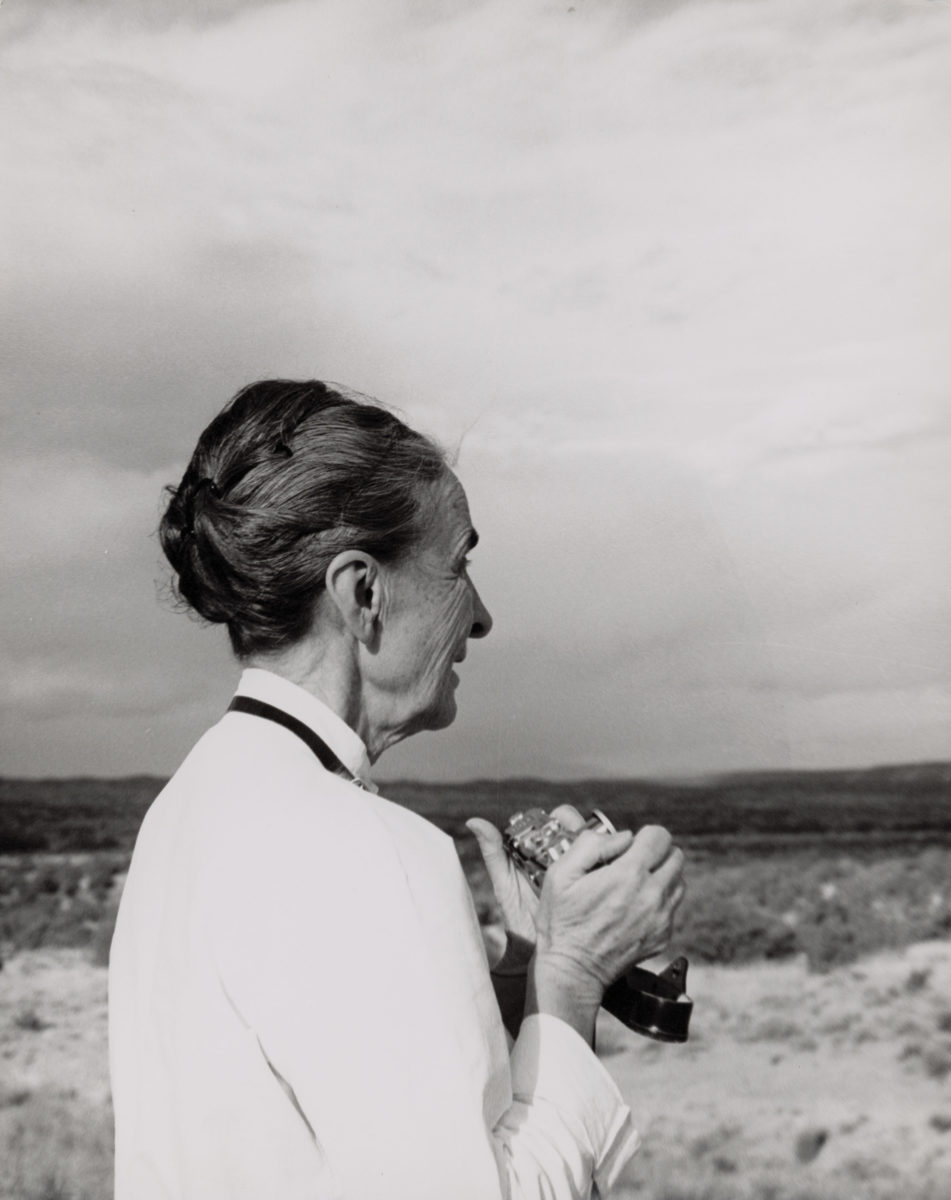

O’Keeffe as photographic subject and O’Keeffe, Photographer

At the recent Georgia O’Keeffe retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, visitors were entranced by the giant screen projecting photos of O’Keeffe. It was a visceral reminder of how integral O’Keeffe’s role as a photographic subject was to her iconographic status of an artist. Her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, began photographing her when they first met in 1917—she was 30 years old at the time—and would continue to do so for the next two decades. He took approximately 330 photos of O’Keeffe in all, creating a photographic portrait of her as she changed from a young artist and schoolteacher into an American icon.

Stieglitz was not the only one to take her picture. So too did some of the most renowned photographers of her time, including Eliot Porter, Todd Webb, Myron Wood, Dan Budnik, Marjorie Content, and Ansel Adams. It’s why when we think of O’Keeffe and photography, we might be excused for thinking of her only as a subject of the medium, whether as a young woman posed bare shouldered looking into the camera (at Stieglitz) or an old woman posed many decades later with her veined hands on a clay pot.

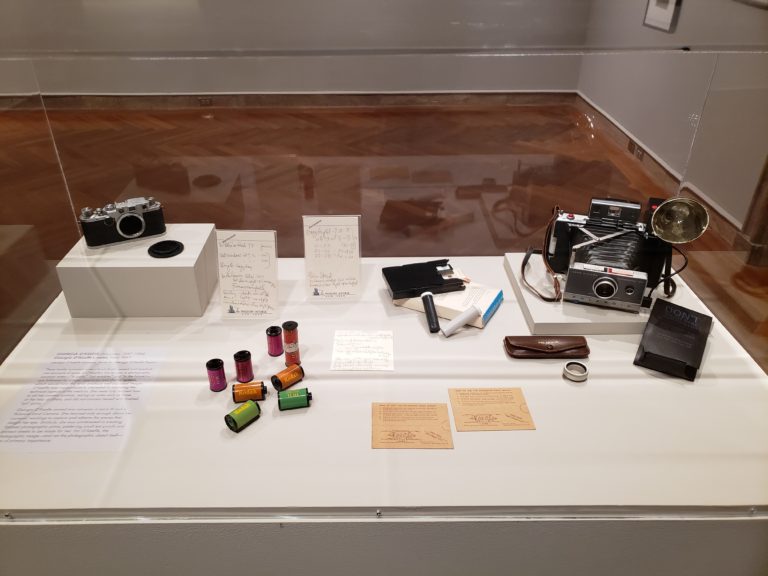

Yet along with having been one of the twentieth century’s most charismatic photographic subjects, O’Keefe also stood behind the camera. Until she was 70, she took pictures for much the same reason as anyone does — as mementos of travels and daily life. But beginning in 1957, with the help of Todd Webb, she used the camera as part of her artistic practice. Several of her photos from this time are in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but most are in the archives of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Somewhat astonishingly, they only recently began to be studied when Lisa Volpe, associate curator of photography at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston (MFAH) organized an exhibit there, Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer, now at the Addison Gallery of American Art (through June 12, 2022).

Nearly 100 O’Keeffe photographs from a newly examined archive are on view

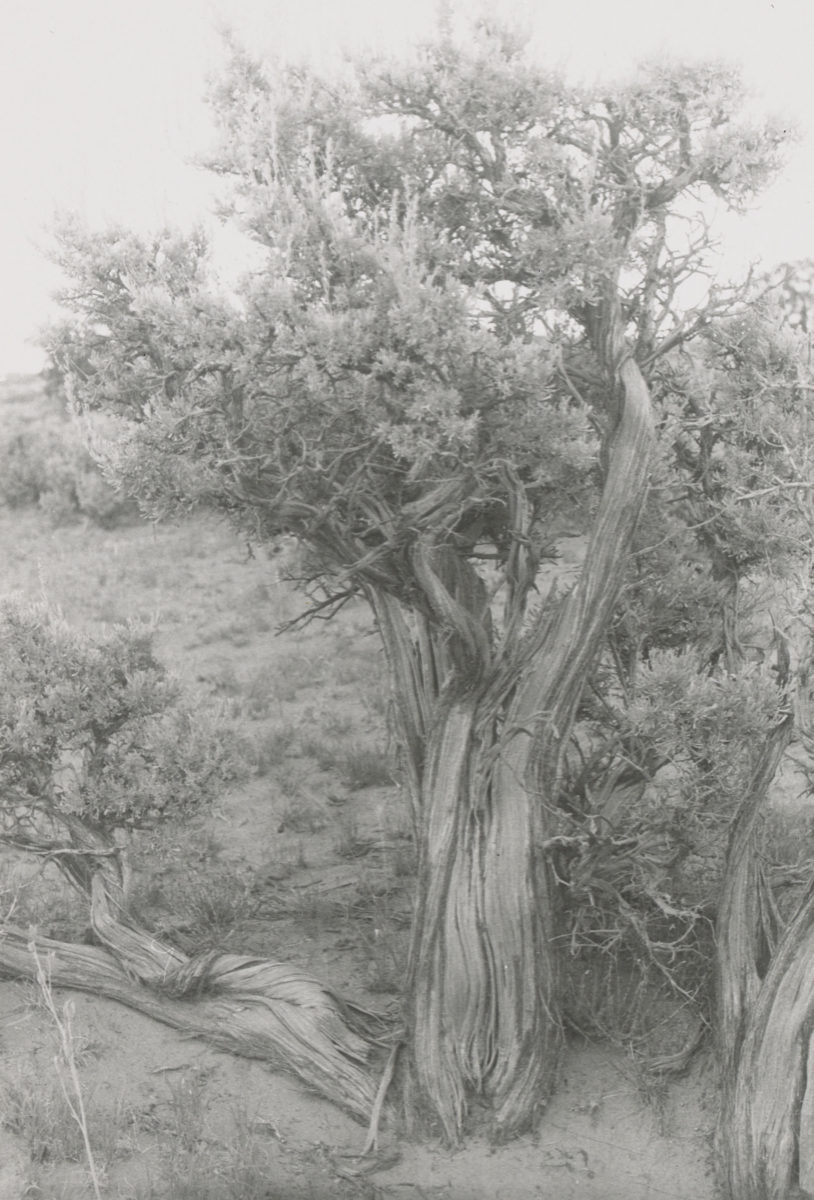

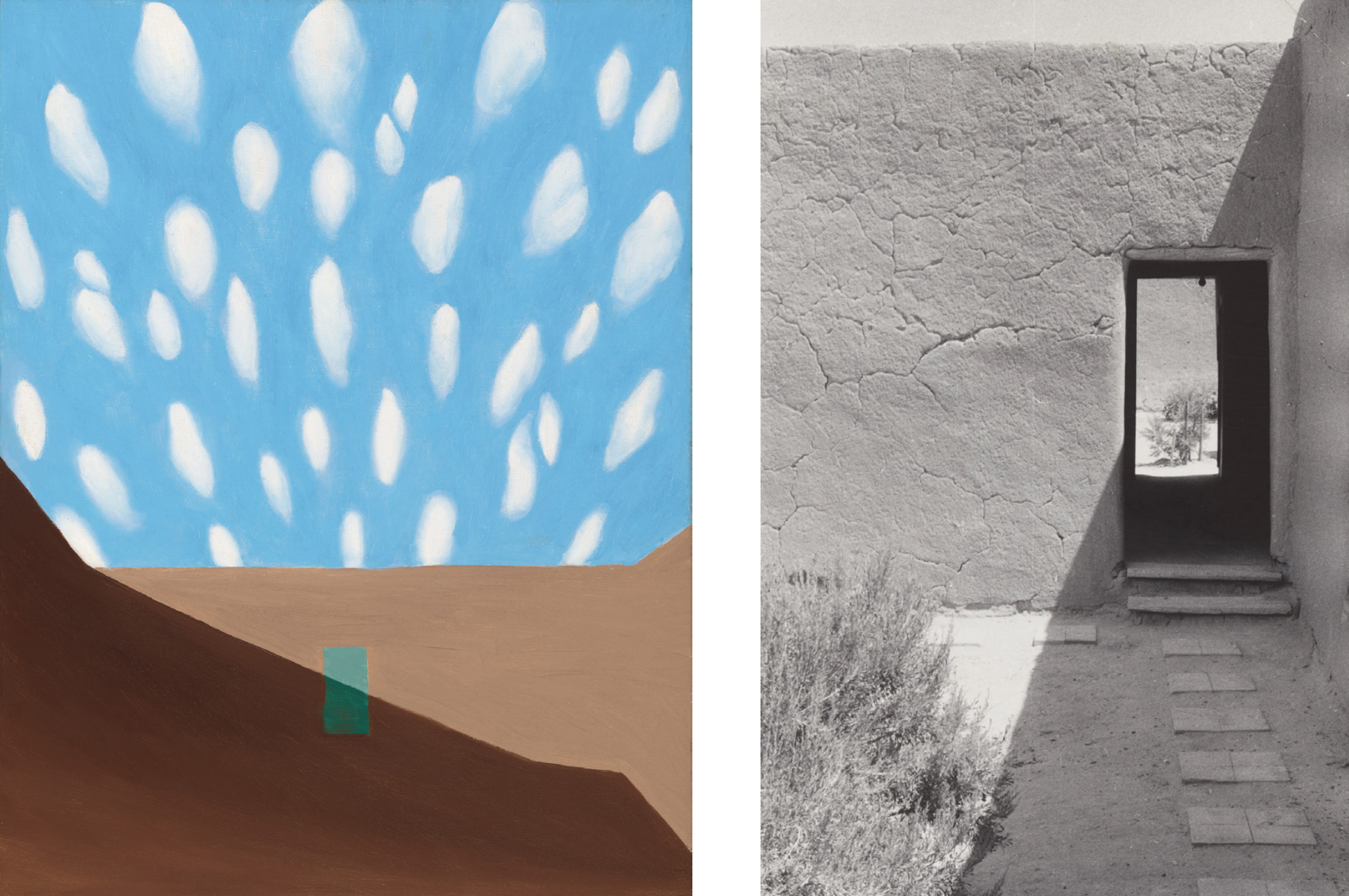

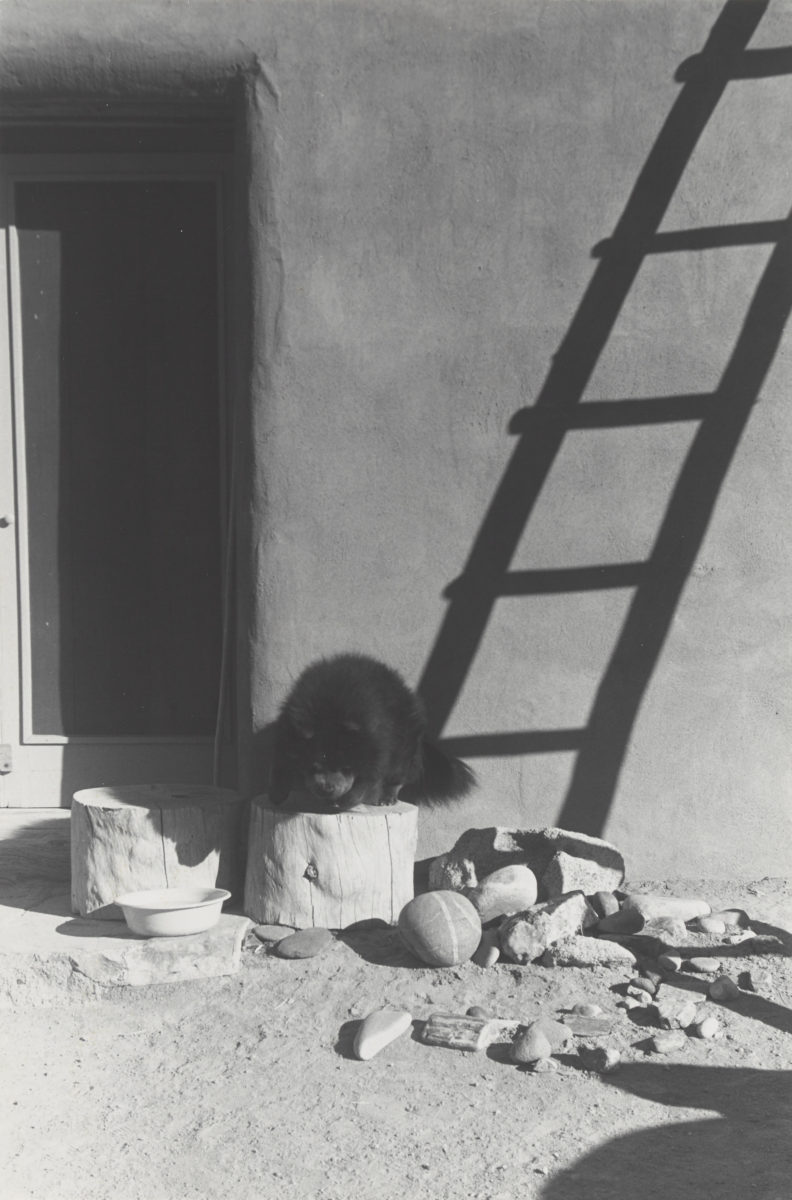

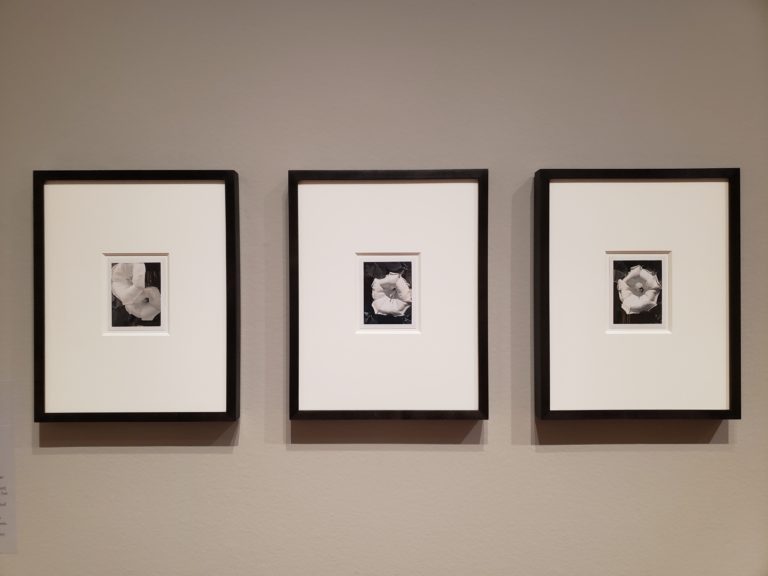

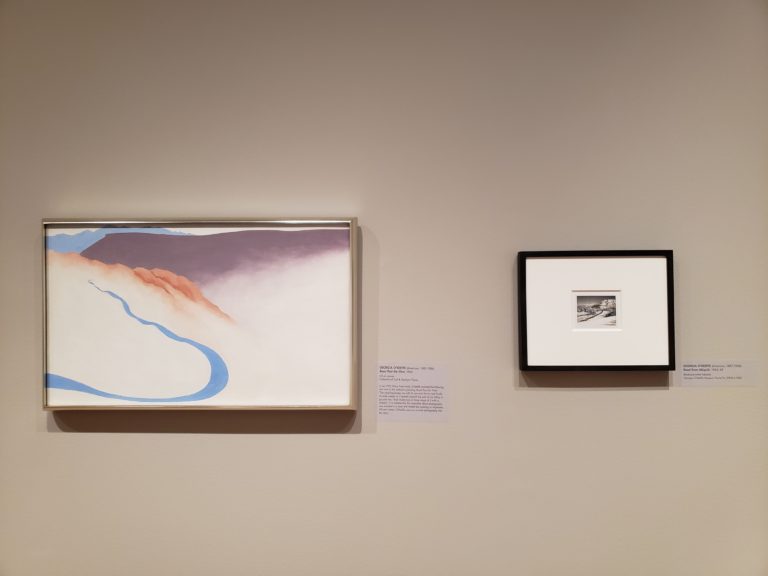

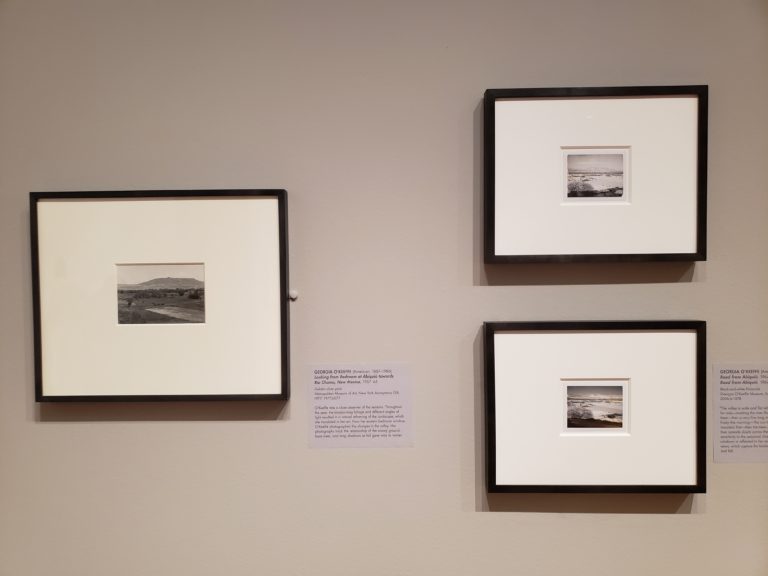

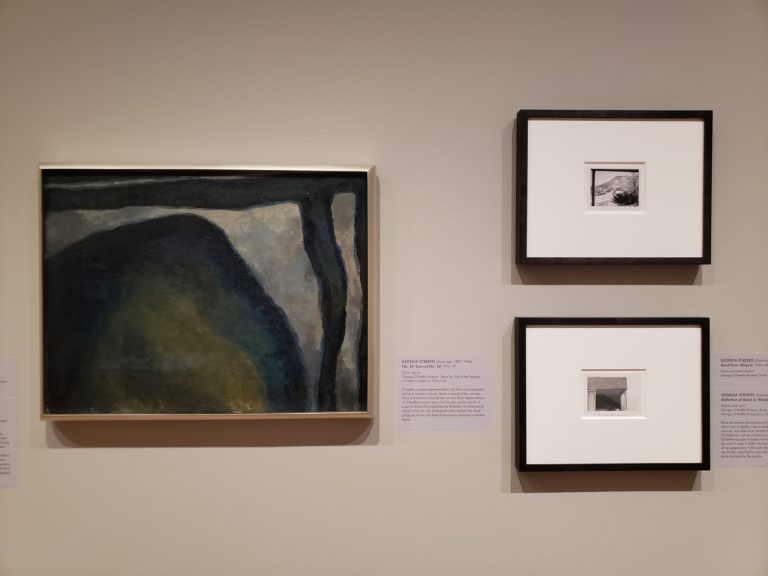

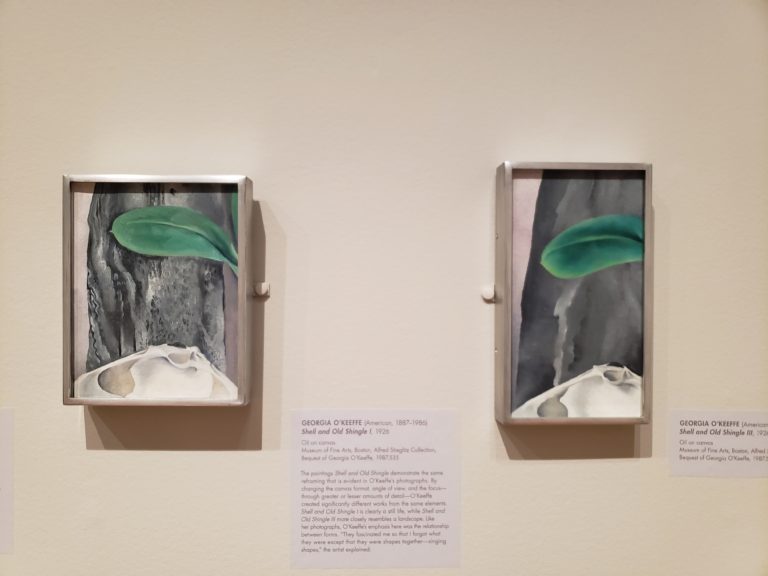

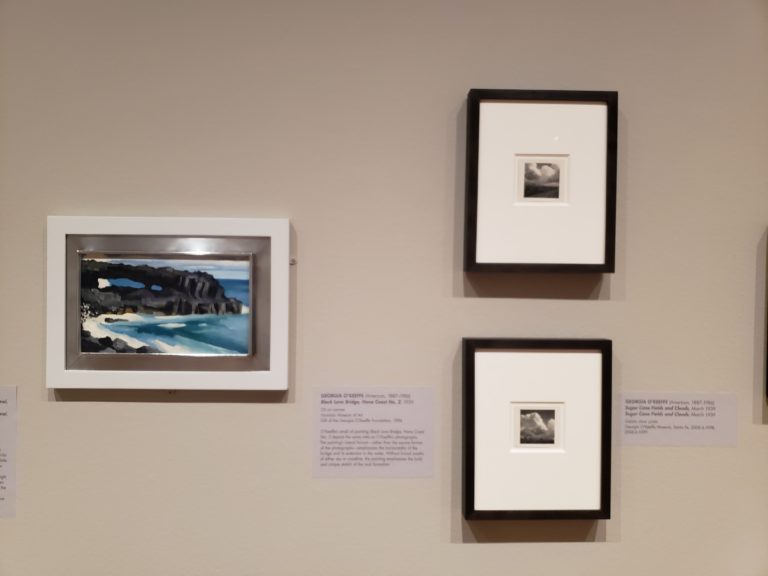

Nearly 100 photographs from the newly examined archive are on view. All are black and white—“snaps,” as O’Keeffe often referred to them—complemented by the presence of several of her drawings and paintings. The photographs are of the same subjects that constituted O’Keeffe’s paintings: Jimsonweed flowers, a ladder against a studio wall, sage trees, salita doors, the road from Abiquiú.

I didn’t really see them as works of art unto themselves but as notes, references, and clues as to how O’Keeffe thought and what she sought to see. They show how O’Keeffe constantly framed and reframed the same scenes in order to distill the visual essence that was at the center of her painterly vision. While the photographs are clearly of the same artistic mind as O’Keeffe’s painting and therefore utilize the same characteristic techniques, they shed new light on O’Keeffe’s working process and raise questions about why she used photography as part of her late-life working practices.

O’Keeffe’s photos show her fascination with the interplay of light and dark

O’Keeffe was educated at the Art Students League by William Merritt Chase, with an approach to drawing and painting rooted in the Old Masters. But her signature style is not obviously beholden to a traditional sense of shadow and light meant to create an effect of illumination and an illusion of three-dimensional form. Indeed, after leaving the Art Students League, where she made more traditional paintings, such as “Dead Rabbit with a Copper Pot,” she eschewed that way of working as being inconsistent with how she saw the world and what she wanted to express.

And yet, it’s obvious from this exhibit that one of the things that O’Keeffe was studying most intensively as she worked in series was the interplay of light and dark, and that she used patterns of light and shadow to organize her canvases much as a more traditional painter like Chase might. Amid the occasional paintings on display, O’Keeffe’s black and white photographs seemed to me at times akin to the monochromatic underpaintings and studies of Old Masters: as in an underpainting, O’Keeffe’s photos fixed the distribution of darks and lights for subjects she was going to paint.

Forbidding Canyon, Glen Canyon series: tracking a day’s light

This is most striking, perhaps, in the series of photographs Forbidding Canyon, Glen Canyon series, all taken in September 1964. The photographs track how, throughout the day, the light changes the visual appearance of the monumental form of two cliffs meeting in a V shape.

In the first photo, the two cliffs are equally lit and are fused into a single geometric shape against a pale sky. In the next, the sun’s position turns one cliff into a bright white form while the other, cast in shade, becomes a dark mass. Then, the shadow begins to eat away at the light on the brighter cliff one geometric shape at a time, until, with the last image in the series, both cliffs are fused again into a single shape against the sky. In the last photo, the fused shape is much darker than in the first, thus capturing over the range of the series the passage of time and deepening dusk to emotional effect.

Of the photos she took, that of the shadow beginning to eat away at the bright cliff appears to have been most compelling to O’Keeffe compositionally, since it informed a 1965 charcoal drawing and oil painting she did of the scene.

O’Keeffe’s photographs show her to be carefully studying the effects of natural light on form—that is, to be receiving impressions that would inform her compositions and the way she designed her canvas. Fascinatingly, they also reveal her design sensibility and how she adjusted scenes to amplify the visual qualities she sought to express in paint.

Ladder against a Studio Wall series: bright white forms, weighty dark objects

In the series of Ladder photos (against a Studio Wall), she photographs a ladder at different angles to the wall and at different times of day, which in turn changes the shadow’s shape and, with it, the appearance and feeling of the scene. But she also manipulates the scene in other ways. Much as a still life painter might experiment with the arrangement of objects on a table, so O’Keeffe experiments with adding objects to her scene. In one photo, she has placed a shallow white bowl on the ground; in another, her black chow. She also adjusts the frame, repositioning the camera to capture only the ladder’s shadow and the dark door to its left, creating noticeably different compositions through the subtle arrangement and rearrangement of bright white forms and weighty dark objects.

That this is also the foundational vision behind many of her bright paintings is often not immediately apparent from the look of the paintings themselves. So, in essence, what is somewhat hidden from view in O’Keeffe’s finished works, is visible in the photographs.

The exhibit left me with questions

Though the exhibit offered access, of sorts, to O’Keeffe’s eyes and way of thinking, it also made me acutely aware of what we don’t have access to about her, at least in the context of this show.

Why did O’Keeffe turn to the camera as a compositional tool beginning in 1957? She always worked in series, and a look through her catalog raisonneé reveals paintings in series that show exactly the kinds of adjustments and readjustments she made in her photographs—her 1938 series of a Hawaiian waterfall, for instance. From 1957 on, she continued to paint multiple iterations of the same subject; why did she also pursue this aim through the photographs? Were they meant to be a record or an aid or something else altogether? Most of the photographs in the exhibit are from the late fifties and early sixties. Once she started taking pictures as part of her artistic practice in 1957, did O’Keeffe continue to do so for the rest of her artistic career?

Also, somewhat related to these questions, how did she use her photographs (if at all) during the painting process? One of the many photos by Todd Webb included in the exhibit is of O’Keeffe’s studio. A white canvas is primed and ready on an easel, to the left of which is her subject (a simple branch) and to the right of which, on the wall, is an earlier painting she did of the branch. A small table, on which are two jars with brushes. Nowhere in sight are the typical accoutrements of an artist’s studio—books, reproductions, photos, artifacts. Did she, like some other artists do, use photographic references while she was painting? In an essay for the catalog that accompanies the exhibit, Volpe notes that some of the photos had tape on the back, as if they’d been tacked up—on the studio wall? Or somewhere else?

O’Keeffe began using photography as part of her artistic practice at about the same time that her work underwent a marked change. She started making fewer paintings. Those she did make were, in general, simpler, more abstract, more explicitly concerned with metaphor and evoking transcendent states of being. Is there a connection between this change in her work and her use of photography? And, given that O’Keeffe was 70 when she began taking photos as part of her artistic practice, were they a sign that she was adapting her working practices to accommodate an aging body? In 1964, she apparently sought treatment for vision loss. Did macular degeneration perhaps affect her vision earlier—and inspire her to take black and white photos as an aid to seeing?

Whatever one thinks of these questions, the chance to see the photographs that provoke them is one no Georgia O’Keeffe fan will want to miss.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer, will be traveling to the Denver Art Museum (July 3 through November 6, 2022) and the Cincinnati Art Museum. While the O’Keeffe exhibition is on view at the Addison, you can also see an exhibition of the work of O’Keeffe’s Arthur Wesley Dow, whose ideas were formative to O’Keeffe’s development as an artist: Arthur Wesley Dow: Nearest to the Divine (through July 31, 2022).

Further Reading

Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O’Keeffe in Paris

O'Keeffe's planetary perspective shines through at the Centre Pompidou's retrospective of her work, a cosmos outside human presence.

Read More

Leave a Comment