Freedom from Specificity

March 23, 2024

(The following essay by Alice Mattison is excerpted from the catalog that accompanies the exhibition, What Was Once Familiar: The Vision & Art Project’s Tenth Anniversary Benefit Exhibition, which was on view at the National Arts Club in New York City this spring and will remain available online through December 31, 2024. Additionally, several works from the show are currently on view at The Lighthouse Guild, on West 64th Street in New York City.)

Artists generously spend their lives letting the rest of us see what existed originally only in their minds. They know that imagination is different for each person, and somehow have enough faith in their own to create what it suggests. We speak of their vision, their personal viewpoint. Maybe artists also understand, more easily than the rest of us, that literal vision, a literal viewpoint, is unique as well. They work with their hands, but seeing—their particular sort of seeing, supplemented by imagining—tells them about art in the first place. Though we talk as if we all saw the same things, eyesight is a little different for everyone, even for those who have perfect vision on an eye chart. We’re each alone with what we see, both literally and figuratively. Art frees us from that solitude.

But what happens when an artist’s eyesight becomes significantly flawed—when things look different, when the work of art itself may be hard to see, when familiar techniques are no longer easy or no longer possible? The artists in this show, all of whom have macular degeneration, learned firsthand that vision isn’t always the same when their own changed. Whatever their training and experience, they could no longer make art just as they used to. Age-related macular degeneration begins in late middle age or old age, when we are used to how we see: it’s ours. Even the genetic form of the disease, which starts earlier, doesn’t begin in infancy. And it’s not static. For some people, the changes are fairly abrupt, but for many of us with macular disease—I have it too—vision changes slowly. We become aware now and then that it has changed again: our sight is not what it was five years ago, and not what it was six months ago. Maybe the change is a disaster, or maybe it’s merely interesting. Or maybe it’s a disaster that is, at least, interesting.

Out of that disaster, or possible disaster, some artists continue to work. The art in this exhibit reflects what occasioned it: it is intense, suggesting both sorrow and joy—there may be grief in what happened but there is joy in responding to it in paintings, photographs, or sculpture—and it is beautiful. There are many reasons to be grateful to the Vision & Art Project of the American Macular Degeneration Foundation for putting on this exhibit. One is that the show demonstrates, if such a point needed to be made, that artists with this disability are not people whose only role is to receive help; they give the rest of us something remarkable. Looking at art made by artists whose vision has diminished makes us newly aware of the differences in the ways we all see. Some people confuse impaired vision or legal blindness with the absence of sight, but the artists who produced this work could see. Macular degeneration results in a small or large blind area at the center of one’s vision—the part of the eye that makes reading possible—but people who have it retain peripheral vision: we may not be able to see a face or read a word, but we see, at least dimly, what surrounds it. This disease does not lead to total darkness—the absence of sight—nor to a view that looks vandalized. Images on the web of what people with macular degeneration see look like photographs on which someone has spilled black ink, but the reality seems more natural than that. Sometimes it’s like seeing in twilight or mist. Or like seeing people or objects as if they’re in deep shadow, as if the room is dimly lit. Gaps in my own vision make it look as if uneven lighting hides what should be visible, or an object is warped, with areas worn away. The viewer doesn’t see a recognizably marred reality; reality is different: the sign painter or editor left a word out; the woman coming along with a dog has ceased to exist. Each artist here—like anyone with macular troubles—has a slightly different experience, depending on how fast the disease came on, how bad it got, whether it responded to treatment (in recent years, injections have preserved the sight of many of us, but they don’t work on all forms of the disease), or whether a blind area happens to be small or large, absolutely central or slightly to the side. Looking at these artists’ work, we see a little, through their eyes, of what they saw, and maybe what they felt as they depicted what used to look different. The melancholy that suffuses much of this work results partly from the increased darkness that macular degeneration patients experience, but surely also from what they think and remember. Looking at any work of art gives us insight into the artist, but maybe that’s even more true when we see the art of people who are noticing their sight, worrying silently about sight or talking to doctors and friends and anyone who will listen about sight, and, often, changing their practice so as to continue to make art with damaged sight. Seeing the art in this show offers the pleasure of seeing any good art, but more than that.

No one would have thought to show the work of these particular eleven artists together if they didn’t all have the same eye disease, but putting on this show makes sense. Macular degeneration isn’t merely a deprivation: it gives us something different to look at, which for me at least (I’m in better shape visually than most of these artists) can be a weird sort of found art. Watching that woman and dog appear and disappear as my eyes shift sometimes feels right for these uncertain times, and knowing that these artists experienced something comparable makes me curious about how they responded. Because the exhibit includes both early and late work, it gives us clues. The artists had always been dissimilar, and their eyes changed differently, or they reacted differently, but they faced a comparable problem. If they were artists before their symptoms began, did they try to keep doing what they’d done before? Did they deliberately make different art? Or similar art that came out different because their eyes changed, or because they changed? Impaired vision may be a spiritual or emotional convenience: what’s missing makes us focus on what we do see, and that takes on more meaning and intensity.

Thomas Sgouros’s impeccably detailed still life of oil and vinegar cruets, with a glass salt shaker in front of them—all reflected on a tabletop—can almost be seen as a celebration of good vision. The objects are the center of this painting, and there’s no periphery: the background is a wash of subtly mixed pale color that focuses our attention back on the objects. In contrast, two Remembered Landscapes, painted after Sgouros’s vision changed, have almost no foreground, nothing you’d need central vision to look at. But land and sky can be seen easily by someone who has only peripheral vision. The skies above these landscapes are full of excitement: interesting shape, surprising color—blue clouds, orange clouds. The paintings are rich and complicated whether you have central vision or not.

Also startlingly different are two black-and-white drawings by Hedda Sterne, one from before she had eye problems, one after. The early one looks like a strange plant whose elaborately ruffled leaves are covered with complicated shapes and cross-hatchings, each a bit different. Like Sgouros’s still life, it seems to take pleasure in displaying what eyes can see, what fingers holding a pen can draw. In Sterne’s drawing from after her eyesight diminished, however, a few lines give us the shape of a woman bending over, her arms in a position that makes us know she’s holding a baby. She’s crouching a little as if she’s just picked the baby up, holding her arms stiffly, as one does: to support the head, to make sure not to drop the child. The stance reveals the woman’s emotion. The whole is as if glimpsed out of the corner of one’s eye. It’s almost not there: at first glance one might see only lines, some darkened. Sterne is doing what she sometimes did earlier—drawing—but this drawing is so minimalized that it becomes new. It’s slight but powerful. In both these examples, the artist used a familiar medium, but altered the subject matter. Both found something that could be depicted with the vision they now had.

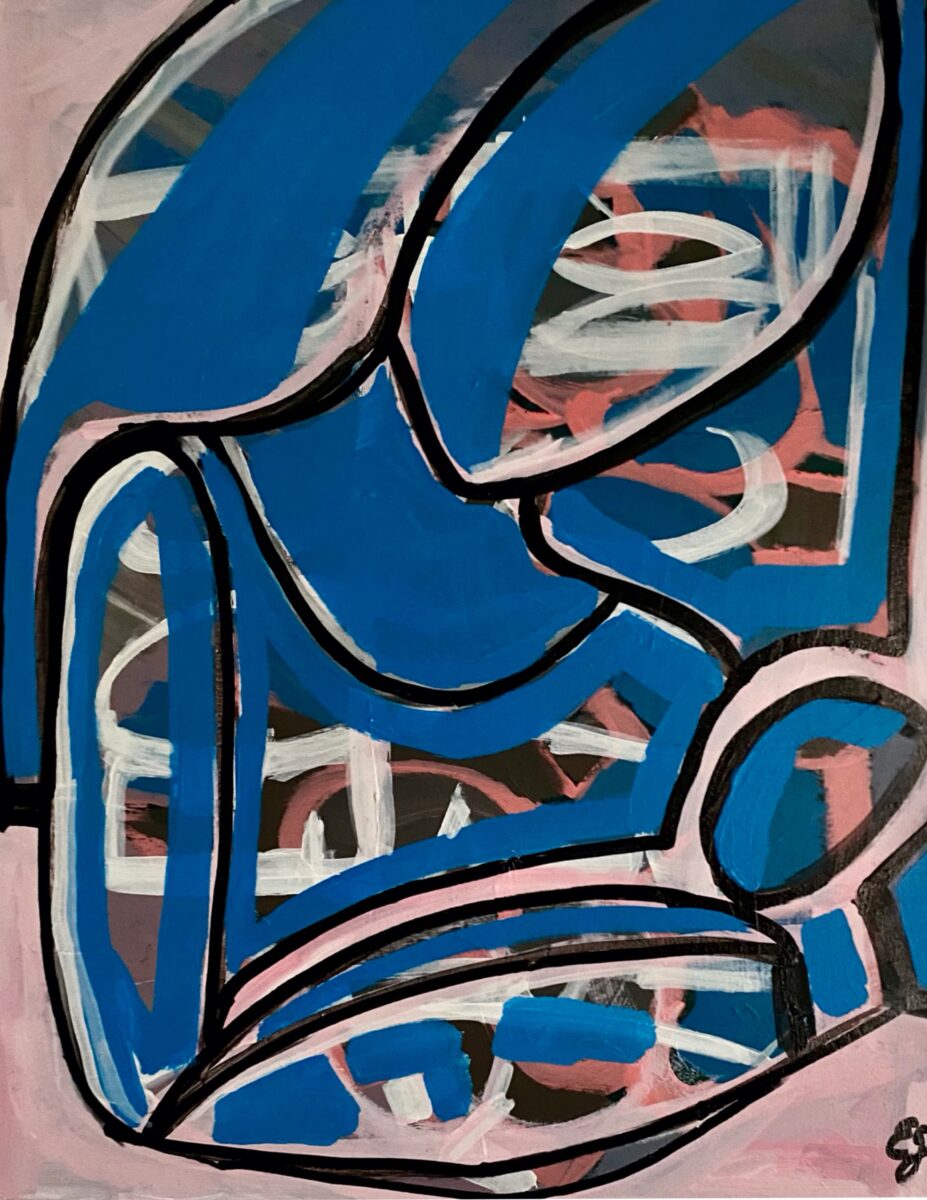

Erika Marie York’s painting All For You shares more than subject matter with Hedda Sterne’s second drawing: as in many paintings in this exhibit, we don’t see faces; the artist concentrates on feeling, not the details of appearance. But York’s depiction of feeling is unlike anyone else’s. In Sterne’s black-and-white drawing, the outline of the figure is everything. York’s outline—a few confident lines—serves only to tell us that we’re looking at a woman holding a baby in the crook of her arm. It’s a familiar subject and our culture tells us what such a woman feels—some kind of quiet joy. But in this painting, the peaceful blue of the woman’s body as a whole is almost violently interrupted here and there: we move into intensely colorful, apparently three-dimensional areas of wild feeling, in which brown is covered by streaks of pinkish orange, and that color sometimes by white. I think we’re meant to know that though she’s literally blue—except for those breakthrough areas—this is a Black woman. What she feels is a complicated, roiling mix. Excited white strokes are most numerous on her face. The baby’s belly also has the turbulence of those white lines, but the quietest spot in the painting is the baby’s head—some of it the bright color, some darker. The child, unquestioning, receives and calmly returns (we don’t see the face, but the baby’s pinkish-orange thoughts point upward) the mother’s intense gaze.

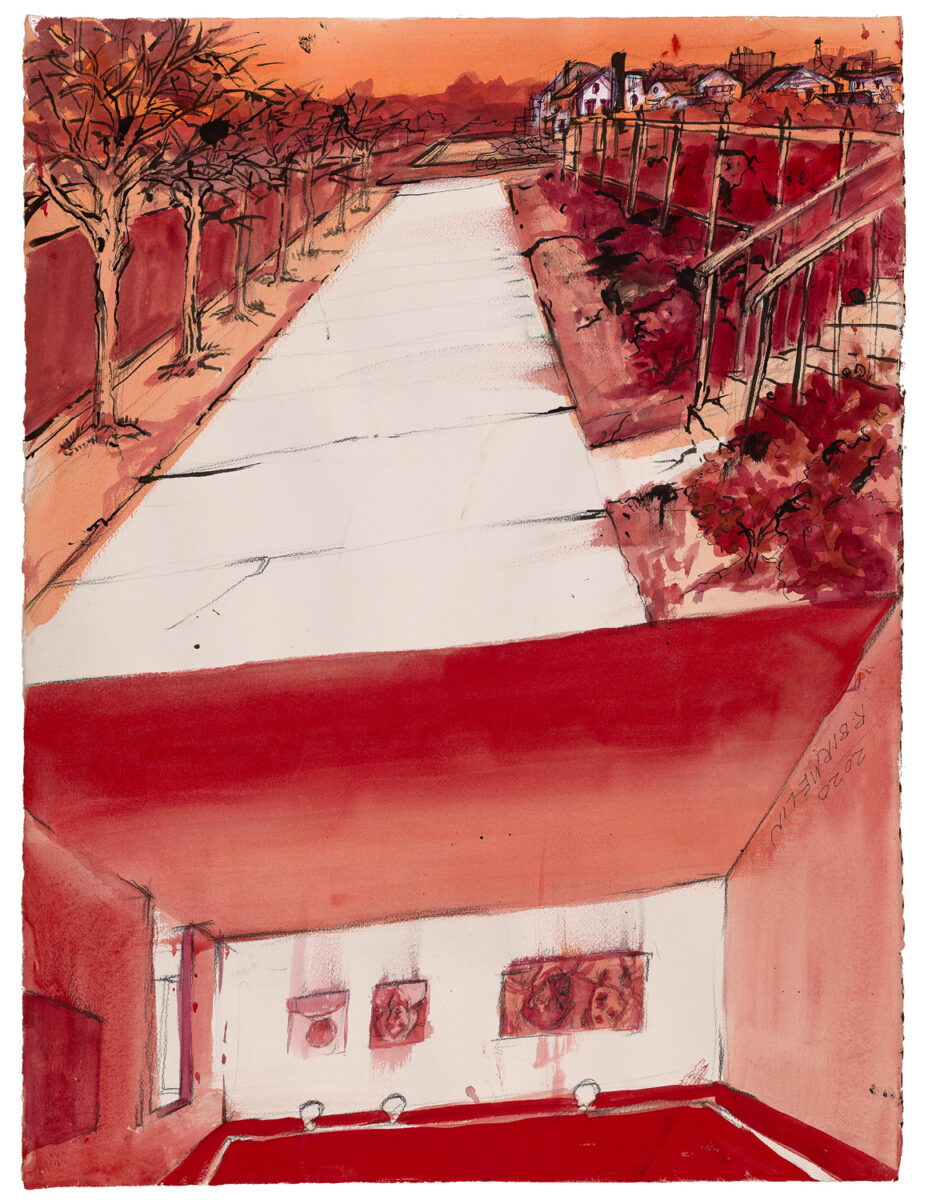

Robert Birmelin, over many decades, painted people in complicated urban situations: in The Lost White Dog, for example, people hurry up the steps of a subway station while a man reading the newspaper turns as if the viewer had asked him a question, all while a white dog passes by. Even in this painting before macular disease, what people are doing and how they feel matters more than the details of their appearance: the position of the body tells us whether someone is curious, hesitant, lost in thought. When Birmelin’s eyes changed, he didn’t lose all his central vision; his drawings in this show, made after the change—with a wash of red over them—have less detail, but that same precision about attitude and emotion—as in Hedda Sterne’s later drawing—as if he could see a body more easily than a face. Like some of Birmelin’s earlier work, one painting, Two in One—Sidewalk and Gallery, would be a different painting if you could turn it upside down: under a street lined with trees is a studio with drawings on a wall. Birmelin points out in a video on YouTube, Robert Birmelin’s Life in Art, that the street has no people walking on it because he now lives in a suburb rather than a crowded city; not all the changes in an artist’s work result from changes in vision.

Some of these artists continued to do something like what they’d done before: their hands knew how, whether they saw or not. In Moonlight on the Forest Floor by William Thon, broad brushstrokes are visible, a mountain is indicated by a bulky shape, and the forest floor, seen as a detail, might appear to be from an abstract painting. Thon’s earlier work is more delicate but also has trees in it, and is also about the nature of paint as much as about what it portrays. A’Dora Phillips tells us, in Beautiful in a New Way: The AMDF Collection of Works by Artists with Vision Loss, that Thon could hardly see, but knew what his hands needed to do. The shapes he’d made before—luckily—had not been precise, so the later paintings aren’t entirely different.

A film on the Vision & Art Project website demonstrates how Lennart Anderson managed vision loss. He had always painted what he saw. In the film he puts his face close to his subject, then close to the canvas. He measures to check on what he can’t see. His paintings are not intricately detailed but they are detailed; I wouldn’t have guessed that they were made by someone who didn’t see well. Spiderplant strikes me with the most force. The dark background is alive with different colors. It doesn’t matter exactly what is behind the plant, or under the table on which it sits; there’s no attempt here to reproduce the room. The painting has a kind of joy in melancholy. The dark swirls allow my flawed eye, at least, to stop trying to figure out what it’s seeing. This painting was made when Anderson had lost some vision but was not yet legally blind, while Antiope and Back View, Woman on a Box are from the time when he had no central vision at all. Yet those two paintings have clear lines, precise edges (though they also have that satisfying swirling background). There’s more defiance of macular disease in these two paintings than I might have imagined was possible. I wonder if Anderson himself was able to see them.

Robert Andrew Parker is another painter whose work changed minimally when his eyes changed. Speaking in a Vision & Art Project film of paintings he made after losing some eyesight, he says, “The pictures are always lopsided anyway. It’s not as if I’m a photorealist.” The implication is that it doesn’t matter when a painting was made. Parker admits that he can’t paint as precisely as he sometimes used to, but some of his early paintings are dark and fluid. An untitled picture of a monkey amid trees, and another of a monkey on a branch with the full moon behind it, have the softness and vulnerability that seem to come, for some artists, with loss of eyesight, yet they were painted before Parker had macular degeneration. The paintings from after his eyesight worsened, like Lincoln County, New Mexico and Edinburgh, are less detailed. Another, of a train heading for a tunnel, is almost abstract to my eyes; the train is barely sketched. Parker’s paintings were always playful, and playfulness remains, but his later work also suggests something sobering in what isn’t meticulously depicted, in what lies behind the painting.

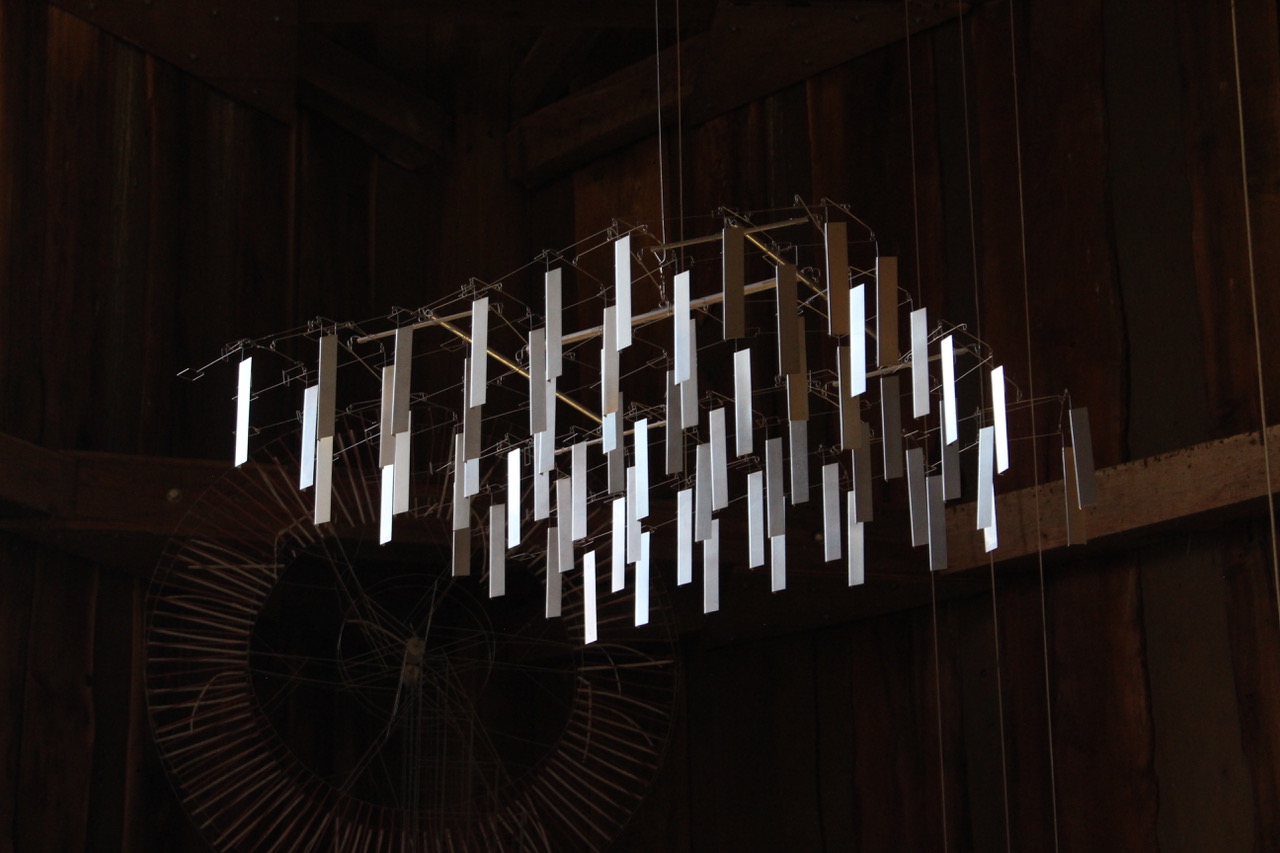

For a viewer with imperfect vision, sculpture is a particularly satisfying form of art. It’s three-dimensional, so there isn’t just one way to look at it, while the message implicit in some representational paintings is that if you can’t see that unmarred face or object—if your view is marred—you fail. But nobody sees all of a sculpture at once, so if you have to shift your gaze to see what’s a little to the side, that’s not a big deal. If you’re allowed to touch, even better. Tim Prentice’s sculpture moves, so no one, with any sort of vision, would miss what matters to him: how air, on its own, moves. Prentice told the Vision & Art Project that he wasn’t much aware of his diminished vision when he worked, because he could do most of what he wanted to do by feel. A viewer with diminished vision gets an invigorating sense of permission from Sammamish Study. I imagine the piece wouldn’t be very different if the artist had not developed eye problems: what’s tangible, here, matters more than what is seen.

After Philip Perkis lost some vision, as A’Dora Phillips explains in Beautiful in a New Way, he believed that his photographs were, in his words, “more abstract,” and “more akin to drawing.” One photograph in this show, Stony Point, from a time when he’d lost still more of his eyesight, is indeed abstract. He seems primarily interested in the look of the tree trunks that he photographs, the thickness and darkness of the lines. The photo might seem sadly simplified to someone with good eyesight; for me it’s a pleasure to look at the shapes, not to have to work out what the subject is. If your eyesight was so limited that you didn’t know it was a picture of tree trunks, you might still take pleasure in the solid, dark forms and their satisfying arrangement.

Dahlov Ipcar’s Leopard and Birds, from before she had eye problems, and Sunlight in Forest Glade, from after, are perhaps the works in this show most revelatory about what had changed and not changed for the artist. Both depict wild animals, obviously a preoccupation of Ipcar’s. They aren’t realistic in the early painting. A leopard, birds flying past it, and jungle plants around it are stylized, drawn and colored with perfect control, so the shapes make a kind of mosaic design, and, like something manufactured rather than painted, they have hard, firm edges and no shadows. The second painting is extremely different, but still of animals—deer, a tiger, a leopard, others I can’t identify— still moving through green vegetation. I guess she could no longer see enough to make those firm shapes. Yet, strangely, this painting is more realistic than the earlier one: the composition is abstract, but the animals look real, though only glimpsed, as they might be in life: suggestions of animals, as if by someone who isn’t sure what she just saw running past. Ipcar saw them clearly in her mind, and could still make her hand depict them. The depiction is honest about her eye trouble: she painted imaginary animals as if glimpsed by someone who doesn’t have time to take a good look—or by someone whose eyes are damaged.

Serge Hollerbach told The New York Times, in 2018, how his painting changed when his eyes changed: “To be playful, you have to have nothing to lose. Nothing to lose is a kind of new freedom.” It’s not hard to distinguish his later paintings in this show. Rather than showing specific shapes in distinct colors, with sharp edges, they take advantage of freedom from specificity, freedom from the sharp edge and the goal of being accurate about detail. The subject matter is unchanged: people in groups, people in cities, city buildings. But shape is more important here than detail. In two paintings of city buildings, the shapes have soft edges, and the details blur. They are less like depictions a builder might imitate, or a realtor look at for information, and more like representations of the human feeling of those inside, of uncertainty and yearning. People in other paintings are sketchy, though we sense their life—they are on their way somewhere, between one thing and another. Two abstract paintings are intensely emotional. Both Hollerbach and Birmelin use red a great deal, and I wonder if they saw it most easily; red is the easiest color for me to recognize. I wonder if some of these painters consciously chose to paint pictures that others with their disease could enjoy.

Almost all the artists in this exhibit, unfortunately, are white men. That’s surely because the show primarily looks at the past: nearly all these artists were born between 1906 and 1935, and took up their careers when that was less likely for women and people of color. Maybe macular degeneration, when artists in those categories developed it, was simply one problem too many for people trying to break into a field that didn’t welcome them. Or maybe more art exists by twentieth-century women and people of color with this condition, but a lack of professional connections at the time has so far made it impossible to find their work: it’s in a grandchild’s attic. Artists still develop macular degeneration, of course. Macular disease continues to affect the tiny spot in the center of the retina with which we see detail. Sometimes vision loss is slight; sometimes it results in legal blindness. But because treatments have improved for some forms of the disease, including those that do the most damage, life-changing vision loss is much less common than it used to be. The phenomenon documented in this show—artists whose macular degeneration makes a noticeable difference in their work—may be increasingly rare as scientists develop treatments for more and more forms of the disease.

Before I began having eye trouble, almost forty years ago, my favorite paintings were representational ones from the Renaissance and seventeenth century. After my symptoms started, I didn’t like them as much as before. Then, when my vision became a little worse, I lost much of photography; I could see photographs, but could no longer detect the subtleties that made them works of art. The first indication that my pleasure in some art would be even more intense than earlier came when I saw a maquette by the British sculptor Barbara Hepworth: a three-dimensional, abstract model for a piece she was planning. I am a novelist, and it seemed that this piece somehow had my next novel folded into it. The more I stared, the more I understood about what I’d be writing. Hepworth’s piece evoked complexity, mystery. And because it was sculpture, I didn’t need to stand squarely in front of it, conscious of what I no longer saw accurately. I moved from one side, to another, then around the back. Abstract art in general—anything that wasn’t representational—spoke to me now as nothing else had. I wasn’t comparing my view with what I knew I ought to see.

At that time one of my eyes had only subtle imperfections, though the other had almost no central vision. Eventually my good eye developed a noticeable blank. The larger it got, the more I needed to look at abstract art and, even more, expressionist art—paintings that represent something but make no effort at photographic accuracy, in which the accuracy is about feeling, which is expressed by means of brushstrokes or shapes or areas of color.

If everyone had macular degeneration, expressionist art—most of the art in this exhibit—would be considered realistic, or as realistic as any of us could get. Early in the period when my good eye started to develop gaps, I tried to find words for what I saw: “As I sit in the room where I work, objects look almost normal. But when I move my eye past the rectangular post at the top of the staircase, it doesn’t look like a solid, or like something drawn with straight lines. It seems soft, changing slightly as if it was made of light: a shadow that shifts when a breeze moves a curtain, or when a cloud crosses the sun. Objects are porous, slightly liquefied. . . . I might have been looking at forms reflected in a body of water.” Some artists in this exhibit depict what I see. I think the disease drew me to art like theirs, and I can’t help thinking that these artists found, as I found, that having the disease made art even more necessary than before. Macular degeneration, like expressionist art, simplifies what we see. The work of artists with macular degeneration says something about looking at shape, about giving up line and accuracy, about the vulnerability in what may appear to undamaged vision to be a solid and protective object, like a brick building. Or maybe it is our own vulnerability we become aware of: the softness of the edge is right for the experience of loss and incapacity.

Accident and chance can be helpful in making any art. I heard a musician explain the success of his recent songs: his studio was being renovated so he couldn’t get to the instruments he usually played. The imagination may be freed by the unexpected, even by unexpected difficulty—as long as there isn’t too much difficulty. At times, obviously, macular degeneration is simply devastating: an artist can’t work at all. But at other times, it can be managed, or it’s even stimulating. The artists in this show may have felt stymied by the challenges of decreased vision, but then tried something new. Maybe the newness—the very fact that they hadn’t chosen the method to suit the piece they wanted to make, but to enable them to make anything—contributed to the intensity, drama, and emotional power of the pieces in this exhibit.

Art is often a response to trouble, whether historical tragedy or personal loss; we wish the terrible thing hadn’t happened, but are glad to have the symphony or poem. When the art is visual and the trouble involves seeing, the results are especially poignant, but also momentous and meaningful. Seeing what artists have made after losing substantial vision—and how, in some cases, it differs from their earlier work—is a rare opportunity: this exhibit is a gift to anyone lucky enough to see it.

Alice Mattison is the author of seven novels, most recently Conscience, as well as four collections of stories and The Kite and the String: How to Write with Spontaneity and Control— and Live to Tell the Tale. Her stories, essays, and poems have appeared in The New Yorker, The Threepenny Review, Ploughshares, The Paris Review, and elsewhere.

Exhibition catalogs can be purchased on our benefit website, where you can also make donations and view and purchase artwork from the show.

Exhibition Details

Dates: March 20-April 26, 2024

Hours: Monday-Friday 10 AM-5 PM. Saturday-Sunday 10 AM-4 PM

Cocktail reception: Thursday April 4, 2024, 6-8 PM

Location: The National Arts Club, 15 Gramercy Park South, New York

More information: https://www.nationalartsclub.org/exhibitions

Online viewing room: https://visionartbenefit.org

Leave a Comment