Amazing Women Artists with Macular Degeneration

March 01, 2022

In honor of Women’s History Month, a look at eight amazing historical and contemporary women artists with macular degeneration.

GEORGIA O’KEEFFE (1887-1986)

From her origins on the Wisconsin plains to her death in the New Mexico desert, O’Keeffe’s life and work, which has had a monumental impact on American art, is frequently described as mythic.

She began her formal studies in 1905 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, then studied with William Merritt Chase at the Art Students League of New York.

In art school, she felt constrained by the pressure to “copy nature” and, early in her career, O’Keeffe began to work on a series of abstractions based on the ideas of Arthur Wesley Dow. Alfred Stieglitz exhibited these abstractions at his gallery, 291, in Manhattan, which launched O’Keeffe’s professional career. These abstractions were a kind of visual language O’Keeffe had discovered to express her unique truth about the world. They form the foundation of her later work, in which she explored the intersection of representation and abstraction in iconic paintings of flowers, trees, mountains, lakes, bones, and other natural forms.

Her paintings now grace the walls of most major museums.

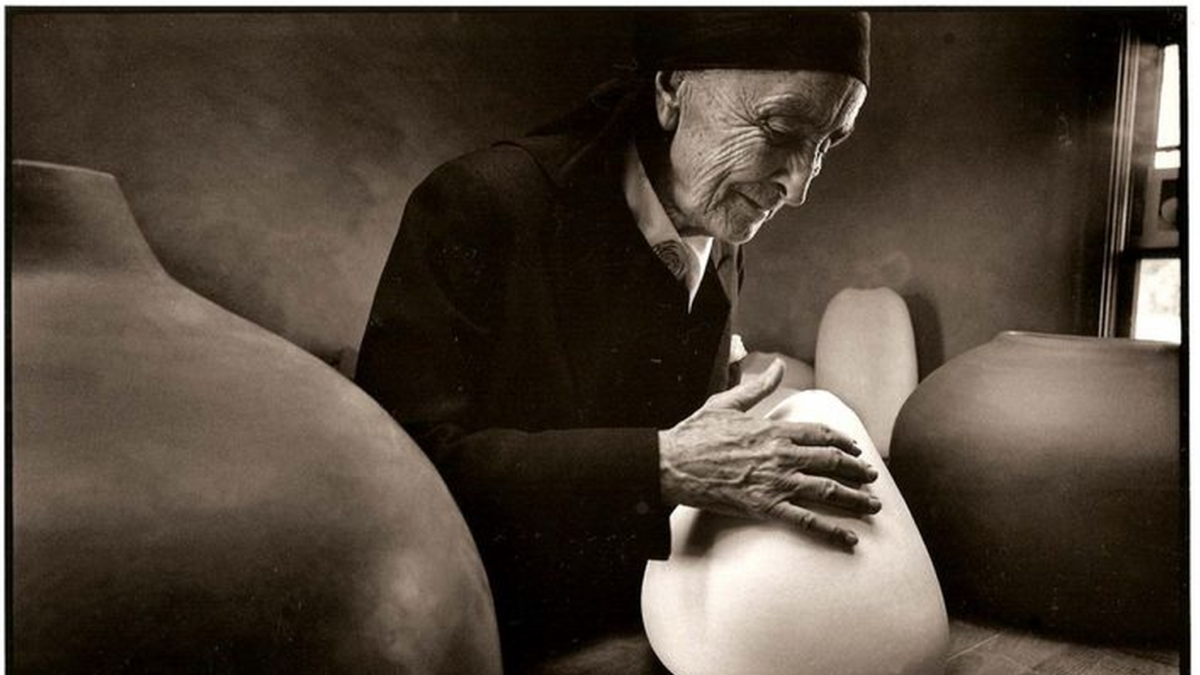

O’Keeffe’s post-macular artwork

O’Keeffe’s first signs of macular degeneration may have appeared as early as 1964. As Jeffrey Hogrefe relates in his biography of the artist, she “rounded a curve in the road she was driving from Ghost Ranch on a brilliantly sunny day… and the valley narrowed to a patch of greenery along the river. It felt, she said later, as if a cloud had entered her eyeballs.”

She finished her last unassisted oil paintings in 1972. In one, Black Rock with Blue Sky and White Clouds, a stone dominates the canvas, a sliver of blue sky and clouds behind it. In another, The Beyond, a wide band of darkness at the bottom of the canvas creeps toward the horizon line. Looking at it, one feels that all light will inevitably be engulfed. “My left eye has become much more cloudy,” she wrote in a letter that year, “and it’s as if my right eye is beginning to cloud. I assume I should know there is nothing that could be done about it. Am I correct?”

O’Keeffe sometimes elicited assistance from others when working on her canvases. The summer of 1976, for instance, she directed John Poling, then a handyman at Ghost Ranch, to execute her conception of several works, including From a Day with Juan. When he saw the painting published in ARTnews, he asked for credit. Though she advanced the claim that his “contribution had no artistic significance,” she stopped working with assistance after this event.

Her final works include abstract watercolors that look back to the abstractions she did in 1915-1918. In the last few years of her life, she also worked in clay. You can read more about her late work in the V&AP article about the recent retrospective in Paris of O’Keeffe’s work.

HEDDA STERNE (1910-2011)

Sterne’s early background and training

An imposing figure in Twentieth Century American art, Hedda Sterne was born Hedwig Lindenberg to Jewish parents in Bucharest in 1910. After showing an early interest in drawing, Sterne received private art lessons as a child.

Along with art, Sterne was tutored at home in languages and classic literary texts, many of which she read in their original languages. As a young woman, she traveled frequently to Vienna and Paris, where she attended classes at the ateliers of Ferdinand Léger and Andre Lhote. In 1929, she began formal studies in art history and philosophy at the University of Bucharest (she was never to complete them). Her profound early education and cosmopolitan upbringing provided the foundation for a life-long exploration of the arts, literature, and philosophy in her thinking and artmaking.

Sterne’s received her first international recognition when her collages were included in an important 1938 group exhibition in Paris.

Sterne’s career as a refugee artist in NYC

After fleeing to the United States in October 1941, Sterne met her second husband, the fellow Romanian artist and refugee, Saul Steinberg. She also became involved with the circle of New York School artists with whom she is often associated. In spite of this association, however, she worked with a myriad of materials and styles over the years to create paintings and drawings that often defy categorization.

Sterne exhibited in dozens of solo and important group exhibitions, including in four decades of shows at Betty Parsons Gallery. Her work is in the permanent collections of major museums, such as the Museum of Modern Art, The Whitney Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The sole woman in the famous 1951 Life Magazine photo, “The Irascibles,” she was the subject of two major retrospectives: at the Montclair Art Museum in 1977 and at the Krannert Art Museum (the University of Illinois, Champaign) in 2006.

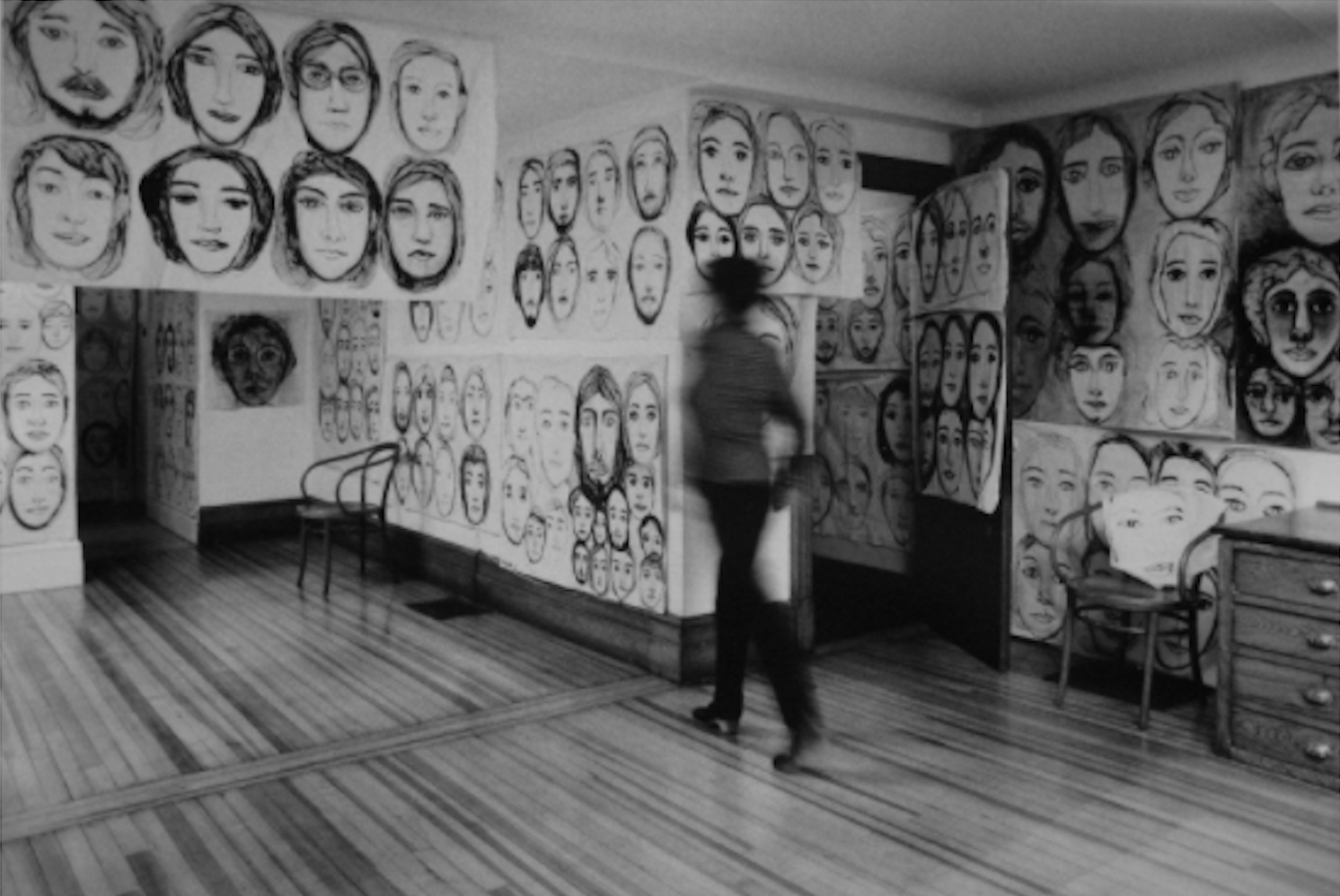

Sterne’s post-macular artwork

By the time Sterne was 83, she experienced vision loss from macular degeneration. Within a few years, she could no longer see well enough to paint and began to draw exclusively. She worked monochromatically with pencil, watercolor, wax crayon, pastels, and white-out on white paper. Many of her drawings can be read as heads and interpretations of subjects from nature such as insects and trees. Some of her last drawings she called “ghosts.”

These late drawings are considered to be among her finest works. They are in several important museums, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Berkeley Art Museum.

Lawrence Rinder, who visited Stene in her studio many times between 2001 and 2004, describes how these works were made:

I don’t recall her speaking about [her vision loss] much, but it does seem clear that she had the capacity to continue “seeing” even with low-sightedness. That is, she “saw” things beyond the field of vision, observing fundamental structures and dynamics of being. What is remarkable is that she was able to create images of these “visions.” Her ability to compose images must have come from her memory (perhaps kinesthetic memory) of form.

Sterne had a stroke in 2004 and stopped working altogether. However, in a 2009 interview, she said that she was still drawing, in her head.

You can read more about Sterne’s last years in our article about the books she read after experiencing vision loss.

DAHLOV IPCAR (1917-2017)

Dahlov Ipcar was born in Windsor, Vermont, to artists William Zorach and Marguerite Thompson Zorach. She grew up in Greenwich Village. Shortly after marrying as a young woman, she moved to Maine, where she lived for the rest of her life. Ipcar was not formally trained in art, but she was mentored by her parents, who encouraged her to paint from an early age.

In 1939, Ipcar was the first woman ever to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition, called Creative Growth: Childhood to Maturity, featured work Ipcar had done between the ages of 3 and 22. It was the inaugural exhibition in a special space at MoMA called the Young People’s Gallery. For the next decade, she completed several WPA murals and continued to show her work in New York. Eventually, however, she retreated from the pressure of exhibiting her work in New York.

In the relative isolation of Maine, she discovered an approach to painting that she termed “non-intellectual cubism.” Painting highly stylized animals from memory and imagination against prismatic background shapes created an effect, she felt, that was true to the real without being slavishly realistic.

Although Ipcar is best known for her intricate and highly imaginative oil paintings, she also wrote and illustrated books and produced fabric collages, hooked rugs, needlepoint tapestries, and soft sculptures.

Among other institutions, her work is in the permanent collections of the Brooklyn Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Ipcar’s post-macular artwork

For many years, Ipcar had a mild case of macular degeneration that she kept private. In 2015, however, she suffered a precipitous decline in her eyesight and could no longer finish paintings in her former manner. The unfinished paintings she produced at this time reveal her unique mastery and insight of composition through color and shape.

Ipcar saw these paintings as failures and at first feared her career as a practicing artist was over. But after a period of adjustment, she began to produce a new body of work. She relied on muscle memory, including a kinesthetic memory of form, to draw animals with bold lines on large sheets of paper, which she then used as the basis for assisted paintings. In one of her last interviews, she explained that her hand, which “knew a lot,” made these works possible.

In one of the last interviews she gave before she passed, Ipcar talked with the V&AP about her vision loss and long career.

AGNES VARDA (1928-2019)

Agnès Varda was a French film director, photographer, and visual artist. She was born Arlette Varda in Belgium to a French mother and a Greek father. Shortly before Brussels surrendered to German forces during World War II (May 28, 1940), she and her family fled to France. At first, they lived on a boat in her mother’s hometown of Sète. Before the war ended, they moved to Paris.

When Varda was 18, she changed her name to Agnès. She received a degree in literature and psychology from the Sorbonne, where she studied with Gaston Bachelard (whose ideas, she says, she didn’t always understand). Intending to become a museum curator, she took classes in art history at the École du Louvre. Yet she was not entirely sure of her way forward and, as she recounted, “ran away” to Corsica without telling anyone.” She spent three months working on fishing boats, during which time she decided to become a photographer.

Varda’s first career as a photographer

She enrolled at the Vaugirard School of Photography. Almost immediately, she began to earn a living taking pictures of families and special events. Along with plying her trade as a professional photographer, Varda explored its artistic and creative potential. When her friend Jean Vilar opened Théâtre Nationale Populaire, she became its official photographer. She held this position for 10 years, from 1951 to 1961, during which time she received increasing recognition as a photographer.

Varda’s second career as a filmmaker

As Varda was building her career as a photographer, she made her first film, La Pointe Courte, in 1955. Then 27, Varda describes writing a script seemingly out of nowhere because she “wanted words”. She’d not seen more than ten films at that point in her life. Nor had she studied filmmaking, or, as was customary, served as an assistant in the industry. Yet, defying all expectation, she shot her first film.

Over the next 64 years, Varda went on to make many more films. Some were fictions and some were documentaries. However, as in La Pointe Courte, there was always an evocation of the “real” in her fictions and a fanciful element in her nonfictions.

Her works are incredibly diverse in their subject matter and approach. However, throughout her career, she was concerned with the lives of women and the disenfranchised, with time and the cultural moment, and with reality and representation.

Varda’s post-macular work as a filmmaker and visual artist

Varda experienced vision loss from macular degeneration about 15 years before she passed away. Her loss of vision corresponded to what she called her “third life,” when, as she used to say, she “changed from an old filmmaker into a young visual artist.”

Her first exhibition as a late-life visual artist, Patatutopia, was in 2003 at the Venice Biennale. In the following years, Varda developed 40 exhibitions that often involved “recycling” her former work in startlingly inventive ways.

At the same time, with the help of her daughter, Rosalie Varda, she made a number of critically acclaimed autobiographical films while suffering from vision loss. These included The Beaches of Agnès (2008), Faces Places (co-directed with JR, 2017), and Varda by Agnès (2019).

DORIS SALCEDO (b. 1958)

Doris Salcedo was born in Bogotá, Colombia. She studied at Jorge Tadeo Lozano University and New York University before returning to Bogotá, where she continues to live and work. Her sculptures and public installations are in response to political violence. Until recently, her work was primarily concerned with the more than 90,000 Colombians who have disappeared in the past fifty years, 70,000 of them without a trace. In recent years, some of her sculptures and installations have included victims of corruption, displacement, and injustice beyond Colombia.

An artist associated with the White Cube Gallery in London, she has had solo exhibitions at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Madrid), Harvard Art Museums, Nasher Sculpture Center (Dallas), Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Guggenheim Museum, Pérez Art Museum (Miami), Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (Mexico), Tate Modern, and New Museum (New York), among others. She has been the recipient of many awards, including the Nomura Award, the world’s largest art prize.

Salcedo’s vision loss

Salcedo has had Stargardt disease since early in her career and is now legally blind. She does not find this an impediment to her art in any way. As she said in a 2017 interview with The Vision & Art Project: “I think it is important to say that for me art is a way of thinking, and in order to think you do not have to have perfect vision. For me art is an attempt to comprehend reality. Art is a way to expand the narrow definitions we have of what it means to be human.”

ANDREA TORRICE (b. 1955)

A filmmaker, Andrea Torrice was born in 1955 in New York City to parents who had rebelled against the conventions of their upbringings to become artists (her mother a painter, her father a jazz musician). She spent the first years of her life in Manhattan and Queens before her family moved to New Jersey.

She studied modern dance at NYU and creative writing and literature at SUNY Purchase. While at SUNY, she realized she had an interest in visual storytelling. She moved to the Bay Area, which had a vibrant filmmaking community, began studying filmmaking, and became involved with a community of people who were making various sorts of films. While taking graduate classes at San Francisco State University, she got an internship at the local PBS station.

Torrice’s early-onset macular degeneration

At the age of 26, just as she was poised to take her first professional job in film, Torrice was diagnosed with Stargardt disease. Subsequently, her career was on hold for about eight years while she learned adaptive technologies and rebuilt her life.

Eventually, after getting support and rehabilitation training, she returned to film. Her first major project was a commissioned work, Forsaken Cries: The Story of Rwanda (1997), which focused on how Rwanda’s colonial period contributed to the genocide there in 1997. Not long afterwards, she completed a project she had conceived on her own, Rising Waters: Global Warming and the Fate of the Pacific Islands (2000). This documentary was one of the first to examine the issue of global warming and the impact it would have on the people, cultures, and ecosystems of those islands.

Torrice has since made many more documentaries, some of them commissioned, which engage complex environmental and social issues.

In a 2018 oral history with the Vision & Art Project, Torrice explained how she works with low vision. She storyboards her ideas on large pieces of newsprint paper she tapes to the walls. Instead of focusing on special details, she composes shots more abstractly, focusing on line, movement, composition, and color as opposed to a singular object or scene. Sound and music are as vital to her work as visual images are. While she herself focuses on a film’s story, ideas, and structure, she relies on skilled craftspeople to do such things as the camera work and editing. She feels low vision has given her the ability to see things as an interconnected whole.

JEN OLDKNOW (b. 1975)

Born in Lincolnshire, England, Oldknow’s childhood was spent in a rural environment which sparked a passion for the landscape and the natural world. This has always been the primary inspiration on her art.

She now lives in Derbyshire, in the heart of England, with a studio on the doorstep of the stunning Peak District National Park. Daily walks in the countryside with her dog and sketchbook provide a rich source of subject material.

Oldknow’s early onset macular degeneration

Since being diagnosed with early onset macular degeneration in her twenties, Oldknow’s work has gradually evolved, and continues to do so, as she deals with the changes to her vision. This includes using jet black ink when drawing to make dark bold marks in contrast to the paper, and a move to creating more abstract compositions using the malleable and tactile qualities of oil paint.

Oldknow’s professional success has taken place post-macular degeneration. She exhibits her work across the world and has won numerous awards, including at the National Exhibition of Wildlife Art, The Royal Birmingham Society of Artists, the Association of Animal Artists and the Society of Wildlife Artists at the Mall Galleries in London. These awards span across a range of subjects and media, including watercolor, drawing and printmaking.

You can read more about Oldknow in our 2016 interview with the artist.

ERIKA MARIE YORK (b. 1990)

York’s early vision loss

Born in Washington, D.C. to artist parents, Erika Marie York was in elementary school when she began to lose her vision to Stargardt disease. With her parents’ encouragement, she took art classes and workshops when she was growing up. She credits this experience with giving her confidence in her ability to make art in spite of a vision impairment.

York invested herself in becoming an artist after graduating from Smith College with a sociology degree in 2012. The Columbia Lighthouse for the Blind and H-Space Gallery in Washington DC have exhibited her work.

York feels that art has to do with sharing one’s perspective, which isn’t dependent on perfect vision. Largely shaped by her eye condition, her distinctive painting style—which includes large canvases, bold lines, bright colors, and figures often lacking facial features or wearing glasses—is inspired by what she sees.

You can read more about York here.

Further Reading

Doris Salcedo

Art Inhabits the Terrain of the Paradoxical

On the occasion of her exhibition at Harvard Art Museums, an interview with Doris Salcedo on vision loss and artmaking.

Read More

Leave a Comment