Agnès Varda’s Boundless Creative Vision

July 29, 2021

The Criterion Collection brought out The Complete Films of Agnès Varda in August 2020. The 15-disc Blu-ray box set includes twenty-one of Varda’s 24 feature films and 16 of her 22 shorts. The box set also contains extensive special features. I’ve spent the past year watching nearly every film in the collection. To help you figure out where to start with Agnès Varda, here’s a brief overview of her career and my viewing recommendations.

An Overview of Agnès Varda’s Career

The “Mother” of the French New Wave

Agnès Varda (1928–2019) defied all expectations when she made her first film, La Pointe Courte, in 1955. Then 27, Varda, who had studied philosophy and art history, was building a career as a photographer when she wrote a script seemingly out of nowhere. She’d seen no more than 10 films at that point in her life, hadn’t studied filmmaking, and hadn’t, as was customary, served as an assistant in the industry. Nonetheless, she shot her first film.

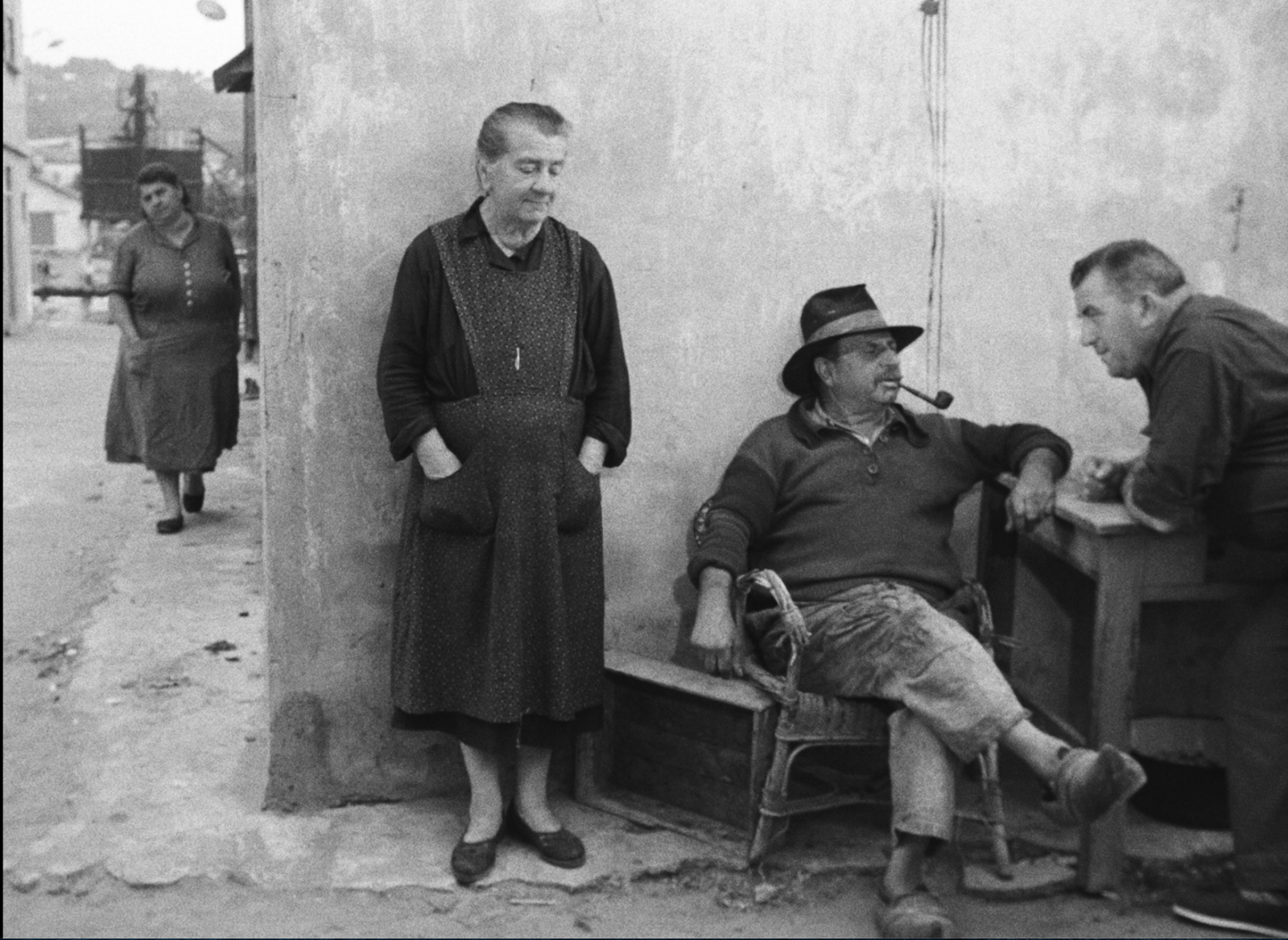

This film likewise broke many of the rules and conventions of filmmaking. Its structure, based on that of William Faulkner’s novel The Wild Palms, juxtaposes two story lines. The story lines, which have nothing in common except that they are set in the same place, run parallel to each other. One, purely fictional, focuses on a married couple. Their relationship has reached a point of inflection. The man has returned to the neighborhood where he grew up, La Pointe Courte, in the town of Sète. (Varda knew Sète well, since her family took refuge there during World War II.) His wife joins him from Paris. They wander around La Pointe Courte and talk about whether to break up.

In the spirit of Italian neorealism, the other story documents the travails, daily life, and rituals of the community. A government official hounds the local fishermen. Women undertake the repetitive work of maintaining a family. A child dies. A marriage unfolds.

Professional actors present the first story in a self-consciously theatrical mode. Locals with no training in acting present the second story. Thus, Varda created an utterly unique film that exemplified many of the characteristics of New Wave cinema. These included location shooting, de-emphasized plot, autobiographical inflection, long takes, and a general spirit of experimentation. She did so three years before Claude Chabrol made what some consider to be the first French New Wave film, Le Beau Serge. As a result, Varda is often called the “Mother” or “Grandmother” or “Godmother” of the French New Wave.

Agnès Varda’s “real” fictions and fanciful documentaries

Over the next 64 years, Varda made many more films. Some were fictions and some were documentaries. However, as in La Pointe Courte, there was always an evocation of the “real” in her fictions and a fanciful element in her nonfictions.

Perhaps by nature Varda was a bit of a rebel. None of her films, not even the most commercially successful of them, ever conformed to industry expectations or duplicated the form of another. In interviews and lectures she gave about her work, she talked about how she always started with a “point of view.”. She believed that every story required its own unique structure and typically worked that out before launching a project.

For Varda, the “writing” of a film went beyond its screenplay. It included all the decisions involved with creating a singular cinematic composition—the shooting script, lighting, music, casting, camera movements, etc. To encompass all these aspects, she coined the term “cinécriture” (cine-writing). Working within constraints—internal ones involving a film’s meaning and structure, external ones often involving budgetary concerns—Varda’s uniquely individual oeuvre is always personal. Personal in the sense that you feel the mind and ethics of the auteur in each of her pieces. And yet, within that multitude is a continuity of interests.

Agnès Varda‘s preoccupations: women, time, social justice, seeing deeply

In one of Varda’s late films, The Beaches of Agnès, she says that if you opened her up, you’d find beaches.

Open up her films, and you’ll find women. Cléo in Cléo from 5 to 7, who in the course of two hours, while waiting for the results of a biopsy, is transformed from one who is looked at to one who looks (and sees). Thérèse and Émilie of Le Bonheur, who double one another and serve as interchangeable cogs in the machine of a man’s happiness. Pauline and Suzanne of One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, two very different women united in sisterly solidarity. Mona of Vagabond, dirty, smelly, and unlikable, a doomed rebel. And Agnès herself, who in her last films, turned the camera on herself.

Open up her films, and you’ll also find some of the most beautiful portraits of the contemporary age. Her gaze, and the camera, linger for long seconds on the human face. In so doing, she shows it to be a poignant document of time.

Open up her films, and you’ll find a plethora of difficult social issues, no less with us today than they were in the shifting eras in which Varda worked. At the core of Varda’s complex, multivocal vision is the question of how to not only survive but thrive and enjoy life. That is true whether she is focusing on women’s struggle for selfhood, Black Americans’ struggle for equality, the artist’s struggle to be heard, or the plight of the disenfranchised in a culture of excess.

Finally, when you open up her films, you’ll find a long meditation on seeing. Her preoccupation with the subject reaches its apex with Faces Places (co-directed with the French photographer and street artist JR). When making the film, Varda had macular degeneration. Her vision—and seeing, more generally—is one of the film’s explicit subjects.

Agnès Varda’s Complete Films: where to start?

Amazingly, Varda’s entire life work fits into a compact Criterion Collection boxed set. That’s one of the miracles of film in the digital age. What once required a storeroom now weighs “200 grams dematerialized,” as Varda said. More than 50 years of work can be tucked like a book under one’s arm. (A miracle she acknowledges in one of her late-life art projects, when she built “Cinema Shacks” out of her old 35-mm reels.)

If you’re wondering where to start, put the six Varda films from BBC Culture’s “The 100 greatest films directed by women” on your list. These include: Cléo from 5 to 7, Vagabond, Le Bonheur, The Gleaners and I, One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, and The Beaches of Agnès.

To these, I’d add her feature-length films Documenteur, Jacquot de Nantes and Faces Places. Her short films Black Panthers and L’Opéra-Mouffe are also essential viewing.

One of the striking aspects of Varda’s work is the way it captures time. So I’d suggest going back to 1962 and, starting with Cléo from 5 to 7, traveling through time with her.

If you become as enamored with Varda as I am, return to the beginning when you reach the end. La Pointe Courte (1955) will be all the more meaningful in the context of her other achievements. So will the short films on this list. And remember, this is just a start. Beyond these films is a treasure trove of others. They’re all worth watching.

Agnès Varda’s Feature Films

Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962)

Though only her second film, Cléo from 5 to 7 is commonly considered Varda’s legacy-defining work. It’s about two transformative hours in the life of a Parisian singer, played by Corrine Marchand. At the beginning, she visits a tarot card reader who foretells her death. At the end she visits a doctor who diagnoses her cancer.

As Varda explained in her last film, Varda par Agnès—her autobiographical, auto-critical look back on her career—Cléo’s structure was inspired by constraint. The film had to be made cheaply in black and white. Varda thus envisioned a compact story shot in real time about a woman whose time is running out.

We follow Cléo seemingly step-by-step as she descends the stairs of the tarot card reader’s apartment building. She stops in a café, takes a taxi to her apartment. She seeks (and fails to elicit) sympathy from her housekeeper and lover. Her songwriter (played by Michel Legrand, who also scored the film) and accompanist arrive. They cheer her up and have her sing a new song. Its melancholy lyrics strike too close to home for Cléo to bear. In a rage, she ends the rehearsal, removes her wig, dons a black dress and hat, and goes out alone. While waiting for her appointment with her doctor, she wanders around Paris. She meets the sympathetic Antoine, a young soldier on leave from the war in Algeria.

In the first half of the film, Cléo, understandably, is worried and seeking solace. She is also somewhat capricious and fixated on her own beauty. In the second half of the film, Cléo awakes from her narcissistic enchantment. This allows her to forge more genuine connections with herself and others, as represented by her caring relationship with Antoine.

Le Bonheur (Happiness) (1965)

This may be Varda’s most haunting film.

François, a carpenter in his uncle’s shop, is married to Thérèse, a dressmaker. They have two children, a boy and a girl. It’s a lovely family. They exist in an idyllic, highly chromatic wash of harmony and domestic ritual, which includes weekend picnics in the country.

Then François meets a beautiful postal clerk, Émilie, who resembles Thérèse. François and Émilie fall in love and have an affair. This love does not displace his love for his wife or otherwise affect his life with her. Indeed, François believes his feelings for the postal clerk only add to the prevailing happiness of his life.

On one of their weekend excursions to the country, François tells his wife about his affair. She is clearly hurt, but almost immediately seems to “come around” and accept the situation. After his confession, François takes his usual nap in the woods. When he wakes up, Thérèse, who would normally be next to him, is gone. He rustles up the children and wanders off in search of her. When she doesn’t at first turn up, he grows more frantic. For good reason, since while he was sleeping she has drowned. Varda leaves it ambiguous whether she’s died by accident or suicide. He’s devastated. To convey François’s devastation, Varda repeats the scene of his finding his wife’s body several times. There’s a funeral. A bit of time passes.

Then, the idyllic life depicted at the beginning of the film begins again: the pleasant daily rituals of family life; the amiable interactions during the workday at the carpentry shop; the weekend picnics in the country. Except that the postal clerk, Émilie, has taken Thérèse’s place. It’s as if nothing has been lost at all.

One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977)

Set against the backdrop of the women’s movement in France, One Sings is about the friendship between two very different women. It transpires over the course of about fifteen years and includes more “plot” than Varda’s other films.

The film opens in the early 1960s. Pauline, a privileged young woman, is awake to the disadvantages of being the second sex. She lives with her traditionally-minded parents and is studying for her baccalaureate but wants to become a singer. In contrast, Suzanne is in love with a married photographer and lives in poverty with their two illegitimate children. When Pauline discovers that Suzanne is pregnant with her third child, she gives her the money to get an abortion. Shortly afterward, Suzanne’s lover hangs himself.

With no skills to support herself, Suzanne returns with her two children to her parents’ farm. They judge her, treat her with disdain. Pauline, meanwhile, rebels, leaves home, and forges a career as a singer. After losing touch with one another, the two women reunite 10 years later at an abortion rights demonstration. Pauline now goes by the name of Pomme (Apple). Suzanne is supporting herself and her children as a family planning counselor in the South of France. As each goes her own way again, they communicate their experiences in the postcards they exchange.

In Varda by Agnès, Varda said this film came out of her commitment to “women’s liberation, especially issues involving women’s own bodies.” Though it clearly has a message, it doesn’t feel didactic. Varda said this was because she buried the film’s thesis in the lyrics of songs. But it’s also because of the luminous quality of Suzanne and Pauline’s friendship, a subject so seldom captured in film.

Documenteur: An Emotion Story (1981)

Many of the murals in Varda’s documentary Mur Murs appear as a backdrop to Varda’s fictional film, Documenteur, which Varda made as a companion piece to Mur Murs (both films, however, stand on their own). In Varda par Agnès, Varda said Documenteur was the story of introverted Los Angeles. Anyone who has struggled to make ends meet in a large city, who has tried to find an affordable apartment, has silently waited at a laundromat, wandered the streets on their time off searching for cheap pastimes, suffered a loss and needed to keep those feelings to themselves as they’ve watched the rest of the world circle around them will identify with the emotional sensibility of this film.

Émilie (played by Varda’s editor Sabine Mamou) has broken up with her partner. She is trying to build a new life for herself and her son (played by Varda’s son, Mathieu Demy). We watch Émilie, as one day folds into another. She works at a desk that faces the Pacific Ocean, searches for an affordable apartment, hangs out with her son. Dialogue is spare, and the plot is minimal. Yet with these sparse happenings, the film creates a breathtakingly accurate portrait of loss. The one person with whom Émilie has an abiding connection is her son. Because he’s only a child she can’t talk to him about her grief. She thus exists in a vacuum of profound loneliness.

Vagabond (1985)

In nearly every film Varda made, she was preoccupied with the plight of outsiders, loners, and the disenfranchised. Usually, the serious subject matter was leavened by play, humor, a joie-de-vivre (even wacky) spirit of exploration and experimentation.

Not so her story about Mona, an “enraged loner,” as Varda characterized her in Varda by Agnès. The film starts at the end of Mona’s journey, when a farmer finds her frozen body in a field. Thus the question is not what will happen to Mona. It is, rather, what “the last weeks of her last winter” were like.

To find out, the narrator, who enters the film in a voice-over delivered by Varda herself, seeks out the testimony of the people who met Mona during her travels. Nearly all of them were played by non-professional actors and coached before giving their scripted, documentary-style monologues in front of the camera. What unfolds is a painful look into the increasingly bleak descent of a rebellious “vagrant,” as Mona is called. She was someone who elicited almost no empathy from the people she encountered.

As a Norton lecturer at Harvard in 2018, Varda discussed Vagabond’s “precise” and intricate structure at length. Courtesy of the Harvard Film Archive, you can access her talk here.

Jacquot de Nantes (1991)

This tender film is a portrait of and love song to fellow filmmaker Jacques Demy, Varda’s dearly departed husband. While she was making it, he was ill (he died only a few weeks after she finished filming).

It braids together three distinct narratives. One—what is arguably the dominant narrative—is a coming-of age tale, set against the backdrop of World War II. It follows Jacquot Demy, son of a car mechanic, as he becomes Jacques Demy, a filmmaking student in Paris destined to create several cinematic masterpieces. This strand of the film is based on the memoir Jacques Demy was writing at the end of his life. Varda suggested he turn his writings into a film. He said he didn’t have the energy and asked her to do so instead. To evoke the past, Varda shot this part of the film in black and white. She also filmed some of the scenes in what had been Jacques Demy’s father’s garage in Nantes.

In the second strand of the film, Varda explores the interrelationship between Demy’s lived experiences and some of his movie’s most well-known scenes. Passages from Demy’s movies, brilliantly shot in color, are spliced into the black and white dramatization of his childhood.

In the third strand of the movie, Varda works to capture the materiality of her husband’s presence before he passes. The camera travels heartbreakingly close along Demy’s skin, hair, eyes. It pulls back to linger on his face, his smile. The passages are shot in faint, watercolor-like tones. Next to the black-and-white coming-of-age story and the brilliant saturation of Demy’s films, it presents a third color palette, one that evokes the ephemerality of her husband’s life.

Together, the storylines point to mystery—the mystery of destiny, of creation, of love, and of death.

The Gleaners and I (2000)

One of the many interesting things Varda says in Varda by Agnès is that “Nothing is banal if you film people with empathy and love. If you find them extraordinary, as I did.” This deeply humane approach to her subjects is especially apparent in Varda’s documentaries. It’s the explicit point-of-view in The Gleaners and I, Varda’s incredibly moving film about modern-day gleaners in France.

Gleaning means stooping to gather the leftovers of a harvest. It has a long history in France, as evidenced by its appearance as a frequent subject in French painting and centuries-long presence as an adjudicated issue in French law. After noticing gleaners salvaging discarded food in Paris, Varda becomes fascinated by the subject. She sets out on a series of road trips around France to document the waste—and need—in a culture of excess. In so doing, she draws connections between the gleaners she meets and her own work as a filmmaker and artist. Ultimately, she understands herself to be one who gleans.

In making this film, Varda also discovers the cast-off, heart-shaped potatoes that she saw as emblematic of her inner being. They became a subject when she changed direction late in life and began making art installations.

The Beaches of Agnès (2008)

When Varda turned 80, she says she panicked. As a result, she looked back on her life and made this cinematic memoir. She’d begun revealing aspects of her own life in films and video installations beginning with The Gleaners and I. But in The Beaches of Agnès she actually made herself—or appeared to make herself—the central subject.

If you’re anything like me, by the time you’ve watched her previous films, you’ll want to know more about Varda. What mix of influences, life experiences, temperament, and education led to her visionary oeuvre? While this question may ultimately be unanswerable, Varda seems to anticipate and accept our curiosity and takes us on a journey through her life. But this is no straightforward recounting.

In the spirit of many of her other films, The Beaches is somewhat digressive (to allow herself to digress was a “freedom” she exercised as a filmmaker, she said). At the same time, it has a structural “spine.” Varda’s reminiscences radiate outward from the beaches where the most meaningful experiences of her life, both personally and professionally, played out. These beaches, she tells us, also constitute the landscape of her interior self.

She returns in person to each of these beaches. She talks about what she remembers of the time she spent on each. Sometimes, footage from her former films or one of the many events she’s participated in intrudes on the here-and-now, replacing contemporary reality. Other times, as the 80-year-old Varda reminisces, a younger version of herself, played by an actor, shadows her. As the many mirrors set up on a beach at the beginning of the film herald—with beachcombers, the sea, and Varda’s work endlessly reflecting an endlessly recombining scene— The Beaches of Agnès becomes a profound, multilayered meditation on reality and its representation.

Faces Places (2017)

In this film, Varda and her co-director, JR, take a series of road trips around France. They want to shine the light on ordinary people. They do this by taking pictures of the people they meet, which they then blow up to paste on the facades of various community structures, including abandoned houses, the sides of shops and ships, barns, water towers, passageways.

As their friendship deepens, however, their excursions undergo a change. JR asks Varda to help him choose an image to paste on the side of a massive World War II German blockhouse, a project he’s long wanted to undertake. Varda takes JR to meet her friend Jean-Luc Godard. (To her sorrow, they are turned away.)

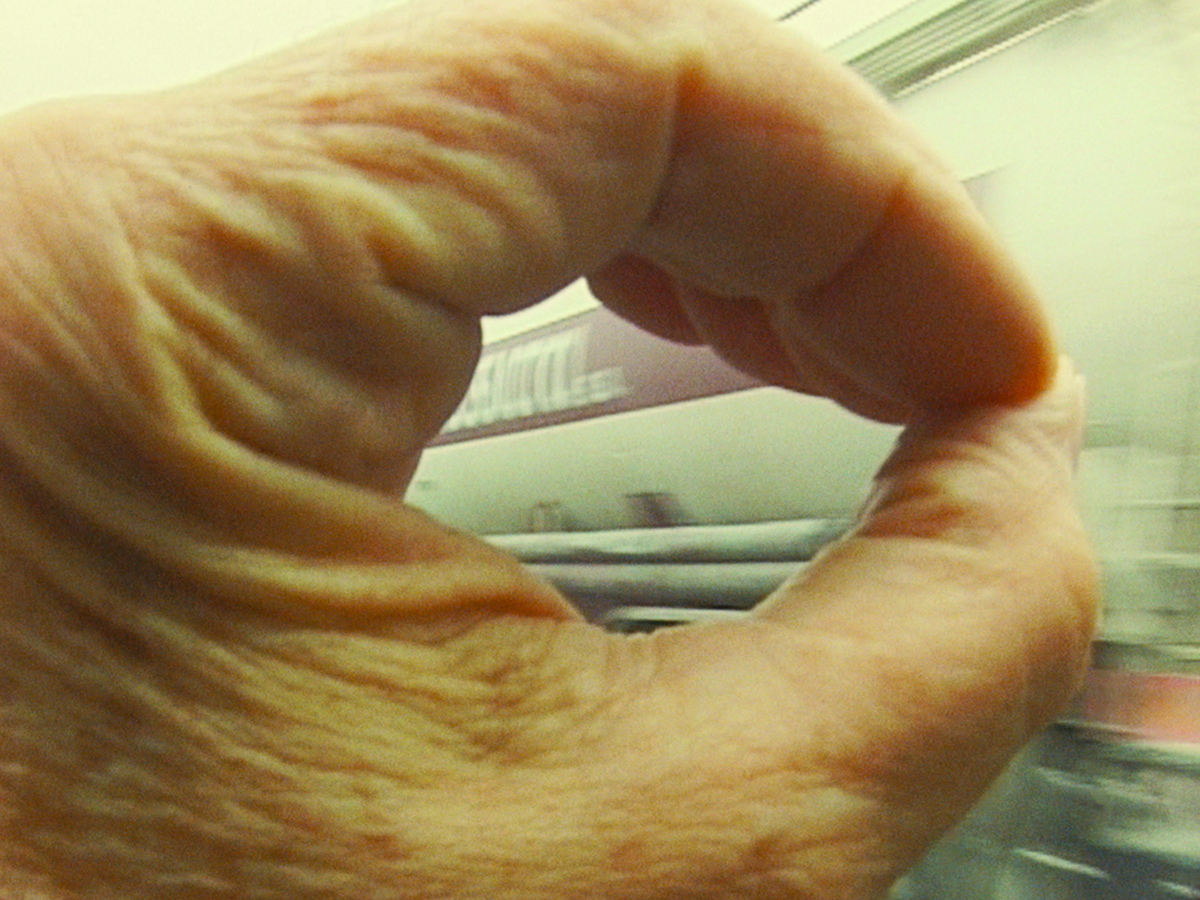

What began as an attempt to document the everyday comes to also document the interaction of two creative souls briefly crossing paths on this planet. We learn about their shared preoccupation with human rights, the power of images, representation, ephemerality, mortality, memory, and how and what one sees. A main focus becomes Varda’s vulnerability (her declining eyesight and impending mortality), which gives the film its gravitas and form.

Near the end, JR posts blown-up images of Varda’s feet and eyes on the sides of a train. A local man asks: “Why put toes on a train? Is there a point?”

“The point is the power of the imagination,” Varda says. “We’ve given ourselves the freedom, JR and I, to imagine things.”

Agnès Varda’s Short Films

L’Opéra-Mouffe (1958)

Varda was pregnant when she made this film with impressions of Paris’s rue Mouffetard. Now a chic neighborhood, rue Mouffetard was then the abode of people living the “difficult lives” that would always be a subject for her. Varda said that when she made the film she was haunted by a “fundamental contradiction.” When you’re pregnant, you’re offering life—and yet “everywhere people are unhappy.”

Like the bag from which Mary Poppins pulls the furnishings of her trade, this movie contains more than it seems seventeen minutes could possibly hold. All of the major themes, images, and techniques that would come to characterize Varda’s oeuvre are here: foraging for food (basic survival), disenfranchisement, reflections, the human face, nudes, the interchangeability of photo and film, a place between decay and life, women’s experience, images carrying symbolic weight. It’s as if Varda discovered her obsessions on rue Mouffetard and spent the rest of her life combining them in various ways.

Black Panthers (1968)

For Americans, this film is an encounter with our difficult racial history from the perspective of an outsider.

Varda was living in California with Jacques Demy during protests in Oakland, California, over the arrest of the Black Panther co-founder Huey Newton for the murder of a police officer, John Frey, in 1967. She flew from Southern California to Oakland to attend the protests as a witness and filmmaker. Along with the selections from the footage she shot, Black Panthers includes interviews with Huey Newton (from prison) and Kathleen Cleaver, who held a senior position in the party.

The film grants protesters the space to speak their truth, and the narrative voice-over, which contextualizes race issues in the United States, discusses policing in Black communities. This leads to a sympathetic portrait of the Black Panther Party and its struggle against long-standing racial injustice in the United States.

If you’re not ready to invest in the boxed set, you can see many of these films on Criterion’s streaming platform: Criterion Channel.

Leave a Comment