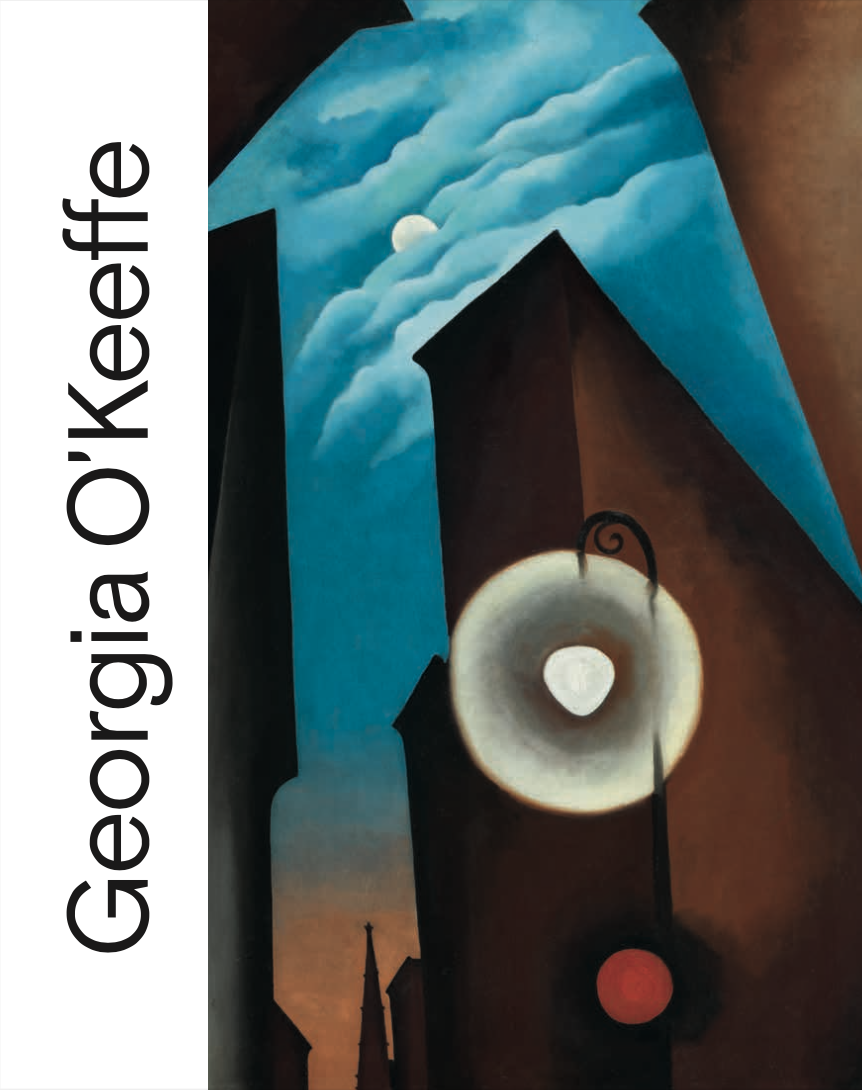

Georgia O’Keeffe (Exhibition Catalog)

Marta Ruiz del Árbol, Editor

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornmisza, 2021

With five Georgia O’Keeffe paintings in its collection, the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza (Madrid, Spain) holds more Georgia O’Keeffe works than any institution outside the United States. Using those five works as a kernel, the museum this year launched Spain’s first O’Keeffe retrospective (April 20–August 8, 2021). After completing its run in Madrid, the exhibit moved on to the Centre Pompidou in Paris (September 8–December 6, 2021), after which it will travel to the Fondation Beyeler in Basel (January 28–May 22, 2022). As in Spain, the exhibits in France and Switzerland constitute the first retrospectives of O’Keeffe’s work in either of those countries.

Curated by Marta Ruiz del Árbol, curator of modern paintings at the Thyssen-Bornemisza, the exhibition brings together 90 works spanning O’Keeffe’s career. The exhibit’s earliest works are the abstract drawings O’Keeffe executed in 1916 when working as an art teacher in Texas and the last are from the 1970s, including Sky Above Clouds / Yellow Horizon (1976–7), which O’Keeffe painted with assistance, after her vision declined due to macular degeneration. Arranged chronologically and thematically, the exhibition sheds light on the role of movement (journeys, walks, expeditions, etc.) in O’Keeffe’s creative process and foregrounds the artist’s connection to nature.

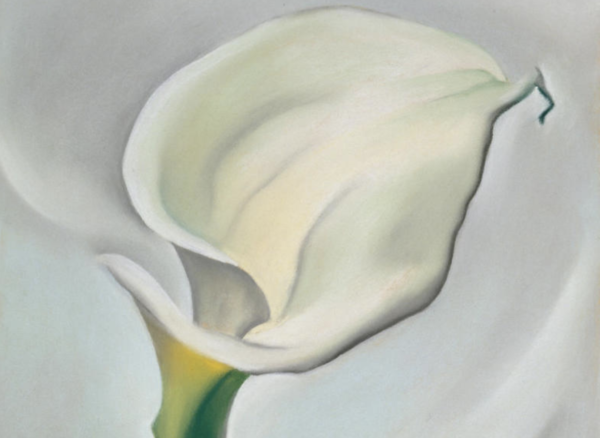

That such a major exhibition has been presented this year is nothing short of remarkable. The generous, 300-page hardbound catalogue that accompanies it offers some consolation for those unable to attend it in person. Along with 95 gorgeous plates of O’Keeffe’s work, the catalog includes six essays. It affords a fascinating perspective on O’Keeffe, one that widens the lens on a quintessentially American artist and draws attention to the far reaches she traveled in mind, spirit, body, and art.

O’Keeffe the “Flâneuse”

The catalog’s opening essay is by Árbol, who traces the vital lifelong importance of movement in the development of O’Keeffe’s oeuvre: “O’Keeffe walked to be able to draw and subsequently paint. Before picking up the charcoal, long before grasping the brush and bringing it to the canvas, the painter went for walks, and this act should be considered the first essential step in her meticulous creative process.”

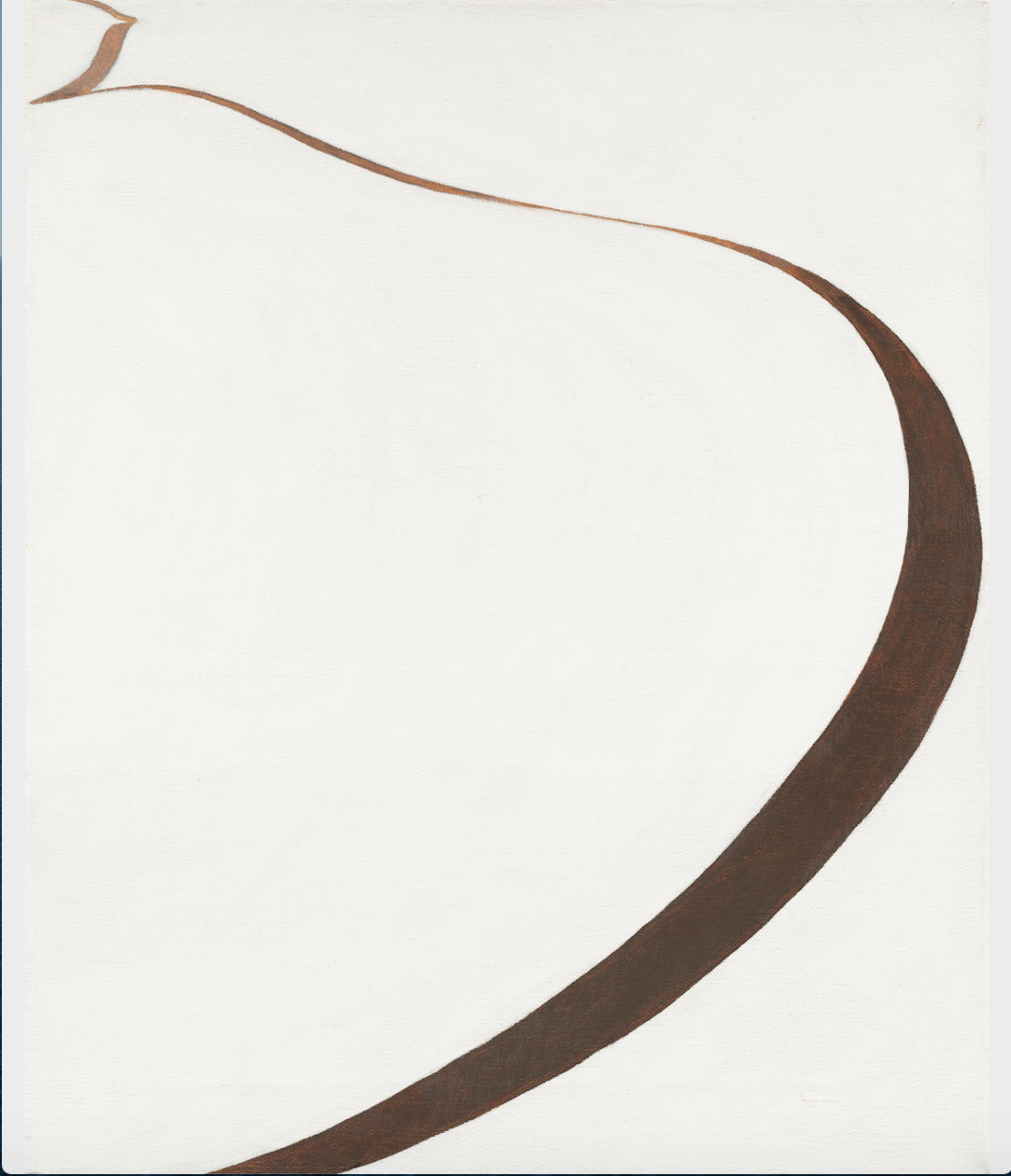

Árbol discusses how—somewhat astonishingly—O’Keeffe traveled to Europe for the first time in 1953 (when she was sixty-six years old). Though before then she’d rarely left the Americas, afterwards, she spent the next two decades journeying around the world. Árbol feels that, while Europe did not leave much of a mark on O’Keeffe’s work, the journeys themselves, the forays, the movement, the change of perspective, did. She sees that specifically in how the views from plane windows that so astonished and delighted O’Keeffe influenced the perspectival shift in late paintings such as Winter Road I (1963), which captures the serpentine wanderings of a road as seen from above.

Árbol finds in O’Keeffe’s biography a spirit of wanderlust that goes back to her childhood and played a crucial role in her creative process throughout her life. An avid walker, O’Keeffe was always exploring her close environs on foot. During her walks, she lost herself in nature, her primary subject (except in the case of her night walks in Manhattan, when the city itself became her subject). She drew and gathered materials that she would paint later in her studio.

When she began to spend time in New Mexico (1929), she continued to explore the terrain on foot but also learned to drive and subsequently converted a car into a mobile studio. This allowed her to visit and paint “more inaccessible places.”

Discovering the Great American Subject

Didier Ottinger, assistant director of the Centre Pompidou, locates Georgia O’Keeffe’s aesthetic alignment and influences within competing artistic outlooks in Europe and the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century, at a time that American artists were deeply influenced by European avant-garde movements in the wake of the 1913 Armory Show.

A wide-ranging essay, Ottinger’s scholarly approach to O’Keeffe pivots on the relationship between her and her partner, Alfred Stieglitz, who was deeply involved in the era’s conversations about art and contributed to O’Keeffe’s art education by introducing her to a number of influential ideas and writings. Ottinger sees O’Keeffe as following in a lineage emphasizing Matisse’s color rather than Picasso’s form. The Matisse lineage encompasses Kandinsky’s spiritual view of art, decorative art, the work of Arthur Dove and D.H. Lawrence, and, as practiced by O’Keeffe, an expressive abstraction and “feminine alternative” to the “machines of futurism and many European avant-garde trends.”

Ottinger suggests that after journeying through the day’s presiding ideas and having her work sexualized by critics, O’Keeffe moved to New Mexico to “forget about the barrage of artistic theories” and discover her own “great American subject.”

Influenced by Photography

In an analysis of O’Keefe’s paintings of New York, Ariel Plotek, curator of fine art at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, poses the notion that O’Keeffe’s approach to painting borrows from photography, an art with which O’Keeffe became intimately familiar through her association with Stieglitz.

One of the things that a camera captures is “halation,” the spreading of light beyond its proper boundaries to form a fog around the edges of a bright image in a photograph or on a television screen. It’s an effect Plotek sees in O’Keeffe’s paintings from the 1920s. She finds other photographic influences in O’Keeffe’s blown-up details in her flower paintings. Whereas in unmanipulated photographs, however, such effects may appear “objective,” in O’Keeffe’s paintings, they emphasized the painter’s point-of-view, craft, and subjectivity.

“A Heroine for D. H. Lawrence”

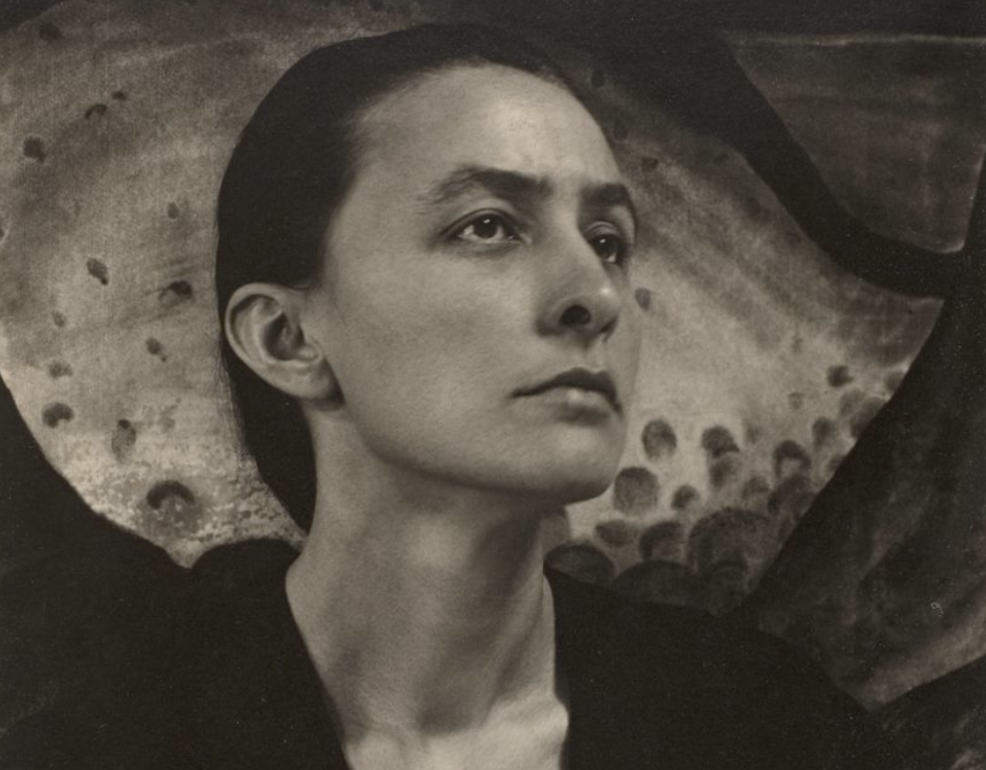

Georgia O’Keeffe and D. H. Lawrence both discovered their spiritual homes in New Mexico. Yet though they were peers and trod much of the same ground (literally), they never crossed paths. French art writer, critic, and curator Catherine Millet writes about what, beyond their love of New Mexico, O’Keeffe and Lawrence share. She sees in O’Keeffe the archetype of the heroine from a Lawrence novel who gets up and leaves. In O’Keeffe’s case, it was Stieglitz she left when she fled to New Mexico for the first time in 1929. He had begun an affair with Dorothy Norman, and by escaping from him, if only temporarily, Millet suggests that she was both fleeing from a situation that caused her pain and “shedding the image he had shaped of her,” that of a “child woman.”

Millet feels that O’Keeffe and Lawrence were both nostalgic for “sweeping landscapes where the light disintegrates human identity.” She imagines that if they had met, they might have discussed “wide-open spaces,” but maybe little else.

Like several of the other essays in the catalog, Stieglitz looms large in this essay as a formative influence in O’Keeffe’s career—and an emotional crucible that brought O’Keeffe “closest to the sources of life” that she revealed in her work.

O’Keeffe’s materials and techniques

For those interested in the technical side of painting, two essays delve into the materials and techniques behind O’Keeffe’s work. The first looks at her preferred pigments and canvases at various points in her painting career. The other sheds light on her painting process—from the supports she used as the base of her paintings to the implementation of paints, varnishes, and frames—by looking closely at the five paintings in the Thyssen-Bornemisza’s collection.

The closing biography by Anna Hiddeston-Galloni, presents the details of O’Keeffe’s life in a detailed chronology that is richly illustrated with photos of O’Keeffe and her milieu.

O’Keeffe has been written about more than perhaps any other American woman artist. This catalog, which is sure to hold its place as a crucial contribution to our understanding of her life and work, is not only a gorgeous presentation of her art. It’s also testament to the fact that there is still much to discover and appreciate about this artist and that, in light of current environmental concerns, her vision of the world—and nature—gives us much to ponder.

In addition to the English-language version of the catalog, a Spanish-language version is available through the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza and a French language one through the Centre Pompidou.

Further Reading