Looking vs. Seeing

September 14, 2021

From our archives: we first published this blog post in August 2014, early in our work at the Vision & Art Project, but we’re reposting it now because it remains a vital discussion of some of the fundamental principles at the heart of our work.

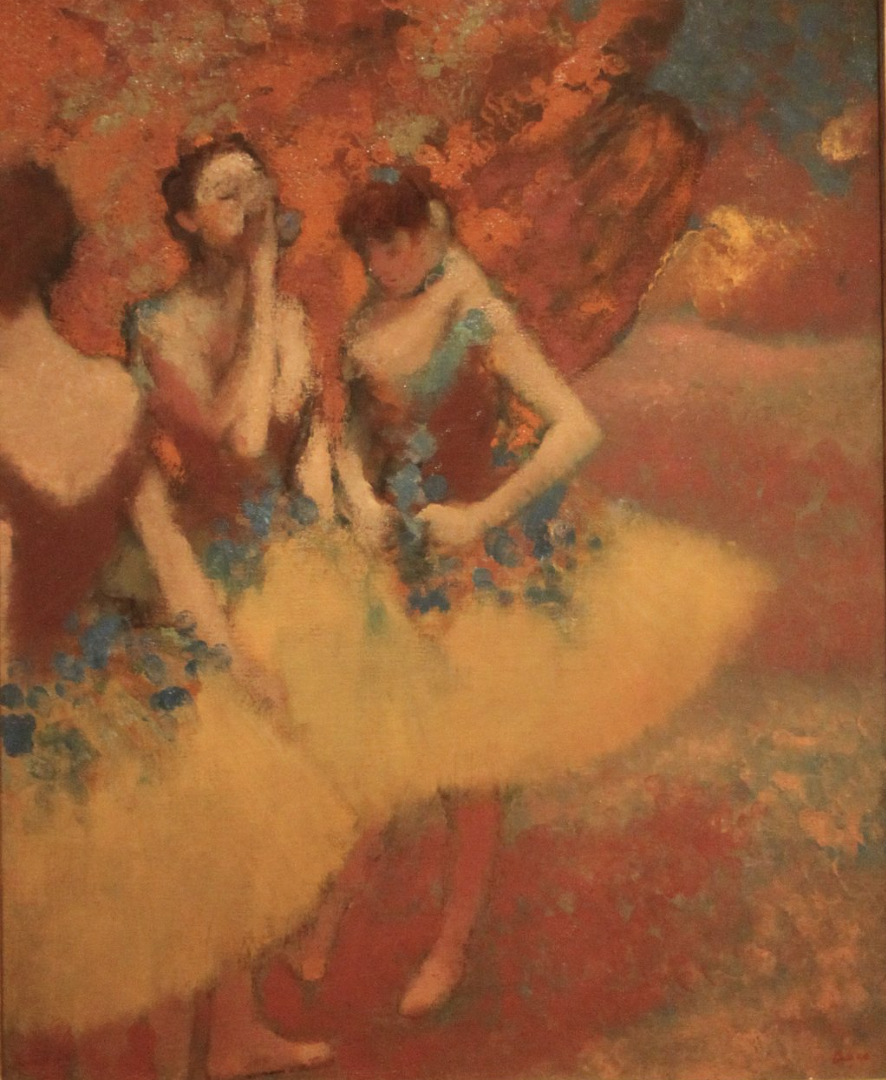

It is perhaps not well known that Edgar Degas painted some of his most influential and successful works of art while nearly blind from macular degeneration. As early as in his mid-40s, he wrote to his family and friends about the fear and suffering he faced as a painter with failing vision—this well before the height of his career.

How can an artist such as Degas, deeply trained in and devoted to working with his faculties of visual perception, though working with severely compromised sight, play such an instrumental role in shaping the history of visual arts?

Macular degeneration is unique in the spectrum of visual pathologies in that it obstructs and obscures vision in a myriad of ways, but rarely precludes the retention of at least some degree of what we might consider normal vision.

Where macular degeneration leaves vision fragmented, scattered, warped, and uniquely altered, cataracts on the other hand imparts an undifferentiated and yellowed spectrum to all that is seen. Macular degeneration is unique in this way, that it renders reality to be reassembled in the mind’s eye. As such, it offers us an opportunity to explore the visual experience in ways equally unique, in ways we likely otherwise would not. Artists who continue to paint with macular degeneration are not only sharing in the experience of others who struggle with partial vision loss. By virtue of the paintings and sculpture they create, they are also sharing their experience with the rest of us as well. Their works of art embody the narrative inherent to adaptation in the face of loss, the commingling of what had been with what must be.

At the surface, the ability to see can seem like a self-evident and universal human experience. We point our eyes and behold. What does it mean for a work of art to be “well seen,” though, especially that which is created by a painter who is nearly blind? Great artists are always teaching us that the ability to see can be chimerical, more complicated than we might sometimes assume. We all know that it is easy to look at something or someone and not to see them. Or to look at something and see only what we know to look for, or only what we want to see, or only what we remember. In other words, to look is not necessarily the same as to see. Nor is vision limited to the image that hits the retina of the eye. Vision is also desire and memory and the mysterious workings of our inner and completely personal reality. Nowhere is this more evident than in paintings and drawings created outside the spectrum of “normal” vision.

Great artists who continue to paint with macular degeneration, who see the world differently than they once did, who adopt new working practices, who take on new subjects, who offer up new visions of reality for us to share and contemplate, remind us of the beauties and mysteries of vision. In sharing their work, they invite us to take in the world around us anew. A cup, or sunlight on the kitchen floor becomes disembodied color and shape, or it becomes a visual experience altogether outside our ability to understand or describe with language. What was once the familiar turn of a handle on a tea cup becomes a strange and unique form that carries with it an emotional charge, a sheen, a curvature, a texture unlike anything else, or perhaps precisely like something else. What we thought we knew gives way and makes room for something altogether new.

Visual artists who press on in the making of their work through partial or complete vision loss are stewards of an entirely different kind of vision that is no less “well seen”—a complicated place where memory, insight, perseverance, creative problem solving, openness, force of will and surrender prevail and collaborate to shed light on new and often inspiring things.

Comments

MORE Brian!!! Say more!

Fascinating to “see” how you are “looking” at the issue of vision and art.Thank you!

This Vision and Art Project is, in a word, ILLUMINATING! This is a terrific article, shedding light on a subject many of us know little about. I’ll continue to visit the site to learn more.

Very interesting article…. I’m still musing on “to look is not necessarily the same as it is to see.” ……. so true in the

experiencing of art in general, and so often, life in general…..

Thanks very much for presenting this perspective on painting/drawing/making art. So interesting that many great artists have been challenged by vision impairment. For the first time I understand that great art develops with attention, trust, patience, and curiosity, and these are more important than the artists physical gifts.

Thank you so much for this great reading about vision and art. This is a great reminder that one has to be honest and true to himself, guided by his/her inner vision and intuition. Van Gogh would be another example – because of some drugs he experienced haziness in his vision.