V&AP Benefit Exhibition Artworks on View at the Lighthouse Guild

September 05, 2024

The Vision & Art Project launched its tenth anniversary this past spring with our exhibition, What Was Once Familiar, at the National Arts Club in Gramercy Park, NYC, which featured artists with vision loss due to macular degeneration.

A selection of these works are now on view at the Lighthouse Guild (250 W 64th St, New York, NY 10023). These include paintings and prints by Lennart Anderson (1928–2015), Robert Birmelin (b. 1933), Serge Hollerbach (1923–2011), Robert Andrew Parker (1927–2023), and Erika Marie York (b. 1990).

The Lighthouse Guild is a non-profit organization serving the visually impaired. Given this context, it was crucial to make our exhibition as accessible as possible to people with low vision. To do so, we wrote descriptions for NaviLens, a phone app that the Lighthouse Guild and many other institutions uses to help people with low vision navigate their environments. While this app is perhaps best known for making spatial navigation in cities and buildings smarter and more inclusive, it can also be used to make artwork more accessible through audio described content that users can listen to on their phones—a state-of-the-art audio guide with inclusivity at its core.

Writing accessible descriptions made us love these works even more than we already did

Collaborating with the Lighthouse Guild on this initiative transformed our relationship to the artworks we wrote about. To bring these paintings to life we had to do more than simply describe what we saw when we looked at them. We also needed to identify how we felt, what we remembered, began to think about, what kinds of questions and associations came to mind. As we grappled with the challenge, the minutes we typically spend looking at artwork turned into hours. As we wrote and re-wrote, we came to appreciate the uncontainable meaning and beauty in these works—their infinite potential for significance—and how efforts to make art accessible enrich everyone involved, requiring as they do a deeper engagement with the works under consideration, the need to slow down long enough to lose yourself in something of importance, to contemplate something with your memory, your mind’s eye, and your heart.

Below are the twelve works on display, as well as what we see and love when we look at them.

These twelve works, as well as many others, are available for purchase through December 31, 2024, at our online benefit exhibition site, with proceeds to benefit The American Macular Degeneration Foundation (AMDF) and artists with vision loss who contributed work.

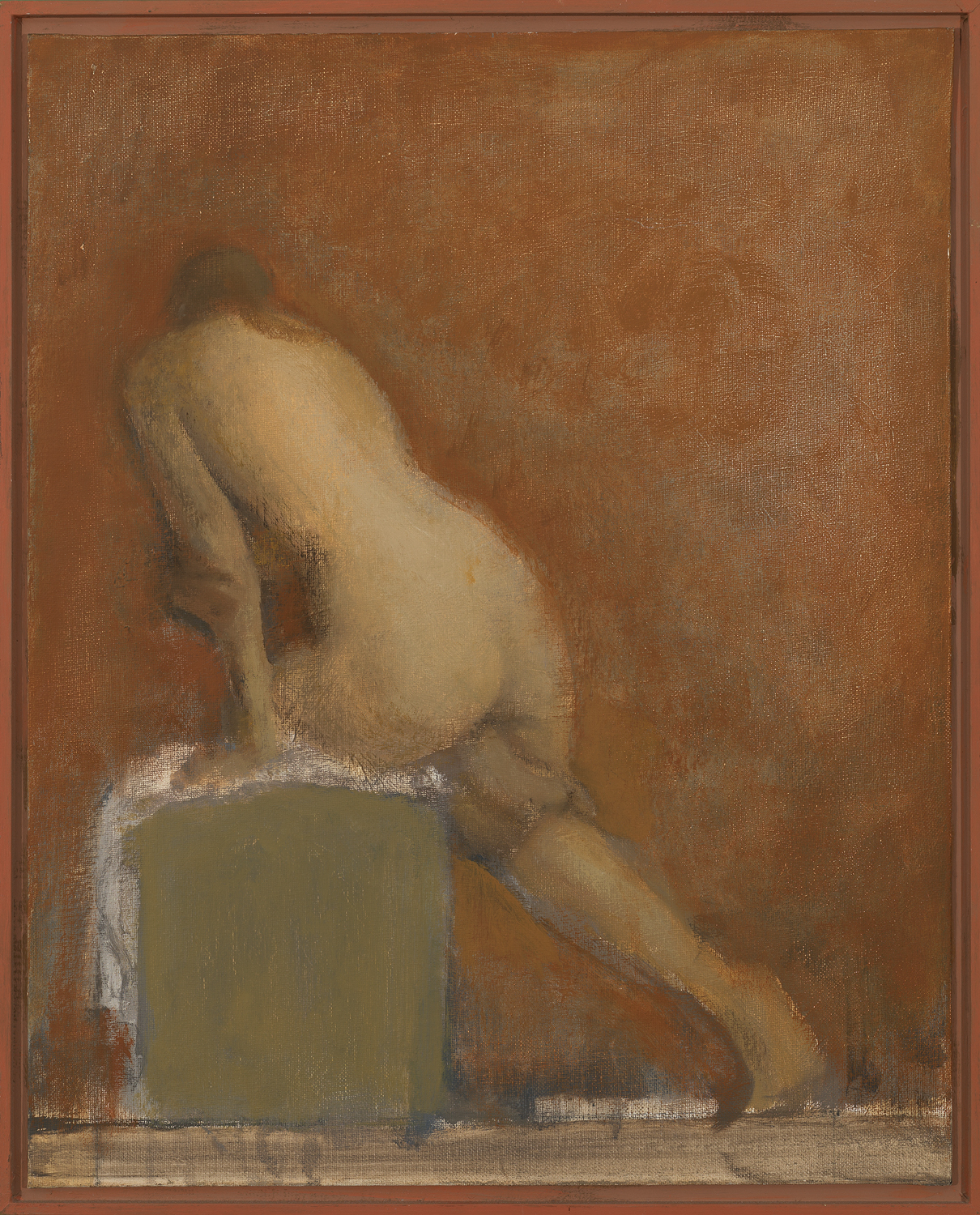

1. “Back View, Woman on a Box,” by Lennart Anderson

The scene

A nude woman is posed with her back to us. The left side of her body is perched on a box; her left buttock and thigh visible, her left arm supporting the weight of her shoulders and upper body, palm of her hand pressing against the top of the box. Her right leg stretches out behind her to the right and head is tilted down and away. Her rounded back is the lightest value in the painting and our focal point. The woman’s pose creates a powerful diagonal line from the upper left of the canvas to the lower right, bisecting the painting into distinct zones of two nearly perfect isosceles triangles. The nude fills the lower triangle, and the upper triangle is empty, save for an evocation of the atmosphere around the figure: a muted interior pulsing with light that is conjured with scumbled strokes of semi-transparent umber paint.

What we notice / why we love this painting

The painting is muted and warm, with a limited palette reminiscent of a classical academic study. But this painting is quite different from a classical study of a nude. This painting makes us feel the model’s struggle and discomfort as they hold a pose for 20 or 25 minutes before breaking. Here, the strain of the model, as telegraphed in her rigid arm and her hand, braced against the box, is palpable. The depiction of this strain, which any model knows, transforms what could have been a detached study of a nude into an empathetic depiction of an individual that makes the viewer aware of her personhood.

This painting also differs from a classical study of a nude in its handling of the atmosphere, the way in which the negative space around the model pulses with light—and significance. Lennart Anderson was known for his astute and sensitive renderings of perceptual experiences, so much so that he was at the forefront of a movement in realist art called “perceptual painting.” In Back View, Woman on a Box he paints not the idea of a nude seen from behind but the visual experience of a moment in time. A choreography of soft edges and close tones that evoke not only a person propped up on a box but a luminous visual experience of light on form where our focus is not on nudity so much as the quality of light at a particular moment of being.

Through its abstractions and muted tones, we encounter not a woman alone posing for an artist with her back turned to us, but a singular instance of struggle seen as though for the first time and yet familiar, ineffable, and timeless.

To inquire about purchasing this painting, please contact A’Dora Phillips at aphillips.visionandartproject@gmail.com, or visit our online exhibition site.

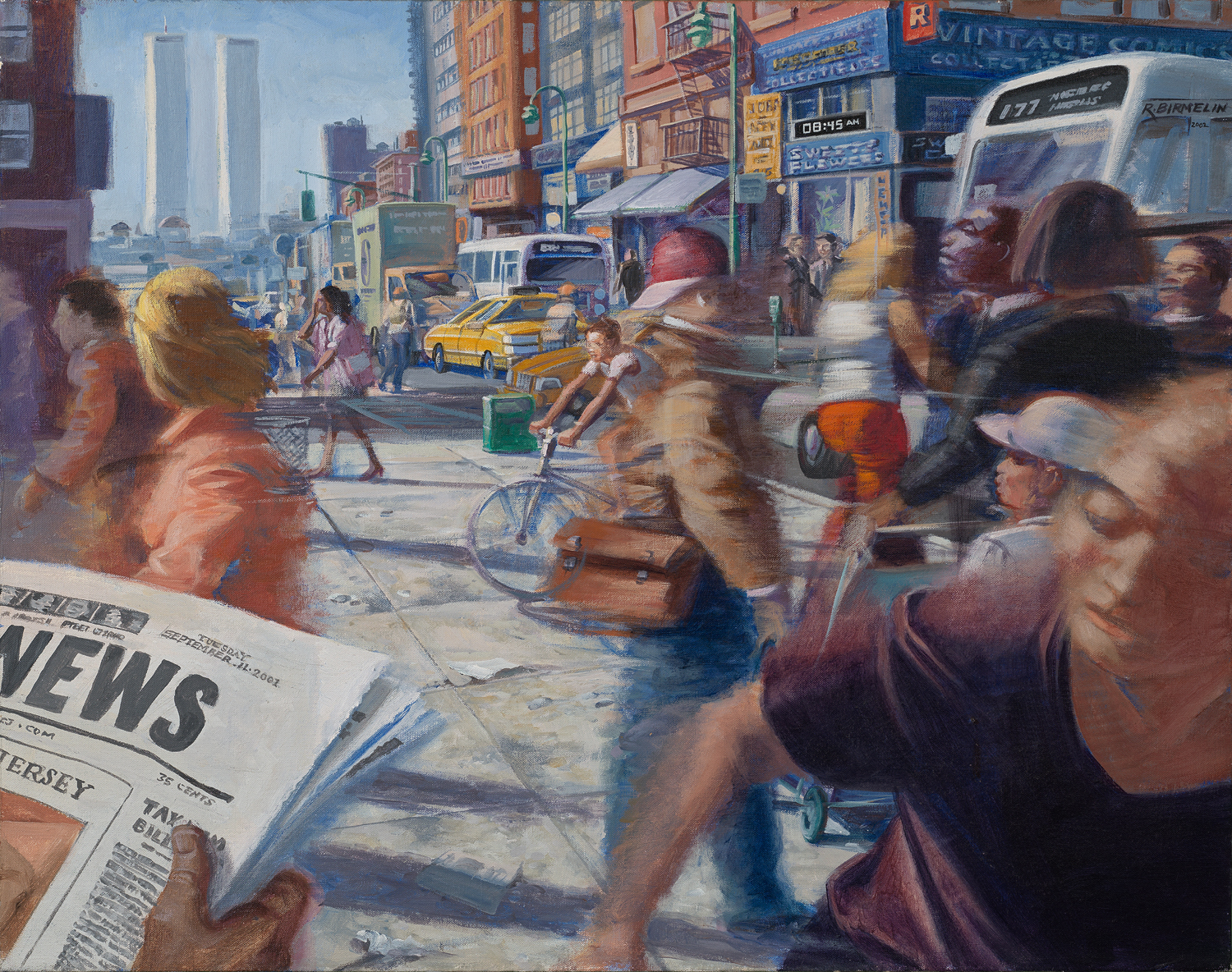

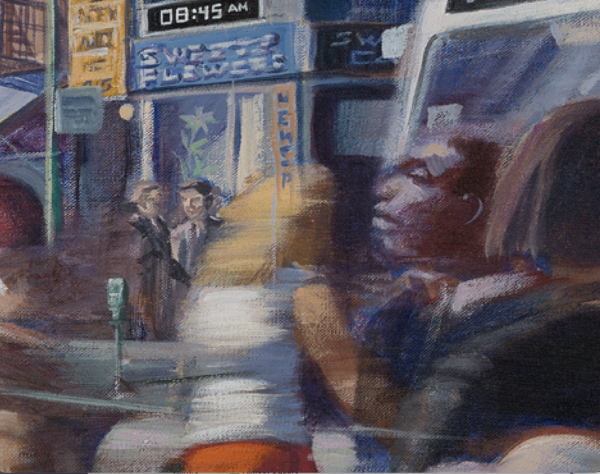

2. “The Morning of September 11, 2001, 8:45 AM,” by Robert Birmelin

The scene

A street in New York, busy with people going about their business, with, in the far distance, the twin towers against a hazy blue sky. In just a few minutes, the first tower will be struck by a hijacked plane; we know from the painting’s title and the clock above one of the storefronts.

Morning light streams across the busyness, casting long shadows on the sunny pavement. At first glance, this scene conveys the chaotic amplitude of New York that moves through and past our perceptual field. It is almost as if a camera has captured everything within its eye. We perceive the street as a moment in time, figures caught mid-stride, blurred with movement. The painting is vibrant with color: bright clothes, yellow cabs, a green receptacle, warmly lit facades tinged with blue or made of red brick. Despite the bustle and brightness, however, the painting does not exactly convey an impression of pleasantness. Aside from the unease imparted by the title, this urban scene conveys the human and sensory abundance of New York City, which can often feel overly dynamic, indifferent to your presence, and overwhelming with its numerous focal points.

In the foreground, a woman on the right walks toward the viewer; the cropping of part of her body and head by the painting’s edge implies that she is about to disappear from view. Her eyes shut, mouth in a somber line, she glances back, as if, Cassandra-like, she senses what is about to happen. In the opposing corner of the painting, a cropped hand and newspaper show the word “News” in print too large and bold to fit any other part of the paper’s name than the headline: the news is about to obliterate all else.

As is nearly always so on a street in New York in the morning, people move resolutely, heedless of one another, growing smaller as they recede into the background. In the middle ground, several figures move east, distinctly individual yet forming a conglomerate movement: a woman with an orange jacket, a woman with an oversized bag pushing a stroller, a boy on a bicycle who pedals through the intersection. Other figures trudge west: a man with a leather satchel, a woman in tight orange pants. Like the cropped figure in the foreground, do a few of these figures sense the impending cataclysmic event? It seems they might. The blonde hair of the woman in the jacket swings back as she turns her head toward the towers; the woman with the stroller has her hand to her mouth; and a Black man in a suit looks up toward the sky.

What we notice / why we love this painting

While this painting presents a single cohesive scene, it has dozens of finely rendered details embedded within it: the price on the newspaper (75 cents), the buckles on the leather satchel, the lettering on storefronts, the numbers on buses. Sometimes such a plethora of details in paintings can take away from the integrity of the whole or come across as self-indulgent on the part of an artist. But in this painting, these details seem to be offered as an act of generosity. Given to us as something we can continue to discover and contemplate. Crumbs in the unfolding narrative of that morning.

In an interview with A’Dora Phillips at the Vision & Art Project, Robert Birmelin talked about making this commemorative painting:

“My studio was on 14th Street and 7th Avenue in 2001, which was the far edge of what closed down that day. I wasn’t in New York on 9/11. I had gotten up to get the bus to go into the city, and Blair, my wife, walked up to tell me what had happened. My son was at one of the hospitals uptown, and he, with several other physicians, went down to what was then St. Luke’s (which was in the Village; it now no longer exists) to care for wounded people, and, as he said, as it worked out, few people came. This painting was done for a commemorative exhibition that occurred the following year.

My thought was to depict an ordinary day just before this cataclysmic event occurred. The contrast between what was to happen and people just going about their business. In the distance, you see the towers, and I’ve worked the time in on the façade of a building—just a minute or two before. Like a lot of people, 9/11 moved me deeply. I went to the scene a few days afterwards and made a drawing or two there.”

This painting was done before the artist was diagnosed with macular degeneration in 2016. It belongs to an important part of his multifaceted oeuvre, his urban street scenes, which he explored over many decades beginning in the 1980s. Since developing macular degeneration, he has found it hard to paint. Instead, he is drawing with a black pen, whose marks, in contrast to the white paper, he can clearly see. He sometimes still uses color, though in a limited way, adding gouache and watercolor to more linear underpinning, thus doings things, as he says, that “hang between drawing and painting.”

To inquire about purchasing this painting, please contact A’Dora Phillips at aphillips.visionandartproject@gmail.com, or visit our online exhibition site.

3. “The Lost White Dog, 14th St., NYC,” by Robert Birmelin

The scene

In a painting saturated with color, people hurry up the steps of a subway station onto a street where a small white dog trots along a sidewalk. In the foreground, a man holding a newspaper, part of his body cropped by the edges of the painting, looks out at the viewer.

Although the dog’s gait seems confident, the truth of its plight is in the leash it drags, still attached to its collar, as well as its drawn-back ears and small red tongue, panting more with anxiety, one feels, than exhaustion. If anyone in the painting is aware of the dog—or one another, for that matter—it isn’t evident. While the dog’s lostness may be the main focal point for viewers, guided as we are by the painting’s title, that doesn’t seem to be so for the people in the painting. Though it’s hard to judge, since most of them have their backs to viewers or their faces blocked. Undoubtedly, though, they rush along. Seemingly unaware of the dog. Or indifferent to it.

What we notice / why we love this painting

Robert Birmelin has made very large paintings of street scenes, and by comparison, this one is small, not much bigger than two legal sized sheets of paper taped together. Yet despite its modest size, this intimate painting calls for a similar intensity of attention. As Birmelin’s larger works do, this painting draws the viewer into the scene at hand. As one critic has described, it’s as if the picture plane is a thin membrane between the private world of the individual and the world inside. It is easy to project oneself into that world, easy to imagine the people inside it stepping out to where you are.

It’s typical in a Birmelin street scene for a figure to press up against the picture frame, as if barely contained there. In the case of this picture, it’s a Black man, on the other side of the membrane, gazing somberly toward the viewer. Inexplicably, though, he has his eyes closed. Still, you sense him looking at you, not so much, it seems, as to ask what you would do were you to come out of the subway and notice a poor, lost dog, but rather to empathize with the pain you feel about the dog’s plight—and about the plight of all the other relatively defenseless souls, trying to survive this vast, indifferent world where strangers do not intercede, do not make contact.

To inquire about purchasing this painting, please contact A’Dora Phillips at aphillips.visionandartproject@gmail.com, or visit our online exhibition site.

4. “Camden, NJ” by Robert Andrew Parker

The scene

A miracle of loose brushstrokes and linework summon Camden’s skyline on a day with hazy blue skies. Geometric neutral-colored buildings smudge one into another and bristle with glimmers of sunlight. Lines drawn in dark paint outline some of the buildings and suggest roads or electrical wires or antennae—or some other city infrastructure that ensures connectivity. Seeming to evoke the painter’s mind as he traveled across the canvas, these lines skate calligraphically, delightedly, across the painting’s surface, thickening and puddling near the base of buildings and on the right side of the picture plane, where a few tiny dark silhouettes of people populate a gap between buildings. There are wispy streaks of clouds in the sky, as well as a few detached white cottony cumulus balls, which makes the viewer aware of an ever-changing sky, of light, of wind.

What we notice / why we love this painting

After seeing Parker’s artwork in the 1950s at the Museum of Modern Art, the poet Marianne Moore wrote an essay lauding him as “one of the most accurate and at the same time most unliteral of painters.” She saw him as combining “the mystical and actual, working both in an abstract and a realistic way.” Parker did this painting more than six decades after Moore wrote about him and more than a decade after he was diagnosed with macular degeneration, yet Moore’s description remains apt. In its accuracy of observation and inventiveness of design, this painting is remarkably like the work he did early in his career, save perhaps a less definite line and hazier horizon, both of which lend something ineffably pleasing to its overall effect.

To inquire about purchasing this painting, please contact A’Dora Phillips at aphillips.visionandartproject@gmail.com, or visit out online benefit exhibition site.

5. “Annapurna, Nepal” by Robert Andrew Parker

The scene

A painting of a white-capped mountain. Above it, a bluish-purple sky is etched with the thin orange streaks of a setting sun and wispy grey and white clouds. Most of the mountain is dark, but the brown paint used to depict it has been laid over a warm orange-red underpainting. With the end of a paintbrush or some other blunt tool, the painter drew into the brown paint while it was still wet to expose glimmers of this orange beneath. A set of three parallel lines drawn in this way horizontally from the left-hand side of the canvas to the right carves out what appears to be a road or trail, glinting in the evening sun, while a more random scattering of vertical marks gesture towards trees, vegetation, and the upward thrust of rock.

What we notice / why we love this painting

This painting combines picture with calligraphy and comes from a time in the artist’s life when he traveled widely around the world, often publishing the writings he did onsite at far-flung places in magazines such as Time, The New Yorker, and Sports Illustrated.

To inquire about purchasing this painting, please contact A’Dora Phillips at aphillips.visionandartproject@gmail.com, or visit out online benefit exhibition site.

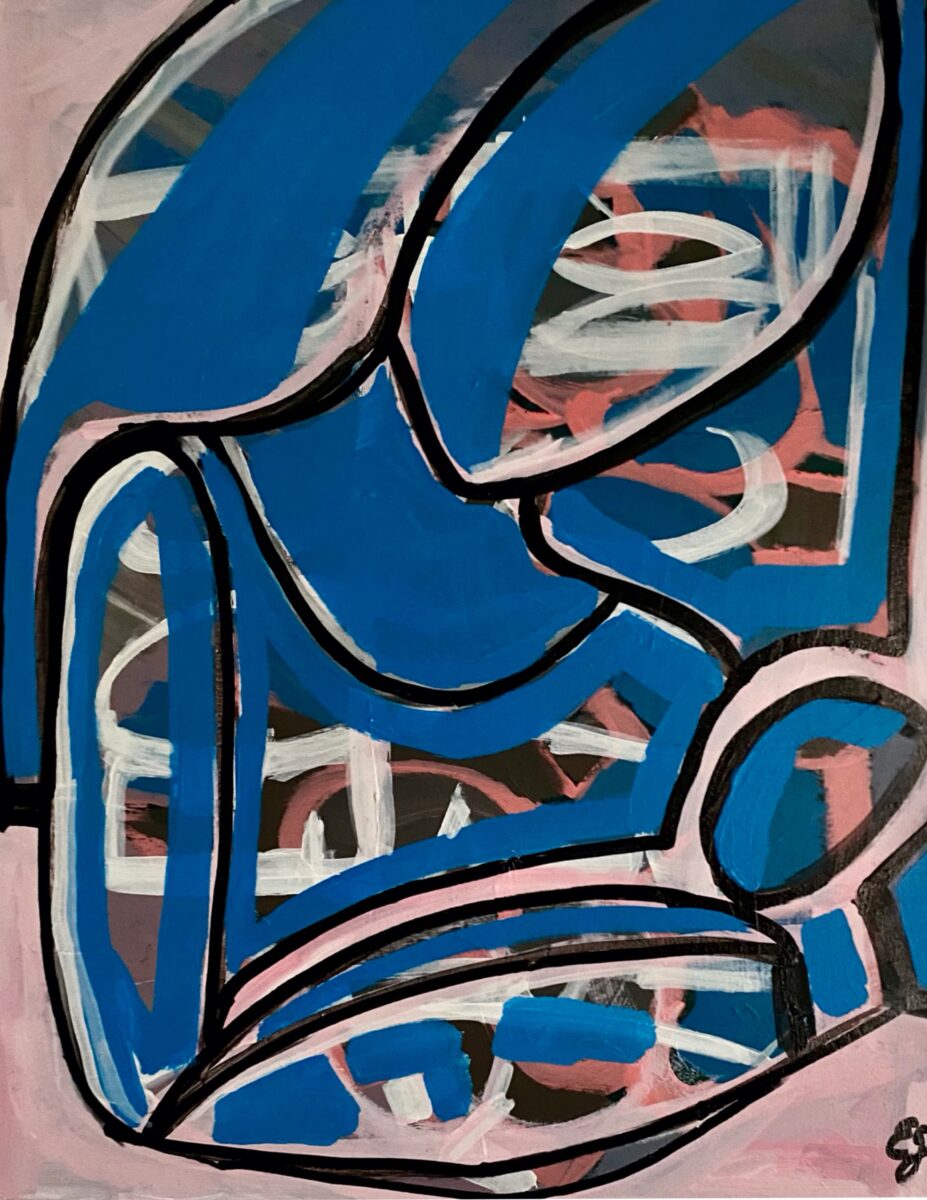

6. “All for You” by Erika Marie York

The scene

This is a painting of a mother and child. The woman’s upper body shows, holding a baby in the crook of her arm. Her head—faceless—is tilted toward the child; the baby’s head—also faceless—is nestled against her shoulder and gazing up at her. As in a work of graffiti, the shapes that make up the figures are boldly geometric and outlined in black paint—the mother’s upper and lower arms are cylinders, her torso is a square, her and her child’s heads are ovals.

These shapes are filled in with flat blue paint of an unvarying hue, as if poured onto the canvas unmixed from a bottle. Colorful jigsaw-shaped passages sporting an abstract design interrupt the seamlessness of the blue paint. These jigsaw pieces are dominated by a pinkish-orange hue and look a bit as if they’ve been cut out from a cuneiform alphabet of the painter’s own making and pasted onto the painting.

What we notice / why we love this painting

As the writer Alice Mattison has noted in her introduction to the catalog for What Was Once Familiar, the artist concentrates on feeling here, not the details of appearance. As Mattison says:

“It’s a familiar subject and our culture tells us what such a woman feels—some kind of private joy. But in this painting, the peaceful blue of the woman’s body as a whole is almost violently interrupted here and there: we move into intensely colorful, apparently three-dimensional areas of wild feeling, in which brown is covered by streaks of pinkish orange, and that color sometimes by white.… [W]hat she feels is a complicated, roiling mix. Excited white strokes are most numerous on her face. The baby’s belly also has the turbulence of those white lines, but the quietest spot in the painting is the baby’s head—some of it the bright color, some darker. The child, unquestioning, receives and calmly returns (we don’t see the face, but the baby’s pinkish-orange thoughts point upward) the mother’s intense gaze.”

It is notable that the figures in this work do not have faces. The artist developed Stargardt disease, a juvenile form of macular degeneration, in elementary school. In an interview with A’Dora Phillips, York says that if she didn’t have Stargardt, she can’t imagine what her paintings would look like. Their signature qualities—bold lines, bright colors, figures often lacking facial features or wearing glasses—are largely shaped by her eye condition. These very same qualities give her figural-based paintings a powerful graphic impact.

To inquire about purchasing this painting, please contact A’Dora Phillips at aphillips.visionandartproject@gmail.com, or visit our online benefit exhibition site.

7. “City at Night” by Serge Hollerbach

The scene

A moody nighttime cityscape is composed of abstract shapes of primary colors grounded in a field of black. In the background, the night sky is a strip of vertical, dark, cerulean blue pinched between the looming silhouettes of what appear to be two imposing buildings rendered in pure black. A sidewalk and street fill the foreground, with uniformly dark tall buildings in the background, as if cut out of one continuous sheet of black construction paper.

Also in the foreground, four figures painted with loose, neutral brushstrokes trudge along the sidewalk, three turned away from us heading to the left, and one foraging forward to the right with head down and a baseball cap pulled low over their face. There is a sense that these people are on their way home after a long day at work, lost in thought, each alone in their own world. A handful of additional figures walk on the opposite side of the street, farther away, smaller, ghostlier, more indistinct. On the left side of the canvas, the yellow headlights of a car glow like a cat’s eyes in the dark of an alley. Square, shiny building facades shine with the illuminating artificial light of the city in hues of pink, white, and red.

What we notice / why we love this painting

Though not dated, we know this is a late painting because of the quality of the shapes and color that consistently distinguish the work Hollerbach made after experiencing vision loss due to macular degeneration. (The loose, abstract rendering is typical of Hollerbach’s late work.)

Before he lost his vision, Hollerbach’s figures were often replete with precisely observed details such as carefully drawn facial features. But Hollerbach believed body language and gesture could tell a story about a person’s essence better than carefully rendered details. After he lost his vision, he turned his talents to distilling the essence of larger shapes that evoked the gestural language of the human body. Posture conveys a great deal of information about his subjects, including whether they are young or old, their gender, and their body type. From these shapes we discern what emotional reserves his people might have at the end of a long day: whether they are elated, or lost in thought, or spiritually depleted and alone.

The black paint that suffuses this painting is essential to its essence, not so much because it speaks in a literal way toward how dark a city can be at night—which of course is not black at all—but because it evokes a larger, non-representational truth about how it feels to be heading home on a short winter evening in the city. It was this emotional truth—how things feel—that Hollerbach was interested in evoking in his late, post-macular paintings.

To inquire about purchasing this painting, please contact A’Dora Phillips at aphillips.visionandartproject@gmail.com, or visit our benefit exhibition website.

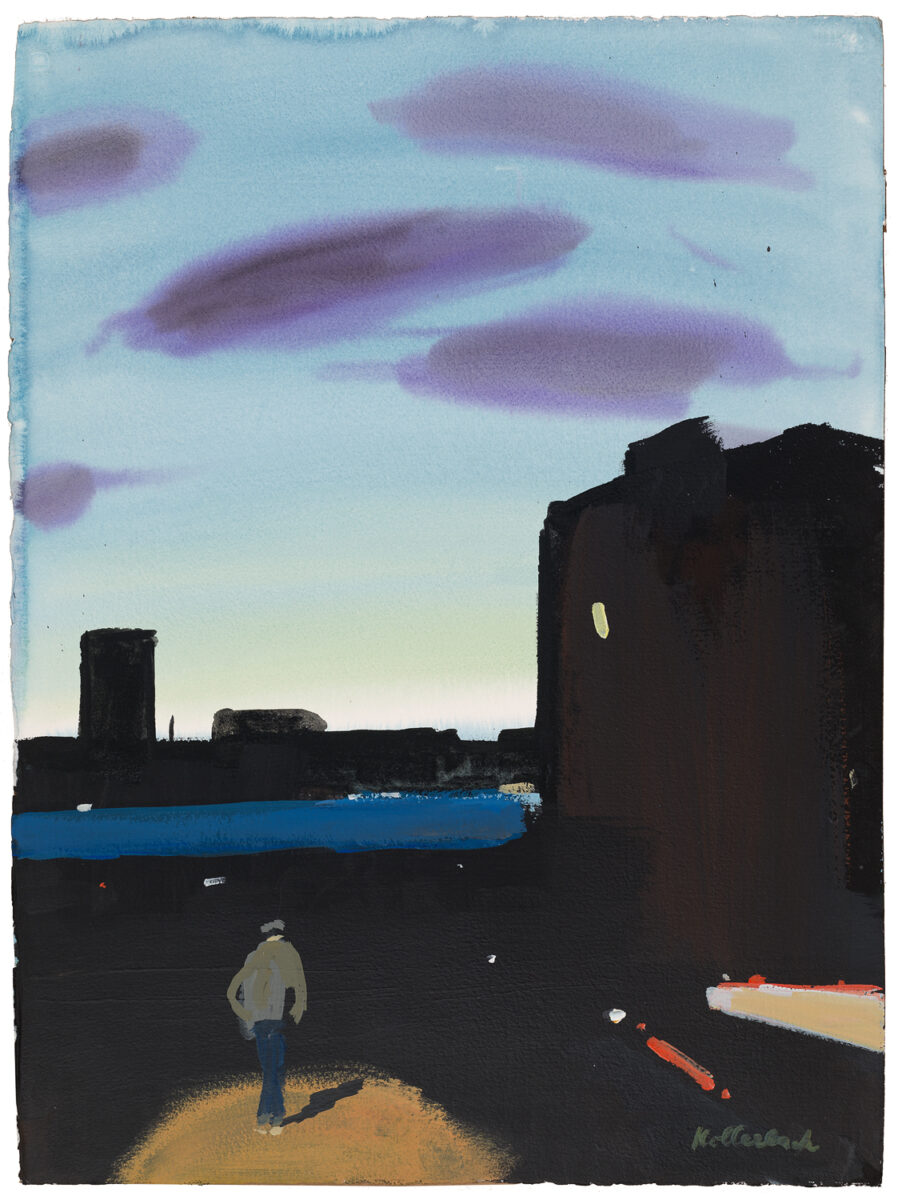

8. “Pale Sky” by Serge Hollerbach

The scene

A lone figure, his back to the viewer, stands in a half circle of theatrical ochre light in front of a dark cityscape. The city is constructed of black rectangles seemingly fused one to the other to create a monolithic, distinctly urban skyline. This monolith dominates the lower half of the canvas, its blackness broken by a few bright spots of lit windows and a line of cobalt blue paint drawn horizontally from the right side of the painting toward the left, before being interrupted by the tallest building, which hovers over the right side of the picture. While the blue strip breaks up the potential monotony of the dark buildings, it also represents the Hudson River and thus places the scene as looking west toward New Jersey from the Upper West Side of Manhattan as the sun is setting.

In the painting, the sky, which fills more than half of the canvas, still has light in it, a strip of ivory light like a halo above the dark silhouettes of buildings. The sky gets darker as it moves upwards, the ivory halo gradually transitioning to a pale, translucent greeny hue and then a wash of blue watercolor that becomes less transparent higher in the sky. Five oval purple shapes of various sizes hover in the sky. Because of their location, they read as clouds, though they are more like purple blobs than naturalistic depictions of clouds.

What we notice / why we love this painting

On the surface, this painting depicts a rather straightforward urban motif—the city at night. But despite its familiar scene, it is far from “realistic.” Decisions that Hollerbach made give the work an enigmatic and highly emotional presence. The striking blackness of the urban silhouette evokes the emotional weight of the city, dark and vast. A high tonal contrast between the dark and light shapes makes this scene unique, most notably where the dark silhouette of buildings meets the ivory ombre glow of the sky, creating a powerful sense of drama. The one lone figure who walks away from us with their back turned is notably small and alone, diminished by the scale of city and sky. In a film made by the Vision & Art Project in 2021, Serge Hollerbach talks about the solitariness of his figures and how he uses them to explore a condition of aloneness that is at the core of human life. This painting conveys that with particular intensity.

To inquire about purchasing this painting, please contact A’Dora Phillips at aphillips.visionandartproject@gmail.com, or visit our benefit exhibition website.

9. “Hanging Out” by Serge Hollerbach

The scene

Three figures stand together in a field of simple geometric color shapes. The figures are rendered somewhat abstractly, in a style reminiscent of cubism, with angled lines, simplified features, and exaggerated gestures. Each is carved out of off-white paint and looks as if it has been collaged on to the canvas against a flat geometrical background of orange, mustard yellow, and pale pink shapes.

The two most prominent figures appear to be women, one of whom dominates the right side of the canvas and the other the left. The one on the right is standing in a contrapposto pose, her left knee bent, right hip tilted up. She faces the viewer, though her face, one side smudged with shadow, has only the merest suggestion of features. The figure on the left is in profile. She leans against a vertical blue shape that runs down the left side of the canvas, her right leg bent, foot braced as if against a wall. It’s not clear if the third figure is meant to be male or female, but everything except their head, neck, and a hint of torso is cropped from the painting, emphasizing the sense that the figure is leaning forward from outside the picture plane on the upper left, avidly listening or hoping to participate in some way.

The style of this painting is consistent with others Hollerbach did early in his career, before he developed macular degeneration. We thus know these abstractions of form are intentional, done by choice rather than as a response to vision loss.

What we notice / why we love this painting

In his earlier work, both by his own admission and as can be observed in the array of work he produced, Hollerbach experimented with various forms of abstraction. As he famously said in his oral history, available through the Vision & Art Project, vision loss “freed him from the tyranny of good vision.” He spoke often in his later years about how his inner vision and voice as an artist was one of abstraction and simplification. We can see here in this early work, reminiscent of Pablo Picasso, a searching and longing for emotional depth perhaps only achievable when suggesting what cannot be seen. Three figures exist in a shared, multi-dimensional space outside of time and place, each confronting the viewer with a presence only suggested through lines, known proportions, and familiar gestures.

Cubism in this way, and more specifically this multi-figured painting by Hollerbach, is a poetic placeholder that requires us to infer and speculate: are they old, or young? Is the figure on the right that looks directly at us disconcerted, or lost in thought, annoyed at the figures to the left, or indifferent to them? Because all three figures are rendered in white are we meant to think of race? Is the pinkish pale red that is used on the lower leg of the figure on the left meant to suggest a flaying of sorts, or does it serve simply as a way to evoke the fleshiness of the human figure in a field of otherwise non-representational color notes? Or maybe it is not conscious or intentional at all on Hollerbach’s part, with he himself allowing for the eccentricity of the unconscious to play its part.

However one interprets this multi-figured painting, in the simplest of terms we see three figures rendered in white placed confidently against an abstract background of muted red and yellow earth tones. Nothing more, nothing less.

To inquire about purchasing this painting, please contact A’Dora Phillips at aphillips.visionandartproject@gmail.com, or visit our benefit exhibition website.

10 & 11. Beach Monoprints by Serge Hollerbach

The scene

In the first of two very similar monoprints, a semi-abstract beach with four figures—three large and one small—is depicted on a rectangular sheet of paper. The larger figures are in profile, hunched over and walking on the beach toward the left side of the canvas, seemingly against a strong wind. The smaller figure walks toward the water, their back to us.

The beach is an unbroken expanse of ochre, before it meets the grey water, at a line as soft and porous as sand along a coastline. The sky stretches above, the same iron grey as the water, which makes it seem to meld into the ocean, save for a dark horizon line between the two. Clouds, darker grey, hover in the sky. Though water and sky share the same color and tone, the water is streaked with faint strands of broken white lines. These lines, composed as they are, very much evoke a series of waves coming in and retreating from the shore.

The second monoprint, pulled as it was from the same plate, displays precisely the same composition: the same four figures, the ochre sand, the ocean, horizon line, and sky. But, perhaps because Hollerbach did not replenish the paint on the plate before the second printing, the second monoprint is less saturated with paint and appears more washed out, as though the image is bleached by the sun.

What we notice / why we love these monoprints

Along with painting urban scenes, Hollerbach often turned to the beach for inspiration; it was the subject of one of the books on his work that he published during his lifetime. He especially liked depicting semi-clad beachgoers, whom he carefully observed and drew when he traveled to Southern France in the summers with his wife. But in this series of monoprints, nature is the main focal point, not the sketchily rendered figures. Not the look of nature, but its feel. Both individually and as a group, this series of monoprints evokes the transitory nature of beach experiences, ever changing, fresh and swept with peaceful vigor, blown by wind, washed by surf, adrift with clouds.

It’s amazing that Hollerbach captures so palpably on paper the sensate experience of the beach on a blustery day, a day of squalls, a day when the wind gusts, clouds move fast, the light changes, and you feel time moving, each second different from the last. He paints the kind of day when, if you find yourself on the beach, you feel a little bit more alive.

To inquire about purchasing one or more of these monoprints, please contact A’Dora Phillips at aphillips.visionandartproject@gmail.com, or visit our benefit exhibition website.

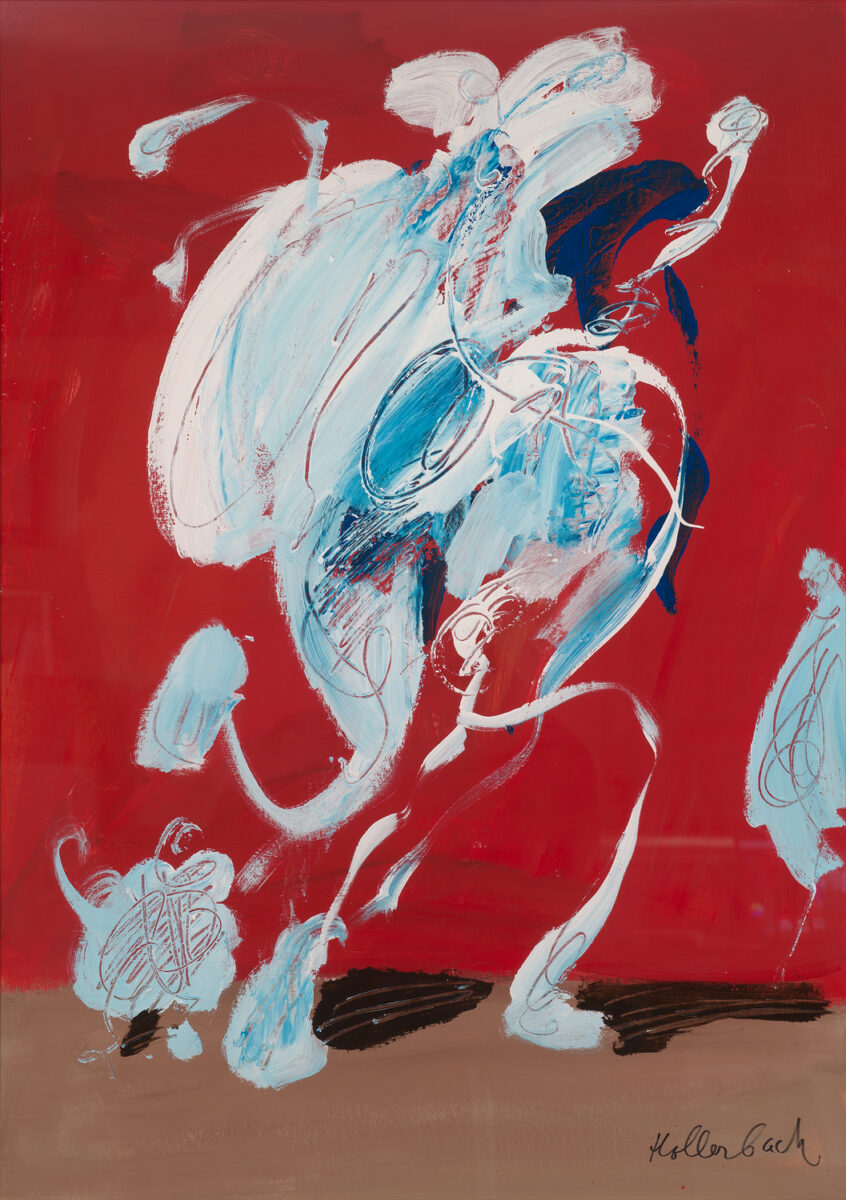

12. “Figure with Dog on Red” by Serge Hollerbach

The scene

This unique, late-life painting shows several figures energetically painted in a vigorous whirlwind of calligraphic pale white and blue brushwork, set against a deeply chromatic red background. The largest shape evokes a person seen from the side walking across the canvas from left to right, with a smaller shape behind it that appears to be a little show dog like a poodle, rendered in a fluffy, billowing mass of pale blue and white paint. From this abstract picture, images of Don Quixote come to mind, riding his horse across the landscape in search of a windmill.

What we notice / why we love this painting

As a painting, we can appreciate a sense of freedom expressed in the loose, fluid shapes. Hollerbach once commented on how, as an artist, losing his vision freed him from the “tyranny of good vision,” a fact that we can see palpably in this late-life, “post-macular” painting, one of the first in a series that he painted after losing vision to macular degeneration.

To inquire about purchasing this painting, please contact A’Dora Phillips at aphillips.visionandartproject@gmail.com, or visit our benefit exhibition website.

Leave a Comment