At 90 Years, a Life of Talent, Luck, Music, & Play

May 09, 2017

We’re celebrating the artist and illustrator Robert Andrew Parker, who turns 90 this week. Parker was the subject of the first feature we ever posted at the Vision & Art Project in 2014. After meeting him in 2014, we went on to record an oral history and make a short film about him, “A Is For Artist.”

Robert Andrew Parker is 90 years old. Though he says he feels like he is 180 or 190, in many ways, he seems ageless. A painter and printmaker, Parker still goes to his studio every day. A drummer, he still plays gigs every Saturday night. A committed pacifist, he maintains a lively interest in politics and culture. He’s understandably not happy that his drums are now too heavy for him to pack up on his own after his Saturday gigs, or that he can no longer go parachuting, or that, because of macular degeneration, he can no longer read, fish, or bike. But, to the outward observer, Parker is a rare and fortunate figure, and his extraordinary body of work feels like an inevitable and unstoppable outpouring of his spirit.

Parker’s early success: “one of the most accurate and at the same time most unliteral of painters”

Parker achieved early success in 1952, when he was included in an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Soon thereafter, he was included in exhibits at MoMA, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Brooklyn Museum.

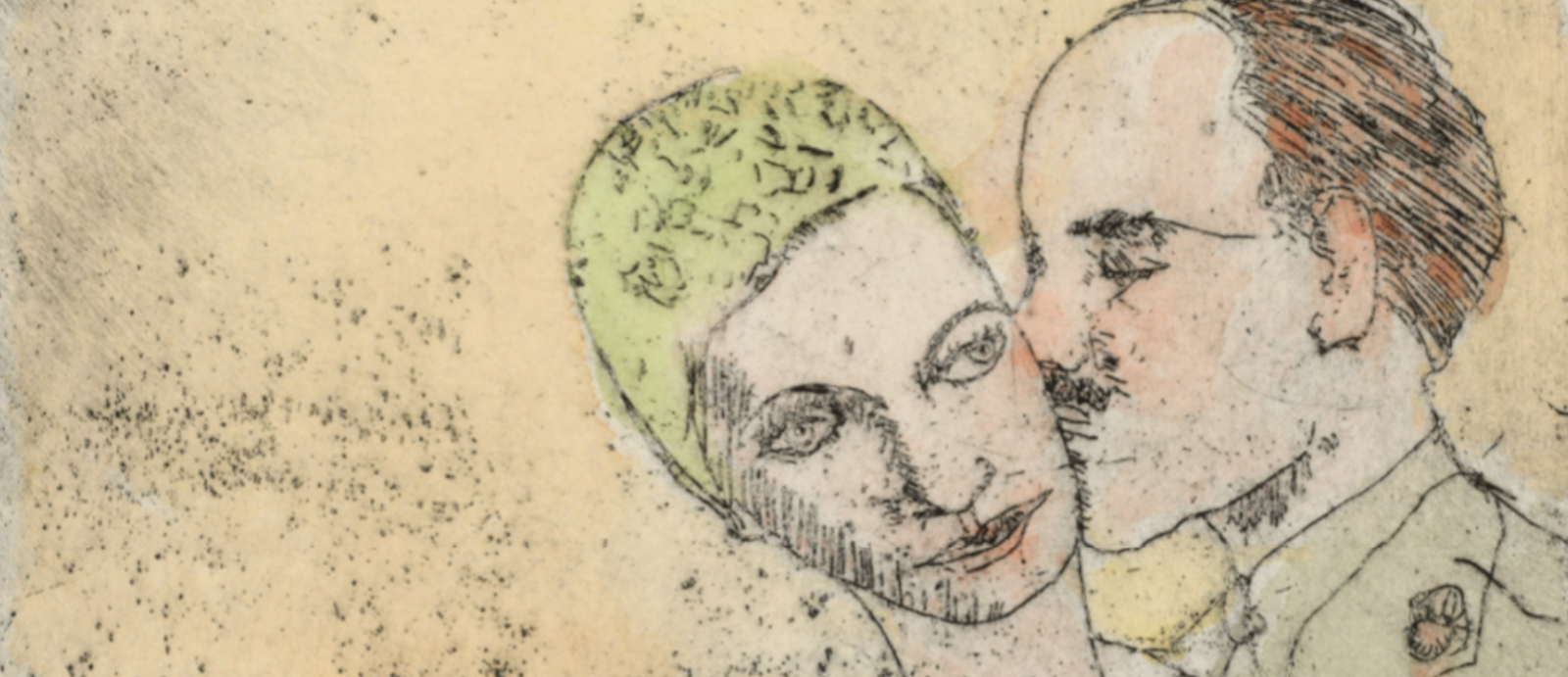

He came to the attention of Marianne Moore, who wrote: “Robert Andrew Parker is one of the most accurate and at the same time most unliteral of painters. He combines the mystical and the actual, working both in an abstract and a realistic way. One or two of his paintings—a kind of private calligraphy—little upward-tending lines of actual writing like a school of fish—approximate a signature or family cipher.”

At Moore’s behest, he illustrated a book of her poems with hand-colored etchings of animals, a favorite subject of his. And in the six decades since his prodigious debut, Parker has seen his work acquired by many important museums, including MoMA and the Met. He ‘s worked as an illustrator for The New Yorker and Time, illustrated 100 children’s books, and received several prestigious fellowships, including a Guggenheim. His creativity extends beyond his core oeuvre, painting and printmaking, into sculpture, writing, and music.

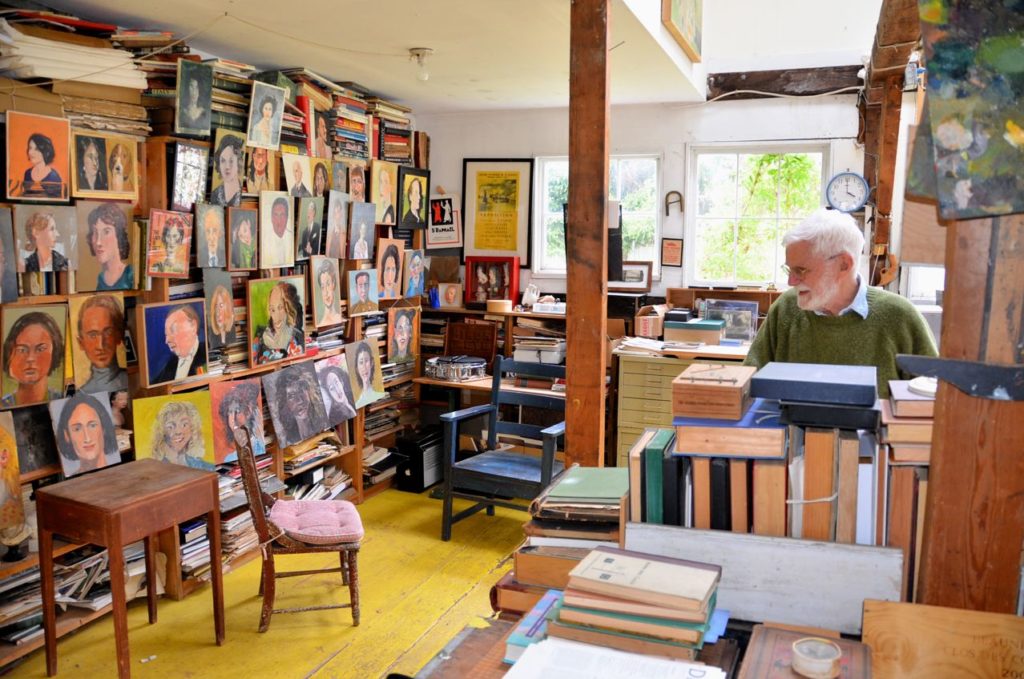

Parker’s studio—and roving imagination

To enter Parker’s studio in West Cornwall, Connecticut, is to encounter the vast creative and artistic reaches of his imagination, which expresses itself in the many subjects he’s explored over the years and the many mediums in which he’s worked.

He loves animals—he often had a dog, now has a cat, once kept a flock of sheep and a crow as pets. His flat files reveal this interest. He has hundreds of drawings and paintings depicting creatures, both real and imagined: an ink wash of his pet crow, a highly textured acrylic of a black dog running along a road, men on horseback, and life-sized monotypes of captive monkeys, whose fierce expressions are hard to avoid, and harder yet to forget. Some of his most tender and expressive images are of animals. His crow Coco, rendered in ink on paper, is proudly curious and detached. His mark-making seems to trace a caress. A flock of ephemeral butterflies, not quite within reach, look as if they are dissolving in the process of materializing.

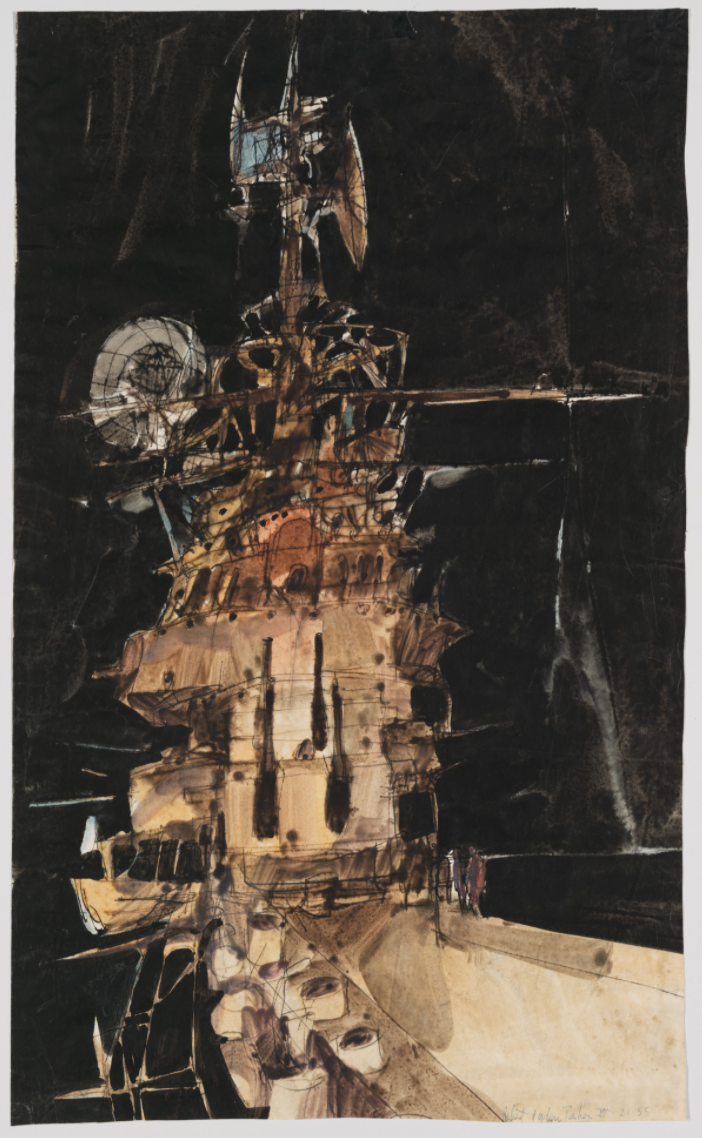

Animals are not the only subject Parker has spent his life investigating. He’s also spent his life investigating war. Images he’s created of fighter planes and battleships fill his studio, while model airplanes hang from the rafters.

Faces fascinate him, as well. His portraits are at one and the same time highly naturalistic and highly stylized.

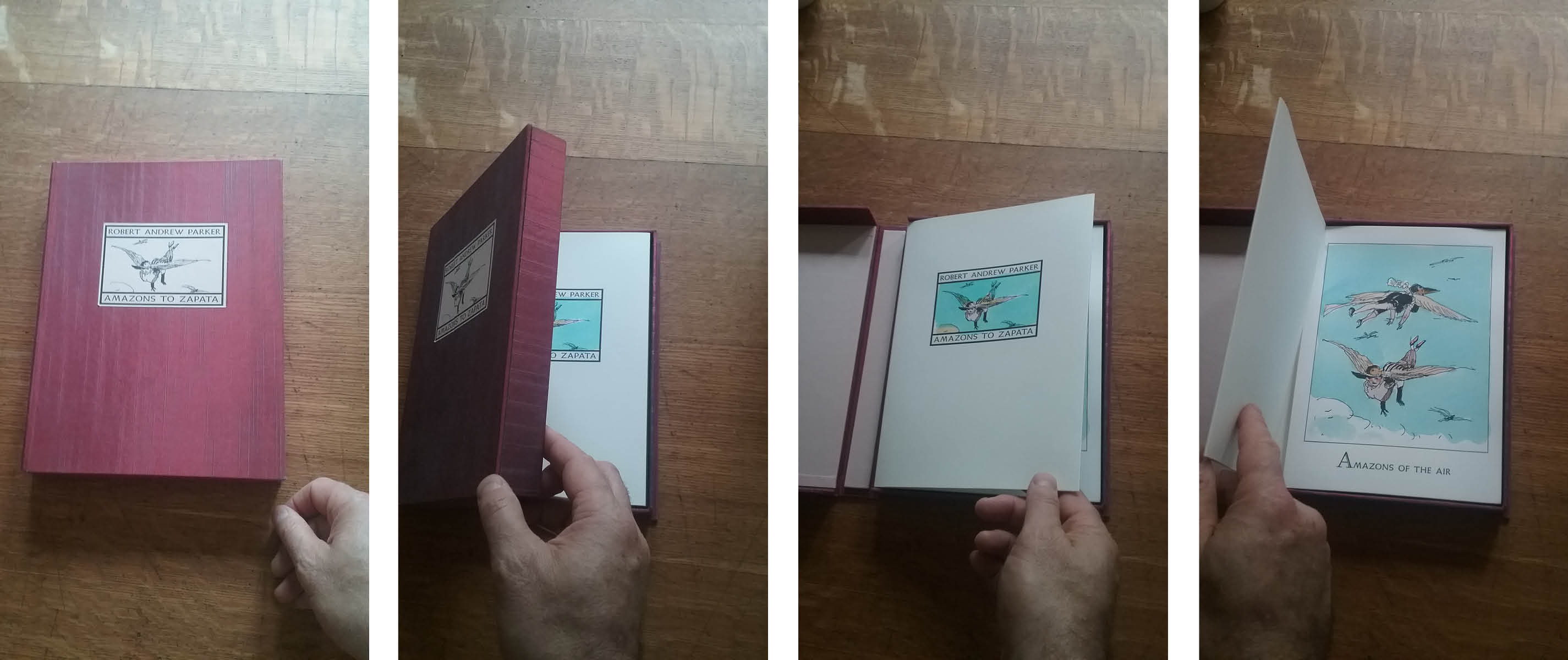

Another facet of his artwork derives from his love of literature and books, which overlaps with his prodigious printmaking skills (after obtaining a degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Parker studied printmaking at Atelier 17 in New York City). He’s made countless bound and portfolio-style books. These include alphabets, journals of dreams and travels, portraits of women writers, all collected in folios of various shapes, sizes, and mediums. Sometimes, Parker even hollows out old books he gets at rummage sales and uses them as repositories for his own visual stories. A lot of these folios showcase Parker’s humor: he’s tucked his wife’s portrait into his book of famous women authors; he likes to play with images and words in his alphabets (“A is for Avro-bison.”)

His work has many moods, darkness among them. A series 20 hand-colored etchings, titled German Humor, portray the earliest years of the Third Reich to its horrifying conclusion. Their tone ironic and style expressionistic, these deeply disturbing images turn the viewer into a voyeur and can be hard to shake.

Creating as a matter of daily life

Though Parker has often found an audience, he works without an audience in mind. He likes to work quickly, switches mediums with the seasons, experiments with techniques, plays. Winter is the time for etching, summer for sculpting (yes, he also sculpts). It’s then that the heat warms the plaster and makes it easier to work with. He doesn’t mind letting go of his work. Often, in fact, he destroys everything he’s been working on at the end of the day.

Growing up, deciding to be an artist

Born in Norfolk, Virginia in 1927, Parker’s mother was an amateur artist. His father was a dentist for the public health service. Because of father’s assignments, his family often moved.

He started on his artistic path when he was about 8 or 9 years old and contracted tuberculosis. His family lived in Detroit at the time. A doctor advised them to take up residence in a more arid climate better suited for consumptives. His father asked to be stationed in Fort Stanton, New Mexico, a nineteenth-century military reservation converted into a tuberculosis sanitarium in 1899.

It was a beautiful spot high in the Sacramento Mountains. For the first year and a half his family lived there, Parker spent most of his time in bed on the screened-in porch. Many people had been there before him—some of whom, as he was acutely aware, had died. Along with their ghosts, they’d left their books, and he got in the habit of reading. “All kinds of books,” Parker said in one of our interviews with him. “Ben-Hur, The Mysterious Stranger, The Little Minister, Kingdom Come, [The Adventures of] Tom Sawyer, all those. I read all the time for entertainment, because you couldn’t get the radio there until after dark. A lot of them were terrific. I’ve never forgotten Mark Twain’s Mysterious Stranger, the last book he wrote. It’s very strange.”

Parker’s childhood drawings forecast his artistic preoccupations

Along with reading, Parker spent his days drawing and painting. He still has one of his sketchbooks from that period, which his mother wisely kept. Because he was confined to his bed, Parker painted watercolors. (This remains, in many ways, his preferred medium and the one he is most confident of having mastered.)

Mostly what he drew back then were imaginary scenes of the Second Italo–Ethiopian war and the Second Sino–Japanese war, which he heard about on the radio. As he says of his drawings, “The Italians are always charging. Ethiopians are in robes with burnooses and everything, and the Japanese–Chinese ones are pretty rude too.” Because his mother shared his interest in art, she encouraged him and kept him well supplied with materials. He also received some early encouragement and training from a woman named Jane Hathaway, who visited Fort Stanton as an art instructor with the Civilian Conservation Corps.

As a teenager yearning to serve his country and pulling pranks

When Parker’s tuberculosis was healed, his family left New Mexico, first for Seattle, then Chicago. For a while, he lost his interest in drawing and painting. World War II had started, and it occupied his thoughts to the exclusion of almost all else.

His brother joined the Navy during the war. This left Parker alone with his parents, which he wasn’t happy about. When they moved to Chicago, he got into “all kinds of trouble.” His antics sound rather tame from a twenty-first century perspective, but at the time, his parents agonized over him. He refers to his earlier self as a “degenerate”—not entirely in jest, one senses. What did he do? He stretched wire between the desks in the science classroom and a teacher tripped; his grades were awful; he was “fired” from the band. The last straw, he threw an ice ball at the school principal and was expelled from high school. “It was like a cartoon,” he says. “It hit him in the head and knocked his hat off, and he said, ‘Who is that?’ I mean, that was it. I wasn’t suspended or anything, just get out.”

These stories make me think of the Parker I’ve seen, using a catapult at 89 to fling apples into his next-door neighbor’s yard and playing around in his art, fashioning a small head in plaster and adding it to a painting, or making altars out of found objects. But as a high-schooler, when his sense of play led to expulsion, he was sent off to live his grandparents and finish school in Delphi, Indiana.

The Army Air Corps, art school, a growing family

Parker yearned to enlist in the military like his brother. He tried to get in before he was 17 with a ruse (family Bible, missing birth certificate), but it didn’t work. As soon as he graduated from high school, though, he joined the Army Air Corps. The war ended two weeks later, and so he never saw combat. Still, he had to remain in the service for a few years and considers himself a veteran.

When he left the Army Air Corps in 1948, he had to choose a profession. Art was the inevitable path, it seemed, even though music enthralled him, and he had played the clarinet in the Army Air Corps. He enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago on the GI bill. While still a student, he married his first wife. Two of their five sons were born in quick succession.

He wanted to move to New York, “where the art was.” When he graduated from the Art Institute in 1952, he and his young family did just that. He got a job that he would come to detest as an art instructor at the New York School for the Deaf. After teaching during the day, her developed his printmaking skills at night at Atelier 17.

Making tomato soup out of water and ketchup

Parker and his family were living in Yonkers then. He remembers hitchhiking to the first L stop at Woodlawn and Jerome Avenue in the Bronx. He’d then take the subway to Eighth Street, near where the atelier was. To illustrate how poor he and his friends were, he talks about making “tomato soup” out of ketchup and hot water at a diner near Atelier 17. “One guy would buy something and there was ketchup on the table. The rest of us would get hot water and put ketchup in it and have tomato soup.”

He yearned to be closer to Tenth Street, then the center of the New York art world. After two years in Yonkers, he found an apartment on Tenth Street. Before moving there with his family, though, he “lost his nerve,” he says. “I thought, I can’t imagine a three-year-old and a two-year-old on these stairs and the rickety building, and I said, ‘No, forget it, I’ll do another year at the deaf school.’”

A big break: playing Vincent Van Gogh’s hands in Lust for Life

Though Parker was only twenty-eight in 1955 and had already experienced some enviable success as an artist, he felt trapped. In an unexpected turn of luck, Parker was hired by MGM to make the drawings and paintings on the set of the Vincent Van Gogh biopic Lust for Life. Thanks to a referral by a well-known art historian connected to MoMA, MGM called him to have him audition his hands and, after an interminable wait, they called again to ask if he could go to Paris a few days later. He went into Manhattan, signed a contract, and flew to Paris.

It transformed his life. From then on, he made a living from as an artist and illustrator. He also taught at schools like the Rhode Island School of Design, Parsons School of Design, and the School of Visual Arts.

Fast forward half a century

One day in the studio folded into the next and, in a kind of shock to Parker, he’s ninety. With his ever perpetual motion, he continues to explore the subjects and themes that have always interested him, yet without ever seeming to replicate his past achievements. His life’s work is in many ways an extended series of ever-fluctuating reflections on great passions that reach back to his childhood. Though this work is often done quickly, it reveals the beauty of deep and sustained attention.

This article is based on our oral history with Parker, which you can find here.

In honor of Parker’s birthday, The David M. Hunt Library in Falls Village, CT will host a special exhibition. Beginning with a birthday reception on Saturday May 14 from 3PM to 5PM, the retrospective of paintings, drawings, etchings, and books will be on display during the library’s operating hours through July 2.

Further Reading

Robert Andrew Parker

Robert Andrew Parker, Artist of the Mystical and Actual, Has Died

In our short film from 2017, which was shot when the artist was in his mid-eighties, Parker talks about his life.

Read More

Comments

A great piece and great photographs of my father and his work. Thank you for this.

We continue to enjoy the quality work of the authors of The Vision and Art Project, most recently this engrossing piece on the occasion of the 90th birthday of Robert Andrew Parker. Well done!

A remarkable man and a great review of his indomitable spirit. Thank you.

I remember the first time went to Tony’s (Robert’s son [one of the many, they all play drums, to a high degree, I might add]) to play music with him. There was a print of a saxophonist on his son’s wall, It jumped out at me. There was “something” about it. I’ve never met the man, but the fruit that has fallen by that tree…..

I have known Bob since the middle 60’s. His brother and wife were dear friends of ours and his visits to Indianapolis were ones we

all looked forward to. What a treat to come upon this article about him.I will always remember the times together and wish him well.

Great article! Some things I still didn’t know about my Dad until reading this and I want to now read Mysterious Stranger by Twain immediately ! Cheers!

I know this piece is a few years old, but I recently re-read it. Bob is my great uncle, his older brother Bill was my grandfather. I haven’t been able to spend as much time with him as I would like because of the distance between us. Working in an art museum now, I’ve come to really appreciate his work as an artist. When I was growing up, I just thought it was neat that Uncle Bob was a painter and did lots of illustrations for kids books. (I had such a joy reading then with my grandpa whenever we received the latest in the mail) Now, as an adult, I really appreciate the artwork that he’s created and the experiences that shaped his outlook as an artist. Thank you for this article.

It has been such a great pleasure to work with Bob. Thank you so much for taking the time to share your experience.

What a lovely piece. And what a surprise.

I was a neighbor kid living in the nearby home of Tom Allen when the family lived in Carmel NY and have fond memories of everyone. Dottie was especially kind to me ( I babysat a few times).

I have followed Bob’s work over the years along with the rest of the gang of illustrators and painters from that era. I think he’s the last one standing at this point. And doing well!

Thank you so much for reaching out. Bob is wonderful, and we feel so lucky to know him!

I had the honor of showing Robert Andrew Parker’s art at my gallery, The Almquist Gallery, in New Preston, Connecticut. His fabulous jazz band played at a number of my openings. I remember one etching in his Third Reich series in particular portraying many pairs of eye glasses. It contained all the horror. A high point of my friendship with Bob was an evening when he came to my tiny home and painted my portrait. It hangs in my living room. Bless you Robert Andrew Parker, and Happy Birthday. With love, Jennifer Almquist and Tom Fahsbender, Norfolk, Connecticut

Got to see your wonderful art work and hear Jazz by Five play at Music Mountain many times because I was a good friend of the late Louise King. I boarded her horse at my stable and we made clay horses together at WAA. Just today I realize we share the same birthday of May 14! You have a few decades on me, but whose counting! Regretfully won’t be able to make your celebration because of family plans for my own. Blessings and enjoy! 🤗

Bob,

Congratulations on your birthday! Myrna and I have your painting in our living room and think of you every day. I remember visiting you and your family—was it Carmel?— and your bb-gun wars. I enjoyed your visits out to Sag Harbor and hope for a chance to see you again soon.

All the best to you and yours,

Paul

Hi Bob-it seems I am a late arrival to this party. I enjoyed seeing the film and photos. I still have one of the watercolors that you gave Jim Gardner and a cassette tape recording of one of your radio shows. I live in Virginia now with my daughter Pannonica. All my love to you and Judy.

I played piano in a band where Bob odrums.

One of my favourite of his images is his design for cover of The Charterhouse of Parma.

Leave a Comment