Manet / Degas

October 15, 2023

Currently on view at The Met through January 7, Manet/Degas tells a story of novelistic depth about a complex friendship and rivalry that led to one of the most significant artistic dialogues of modern art and ends (sort of) with Manet’s death and Degas’s blindness

Common biographical threads

As the exhibition Manet / Degas sets out, many of the details of Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas’s biographies run in striking parallel. Manet was born in 1832; Degas in 1834—both in Paris, both to affluent families. Manet took up a failed apprenticeship as a sailor before studying painting at the studio of Thomas Couture, a French history painter and teacher. Degas studied law before training as a painter at, among other places, the famed École des Beaux-Arts. As part of their independent studies, both men traveled extensively in Italy in the 1850s, immersing themselves in masterpieces of European art, many of which they copied. Reputedly, they met at the Louvre in the early 1860s. Degas was making an engraved copy on a copper plate of a Velázquez’s painting, Infanta Margarita, which impressed Manet, since he was interested in the painting, too. For a few years, these two men, bound additionally by patriotic fervor during the Franco-Prussian war (1870–1), socialized regularly. But if their friendship started out as a relatively straightforward affair, it quickly became complicated and not altogether amicable. The complexities of their friendship—their romance of meeting and then diverging and coming together again (albeit after Manet’s death)—and what it contributed to the history of modern art—are the subject of this exhibition.

Differences and divergences

For all the common threads of their experience, Manet and Degas approached life and art differently and were to move in different circles as their careers progressed. Temperamentally, Degas was solitary and had a reputation of being somewhat ill-tempered; Manet was sociable and known for his open affability. Artistically, when Impressionism was still considered dissident, Manet, though his paintings were thoroughly modern, distanced himself from the movement. Not so Degas. At the historic first Impressionist exhibition of 1874, Degas exhibited ten works. Manet refused to participate and instead submitted his paintings to the Salon, which had dictated the definition of art for over two centuries in France and whose dominance the Impressionist exhibition was meant to subvert. Ultimately, both men would engage Impressionism on their own uniquely individual terms.

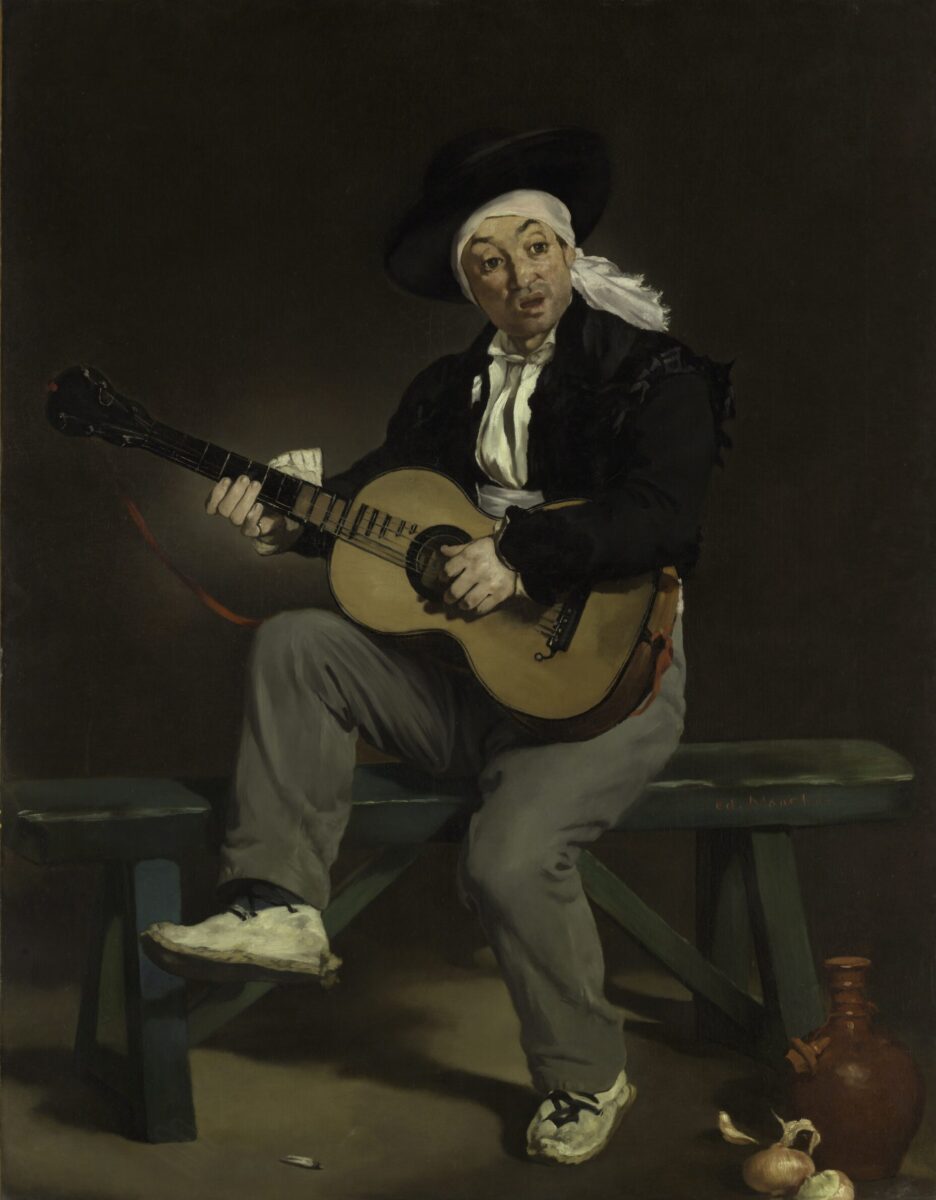

As shown by their early work, a generous—and fascinating—selection of which is on display, both artists were breathtakingly talented from the outset. That said, Manet’s career took off first. His paintings, such as Le Chanteur espagnol (The Spanish Singer) received attention at the Salon in the early 1860s. Whereas Degas’s paintings, such as his reimagining of the ballet “La Source” as a historical scene (the first painting he was to do on the subject of ballet), went unnoticed. Manet’s work as a young artist often appears more confident and self-assured than Degas’s, whose work seemed more tentative. Yet as their careers progressed, Degas’s unique vision—the complex interplay of shapes and compositions—took on a quiet power next to Manet’s vibrant canvases, a fact that was recognized during their lifetimes, as Degas’s reputation grew to equal Manet’s.

Shared subject matter

Despite the obvious differences between them, both men often painted the same types of scenes. Their overlapping work—sometimes seeming to move in parallel, sometimes to veer in different directions— provides the organizational scaffolding of this exhibition and an opportunity to explore in some depth their synchronicities and divergences. Side by side hang their respective early self-portraits and family portraits, their copies of masterworks, the genre paintings they made for the Salon, their portraits of society women, of the horse races, nudes, and Parisian scenes, especially those centering upon women (Paris’s singers, prostitutes, laundresses, milliners). They made work within miles of one another in their Paris studios, of similar subject matter, for more than two decades of a friendship that involved “stories, disagreements, and reconciliations,” say Stéphane Guégan and Isolde Pludermacher, two of the four curators. The work they made that shared, as their lives did, so much, yet was utterly different.

Given all that connected and divided them, it was “inescapable,” as the curators say, that Manet and Degas were to become artistic rivals. Though what artistic rivalry may be—neither good nor bad, perhaps, but merely an inevitable spur to creation—is one of the many questions of this exhibition. “They both looked at each other a lot and were very much nourished by each other’s art,” said Pludermacher to Theo Farrant of Euronews.

The exhibit raises many questions about the two men, their relationship, and their work

Their friendship / rivalry is the stuff of novels, and, in delving into the lives and work of these two men Manet / Degas works as a good novel does to empathically draw us into their psychologies, temperaments, aspirations, struggles, successes, and failures, which greatly enriches the exhibition and the viewer’s ability to deeply engage the incredible work that is on display. Like a great novel, the exhibition eschews simplicity. For example, while it sees ease and appreciation in Manet’s portrayals of women and something “troubled” in Degas’s, it cautions against assuming that Degas must necessarily have been misogynistic. In keeping with its novelistic approach, the exhibition traffics in questions, mysteries, secrets, and ambiguities as it brings us to these men’s ends: Manet, dead at 51 of complications from syphilis; Degas continuing on for more than three decades as his sight worsened and he became blind. It hints at things that cannot be known, only surmised and imagined.

In the late 1860s, for example, when the two men were on more explicitly friendly terms, Degas drew and painted Manet several times, though Manet appears not to have ever done the same of Degas—why? Why, too, did Manet cut his wife out of Degas’s painting Monsieur et madame Édouard Manet (1868–69)? He was said to have done so because he didn’t like Degas’s portrayal of her, but the act hints at the tumultuous undercurrents of their friendship. Did Manet truly “rob” Degas of some of his subjects, as Degas contended, after Manet’s death? (Pludermacher thinks not. “Manet absorbed everything that had been done before him so as to produce something new,” she told the Wall Street Journal.)

Manet’s death, Degas’s blindness

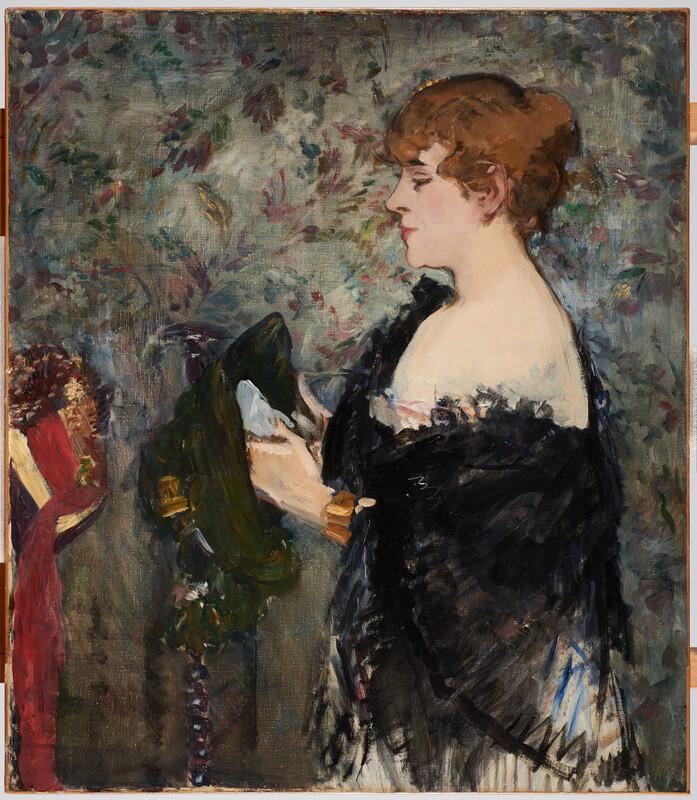

For both men, lives that begin with the expansiveness of youthful talent close with the limits of the body. It hits like the unexpected demise of a beloved character when, near the end of the exhibit, we learn amid Manet’s vivid paintings of the time—jots of color—that he has died after the amputation of a gangrenous foot. In ending with his death, the exhibit evokes the reality of Manet’s body, yet leaves unspoken the certainty that his embodied experience played a role in his artmaking, that in the last years of his life, as he painted gorgeous works such La modiste (1881, of a milliner, a subject Degas also treated at about the same time), he was in agonizing pain and grappling with mortality.

Just as Manet had been living with a serious illness for many years, one that must certainly have affected his art, so Degas’s eyesight had been steadily declining from the time of the Franco-Prussian war. In letters to friends and family throughout the 1870s, he not infrequently discusses the “trouble” with his eyes, including “a spot of weakness” and “sensitivity to light.” When he traveled to New Orleans in 1872, he couldn’t endure painting under the brilliant outer light there because of that photophobia. “What lovely things I could have done, and done rapidly if the bright daylight were less unbearable for me,” he wrote to James Tissot in 1873. “To go to Louisiana to open one’s eyes, I cannot do that. And yet I kept them sufficiently half open to see my fill.”

He painted what he could, such as two of the great works in the Manet / Degas show—his interior scene of Cotton Merchants in New Orleans and his outdoor scene, Children on a Doorstep, rendered by the artist from a perspective that sheltered him from the brightness of the sun. By 1877, Degas was experiencing “a cloudiness” in his vision. And when Manet died in 1883, Degas had a blind spot, which obscured what he fixed his gaze upon. One wonders what the men knew of one another’s struggles. If Manet knew, for example, that Degas’s decision to hide the details of faces in the paintings he began making in the 1880s may have been because it was beyond him to see them.

After Manet’s death, Degas reunited Manet’s painting, L’execution de Maximilien

Degas was shaken when Manet died. At Manet’s funeral he lamented that “Manet was better than we knew,” and over the years until his own death in 1917 Degas bought more than 80 of Manet’s paintings, which he planned to display at a museum he dreamed of opening. He also acquired and partially reunited fragments of an unusually large painting by Manet, the second version (of three) of L’execution de Maximilien, now in the National Gallery in London. Because of its controversial, political subject matter, the painting was seen as highly subversive and never exhibited during Manet’s lifetime. As it sat in Manet’s studio over the years, the left side of the painting became damaged and was cut away. After his death, his family cut additional segments off the painting. Degas went to great lengths to track down fragments to bring them together again.

This painting’s jigsaw-like appearance, its intensity, the visible traces on it of a complex and fragile life is a fitting coda to Manet / Degas, to Manet and Degas, and to Manet and Degas’s friendship.

Information about the exhibition

The exhibition, which runs through January 7 at The Met, originated at the Musée d’Orsay.

Curated by: Isolde Pludermacher, General Curator of Paintings, Musée d’Orsay; Stéphane Guégan, Scientific Advisor to the President of the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée de l’Orangerie; Stephan Wolohojian, John Pope-Hennessy Curator in Charge, Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and Ashley E. Dunn, Associate Curator, Department of Drawings and Prints, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Comments

Thank you for this in-depth description of Manet and Degas style of painting and their relationship to each other. While, in undergraduate studies, I took every art history classes as electives. I learned so much more through art history than general history classes, and I am grateful. Thank you very much. I enjoy reading about the intricacies of impressionist and impressionist.

Leave a Comment