Edgar Degas’s Correspondence

April 17, 2016

Edgar Degas was a copious letter writer. Here we look at his correspondence through the lens of his struggle with vision loss, and couple this chronology with examples of the paintings and drawings he produced at each stage of his vision deteriorating. (Quotes excerpted from Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas Letters, edited by Marcel Guerin.)

1870: Degas realizes the vision in his right eye is impaired

At the age of 36, Edgar Degas (1834–1917) realizes that the vision in his right eye is severely impaired when he closes his left one during rifle practice in the Franco-Prussian War and the target disappears. He attributes his eye affliction to the extreme nighttime cold in the studio where he slept during the Siege of Paris. Two years earlier, however, his cousin Estelle Musson had gone blind due to early onset macular degeneration, an eye disease with a hereditary component. It is now thought that Degas suffered from this ailment, as well.

1871: Can’t work for three weeks due to “a spot of weakness” in his eyes

In a letter dated September 30 to his friend James Tissot, Degas complains of eye problems. “I have just had and still have a spot of weakness and trouble in my eyes. It caught me at Chateau by the edge of the water in full sunlight whilst I was doing a watercolor and it made me lose nearly three weeks, being unable to read or work or go out much, trembling all the time lest I should remain like that.”

1872: New Orleans: “What lovely things I could have done if the bright daylight were less unbearable for me”

Degas visits relatives in New Orleans. Before leaving France, his family expresses concern about the “weak” state of his eyes and his need to be careful with them.

Once he is in New Orleans, Degas writes to his friend Lorenz Frølich in late November: “My eyes are much better. I work little, to be sure, but at difficult things.” And to his friend Henri Rouart in December: “The light is so strong that I have not yet been able to do anything on the river. My eyes are so greatly in need of care that I scarcely take any risk with them at all.” And, finally, to Tissot in February 1873: “What lovely things I could have done, and done rapidly, if the bright daylight were less unbearable for me. To go to Louisiana to open one’s eyes, I cannot do that. And yet I kept them sufficiently half open to see my fill.”

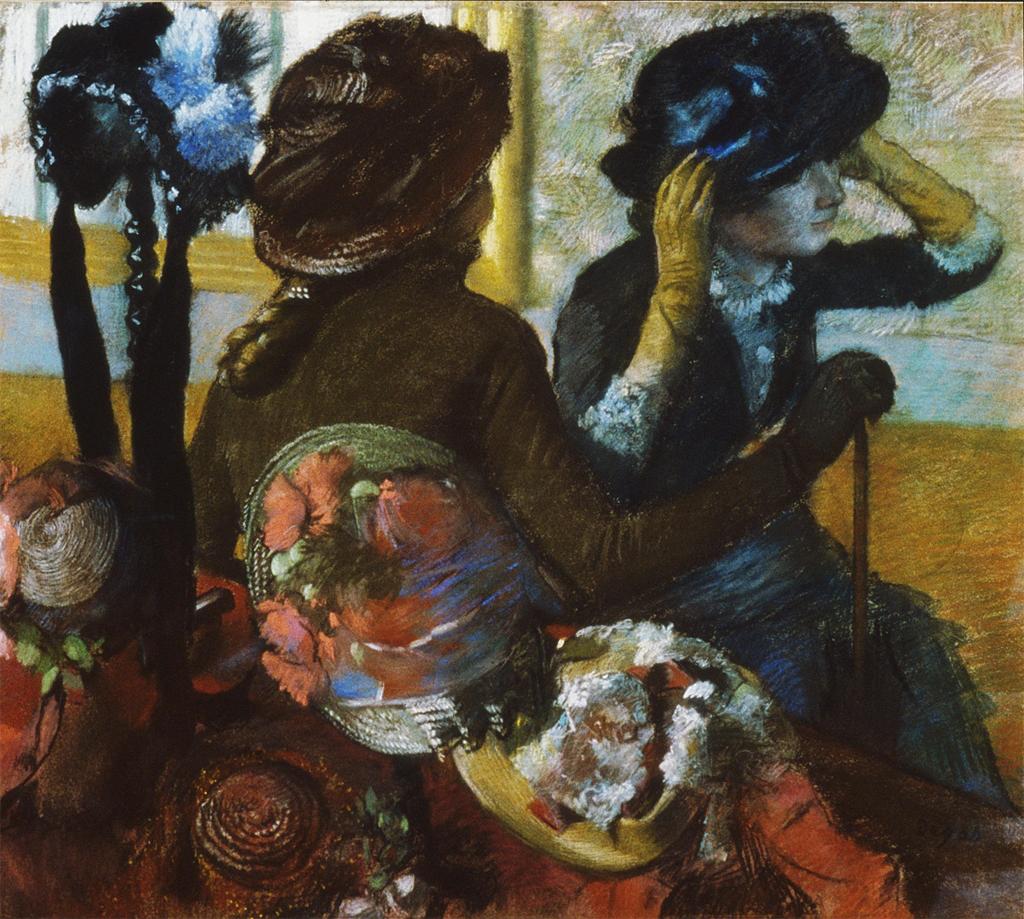

1877: A light cloudiness develops in Degas’s eyes

Throughout the 1870s, Degas not infrequently laments the state of his eyes in letters to friends. In 1873, for instance, he writes to Tissot: “This infirmity of sight has hit me hard. My right eye is permanently damaged.” And in 1874: “My eyes are sometimes quite good, sometimes bad. I am pretty much of a null… Ah! If I had my old eyes.”

Based on what Degas mentions in his letters, his primary symptoms have remained steady since first surfacing and involve poor visual acuity in his right eye and extreme sensitivity to light. The ophthalmologist Michael F. Marmor, who has studied Degas’s eyesight extensively, speculates in his book, Degas Through His Own Eyes, that in 1877, Degas’s eye disease developed beyond these initial symptoms, and he began to see a light cloudiness in front of his eyes.

1883: Blind Spot

By the time Degas meets the English painter Walter Sickert, he suffers from a blind spot, which Sickert writes movingly about when he eulogizes Degas for Burlington Magazine in 1923: “It was natural that, during the years when I knew [Degas], from ’83 onwards, he should sometimes have spoken of the torment that it was to draw, when he could only see around the spot at which he was looking, and never the spot itself.”

1884: In many letters to friends, Degas worries about his worsening eyesight

To Henry Lerolle (August 21): “Whatever I was doing, whatever I was prevented from doing, in the midst of all my enemies and in spite of my infirmity of sight, I never despaired of getting down to it some day.”

To Paul Durand-Ruel (October): “What lovely country. Everyday we go for walks in the surroundings, which will finish up by turning me into a landscapist. But my unfortunate eyes would reject such a transformation.”

To Henri Rouart: “Really it is too much, so many necessary things are lacking at the same time. In the first place my sight (health is the first of worldly goods) is not behaving properly. Do you remember saying one day, we were speaking of someone I cannot remember whom, who was growing old, that he could no longer connect, term applied in medicine to impotent brains. This word, I always remember it, my sight no longer connects, or it is so difficult that one is often tempted to give it up and to go to sleep for ever.

“It is also true that the weather is so variable; the moment it is dry I see better, considerably better, even though it takes some time to get accustomed to the strong light which hurts me in spite of my smoked glasses, but as soon as the dampness returns I am like today, my sight burnt from yesterday and broken up today. Will this ever end and in what way?”

1888–90: Visits Lourdes for a “cure”

In August 1888, Degas goes to Cauterets and Lourdes for his first of a number of “cures.” In 1890, he writes to Paul-Albert Bartholomé (August 24) about the spectacle of the sick and the pilgrims on his journey and concludes that with his “bad eyes” he has “missed everything you would have seen.”

His letters this year show his vision worsening to the point where he is struggling to read, with a corresponding tone of heightened worry, anger, and despair.

To Bartholomé (August 28): “I had much difficulty in reading the few penciled thoughts that came from Dienay with the portrait of Carnot.”

To Rouart (September 11): “I have seen some very beautiful things through my anger, and what consoles me a little, is that through my anger I do not stop looking.”

To Evariste De Valernes (October 26): “I was or I seemed to be hard with everyone through a sort of passion for brutality, which came from my uncertainty and my bad humour. I felt myself so badly made, so badly equipped, so weak, whereas it seemed to me, that my calculations on art were so right. I brooded against the whole world and against myself… I found in you again the same vigorous mind, the same vigorous and steady hand, and I envy you your eyes which will enable you to see everything until the last day. Mine will not give me this joy; I can scarcely read the papers a little and in the morning, when I reach my studio, if I have been stupid enough to linger somewhat over the deciphering, I can no longer get down to work.”

1891: Degas loses the ability to read

He begins treatment under the famous Swiss ophthalmologist, Edmund Landolt.

To De Valernes (December 6): “I see worse than ever this winter, I do not even read the newspapers a little, it is Zoe, my maid, who reads to me during lunch. Whereas you, in your rue Sadolet in your solitude, have the joy of having your eyes… Ah! Sight! Sight! Sight! My mind feels heavier than before in the studio and the difficulty of seeing makes me feel numb. And since man, happily, does not measure his strength, I dream nevertheless of enterprises; I am hoping to do a suite of lithographs, a first series on nude women at their toilet and a second one on nude dancers. In this way one continues to the last day figuring things out. It is very fortunate that it should be so.

To Halévy (August 1): Tomorrow I have an appointment at 5 o’clock with the oculist Landolt, who will not, I think, keep me late enough to prevent me from arriving at the Gare du Nord in time for the 6:25.

1892–95: Degas starts to use assistive devices

Degas’s poor eyesight becomes more apparent to others, as he begins to wear a strange contraption meant to strengthen his eyes and uses a magnifying glass to try, unsuccessfully, to read on his own. He also needs the magnifying glass to see artwork.

1893, to Valernes (undated): “…I am dreading a stay in my room, without work, without being able to read, staring into space. My sight too is changing, for the worse. I am pitying myself, so that you may know that you are not the only unhappy person… With regard to writing, ah! my friends can scarcely count on me. Just imagine that to re-read, re-read what I write to you, would present such difficulty, even with the magnifying glass, that I should give it up after the first lines.”

1893, to Valernes (Saturday): “You will see me with a comparatively ominous looking contraption over my eyes. They are trying to improve my sight by screening the right eye and only allowing the left one to see through a small slit. Things are fairly all right for getting around, but I cannot get accustomed to it for working.”

1895, to Alexis Rouart (undated): Wednesday morning I left everything to look by daylight, with a magnifying glass, and for a long time at the magnificent Gavarnis that you gave me.

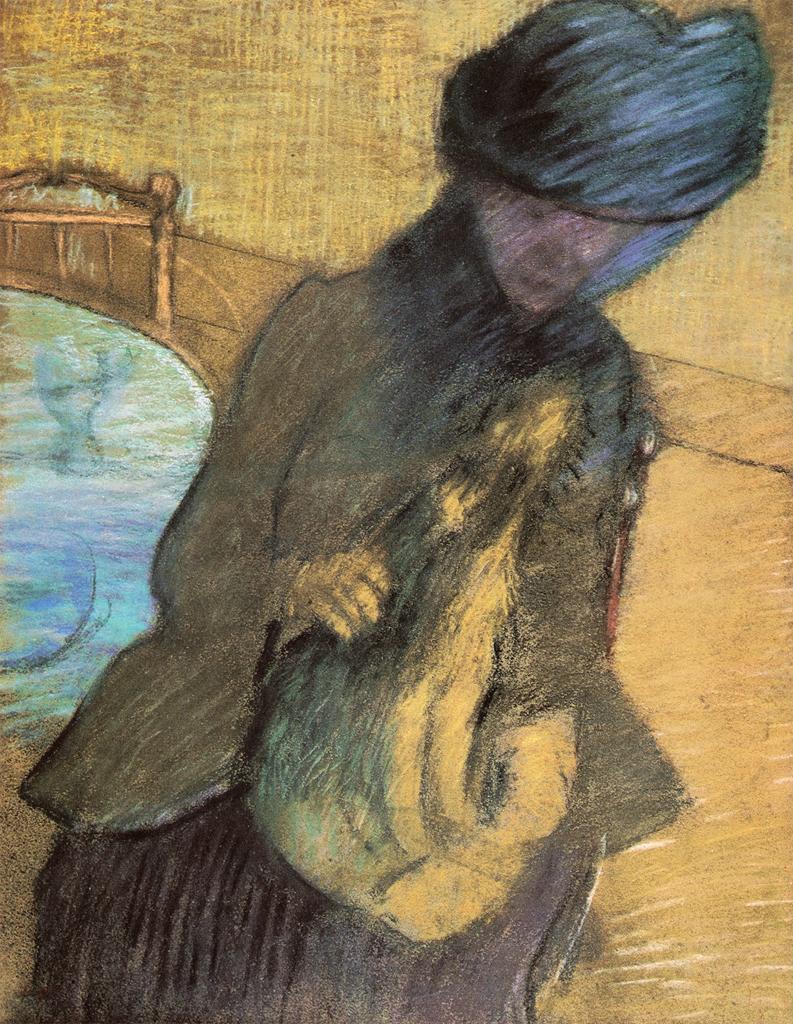

1896–7: Blind

By now, Degas refers to himself as being blind and turns to other people’s eyes as a way of accessing both visual images and written texts.

To Alexis Rouart (July 28): “Everything is long for a blind man, who wants to pretend that he can see.”

To Bartholomé (August): “Your eyes, your lights I mean, I should like to count on them… My sight is getting decidedly worse, and I am having some rather black thoughts about it.”

To M. Le Maire de Montauban (August 16, 1897): “With reference to our interview, you wish me to write you a resume of it. In view of the bad state of my eyes I am forced to be much briefer than with my tongue.”

To Madame Ludovic Halévy (November 15): “In the evenings, very nearly every evening, I listen to Zoe who falls asleep whilst reading to me.”

1903-1912: Last signed works, last letters

In 1903, Degas produced his last dated work, The Sao Paulo Bather. However, he continued to work, since in 1907, the collector Etienne Moreau-Nelaton describes seeing Degas “fencing” with a pastel.

Though he was to live until 1917, Degas’s wrote his few last letters to friends in 1910. They were short, no more than three or four lines in length. His letter dated August 21, 1908 to Alexis Rouart opens with, “Do not be angry with me, my dear friend, for replying so late to your good (sic). Soon one will be a blind man.” His last letter, dated November 3, 1910, also to Rouart. Its closing line: “I do not finish with my damned sculpture.”

In 1912, his studio and living quarters at rue Victor-Masse are demolished and he is forced move. That same year, he visited the retrospective exhibition of Ingres’s work and was seen stroking the canvases with his fingers.

1914: Sculpture

Ambroise Vollard says that Degas is still drawing. Visitors to his studio, models, and friends, describe him constantly at work on sculptures. Vollard writes of what he witnesses of Degas’s late-life working practices: “The next day I found the dancer once again returned to the state of a ball of wax. Faced with my astonishment, Degas said: ‘You think above all of what it was worth…,’” which was little in Degas’s mind beside the pleasure of starting over.

Comments

connect – relier? his words ‘Do you remember saying one day, we were speaking of someone I cannot remember whom, who was growing old, that he could no longer connect, term applied in medicine to impotent brains. This word, I always remember it, my sight no longer connects, or it is so difficult that one is often tempted to give it up and to go to sleep for ever.´’ Moved to read of his failing sight,as I an artist who draws obsessively gradually lose sight in one eye aftermath of shingles, but keep depth vision and continue to work