Lennart Anderson’s Generative Doubt

October 17, 2021

The New York Studio School is hosting Lennart Anderson: A Retrospective (October 18–November 28, 2021). Included in the exhibition are 35 works spanning a period of over six decades. Curated by Graham Nickson and Rachel Rickert in collaboration with the artist’s estate, the exhibition brings together Anderson’s paintings of the human form, still life, portrait, landscape, and streetscape. The portraits in the exhibition (and its accompanying catalog), which we consider below, embody the spirit of inquiry, uncertainty, and doubt that animated the painter’s approach to artmaking.

For Anderson, painting was akin to magic

It was 1964 when Lennart Anderson bought the Park Slope brownstone that was to remain his home and studio for the rest of his life. He would have been thirty-seven at the time and had emerged fully from his years of art training. He’d received a Prix de Rome a few years earlier and had had his first solo exhibitions, one at the historically-significant Tanager Gallery in 1962 and one at the Graham Gallery in 1963.

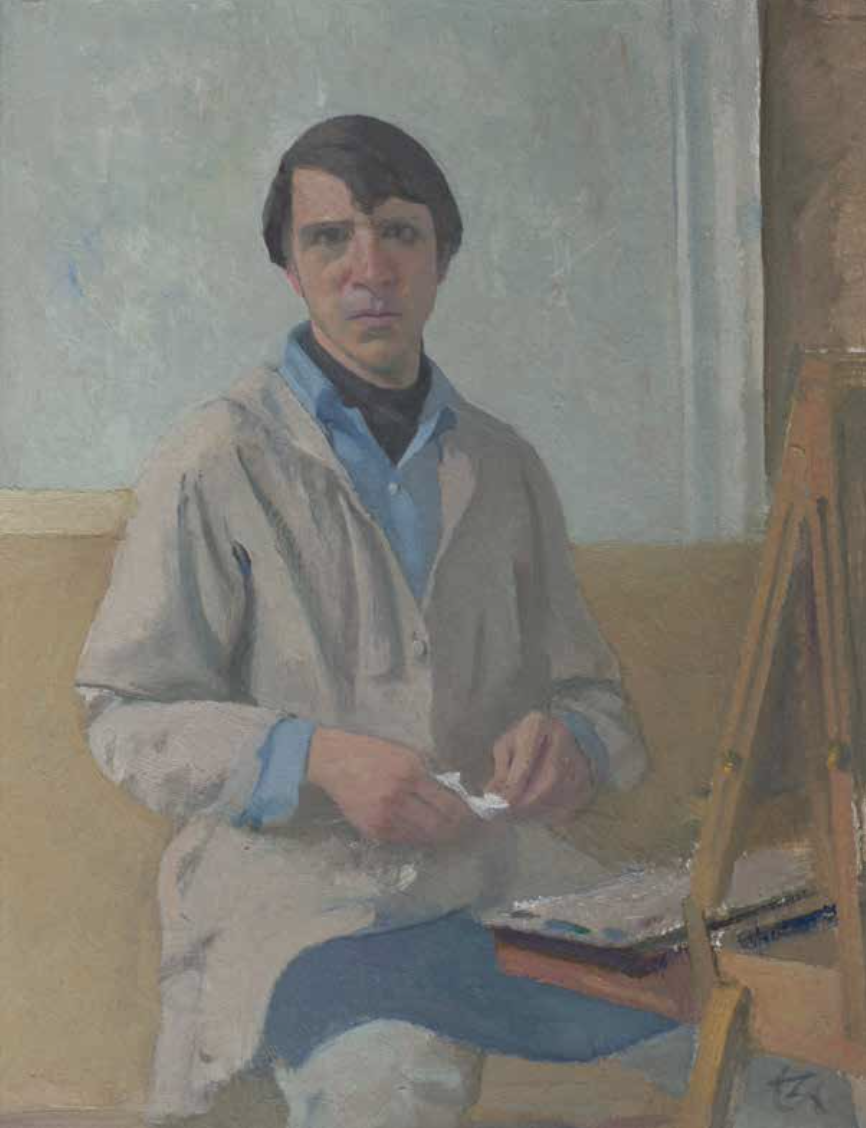

The year he bought his brownstone, he painted a self-portrait. It is included in the catalog that accompanies the New York Studio School’s retrospective of Anderson’s work. Although his career was going well, he does not look, as one might expect, sure of his footing. He looks worried, concerned. Aware of the gravity of what he’s set out to do. Aware that (historically, at least) painting was akin to magic and could change the world. But that to reach that level of achievement was not an easy task.

I don’t know if Anderson painted this particular self-portrait in his new Brooklyn brownstone, since after purchasing the property, the one modification he made was to install a skylight on the third floor to let in the steady north light that had been sought after by centuries of artists before him. Not until he created a chamber where the light would remain relatively constant and unchanging throughout the day, day after day, year after year, did he settle in to paint with, as he said, “light’s blessing.” He painted with past masters in attendance, surrounded by monographs open to reproductions of Velázquez and Titian, Ingres and Degas.

Portraits—“heads,” as Anderson called them

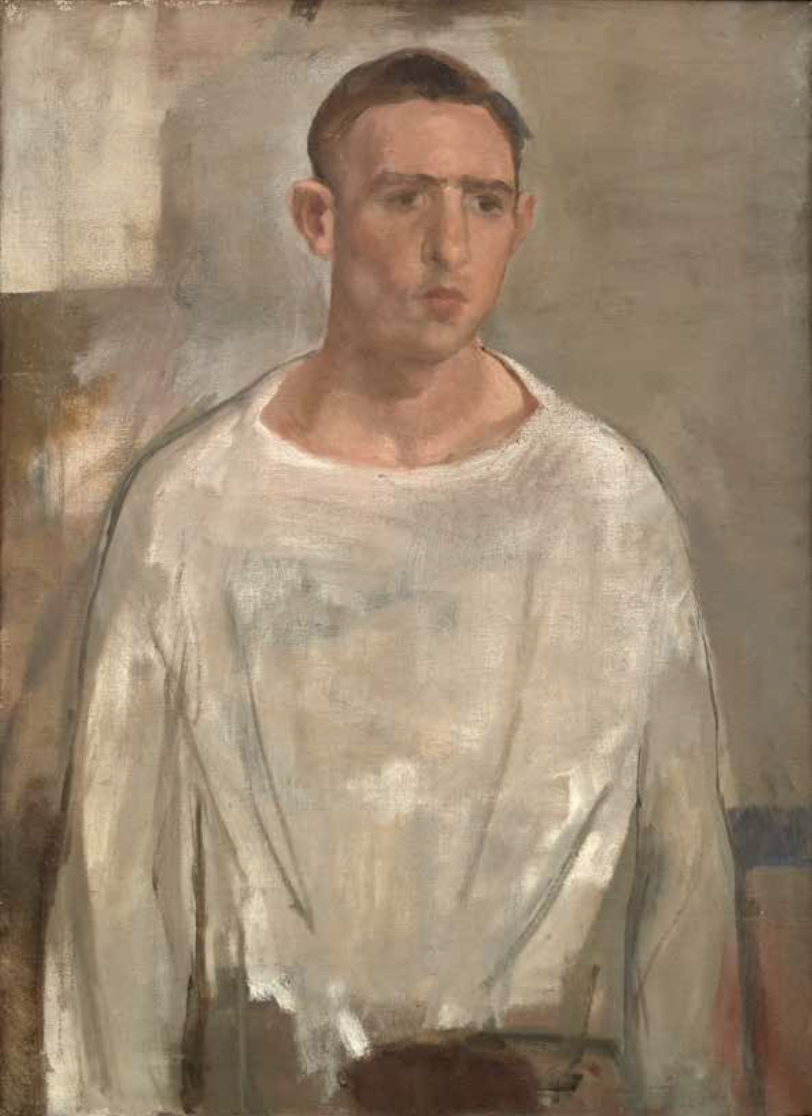

Portraits—“heads,” as Anderson called them—had always been particularly important to him. Back in 1951, he had begun painting portraits of his fellow students in graduate school at the Cranbrook Academy for $15 apiece, and he visited New York for the first time on the money he’d earned ($150) from them. But what was most important to Anderson about these portraits wasn’t the money. It was, rather, that in painting them he found a “kernel of something” he could work with as an artist. As he put it in an interview I did with him in 2013:

When I went to Cranbrook and I first started painting, I painted a portrait. I looked at it and I said, you know, there was something that I had never seen before in my work, and it came from the model. So I glommed onto that, and had something there, some kernel that I wanted to work with.

As he matured in his art, portraits remained a personal pleasure and fascination for him, even when they seldom sold. They were the gold standard of painting—“heads showed an artist’s mettle,” was the way he put it. And so, along with still lifes and bacchanals, he painted portraits in his Park Slope studio, most often of friends and family.

Guided by a gallery of “heads” that artists before him had painted all the way back to Fayum mummy portraits, he painted his first wife, Mimi, fellow artists, the light on his daughter’s face when she was still a child and would submit to posing for her father (imagine: prolonged stillness at eight). He painted his second wife, Barbara, many times, capturing the play of time on her face and body. Painted Morris Dorsky, the chairman of his department at Brooklyn College, finding it “kind of wonderful to see how Morris’s aging forms were working together.” He finished his portrait of A. Bartlett Giamatti in his studio, too, retreating to that third-floor refuge after struggling for weeks to paint Giamatti in his office at Yale while he watched football on television.

“Ask it what it is, don’t tell it”

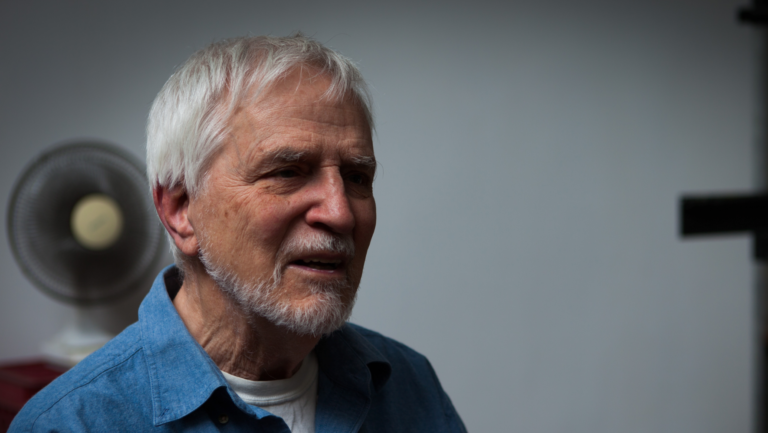

Many of the portraits Anderson painted from life are now on view at the Studio School’s retrospective, alongside the portraits—drawn in part from imagination—in his street scenes and bacchanals. As in Velázquez’s depiction of Juan de Pareja (one of the historical portraits he loved), there is something inviolable in the aspects of his sitters. No one is a slave, and even a child has a well of selfhood that draws our gaze.

Generally, Anderson said little when it came to painting. The few things he did say suggest that inquiry, uncertainty, and doubt were central to his thinking about art. He said, for instance, that his paintings should not raise any unanswered questions. But at the same time, according to his friend Paul Resika, Anderson liked the following statement by Yeats: “Only that which does not teach, which does not cry out, which does not persuade, which does not condescend, which does not explain is irresistible.” This implies the expectation, it seems to me, of a question being raised of the thing under consideration. And, as I know from spending time with him near the end of his life, Anderson often said, “Ask it what it is, don’t tell it.”

Inquiry over certitude

Anderson’s generative doubt, his incredible openness, is embodied in his paintings and calls forth a similar questioning gaze from me. It’s one of the things I think is so special about his work: it helps us see the world anew. That’s not only because his paintings allow us to see what Anderson did with his extraordinary rigor and insight. It’s also because his paintings allow us to see a little like Anderson did, with wonder, curiosity, uncertainty.

When I look at his portraits (and many of his other paintings as well), I have only questions, no answers. Who is that person? I might wonder, as when I look across the room and someone catches my attention. Is that child listening to the muffled street noise that penetrates the studio and wishing she could go out to skip along the sidewalk up to Prospect Park? Is she thinking about her father, or does she hear something that others don’t know to listen for—a flute being practiced in the brownstone next door, a cat scratching to get in? Is she yet at the age where her secrets have more to do with wishes and wants than small transgressions?

And Barbara, what of her? What has she left behind? Was there ever a time when she disliked the features that make her a distinct and beautiful woman? Has it taken effort, even sacrifice, to remain so self-possessed? Has she heard some news that has made her unhappy?

What we notice reveals our love. When I mark the intentionality of the brushstrokes on Anderson’s canvases—so finely nuanced that they express the empathy behind seeing a thing tenderly, as if it has been touched—I find myself feeling that we could change the world if we looked at it the way Lennart Anderson did. He affirms that the notion of art saving us is, after all, not a platitude, that we can choose empathy over apathy, connection over rupture, interest over indifference, inquiry over certitude. It seems to me that this may be one of the things that—to borrow from Martica Sawin’s introductory essay in the catalog that accompanies this show—lifts Anderson’s work “beyond the matter-of-fact and delivers it to posterity.”

The Vision and Art Project is an educational initiative of the American Macular Degeneration Foundation (AMDF). As a continuation of its commitment to supporting the lives and legacies of artists who experience vision loss due to macular degeneration, AMDF is also one of this exhibition’s major sponsors. You can find out more about their extensive research and educational initiatives here.

Further Reading

Lennart Anderson

“Seeing with Light:” A Film Profile of Lennart Anderson

In this short video profile, Lennart Anderson talks about his life. He also works on a portrait of fellow artist Kyle Staver.

Read More

Leave a Comment