Georgia O’Keeffe in Paris

December 01, 2021

As this stunning retrospective shows, Georgia O’Keeffe’s subjects were transfigured by the artist’s unique insights into nature and sensitivity to the sentient life of things.

An American legend not widely shown in Europe

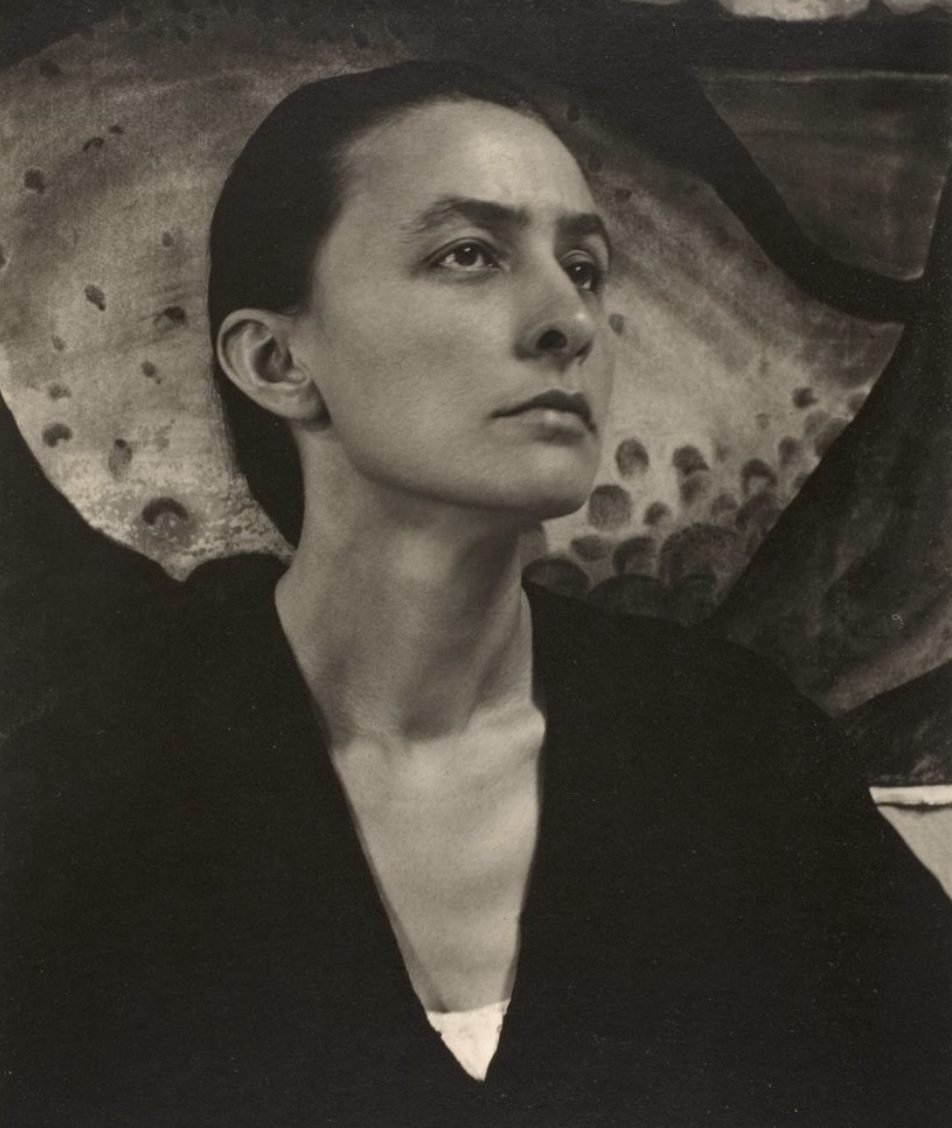

Though born almost a century and a half ago, no artist has yet to replace Georgia O’Keeffe as America’s foremost woman painter. Recognized by critics, collectors, and museums during her lifetime, her work was the subject of the first retrospective MoMA devoted to a woman artist (in 1946) and in 1987 at the centennial of her birth, the National Gallery of Art launched a major exhibition. By that point, she had long been a sensation, recognized as much for her personality and the image she cultivated (captured by the most important photographers of her time) as for her dramatic paintings of blown-up flowers and animal skulls.

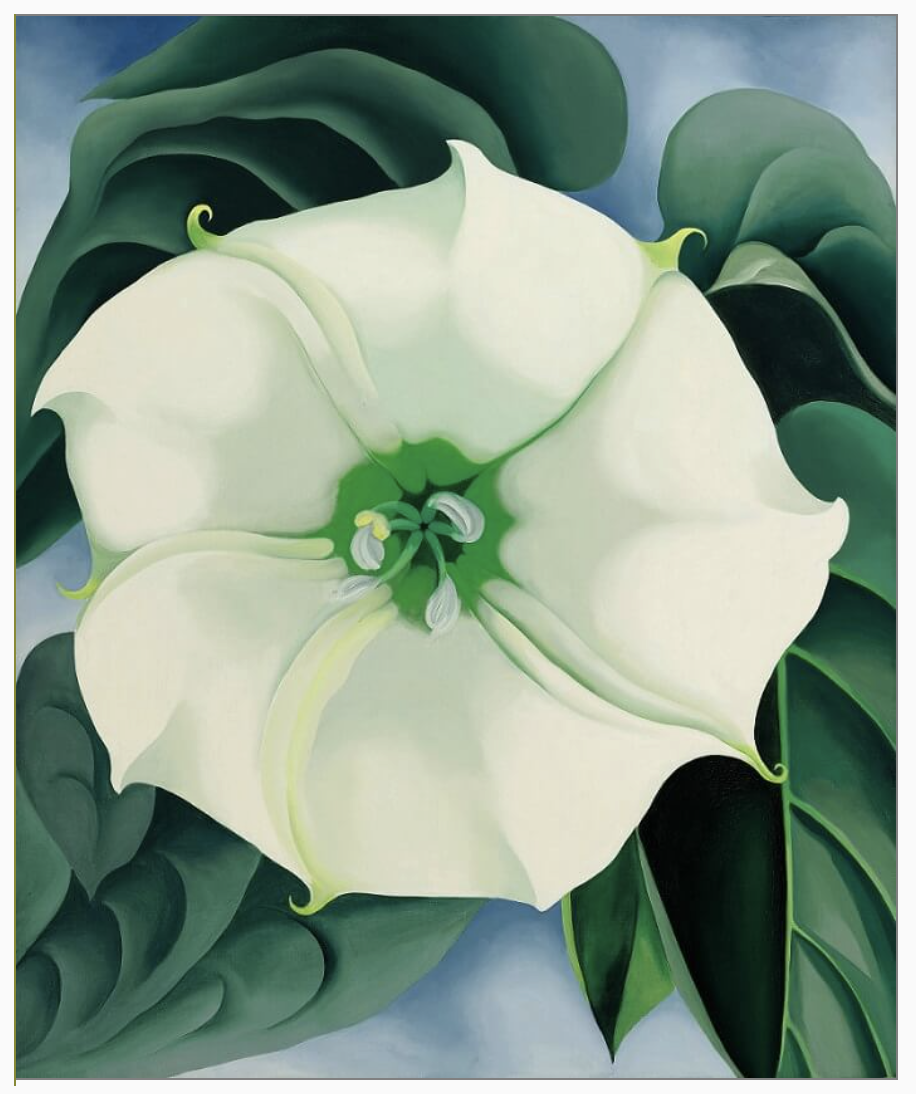

Since her death in 1986, O’Keeffe’s stature has only grown. In 2016, her painting Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 (1932) sold for $44.4 million at Sotheby’s, the highest price ever fetched for a work by a woman artist. Yet Georgia O’Keeffe, an American legend, has had few major shows in Europe. Except for the Tate’s 2016 retrospective of her work, there had in fact never been a major O’Keeffe retrospective on the other side of the Atlantic until the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid launched its exhibit last spring.

This retrospective is on view at the Centre Pompidou in Paris until December 6, 2021, after which it travels to the Fondation Beyeler in Basel (January 28–May 22, 2022). The show includes 108 works by the artist spanning more than six decades. It also includes work by many of her near contemporaries, which helps to define the modernist zeitgeist in which O’Keeffe emerged as an artist and contextualize her work’s influences and inspirations. The exhibition draws clear and convincing connections between O’Keeffe and the artwork of her time, early American landscape painting, and the transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman.

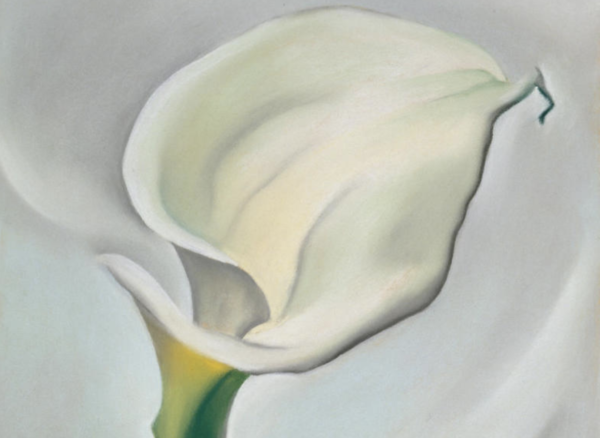

To be sure, the first and greatest gift of this exhibition in bringing so many of her original works together into one space is to showcase O’Keeffe’s mastery of painting as a physical act: the laying on of paint, the shaping of it, the feathering of edges, the intentional and insightful placement of brushstrokes, the choreography of surface textures across a canvas.

Nowhere is this more clear than in Series | White and Blue Flower Shapes. Close examination of this piece reveals the deeply-seeded classical training she received from instructors such as William Merritt Chase, who she studied with at the Art Students League of New York, evident as she lays paint in from thin to thick impasto to bring her subject out of the shadows and into the light, her bristle brushes leaving tracks and tracings of her mind. Reproductions of her work are so ubiquitous, it is easy to see and understand O’Keeffe’s images strictly as graphic compositions, almost as if she were merely a graphic designer. To experience them in person at an exhibit of this scope, though, is to become aware of the deep physicality and mastery of her craft.

With this said, as the complexity of her work began to reveal itself to me, I was most struck by O’Keeffe’s singularly unique vision, one not so much quintessentially American in orientation as planetary in perspective. In her work, the assertion of a cosmological realm outside our everyday human lives prevails. Her twenty-first century relevance may be that, except for herself as a feeling artist, her work is devoid of human presence and asserts as an enduring force the primacy of nature. It is a radical vision in the Anthropocene.

“Studio 291” and “Early Works”

With the goal of showing the ferment of modernism in which O’Keeffe launched her career as a painter, the exhibition, which is arranged in part chronologically and in part thematically, opens with a space devoted to Studio 291, the gallery that photographer Alfred Stieglitz founded in 1905. Here O’Keeffe encountered modernist artists from Europe who inspired her—Paul Cézanne and Auguste Rodin among them—as well as American painters who would prove formative in the development of her own vision—Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley.

All were formally inventive artists who eschewed literal depictions of the world; several of them, like Dove (who would prove deeply influential for O’Keeffe) were explicitly concerned with a more mystical understanding of the world and the vital spirits that animate it. Georgia O’Keeffe’s works sit next to that of some of these artists to show how, far from being a solitary genius whose work sprung from some isolated source within, O’Keeffe developed in active relationship with the artists and ideas of her time. Of special note to me was a pairing of a watercolor nude of O’Keeffe’s next to a nude drawing of Rodin’s, in part because it was the only reference to a human form by O’Keeffe in the retrospective, and, indeed, aside from a few portrait drawings later in life, O’Keeffe’s work was never concerned with the human form—or animal life, for that matter.

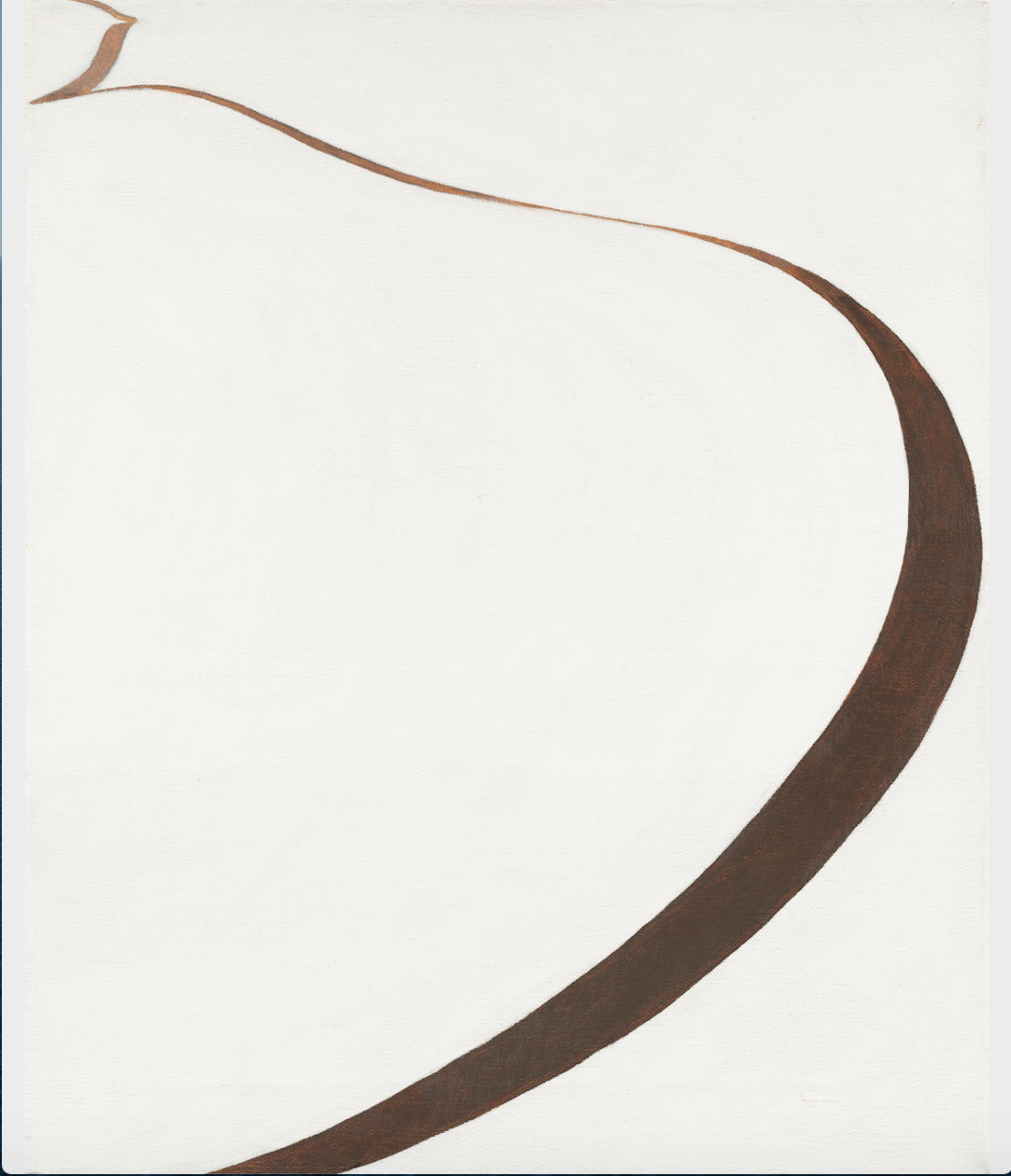

It wasn’t just that O’Keeffe discovered influences and ideas at Studio 291, though. Stieglitz and his gallery became the hub of O’Keeffe’s personal and professional life for many years to come, as she found in Steiglitz a romantic as well as artistic partner. In 1918, he championed and showed a series of O’Keefe’s abstract charcoal drawings that would form the foundational language for all her subsequent work. The language that she developed in these drawings (1915–18) allowed her to express, as she put it, the “things in my head, the shapes and ideas so near to me—so natural to my way of being and thinking.”

Stieglitz would continue to manage her career in the decades that followed. Upon divorcing his first wife, he and O’Keeffe married in 1924, after having lived together for several years beforehand in New York. Though he died at what would become the mid-point of O’Keeffe’s career, the exhibit suggests that Stieglitz continued to influence O’Keeffe throughout the remainder of her life. Several of Stieglitz’s cloud photos are presented in the Studio 291 section, and are invoked again at the end of the exhibition when one of O’Keeffe’s last oil paintings, Sky Above Clouds/Yellow Horizon and Clouds (1976/77), is seen as still drawing from them.

“Towards Abstraction”

Like Vasily Kandinsky, whose Concerning the Spiritual in Art she had read in 1912, O’Keeffe aligned herself with a path in art that was concerned with feeling and empathy for the sentient life of things. Yet, though influenced by artists like Kandinsky and Dove, O’Keeffe developed her own unique formal language, taking the waves, radiations, meanders, pools, and spirals that animate the natural world and refining and evolving a unique perceptual system that guided and structured her paintings for the rest of her career. Although the exhibit does not expressly explore this alphabet of forms, it shows how O’Keeffe moved from her abstract black-and-white charcoal drawings to abstract watercolor and oil paintings that combine the unique forms she had discovered in the drawings to create highly active, vibrant visual surfaces.

While many of her abstractions have no objective reference, there’s little distance between her seemingly non-objective abstractions to a painting like Inside Red Canna (1919), one of her first blown-up flower forms, a subject she would turn to frequently until the 1960s, when her work underwent a dramatic change and such detailed treatments of organic forms, including flowers, began to disappear.

“From New York to Lake George“

The decade from 1920–1929 saw Georgia O’Keeffe, then partnered with Stieglitz, living between New York City and Lake George. The subject of her paintings in those years included landscapes, cityscapes, plant life, still lifes, and abstractions, but rather than a purely chronological presentation of her work, the exhibition devotes a section to O’Keeffe’s paintings of New York City and Lake George (including the local barns), reserving her paintings of organic forms from this time for a section called “Plant World.”

It’s in these paintings of Lake George and New York City that the absence of the human as an integral component of O’Keeffe’s vision becomes apparent. And, by extension, how inconsequential the human world is within the cosmology of time and history that concerns O’Keeffe.

O’Keeffe’s skyscrapers, like The Shelton with Sunspots, N.Y. (1926) evoke an air, like Pompeii, of a vanished civilization. Looking at them, it’s easy to feel that what’s been documented is that which will remain of a city, any city, when its inhabitants have inevitably vanished. Devoid of people, buildings are eaten by the sun. What pulses with life—and will endure because it is endlessly replenished by the regenerative forces of nature—is beyond the Shelton: the squiggling, radiant clouds and orbs of sunspots dropping from sight.

As for the barns, O’Keeffe, who had grown up on a farm in Wisconsin, was painting them through the lens of memory, which is perhaps part of what imbues them with a sense of loss. Like New York’s skyscrapers, though, they are also strikingly devoid of people, which O’Keeffe subtly emphasizes by including signs of someone having once been present. Doors open, for instance, sometimes to implacably black interiors and sometimes to the shadowy shape of some indiscernible furnishing within.

The buildings are dead and the city empty, but the natural world and its elements teem with energy, movement, and life, pointing toward some greater immensity beyond them. Such paintings seem to foretell O’Keeffe’s own movement toward the stark, vast New Mexican dessert, where she began to live part time in 1929 before moving there permanently in 1948.

“Plant World” and “Bones and Shells”

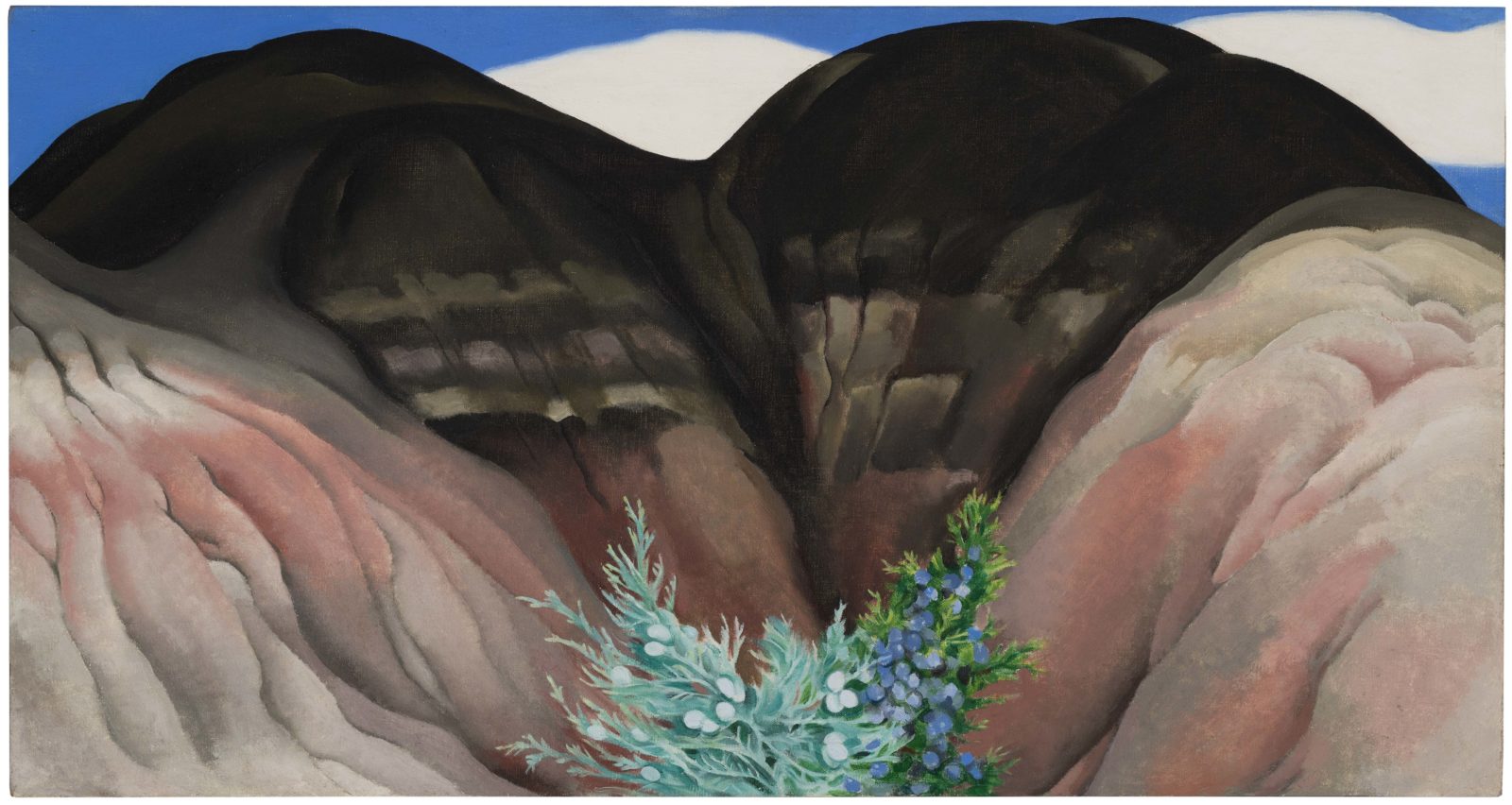

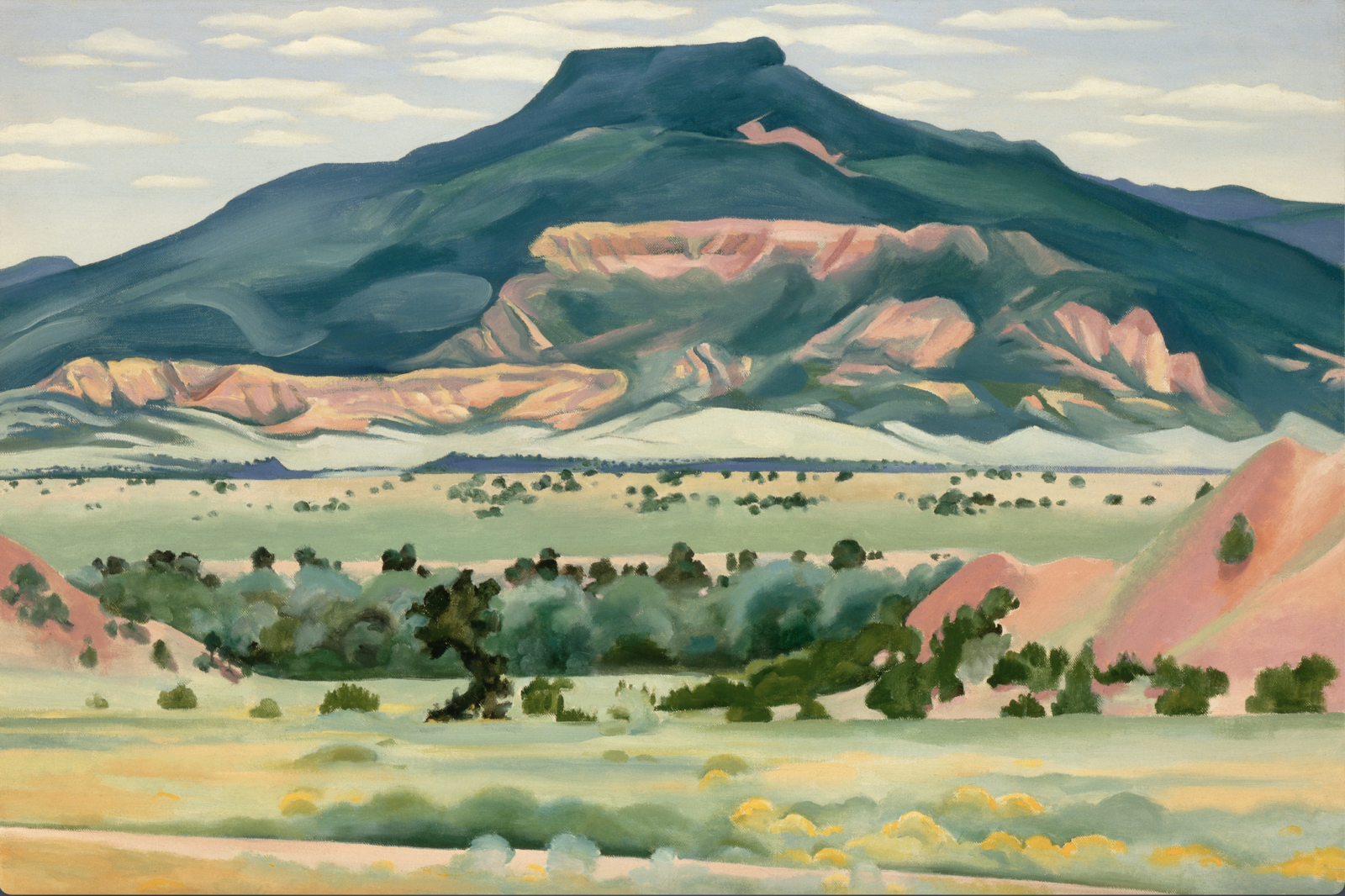

As this exhibition makes particularly evident, O’Keeffe did not progress through her work in steady, clear-cut stages, but rather all at once. As soon as she developed the language that allowed her to express what she perceived and felt about the world, she also discovered her subject matter: the cycles and movements of life as embodied in nature. She painted energy—and the pathways it takes. Trees branch, flowers blossom, leaves press upward and outward, skunk cabbage spirals, sun and stars radiate. While upon her discovery of New Mexico in 1929, O’Keeffe’s subject matter broadened to include such things as the particularity of the New Mexican mountains and bleached bones, until the 1960s, she continually returned to the same subjects and motifs without ever seeming to exhaust them or repeat herself, perhaps in part because she was documenting life force itself, never a static thing.

While her paintings of New York evoke a cosmos that persists outside human existence, her paintings of plant life and of bones and shells (which are treated in a different section of the exhibit), turn inward to describe a cosmology that is at once visible and tangible. In these works, she captures the outer shape and appearance of things in carefully articulated brushstrokes of clean, vibrant paint. She is ever attentive to eccentricities inseparable from the distinct personality of each subject, such as in her painting of a dead cottonwood tree, in which she brings precise and empathetic observation to its splitting bark. These paintings come to life and can appear to move. And most strikingly, as I stood facing a long phalanx of her oversized flowers (masterpieces all), light seemed to glow from within.

They put me in mind of a quote by William Blake from his Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793): “If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite.”

“New Mexico”

Part of the magic of O’Keeffe is that while her transcendental vision emphasizes nature and eliminates the human, at the same time she imprints upon her work the utmost personal traces and tracks of herself, her hand and eye, moments and exceptions that intrigue and confound. The grandeur of her close-up flowers and plants are dependent on the lens through which they’ve been seen, which is decidedly, willfully, O’Keeffe’s.

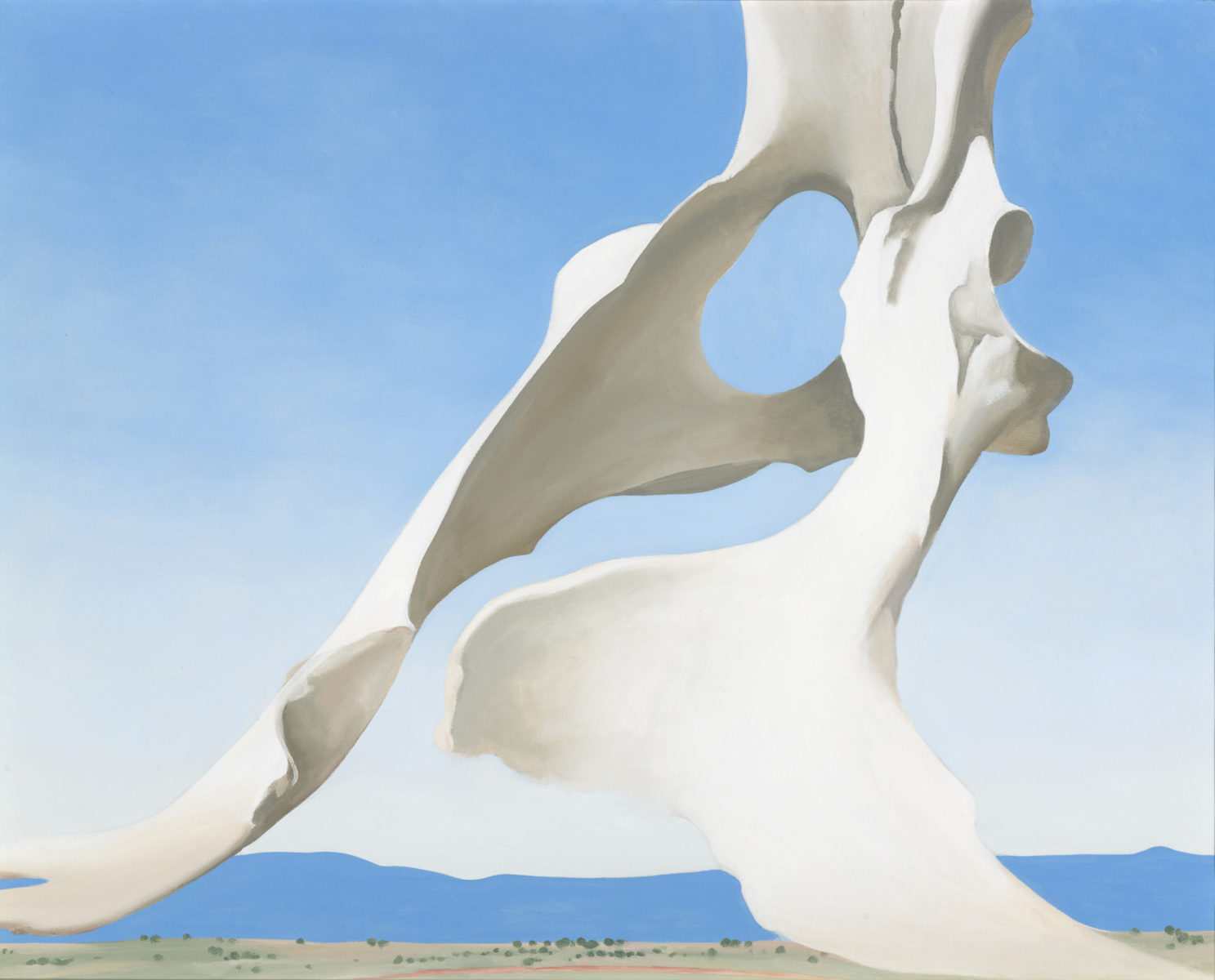

An entire section of the exhibit is given over to “New Mexico,” and it is here that O’Keeffe’s paintings from her Pelvis series (the first of which she painted in 1943) and her Ram’s Head, Whit Hollyhock-Hills (1935) belonged, I felt, as opposed to in a section of the exhibit featuring her bones and shells. Not because they are set against the Southwestern landscape. But because, like O’Keeffe’s images of churches, crucifixes, and kachina dolls, they show O’Keeffe using her language to try to tell us a story.

While O’Keeffe was always prominent as the perceiving and feeling creature in her other works, in her motifs from New Mexico, she often seems to be trying to express a mythology. While her flowers and leaves can be seen as exercises in pure observation—albeit through O’Keeffe’s distinct lens—it is an act of imagination to paint a pelvis looming like a monumental sculpture against the horizon, a hollyhock and the skull of a ram suspended like a vast vision against a stormy sky, or a gray cross dominating an impossibly blue background.

One of the many O’Keeffe quotes in the wall text at the exhibit refers to the blue in her Pelvis paintings as being “that Blue that will always be there as it is now after all man’s destruction is finished.” It was not only in those paintings that she was thinking about man and destruction but also in her Black Place paintings from 1944, which seem to be a direct reference to the Armageddon of World War II.

“Cosmos”

As the exhibit acknowledges, O’Keeffe’s work from the 1950s and 1960s changed dramatically. She painted a series of her Abiquiú house patio door using minimal shapes and lines, created overtly symbolic paintings such as Ladder to the Moon (1958), paintings that explicitly referenced memory, paintings from an elevated view of meandering riverbeds and roads. Along with the change in motifs, her style and techniques became different, as well—colors in some cases brighter, in some cases more washed out; forms vastly simplified; canvases larger. These paintings are presented as developing out of O’Keeffe’s earliest impulses as an artist—to align herself with Kandinsky and the spiritual in art. Except that while her earlier works explored the vital spirit and sentience of things, in these works she was attempting to “render the spiritual and mystical feelings” the subjects inspired in her.

Strikingly, this show suggests that the work she did in the 1950s and 1960s was—with the exception of her 1970 painting Untitled (City Night), her 1976/77 painting Sky Above Clouds/Yellow Horizon and Clouds and a clay pot from 1980—the concluding phase of her career. It notes that O’Keeffe lost central vision in 1972 due to macular degeneration, and that upon meeting Juan Hamilton in 1974, she began making pots because it had become difficult for her to paint (Sky Above Clouds, for instance, was painted with assistance). In fact, the story of her macular degeneration is more complex and uncertain, and the work she did after going blind is the true final stage of her career.

We don’t really know when O’Keeffe began losing her vision

The chronology posted at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum indicates that O’Keeffe lost central vision in 1971. But it’s hard to know when her vision loss actually began—and, by extension, at what point her paintings may have begun to be influenced by the disease. In part, this is because macular degeneration often exerts a subtle, nearly imperceptible pressure on vision (such as making it harder to discern contrast) long before it interferes with visual acuity in more obvious and profound ways. In Georgia O’Keeffe’s case, this natural ambiguity regarding the disease’s onset was complicated by her secretiveness about her eyesight. A secretiveness that held to the end of her life.

One biographer, Roxana Robinson, says O’Keeffe started to lose her sight around 1971, when she was 84 years old. As recounted in Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life, O’Keeffe was returning from town when she noticed that the day appeared unusually gray, given that the sun was shining. After experiencing several more days of dull, blurred sight, she sought help from eye specialists. Her visual acuity was found to be 20/200. Her vision loss, she was told, was irreversible and incurable. Robinson also relates that, when O’Keeffe’s close friend Maria Chabot made her look out at the Pedernal (the narrow mesa near Ghost Ranch that O’Keeffe had often painted) from her terrace in 1971 and asked if she could see it, O’Keeffe said no. Which suggests that by 1971, O’Keeffe’s vision loss was very severe.

O’Keeffe’s friend, Nancy Hopkins Reily, tells a different story. In her book, A Private Friendship, Reily says O’Keeffe began experiencing trouble with her eyesight in 1968.

Yet an earlier date is put forth by Jeffrey Hogrefe. In O’Keeffe: The Life of an American Legend, he maintains that O’Keeffe first noticed signs that something was amiss with her vision in 1964. She immediately visited an eye doctor and learned she had macular degeneration.

In a manuscript from the 1970s that O’Keeffe wrote called “My Eyes and Painting,” she herself gives us some clues as to when she lost vision when she says that she was about 80 (which would have been 1967).

“My vision had always been very sharp — both near and far. When my eyesight was particularly good, I could read very fine print and count the trees on the mountains miles away. When my eyes began to not see sharply as they had for 80 years and the world began to turn grey, I was bothered and gradually stopped working. In time, I was surprised that this world could sometimes be beautiful in a new way, and began to think — how could I start again and begin to paint this new world. Juan helped me — he was sometimes very unpleasant by pushing — urging me to try.”

Georgia O’Keeffe, 1970s

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Post Macular Work: Weight, Memory

Many people who knew O’Keeffe in her last years describe how she would hold the stones she collected in her palm, seeming to gain pleasure from their cool weight. Her Black Rock paintings (not included in the Pompidou retrospective) might be seen as deriving from just such a tactile experience, not rocks but polished sculptural boulders hewn from paint, dominating horizon and canvas with the weight, immobility, and inviolability of stone. Other painters have concerned themselves with gravity and weight—Titian with the rock his version of Sisyphus strained against—but no painter before O’Keeffe had made so pure a memorial to the implacability and universal resonance of stone.

Along with representing and evoking tactile experience in her post-macular paintings, she also made paintings based on memory that evoke the act of remembering. A painting like Sky Beyond Clouds/Yellow Horizon and Clouds returns to and echoes works she completed much earlier in her career, such as her paintings of Lake George from the 1920s, though Sky Beyond Clouds, like a memento mori, is writ in what is perhaps her most transcendent air, as if she had at long last distilled the essence of emotion she was trying to capture in her many paintings of distant horizons.

A similar feeling pervades her last abstract watercolors (also not included in the retrospective), which, as Hunter Drohojowska-Philp has said, “are poignant in their similarity to her early watercolor exercises of 1915, as if she were reaching back to that moment when her life and her art emerged as fully formed.”

It’s a missed opportunity not to look more closely at this stage of her career, in which O’Keeffe ultimately circles back to the language that she had developed nearly seven decades earlier and that had given her the power to express so much.

A French-language catalog accompanies the Pompidou show. A slightly-different English-language version, which was published by the the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, is also available. You can find our review of it here.

Further Reading

Comments

To whom it may concern….as a member of this group I reposted this link. I got restricted on FB because this material was considered sexually explicit….

I do believe they are wrong.

Very sorry to hear this! Thank you for letting us know, and thank you for reposting. We’ll look into why this happened to try to ensure that it does not happen again.

Thank you for such an in-depth exploration of a life well lived. Georgia O Keeffe is very inspirational

Thank you for your comment! Yes, her work is amazing.

Leave a Comment