Breaking Radically with Indifference

May 30, 2022

With graphic images of the war in Ukraine so prominent in the media, and our world suffused with violence, I am reminded of Doris Salcedo’s artwork and her moving and profound response to political violence.

As an alternative to the disturbing content in the media, Salcedo’s sculptures offer another way of being engaged in the world and its troubles, one that calls forth a more genuine and lasting empathetic response to the suffering of others. I first encountered her work at an exhibition at the Fogg Museum in 2017 (at which time we interviewed her at the Vision & Art Project about her vision loss). Among the pieces on display was the Disremembered series, an assemblage of ethereal cloaks woven from silk thread and steel straight pins, which memorializes the pain of African-American mothers who have lost their sons to gun violence in Chicago. Since having seen those works, I think of them every time I read in the news of a child perishing from gun violence. Simultaneously ethereal and tortuous, they evoke both unfathomable loss and unfathomable pain.

In a 2021 interview with Ben Luke for “A Brush with…podcast,” Salcedo discussed her belief that explicit representations of violence reenact that violence. She also talked about several specific projects she has undertaken during her career and explained how the works by artists such as Goya, who concerned himself with representing the victims of war, have influenced her.

Addressing violence without re-presenting and re-enacting it

As Salcedo explains, the main concern of her work has been to address violence without re-presenting and re-enacting it:

“It is very difficult to present images of violence, because these images are the worst profanation, are obscene, and I don’t think obscenity can be symbolized. It is what it is, and it cannot be transformed. So, my goal when working is to create images that address violence, but without presenting violence. Violence cannot be re-presented because then you will be repeating violence. If you present a body that has been assassinated or something horrible happened to it, if you copy that image, then you are re-presenting, re-enacting violence in that image. So for that reason I always try to avoid that.”

Early works in response to Colombia’s long civil conflict

From her earliest work, Salcedo sought out the personal testimony from victims of violence and those whose loved ones were disappeared. Initially, her works were a response to Colombia’s long civil conflict, which flared intermittently between 1948 and 2016, and in which over 220,000 people (mainly civilians) lost their lives. Millions more were displaced. In a group of early untitled works, she encased stacks of white shirts in plaster and pierced them with steel rebar. These sculptures were about the massacres of male workers at two banana plantations in Northwestern Colombia in 1988, but since Salcedo wanted the sculptures to be read as metaphors rather than representations, the steel rebar doesn’t pierce the shirts at the point where the heart would be.

The Unland series

Her Unland series from 1993, titled after a poem by the Romanian-born German poet Paul Celan, is based on the testimony of children whose parents had been murdered. The series consists of three works that initially just look like old, battered tables. In fact, each piece is made up of two tables which have been joined, a metaphor for the emotional rupture caused by the victim’s experience. Salcedo drilled tiny holes in the wood through which is sewn hair and thread, thus forging an association between the tables and fragile human bodies. She recalls in her conversation with Luke the painful nature of the interviews she did with children that inspired the work:

“I was interviewing a girl who was always wearing the same dress. She had witnessed the killing of her mother and when I went to the orphanage, she was wearing the same dress, and the dress was obviously too small for her. And one morning I was taking an early flight so I went to the orphanage like at 5 a.m. to leave a little doll for her. And she was already up and washing the dress because she had to wear it every day. Then she told me that her mother had made that dress for her. And that was the only thing she had.”

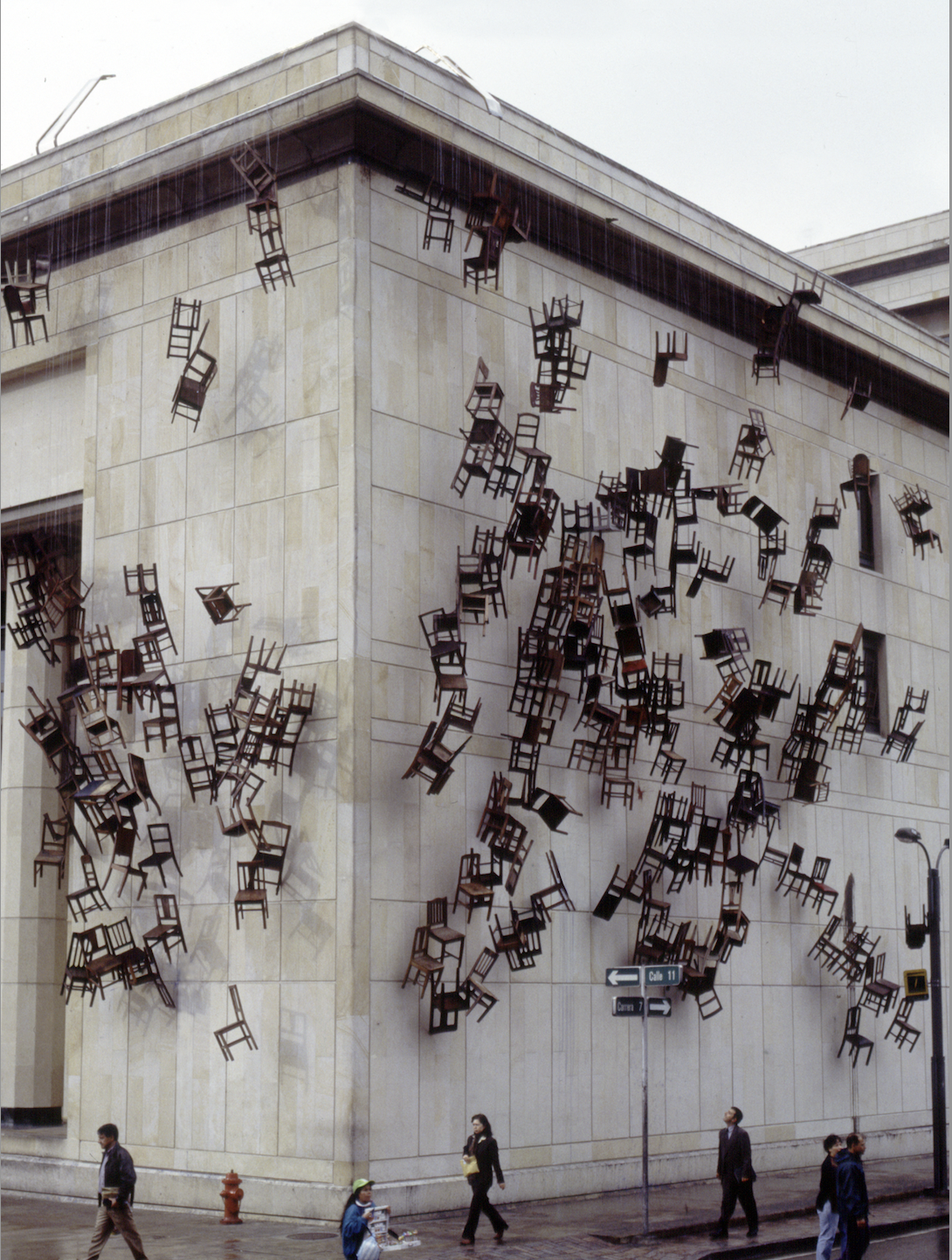

November Sixth and Seventh

Borrowing a term from art historian Mechtild Widrich, Salcedo has also made performative monuments. Her first one was November Sixth and Seventh (2002). In this work, 280 wooden chairs were lowered from the roof of the Palace of Justice in Bogotá over the course of 52 hours to commemorate the 17th anniversary of a violent siege of the Palace, which itself took place over the course of 52 hours.

“Shibboleth” and “Palimpsest”: the tragic dimensions of forced migration and displacement

Many of Salcedo’s recent pieces are about the tragic dimensions of forced displacement and migration. Her installation project Shibboleth, a fissure that ran the length of the concrete floor of the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, is about the violence of separation, borders, and gaps that infuse the contemporary world: between races, between rich and poor, between the global North and global South, between ourselves and the traumas of others, which we can often too easily forget.

Another of her works relating to migration was Palimpsest, first exhibited in 2017 in Madrid’s Palacio de Cristal. Textured slabs of stone lined a room, on which were displayed the names of more than 300 refugees who died in the Mediterranean or Aegean while attempting to escape conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa. As if the stones are weeping, the names of the lost are shaped by water, which wells up through tiny holes in the stone, one name appearing, then disappearing, as another starts to emerge.

In order to create Palimpsest, Salcedo sought out the names of the migrants who had lost their lives. In talking with Luke, she explained how hard it was to find these peoples’ names—and yet how essential to the piece that those who died be identified by name:

“When I was doing that research, there was Syrian press, and Turkish press was freer than it is nowadays. So, we were looking for these names in press that was not only European press, or American press, but had a very hard time because the European Union refused to give me a list of names they had. There were several NGOs that refused to give the names. And so I had this really difficult task of visiting cemeteries where little pieces of cardboard were stuck to a pile of dirt and then checking that with press from different parts of the world. Each name had to be found at least twice in order to be present in the work. So, no name is made up. They are all verified.”

The victim’s testimony, the perpetrator’s thinking

Salcedo says that her first step as an artist is to “break radically with indifference,” by going to places where there are victims of violence and collecting their testimony. She considers these witnesses to be “partners” in her work. She never records or takes notes when she’s with someone; rather, she works from her memory of the encounter and the “delicate” and “subtle” cues in their environment that hint of what they’ve endured as a human being caught in an historical event. Her dialogue with them does not end with these interviews but continues as she works: “They are my interlocutors,” she says, “and my work is being made for them. Specifically for them.”

Along with the testimony and memory of the victim, Salcedo attempts to access and include the thinking of the perpetrator into her work, which results in the marked austerity of her pieces. As she explains:

“The perpetrator has planned the attack. They have bought the arms. Somebody paid them to do that. There is always a rationality behind it and that rationality is cold. Extreme coldness. Extreme coldness when you’re going to kill somebody, or when you’re going to displace somebody, or when you are enslaving a person, or forcing them to work in unbearable conditions. There is rationality, either political or economical. And the rationality is spare, is direct.”

Salcedo says that when she makes a work, she tries to put her own center in the center of the victim, a non-rational process that has her working from the “heart” of another person.

“I select the materials that are available and the pain that that person suffers. Then I start working with the most delicate materials. Because if you think of yourself, you are delicate. You’re a delicate being. Everything might hurt you—cold, or even a sip of hot tea might burn you. So, you’re delicate with yourself. I wanted to bring that same level of vulnerability, of delicacy, of love and care into the work. So, that’s why I’m looking for this most fragile materials and these absurd ways to communicate this vulnerability.”

Making her works is labor intensive, which Salcedo acknowledges is an absurd action, yet this absurdity is an essential component of what she does:

“I need this absurdity. It’s what allows me to reach a level of beauty, because the lost lives I am referring to are lives that were beautiful, that were complete, that were wonderful at some point. So, I need to show that infinite aspect of those lives that have been destroyed so brutally and out of time.”

One of the ways Salcedo conveys the experience of the victim is by transforming the intimate objects of everyday life—clothing, shoes, domestic furniture—into poetically resonant vessels of loss. She explains why these commonplace materials can be used to evoke terrible losses.

“When I interview mourners, they all keep objects that remind them of the person that is missing. Especially when I interview families who have a member taken away, disappeared by force. They keep everything, absolutely everything, every shoe, every sock, and sometimes the table is set with the hope that that person will at some point reappear. I have met mothers who have not left their home for more than 20 years because maybe their son will return, so they have to be there. And they have to be living in the same place and they keep the same landline because maybe the person will call. It is extraordinary to see the meaning of these objects for these families. They carry the clarity and the beauty of the life that is lost.”

Local/global

Salcedo is excruciatingly aware that the suffering violence causes is universal. It doesn’t differ according to where one lives:

“If I’m making a piece of art that’s about a massacre that happened in Colombia, that massacre will not differ a whole lot from the massacres we saw this week in the States. So, the pain is similar. The motive might vary. And when you live in a country at war, like I do, displacement is the most important aspect of the violence that takes place here. And so, we have internal refugees. People’s experience could be at the Cox Bazar refugee camp in Bangladesh [the world’s largest refugee camp], or in the border with Mexico and the U.S., or displaced people in Colombia—they experience the same. The current condition of advanced capitalism is kicking people out of their land. There are land grabs. Countries from the global North are grabbing land from the global South, displacing people. So, the experience might vary a little, but at the end it is the same thing. The brutality that all these people are experiencing is similar.”

The art and literature music Salcedo loves: making art out of darkness

In terms of artists who have influenced her, Salcedo has two early loves, Francisco Goya and Paul Cézanne. She describes seeing Cézanne for the first time in person at the Louvre and being transfixed. His work is meaningful to her because the kind of containment, precision, and thinking in Cézanne’s work is essential to hers, as well. She saw Goya at the Prado, and it was an “extraordinary, transformative moment,” as she describes, since Goya transformed the way we look at war by empathetically depicting its victims. Salcedo’s November 6 and 7 is in fact a nod to Goya’s the Second and Third of May. As she explains:

“Goya’s present in all my work. I mean looking at horror, straight at the face of horror, is difficult, and I think Goya taught me how to do that and not to flinch when witnessing the horrors of war, the horrors of political violence… Goya [in the Second and Third of May] presents us simultaneously with the victim and the perpetrator. And if you remember the perpetrators are in a straight line, in a rational straight line, shooting the victim. And you can see the empathy Goya felt for that victim, for all the victims, but especially for the one who was in the center [of his painting]. So, he has an empathy for the victim and an implacable, critical view of the perpetrators. That’s what I found extraordinary.”

She also admires Joseph Beuys, whose work helped her to see “sculpture as something having the possibility of giving shape to a society.”

She keeps Bruegel’s Triumph of Death and Rembrandt’s Self Portrait with Two Circles pinned to her studio walls for inspiration:

“I adore The Triumph of Death for obvious reasons, I think—that violence is so primitive. It doesn’t matter whether it is exerted nowadays by advanced capitalism or in the Middle Ages, by whoever, it’s the same. It’s primal, it’s brutal. And in terms of the Rembrandt, I have him everywhere. On all my computers and the screen in the studio, because it’s such an honest presentation of an artist. It’s a real artist. And I don’t want to forget that we have to be absolutely honest with our work. So, I adore that painting… We can never forget that that’s what it takes to be an artist.”

Another transformative experience for Salcedo was with the work of Paul Celan:

“Encountering a poet who’s able to convey horror and beauty simultaneously, whose mind is so precise that if a comma is missing then the meaning would be lost. And being a survivor, and having the courage to go back to Germany during the post war was unthinkable for Jewish writers. Every image exploded to me in my mind. Every single line conveys an infinite number of images, of feelings, of thoughts that I was trying to convey in [the Unland pieces that refer back to Celan]. On a daily basis I was reading [Celan] before I started working and usually afterwards as well. I needed that kind of pain to keep me doing this absurd action—stitching through wood with hair is such an absurd gesture. I needed Celan to guide me to that and to show me that poetry is absurd, and, as he says in The Meridian, absurdity is what speaks of the sovereignty of the human being. That’s what really honors a human life. Our ability to do things that are beyond need.”

Other works of literature also find their way into her work. She was reading Toni Morrison’s Beloved when she made her Disremembered series (2014), the assemblage of ethereal cloaks memorializing the pain of African-American mothers who have lost their sons to gun violence. Her conception of the series was influenced by the appearance of the ghost and the image of the white dress in Morrison’s novel. And because Salcedo starts each of her pieces feeling, as she says, “knowing nothing,” “lost,” and “disoriented,” she turns to philosophy for guidance, including to the writings of Hannah Arendt and Jean-Luc Nancy.

What holds everything together for Salcedo—the newspapers she reads daily, victims’ testimony, her engagement with literature, philosophy, and art—is a daily practice of sketching, which is the most private part of her work (she has never shown her sketches):

“I always sketch, but I have very poor eyesight. Actually, I’m legally blind. So, the more I get into this, the more I need the sketches. Before, I used to work by myself, doing everything alone, and as I lose my eyesight, I need assistance. I need help. When I was young, the pieces came through the use of materials. And now they come through sketches. So, I think almost completely through the piece, in those sketches. That’s where I present to my assistants and then we start to work with materials. So, the process has changed.

What is art for?

In closing his interview with Salcedo, Luke asks, “What is art for?”

“I have a specific perspective. I am from the global South. Art is a way of allowing people to express what violence impels them to do. Violence is a way of silencing. Violence destroys language. So, when somebody has killed a person you love, you don’t express that with words, but you express it, you cry, you weep. There are other sounds that are not languages. For me art is a way of structuring language that can express the experience of those who have not been able to express themselves.”

You can find Ben Luke’s entire interview with Doris Salcedo here.

Leave a Comment