Shooting Blind: How a Blind Photographer Takes Pictures Like a Sighted Person

March 06, 2023

I am a blind photographer. As oxymorons go, that’s right up there with “genuine imitation leather.” Fear not, though. I am here to help. Understand that the vast majority—more than 80 percent—of people conforming to the definition of legal blindness in the United States have some vision. About 18 percent are totally blind. Just what the other 82 percent of blind people can see is a function of the tremendous diversity and complexity of diseases and life events that can affect one’s eyesight. This means that the word “disabled” is itself a one-word oxymoron. Disabled people can and do engage in almost every activity imaginable. If there are some activities that are not accessible, they only serve to emphasize the tremendous range of life’s possibilities that are arenas of excellence for the disabled.

No central vision

My own impairment is called Stargardt’s Macular Dystrophy, a relatively rare (my ophthalmologist tells me) mashup of the juvenile Stargardt’s disease and a particularly vicious adult dry macular degeneration. A journey that began more than 60 years ago, a journey that has made Chinese water torture seem diluvian, the end result is easily and accurately expressed in three words: no central vision. And two more: no treatment.

Over this same arc of life and time, I have also been a dedicated photographer. I was a member of the Junior Division of the National Press Photographers’ Association in my middle teens. I was offered a job at the New York Times in my early twenties. I worked vacations and summers as an assistant in a well-regarded studio during the time epitomized by Antonioni’s Blow-Up.

Eyesight vs. vision, looking vs. seeing

After school, I spent more than 30 years in the commercial and academic art worlds, settling ultimately on the roles of advisor and finally, curator. In the midst of the steady thrill this work provided, I began to lose my eyesight. I say “eyesight” rather than “vision” because there is a difference between “looking” (using one’s eyes to view the world) and “seeing” (using one’s brain to understand what has been sent to it by the eyes). Looking is the acquisition of information with the eyes; seeing is the thought process that brings to bear a set of intellectual tools comprised of inherited qualities and accumulated experience. We find guidance about this idea, at times bewilderingly complex, and at times self-evident, as long ago as in Plato’s Allegories of the Cave and the Sun from the 4th century BC and more recently in Temple Grandin’s work, including her 2022 Visual Thinking: The Hidden Gifts of People Who Think in Pictures, Patterns, and Abstractions.

By 2005, I was forced to stop working (and driving and cooking and shopping for clothing and and and). Nobody hires a blind art advisor or curator. After more than 60 years of visual education, the “front end” of the eye/brain partnership was taking its leave.

Visual memory

According to my amateur research, the brain’s work in the eye/brain joint venture is based on memory. It’s my own observation that my intensive, very long-term visual experience, much of it at a very demanding level, became my own in-brain Wikipedia, complete with links for further reference. I am, it seems, a visual thinker.

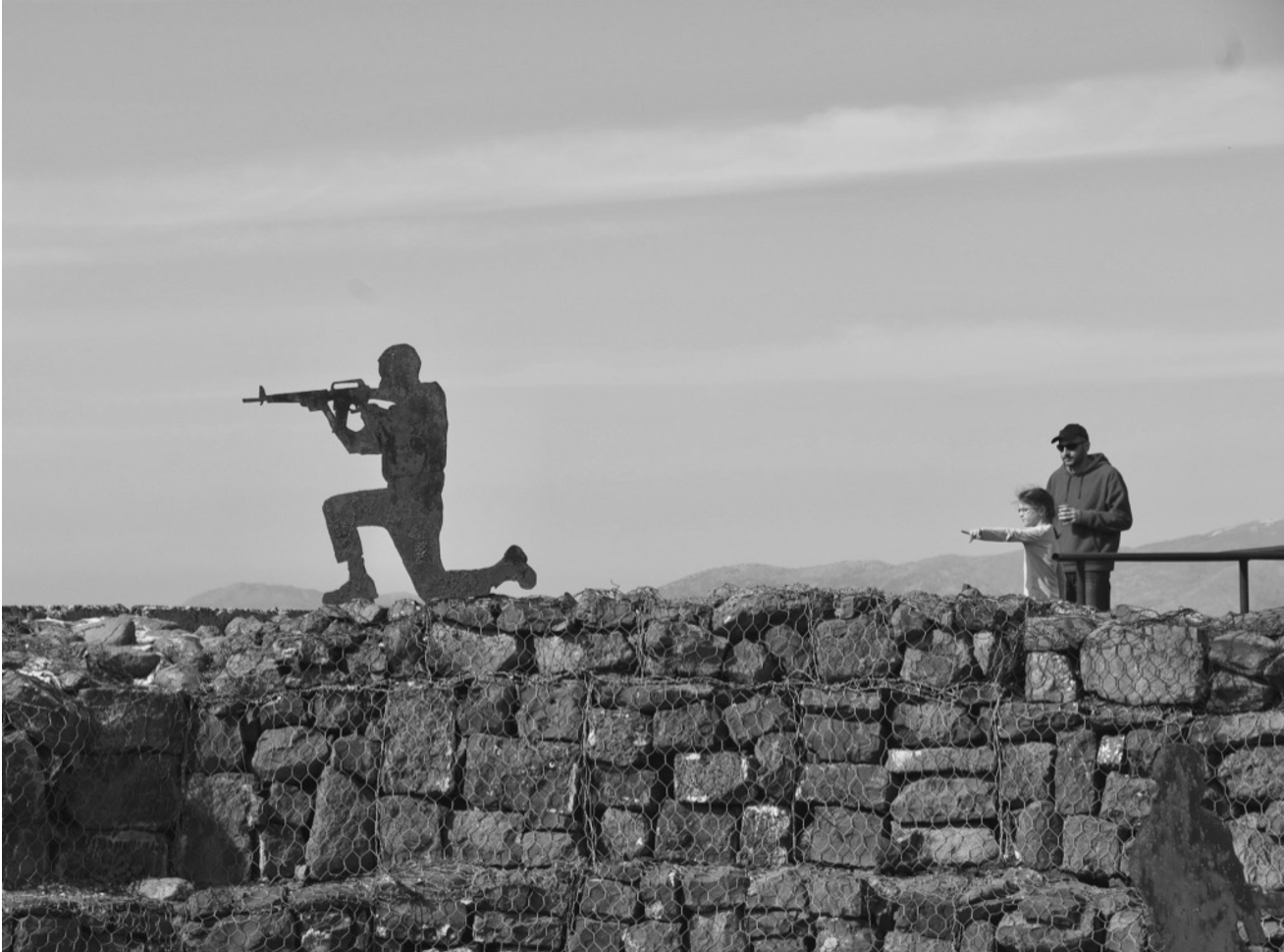

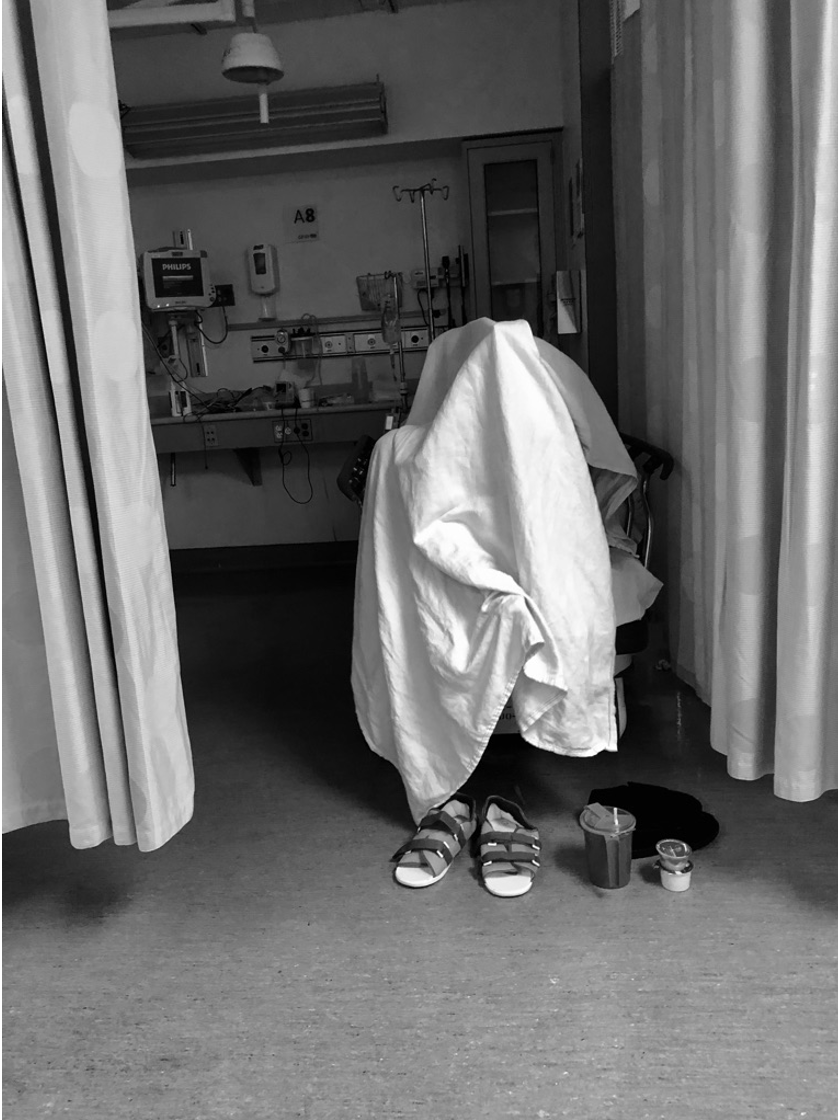

I still take pictures almost every day. Each time I press the shutter, I am recruiting not only my six decades of visual education, but also the unimaginably complex neural networks through which the image stream travels. In much less than the 1/125 of a second at which I usually shoot, every last bit of visual memory is queried about the likely result of pressing the shutter, even though I can’t see anything in the center of the frame.

Throughout this essay are some pictures I’ve taken since my central vision became irreversibly clouded with the lowering storm of merging atrophies. Just above is a contact sheet of the view from the elevator lobby on the 6th floor of the Jewish Guild for the Blind building, which formerly occupied the northwest corner of 65th Street and Central Park West in New York City, now demolished. It was on the 6th floor that I met with a talk therapist. At the end of each session, I took a snapshot of the same view while waiting for the elevator. The idea was to show the infinite variations in the light on the scene, sometimes dramatic, most often subtle. Here, the contact sheet is overlain with a schematic representing what my vision was like 10 years ago. This being a progressive disease, it’s worse now, but the picture-taking continues.

If you have found this interesting, I would be very glad to hear from you. I can be reached at robert.schonfeld@gmail.com. My Instagram page is: seeing_while_blind

This is an original work written and photographed by guest essayist Robert Schonfeld. ©Robert Schonfeld. All rights reserved. February, 2023

Comments

Reading your story with fascination.

My admiration goes to you where you don’t believe that any kind of handicap should keep you away from the work/hobby that you previously and now are so good at.

I would be happy to follow you on Instagram to remind me more and more that every day is a new opportunity to show the beauty of the world to the people who surround us.

Thank you for sharing your link on NYT comment.

As someone who shares low vision/blind recent history and now has wonderfully fairly restored day time vision in one eye, I am keenly aware of the fragility and temporary nature of vision. But also the gift of seeing differently.

During a time they were trying to restore vision in my now totally blind right eye, I had a Monet like view of the world and with no lens in my eye to screen out UV light I saw intense colors everywhere. Although I don’t have the rods and cones of creatures who fully comprehend the UV spectrum, I will never forget the memory of experiences like seeing blueberries on the bush with my left eye as blurry, but typical color, and turning my head to see the same blueberries with my right eye also blurry, but throbbing intense deep purple color. Is that how they appear to birds?! I repeatedly tested this experience in the everyday – from the first experience of the woman walking by in peach colored sweatshirt that turned intense coral, when viewed by my right eye. I still treasure the year in which they tried to rebuild the right eye (only to ultimately go totally blind in that eye) for the gift of seeing the world so differently.

Now in my largely restored left eye, my nights look like some version of the second coming. Beams of light from even the tiniest light everywhere make navigating the outside world difficult without assistance. There is nothing that can be done about it. But the streams of light are so beautiful, so rich. There is light everywhere that in all the previous decades of normal sight I’d never appreciated.

It is inspiring that you and Samantha Hurley used your different vision to bring something rich and illuminating to the world.

Leave a Comment