Faces Places and Agnès Varda’s Radical Generosity

October 15, 2022

It’s been five years since Faces Places was released to general acclaim. One of the things that made the movie great was Varda’s radical generosity in sharing that she was losing her sight to macular degeneration.

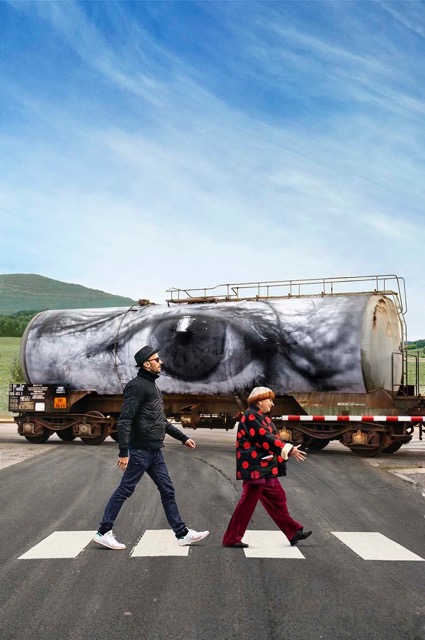

Agnès Varda and JR make a film

About five years before Agnès Varda passed away, her daughter, Rosalie Varda, introduced her to the photographer and visual artist known as JR. Somewhat improbably, perhaps, Agnès and JR talked about collaborating on a project. Somewhat improbably because JR was the hip, young mastermind behind such instantly iconic images as the gigantic photograph of a child peeking over the U.S. border wall with Mexico, while Agnès was the elderly doyenne of the French New Wave, no less hip but of a different time.

Despite being generations apart, however, Agnès and JR’s artistic preoccupations overlapped. Like JR, Agnès was passionate about photography. Early in her career, it was the first art she’d practiced. And despite being a well-known filmmaker, Agnes reinvented herself as a visual artist starting in 2003, when she created a video installation, Patapuia, for the Venice Biennale.

Although she had continued to make autobiographical films, she focused much of her late-life creativity on creating multisensory art installations, many of them expressive of the kinds of social concerns that occupied JR.

Agnès and JR started working on a film together. Because of her age, Agnès, who was then 87, was only able to spend one week out of every month on the road with JR. They didn’t necessarily expect to make a feature length film, but two years after they began their project, in 2017, they released Faces Places to general acclaim. It was to be Agnès’s penultimate feature film and the only one she made for which she would share credit as director.

Faces Places is not easy to summarize

The film depicts Agnès and JR’s road trips around France in JR’s utility truck, which doubles as a photo booth and spits out gigantic photographic prints from its side. When they first start off, though not quite sure of what to expect or even what shape their film will take, their stated goal is to meet, talk with, and document the lives of “ordinary people.” People like Jeannine, the daughter of a coalminer who is resisting the demolition of the decrepit brick buildings, now abandoned, that used to house miners’ families. “We thought that we could meet people and listen to them and listen enough that we would put them in the light, in a way . . . give them value by noticing and listening to what they have to say,” Agnès explained.

They go to relatively out-of-the-way places, talk to the people they encounter, take their pictures. They paste the resulting large-format photos on the facades of various community structures, including abandoned houses, the sides of shops, village walls, barns, and passageways.

As their friendship deepens, their excursions undergo a change. What started out as an attempt to shine the light on everyday people comes to also document the interaction of two creative souls briefly crossing paths on this planet, and their shared preoccupation with human rights, the power of images, representation, ephemerality, mortality, memory, and how and what one sees.

“I’m a wreck, my legs, my eyes. You look blurry.”

Agnès’s vision was affected by macular degeneration when she was making the film. She also knew that she didn’t have much longer to live (she died from breast cancer two years after Faces Places was released). Her declining eyesight, impending mortality, past friendships and earlier work—the inevitable passing of her embodied self—become the film’s main subjects. To the haunting beauty of Matthieu Chedid’s music, Agnès’s vulnerability emerges as the beating heart at the center of Faces Places, giving the film its gravitas and form. Allowing this to happen was a radical act of generosity on the part of an artist whose humanistic approach to her subjects has long been celebrated.

As depicted in the film, Agnès and JR’s lives can be seen as two parallel lines woven together in a daisy chain, held together by Agnès’s vision.

The first reference to her eyesight is in her opening scene. We see Agnès at a bus stop. She asks a fellow straphanger when the next bus is leaving and says she can’t see. Had the film included no other mention of her vision, we could easily have missed or dismissed the significance of that comment. But as the film progresses, allusions to her eyesight accrue. When Agnès and JR are discussing their project, for instance—allowing viewers to share in their act of discovery and creation—Agnès says, “I’m a wreck, my legs, my eyes. You look blurry.” At another point she mentions that, although she still has a driver’s license, she no longer drives, leaving us to infer that it’s because of her vision. (For many people with macular degeneration, one of the first and most difficult losses is giving up driving.)

Along with Agnès’s comments about her eyesight, we see gigantic eyes on the sides of cisterns (one of the stills from JR’s past projects), and JR wears dark glasses, glasses he won’t remove. Thus there is an unstated similitude and contrast between Agnès and JR. For both, their views of the world are distorted. Through no choice of her own, Agnès sees the world through blurred sight; of his own free will, JR sees the world through darkened lenses.

Vision is gradually revealed as the film’s core motif

About midway through the film it becomes clear that vision is indeed the film’s core motif when we cut from a scene at a fishmonger’s, where the camera lingers on the unseeing eyes of a monkfish, to a scene in an eye clinic. Agnès is lying on her back on a table. Except for one eye, her face is covered by a blue paper sheet. The hands of a medical practitioner, sheathed in protective gloves, affix a metal eyelid holder to her lids to prop her eye open and keep her from blinking. The doctor inserts a needle into the white part of her eye and gives her an injection. It’s a procedure that many people with wet macular degeneration undergo to help stabilize their disease, usually at regular intervals. The artists I know who get these injections dread them and usually feel unwell for several hours afterward.

After Agnès’s treatment, JR asks her if she was scared. She says she wasn’t because every time she gets an injection she thinks of the scene in Buñel’s film An Andalusian Dog, when a knife slices an eye in half along its horizontal axis. “So a shot’s no big deal,” she says. Still, looking depleted, she suggests they sit down.

In narrative voiceover, she explains that she has an eye disease and needs “injections, checkups and examinations.” What kind of examinations? JR wants to know. In what seems to me a deeply courageous act, she still wears the blue paper gown and cap of a patient from the clinic. She’s also wears the glasses-like part of a phoropter, the tool with lenses you look through when you go to an optometrist for an eye exam. Last but not least, she has on a talismanic medallion with two eyes carved into its silver face. It rests against her chest, as if both to ward off ill luck and to reveal herself as someone for whom sight is central. In answer to JR, she explains that she has to read a letter chart.

“You see everything blurry, and you’re happy”

Cut to a wonderfully playful enactment of an eye doctor’s Snellen Chart. People are arranged in rows on a public staircase, top to bottom. Those at the top hold huge letters and the people in each descending row hold smaller and smaller ones. The people holding letters on the bottom rows are blurred out. Agnès directs the entire lot, top to bottom, to jiggle the letters they’re holding so that they are constantly in motion, slipping and sliding, unstable. Yes, “Now I’m happy,” Agnès says. “That’s what I see.”

“You see everything blurry, and you’re happy,” JR says.

Ever looking for parallel construction, a grammar that inflected the voiceovers in all of her films, she says, “You see everything dark, and you’re happy.”

“With some distance,” JR says.

“Or from above,” Agnès counters.

Agnès’s waning eyesight reminds us of the waning of life

The scene at the eye clinic marks a turning point in the film. We learn that photographs of fish they’ve pasted to a factory water tower were dead specimens, who are now living “the high life,” as Agnès says. JR and Agnès’s visit to the market to shoot the fish is presented as great fun. Agnès uses a small digital camera, the two of them comradely sort through bins to find “beautifully disgusting” specimens. But though it all seems cheerful, one of the film’s other concerns becomes apparent: it is about mortality. Agnès’s waning eyesight reminds us of the waning of life.

From the beginning of the film, both JR and Agnès have been revisiting their respective pasts. Most of the places they’ve gone have figured in the history of one or the other of them. In the first half of the film, JR’s history largely determines their itinerary. He’s showing Agnès the places he’s executed public art projects, introducing her to people he knows or has heard about.

As the film goes on, it’s Agnès’s past that determines their travels.

Dogged by time, they go to Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer, the beach where Agnès took a famous 1954 photograph. It’s a beach JR knows, too. He likes to visit it on his motorcycle. During one of his excursions, he discovered a World War II bunker (a blockhouse that the Germans had built to defend the coastline). He’d long wanted to paste something to the bunker and asks Agnès to collaborate with him. Along with the usual issues that have tobe taken into consideration (the size and orientation of the bunker and type of equipment they’ll need to access it), they have to consider the tides. The bunker is partially subsumed when the tide is high, yet one more face of time and ephemerality.

Agnes wants to use one of her old photographs featuring Guy Bourdin, a fellow photographer and friend, who, along with Fouli Elia, she used to go on shoots with. Now dead, Bourdin often posed for her.

They settle on a picture Agnès had taken of him sitting on the ground, legs stretched in front of him, back resting against a beach shack.

By the next morning, the tide had washed his image away. “The wind always has the last word,” we hear Agnès say in the voiceover. “The image had vanished. And we’ll vanish too.”

A little while later, they visit the graves of Martine and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Agnès seems sad.

“Are you afraid of death?” JR asks.

“I don’t think so,” she says. “I think about it a lot, but I don’t think I’m afraid, though I might be at the end. I’m looking forward to it.”

“Really? Why?” JR asks.

“Because that’ll be that,” Agnès says.

Agnès Varda’s films give us a veritable gallery of vulnerable women

The fishermen’s wives and daughters in La Pointe Courte who endure such things as the death of young children. Cléo in Cléo from 5 to 7, who seeks sympathy from someone, anyone, as she awaits the results of a biopsy. Thérèse of Le Bonheur, who drowns, perhaps in an act of suicide, after her husband tells her he loves a second woman. Pauline and Suzanne of One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, who long to balance love, family, and selfhood. Émilie in Documenteur, who has separated from her husband and exists in a vacuum of solitary grief. The shopkeeper’s wife in Daguerrotypes, who appears isolated and silenced by trauma or early dementia. Mona of Vagabond, whose unwillingness to follow the expected course leads to her death. Jane Birkin in Jane B by Agnès V, enigmatically trapped between her desire for attention and approbation and her drive to be authentically present.

In general, she left herself out of the picture. But in The Gleaners and I (2000), she turned the camera on herself. Aside from a few brief appearances in Lions Love and the films she made with Jane Birkin, it was the first time she became the subject of her own work. Subject to her own gaze, her vulnerabilities began to show, with the apex being Faces Places.

Agnès Varda did not have to show us that her skin was like crepe paper. She didn’t have to tell us that her memory was spotty, her vision blurry, her strength flagging. That she thought frequently about death. She was a legend. She could have basked in the seeming inviolability and invulnerability of her stature until she died. And yet, she showed us she was mortal. Against the foil of JR, the camera that she had so decisively used to document the vulnerabilities of women in her earlier films, now documented hers.

We don’t generally share or value weakness

But Agnès could see that it should be. Our vulnerability, after all, is one of the few things that we all have in common.

On their last excursion together, Agnès takes JR to Rolle to see Jean-Luc Godard. He had been a close friend of Agnes’s and of her dear departed husband, Jacques Demy. Throughout Faces Places, he’s been on Agnès’s mind, since, like JR, Godard wore dark glasses.

When they get to Godard’s house, he refuses to let them in.

It adds yet another level of vulnerability to the already exposed Agnès. She and JR sit by the lake. She is crying.

JR tries to make her feel better. Her hands trembling, her tears continue to fall.

JR removes his glasses. An impish look flashes across her face. At last, JR has done what she’s been asking him to throughout the film.

“I don’t see you very well, but I see you,” Agnes says.

Yes, she does.

Though Agnès Varda’s retina has been compromised by disease, she still sees. It’s in her ability to empathize with the people she meets. Her willingness to allow “chance” its place in the creative process. It’s in her capacity to envision scenes that convey deep meaning. It’s in her propensity to free associate, play, imagine, invent, and share.

Further Reading

Agnès Varda’s Third Life as a Visual Artist

We interview Rosalie Varda, who helped her mother continue creating in the last phase of her career.

Read More

Leave a Comment