The Prismatic Dimension

July 12, 2015

We visited Dahlov Ipcar in Maine to talk with her about her career and recent loss of sight.

Over the course of ninety-eight years, Dahlov Ipcar has spent nearly every day in her studio, as she raised children, ran a farm, and suffered through cataracts. From her earliest memory, art has been so “natural” and integral to her life that she says she “couldn’t imagine living without it.” When she was growing up, her father, William Zorach, would be carving in one room of their Greenwich Village apartment. Her mother, Marguerite Zorach, would be painting in adjoining room. Meanwhile, Ipcar would be designing murals of animals and bullfights for her bedroom walls.

Ipcar had a spectacular artistic debut. In 1938, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) held an exhibit called Creative Growth featuring Ipcar’s young artwork, done between the ages of three and twenty-one (yes, three).

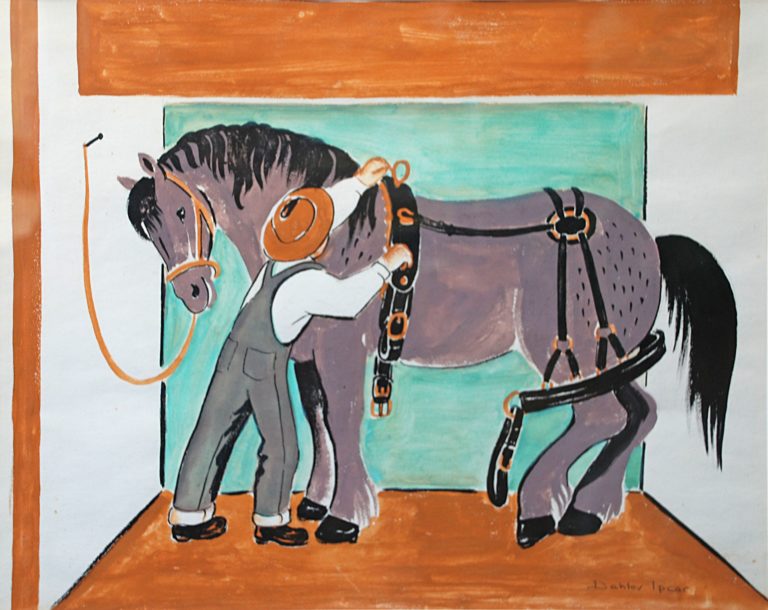

The exhibit ran in a newly opened exhibition space called the Young People’s Gallery, which was designed to serve the needs of art students between the ages of 12 and 18. Ipcar didn’t attend the opening. At the time, the exhibit didn’t seem important, and it certainly wasn’t central to the live she was living. She had moved to Georgetown, Maine by then, and was living deep in the woods where she had summered as a child, with her husband Adolph and firstborn son, Robert. The family grew their own food, repaired their own machinery, used oil lamps to read by and blocks of ice for refrigeration—scenes that informed Ipcar’s early, social-realist-style paintings.

But it wasn’t only that it would have been hard to travel to New York City for the MoMA opening. It was also that Ipcar didn’t yet consider herself an artist. Her children’s books, young adult novels, soft sculptures, and distinctive paintings of whimsical animals against cubist backgrounds (“non-intellectual cubism,” she calls her style) were yet to be created. Her philosophy of art—that it ought to bring new visions into the world—was still nascent.

Ipcar’s star rises (again) as her vision declines

Dahlov Ipcar’s presence in the public eye has fluctuated. But, after a period of relative obscurity, she is again exerting a quietly prominent presence in the art world. The Portland Museum of Art hosted a retrospective exhibit of her work in 2001. Her children’s books are being reissued by several different publishers to wide acclaim, including a rave review of Ipcar’s The Cat at Night by none other than David Eggers. And most recently, a small but significant exhibit of her work—alongside that of her parents—has been staged by Samsøn gallery in Boston and will be traveling to other venues this coming year.

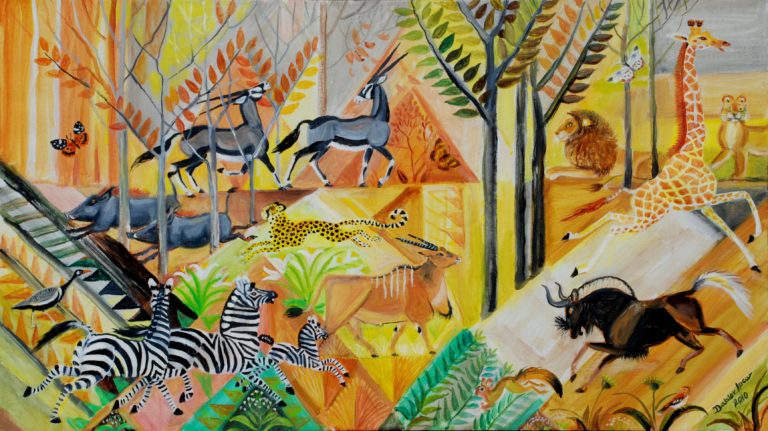

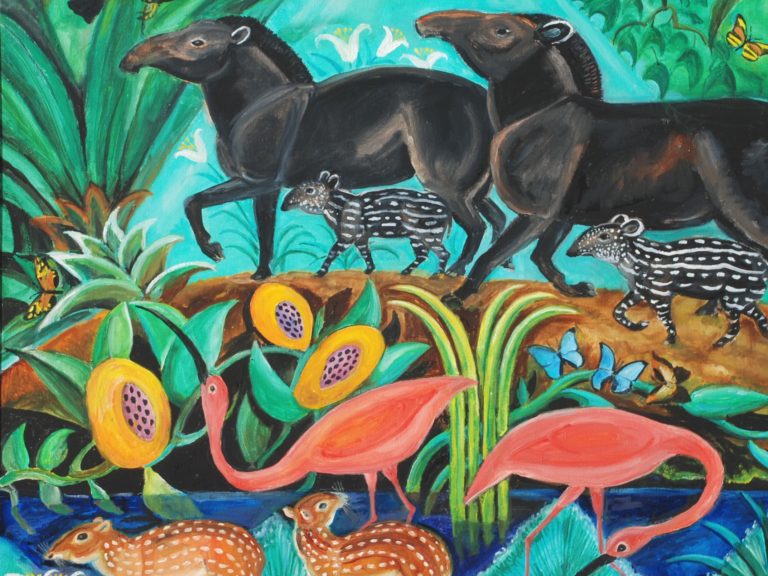

At the same time, her vision has been declining due to macular degeneration. When I called Ipcar to see if I could visit her in her studio, she fretted that the painting she was working on would be her last. It was of a panther and birds, she said. Animals have been a source of inspiration for her throughout her life, but, despite familiar subject matter, she was having trouble. She couldn’t see very well at all. Which meant, she said, that there was no interweaving of imagined foliage in her newest composition, none of the intricate designs typical of her work. She wasn’t sure what she was going to do, but I was welcome to come and have a look.

The impossibility of imagining a life without art

A few weeks passed between my phone conversation with Ipcar and the rainy Sunday in late June when I drove up to Maine to see her. She lives at the end of a one-lane dirt road that wends its way through woods in the town of Robinhood on the Georgetown Peninsula. The property belonged to her parents before it belonged to her. That it is a property that has been steeped in artmaking for two generations is immediately apparent. As soon as you step into the neatly kept house, Maine gives way to a potent menagerie of patterned textiles and wallpaper, paintings, marionettes, sculptures, and cloth figurines. Every surface shows evidence of the human mind and hand at work. It’s as if the house is a three-dimensional embodiment of Ipcar’s paintings and children’s books, where, among other things, Ipcar’s blatantly imaginative creatures come to life through prisms of color.

Ipcar uses a walker, but, aside from that, there are few signs that she is ninety-eight, so sturdy and present is she in body and mind, a woman nearing one hundred who found it invigorating to get along for years without running water, electricity, or central heat. She encouraged me to go before her through the small living room to the generous studio she and her late husband added to the house in the 1960s. She seated herself in front of a shelf of her father’s sculptures (many of which depict her as a young girl). As I looked over my interview questions, took out my notebook, and checked my recorder, she said nothing. Someone else might have asked about my drive or commented on the pouring rain, which clattered on the roof. She was not unfriendly. It was just that we had work to do. As her prolific career suggests, she clearly likes to work.

Ipcar had had macular degeneration for a decade, but until recently, it hadn’t significantly affected her painting

In the time that had passed between my call and visit, Ipcar had stopped painting altogether. “I was always happy when I was painting,” she said with straightforward honesty, “and I miss it. It takes a big bite out of my life.” Unlike some artists, who wish to conceal their vision loss, she was eager to discuss it, perhaps because it helped her process the loss.

She was first diagnosed with macular degeneration not long after her cataracts were removed about a decade ago. As is sometimes the case, for many years, the disease affected only one of her eyes, and she had little difficulty painting in the way that had long defined her. (It’s quite possible with monocular vision to manage the hand-eye coordination and retain the observational skills necessary for painting.) Though her doctor had warned her that she would probably lose her ability to discern color, her color vision held steady. Even as late as 2013 and 2014 her paintings, such as Hens in the Sun, were as colorful and detailed as any she did before.

For that decade when only one eye was affected, the only thing Ipcar found difficult about macular degeneration was how hard it was for her to distinguish between light and dark. Despite a wall of windows in her studio, she had trouble seeing details, even on clear, bright days. To counterbalance her diminished contrast sensitivity, her son Charlie had installed artificial lights, and that had helped a lot.

A worsening condition, then a deep fog, a blur

Time is a bit of a blur for Dahlov—aging and the sameness of days given over to the ritual of painting. But at some point in the past few years, she began having trouble reading and realized her condition was worsening. Then, in 2014, she wasn’t able to coordinate her hand and eye as well as she was used to, which made it hard to paint with the same level of detail she was used to. This was frustrating. She had always painted with relative ease, so wasn’t used to struggling with the brush. It was also a problem, however, because her signature style depended in large part upon intricately orchestrated patterns and finely wrought interconnections of geometry and form.

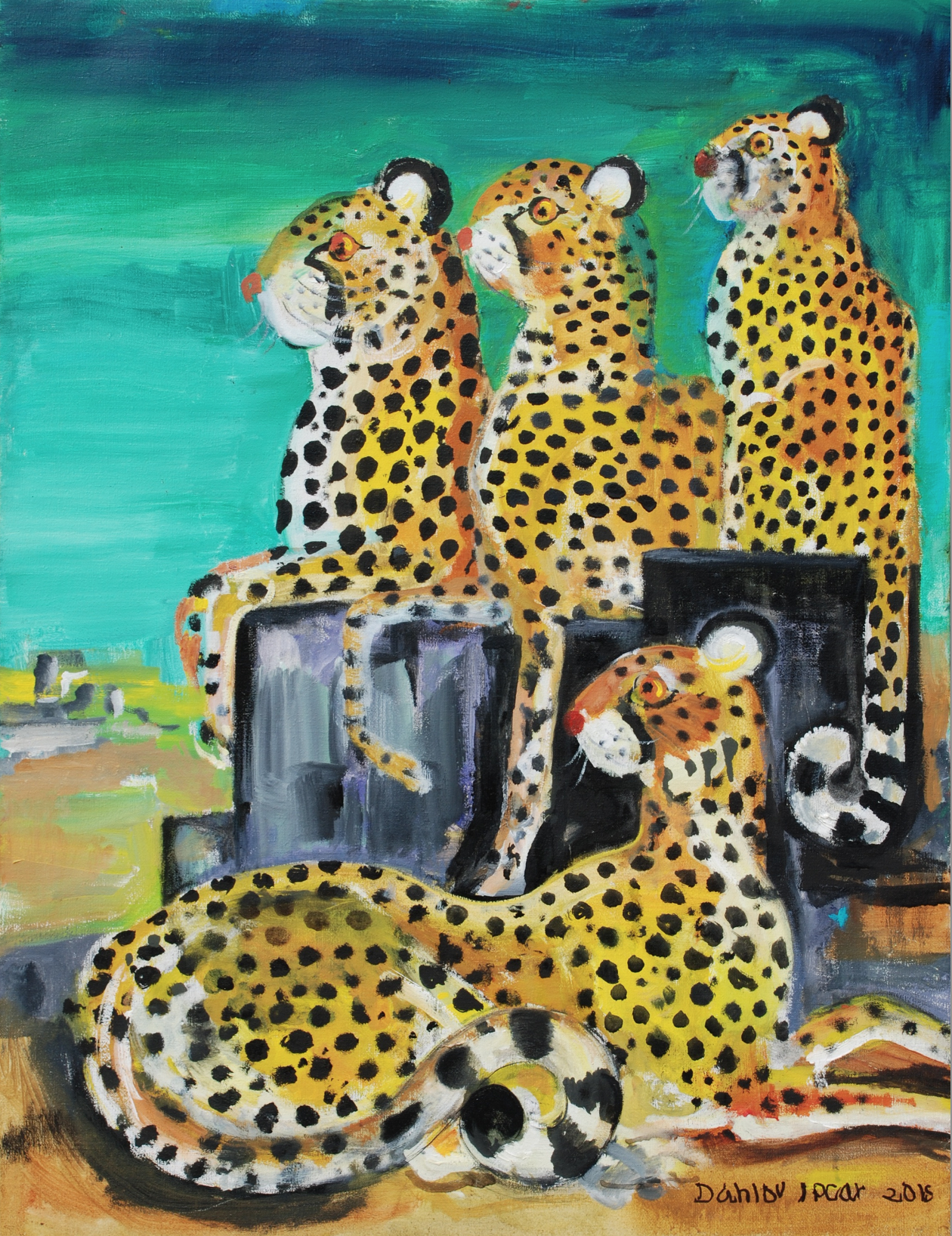

Unable to paint as finely, her paintings underwent a decided shift toward simplicity, as exemplified in Kings of the Castle. If Kings of the Castle had been created prior to 2014, the background and negative space around the leopards would be intricately patterned. Kings of the Castle is no less authoritative than Ipcar’s earlier work, but it owes its power to a monumental sense of presence that is different from anything Ipcar evoked before.

Unfortunately, at the beginning of this year, Ipcar’s eyesight declined further. What she calls “the fog” “came in,” macular degeneration’s blind spot, which replaces central vision as the retina deteriorates. As she described:

I’ve got the dry kind of macular degeneration, which they can’t do anything for. Supposedly the dry kind is better because it’s slower. Until this year, it has been slow, but now it’s been rapid. Seems like every day it’s worse. You are wiped out by the fog. I can see your white shirt, your arms and legs, but not much. I can just see they’re there, but your face and head are gone. Not solid black, just a very dense, deep fogginess. It gets into the middle of my vision when I try to paint. My hand comes up, and can’t see what to do because it’s just a blur.

Ipcar’s eye doctor told her that things had gotten much worse than he expected. As so many others have been told, there was nothing he could do.

“The hand knows a lot, but it can’t see through the fog”

Ipcar’s most recent works were arranged on easels in front of us, including a powerful and delicate painting of a panther and birds. “This is the last painting I’ve been trying. I started working on it about a month ago. I got this far, and stopped.” The painting she refers to is, indeed, of an entirely different ilk than anything she has done before. Even more than Kings of the Castle, the eponymously titled Panther and Birds moves more pronouncedly toward geometries that are larger in scale than in earlier works and form and figure that are simpler, less detailed. There is only the merest suggestion of prismatic background. This painting is among a small handful of other recent works that for the first time in her life Ipcar has been unable to finish.

“The hand knows a lot, but it can’t see through the fog,” she says, in explaining how she articulated the panther’s form by tapping into the magnificent, fluid line that her hand remembers but to which her eye can no longer return to contemplate, focus on, build upon, or adjust.

Mastery, calligraphy, mystery

Suspending judgment as to whether Panther and Birds is finished or not, there is much to admire in this painting: a mastery of shape, a calligraphy of brushwork, a mysterious composition that, though different from earlier Dahlov Ipcar paintings, still suggests, inspires, and satisfies. The unfinished nature of the painting reveals the hand and mind of the artist as her finished paintings never could. But that is not the only way in which Ipcar appears to be the subject of this work. One of the things that fascinates me about Panther and Birds is the way its main subject, the panther, looks out at us. I can’t shake the feeling that Ipcar is in that panther. That, like Rembrandt, Van Eyck, and Velázquez, Ipcar has placed herself within the scene and is gazing out at us. It’s remarkable that she creates this effect through the body language of a faceless imaginary creature.

Ipcar has reached out to the Iris Network (an organization serving visually impaired Maine residents), and hopes to adapt her approach to painting so that she can continue working. What did I know, she asked me, of how painters adapted to the disease? We talked about William Thon, whose work she admires, and his turn to black and white when he lost color vision because of macular degeneration.

After her son gave me a tour of the house, with its abundance of remarkable artifacts and works of art, I went to say goodbye to Ipcar. She was resting on a recliner. A fat calico cat, which looked as though it had sprung from one of her illustrated books, was on her lap. She invited me to the opening of her next exhibit of new work, planned for November 2015 at Frost Gully Gallery in Portland, Maine. She also said she’d love to talk more. Interviews and studio visits, which might once have been a distraction, were now a welcome respite.

Note: Some of the background information on Dahlov Ipcar comes from Carl Little’s The Art of Dahlov Ipcar and the documentary Dahlov Ipcar, which was produced as part of the Maine Masters Project, a film series profiling some of Maine’s most distinguished artists.

Leave a Comment