On the Presence of a Universal Material Narrative in the Work of Doris Salcedo

June 20, 2017

There are of course many ways to behold any work of art, a fact that is certainly true of the esteemed artist Doris Salcedo’s work, which has been widely exhibited and analyzed by art historians, cultural anthropologists, and curators around the globe. While the rich and varied dimensions of her work invite critique and dialogue on many levels, here we take a moment to appreciate her sensibility for composition and form, a place where the details and nuances of craftsmanship in her work are inseparable from its emotional impact and historical significance.

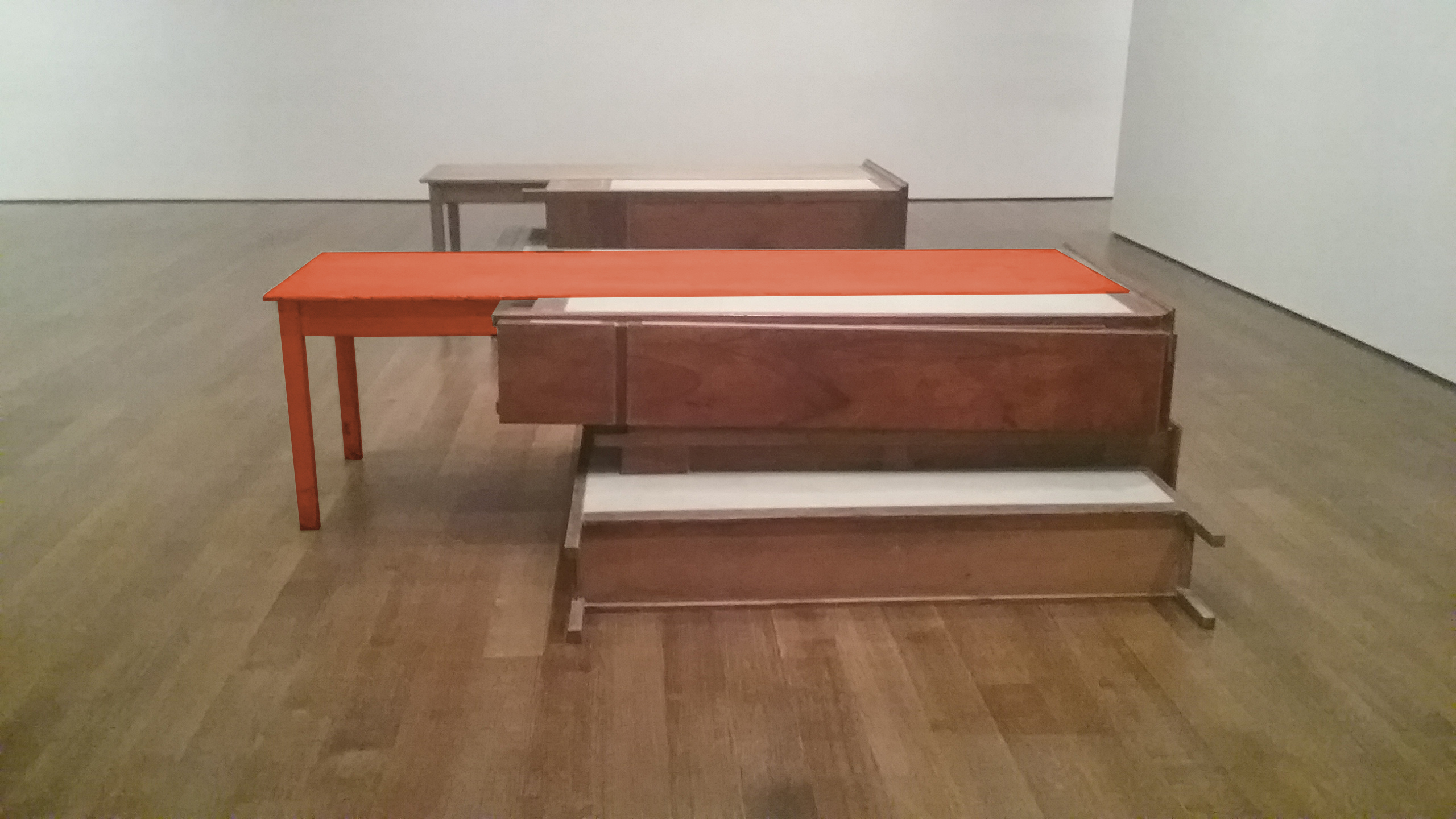

Of all the many pieces we could choose to examine, here we look closely at an untitled work from the recent exhibit, in spring 2017, at the Harvard Art Museums, not because it is unique in its own right (though it may be), but because it exemplifies her sensibility for marrying material narrative to tectonics, and in so doing for the capacity of her work to speak from the specific nature and specificity of assemblage.

In artistic contexts, the word tectonics refers to the nature and structure of materials that come together to create form. Modern architecture, for example, has a very different tectonic than Medieval architecture. The notion of tectonics helps us navigate the subject of materiality when it exceeds the rational condition of structural assembly—the moment when feeling, sense, poetics and narrative take hold of us, the moment when physical structure at once transcends structure yet remains inseparable from it.

Here above we see pictured one of Doris Salcedo’s untitled works, presented in “The Materiality of Mourning” in the Special Exhibitions Gallery at the Harvard Art Museums (November 4, 2016 – April 9, 2017).

If we abstract the primary formal elements of her work in color (as we have below, in orange and blue, for example), we begin to better understand the narratives embedded in her forms, to begin to perceive the presence of the table as that of a protagonist—a character that, visually isolated from the whole, can be known more clearly for what it is, a simple, unadorned domestic table painted white, chipped and worn over time. It is a familiar artifact now, which both by its positioning and its haptic presence imprints the work with a dominant though tranquil domesticity.

In so considering the artifacts and objects in Salcedo’s work as characters, we can begin to better understand them as existing within a dynamic relationship of cause and effect, and thus the potential for narrative becomes more clear. A conflict has transpired: orange prevails over blue, and both a formal and a philosophical resolution has taken shape.

Conflict, closure and transcendence are embodied here, as in much of Salcedo’s work. Disparate parts become one, and a unique form is born, familiar, yet new, unknown. Iconic associations assert themselves: table legs reach down and provide stability, the broad expanse of a flat, horizontal surface of a table top remains familiar and steady, the dents and scratches accumulated over time, holding memories of the plates and knives and coffee cups now long gone. The tabletop is a palimpsest, a record of the ghosts of generations past gathering in communion with food and drink.

As the work unfolds into this quiet narrative, the familiar and the unknown coexist, a perfect storm of past and present. It becomes evident that all was NOT once definitively well, even though, through Salcedo’s subtle understanding of the nature and personality of each artifact, the quietude of balance and harmony has been found.

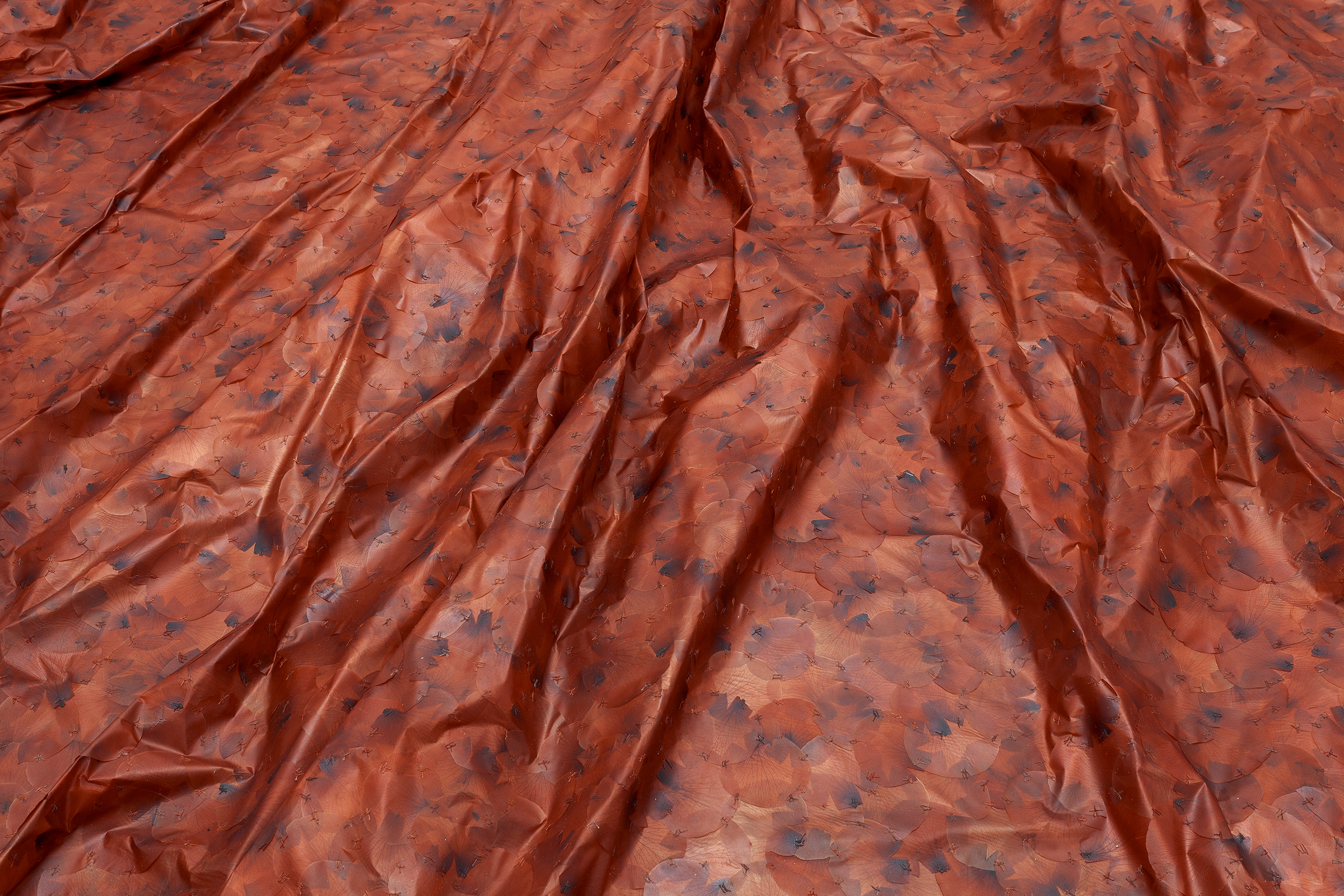

In many of Salcedo’s works, evidence of violence and conflict are neutralized and subsumed within a higher order, governed by material delicacy and precision. In this particular untitled piece, like Atlas condemned to carry the weight of the world, empty and anonymous, conspicuously bourgeois articles of furniture (highlighted here as a family of blues) are laid flat, piled one on top of another, stripped of function and grafted together to serve as a singular point of stability for the larger whole.

The table (orange) elides into the bourgeois mass of artifacts (blue), the former balanced and level, a clean datum formalizing the composition and referenced to no less than the horizon line itself, an assurance that chaos (and power) does not reign in this world. Materials are perfectly coped and scribed and joined, with a wood worker’s eye for precision, presenting a surgical pairing of two conflicting ideologies in which the whole exceeds the sum of its parts. Thus it is at least in part that Salcedo’s work embodies reconciliation, inspires, and speaks toward a hope for a better future. To the extent that Salcedo’s sight has been compromised by macular degeneration, her work affirms that clarity of vision is as important as clarity of sight.