Lost and Found: On the Working Methods of Robert Hamilton

October 22, 2016

Taken one painting at a time, as I had known his work prior to this summer, the artist Robert Hamilton’s work is if not playful then dark, peopled with eclectic, mythical characters floating in a liquid, dreamy depth of color, graphic, and shape. Surfaces appear haphazard and casual, and paint is applied with an ease bordering on recklessness.

When seen as a whole, however, over time, as I had the opportunity to experience at Studio 53 Gallery in Mid-Coast Maine this past July, an entirely different sophistication emerged, one imbued with clarity, cogency, and a perseverance to be at once measured and predetermined, and hell-bent on defying reason—even that of the artist himself.

Much probably could (and should) be read into the psychological and spiritual dimensions evident in Hamilton’s paintings, but for all of the speculation about free-associative symbolism and narrative that his work invites at first glance, when seen side by side, one painting adjacent to another multiplied over fifty paintings, it becomes clear that Hamilton was remarkably delicate and masterful with his execution, conscientious and fastidious about the surfaces and finishes he pulled into existence.

In the realm of painting, when considering qualities such as delicacy and fastidiousness, it is easy for me, a painter and a fan of precision in execution, to think of the perfection of Jean Dominique Ingres, or perhaps even the illuminated manuscripts of the Georgian Adysh gospels of 897, both clearly steeped in and dependent upon optical, visual acuity and precision. In this company, Robert Hamilton would not likely come to mind. Examined side by side, in fact, it would be easy to dismiss the presence of any shared sensibilities whatsoever.

Why does a work of art, a painting, draw our gaze? What, indeed, compels us to look and linger, to wonder and contemplate? Perhaps, I realized in this trip to Maine, and in encountering Hamilton’s work en masse in the way presented at Studio 53, perhaps it is the satisfaction gained at the intersection between knowing what to look for and the finding of what we seek. Here with Hamilton, for example, I had come to see Hamilton. I had not merely come upon Hamilton. There was intentionality in my encounter, and as chance would have it intentionality seen through the lens of an appreciation for and knowledge about Ingres and Adysh; unwittingly, I had come to see Hamilton with Ingres and Adysh on my mind. And what I discovered was that where with Ingres and Adysh we know and are habituated to look for qualities that we have learned to understand and expect to see (the sheen and drape of satin, for example), we may similarly approach Hamilton, to see his work, intentionally, and through a similar lens. Where Ingres and the Adysh gospels handsomely satisfy our expectations and preconceptions of beauty through the deft, seamless brushwork we know to look for, masterfully applied to evoke silk and satin and the implicit glory of gold and filigree, Hamilton may satisfy as well, for reasons very different but no less profound, sensibilities which if looked for will be found.

While this alignment with intentionality and a fine sensibility may place Hamilton in company with Ingres and the Adysh gospels (and in the most abstract sense may be the source of both the beauty and originality of his work), his and their work are not one and the same. Ingres remains an elite and fastidious, linear craftsman, and Hamilton a consummate problem-solver, improviser, and alchemist, an aptitude that allowed him to continue painting long after his vision had begun to fail due to macular degeneration.

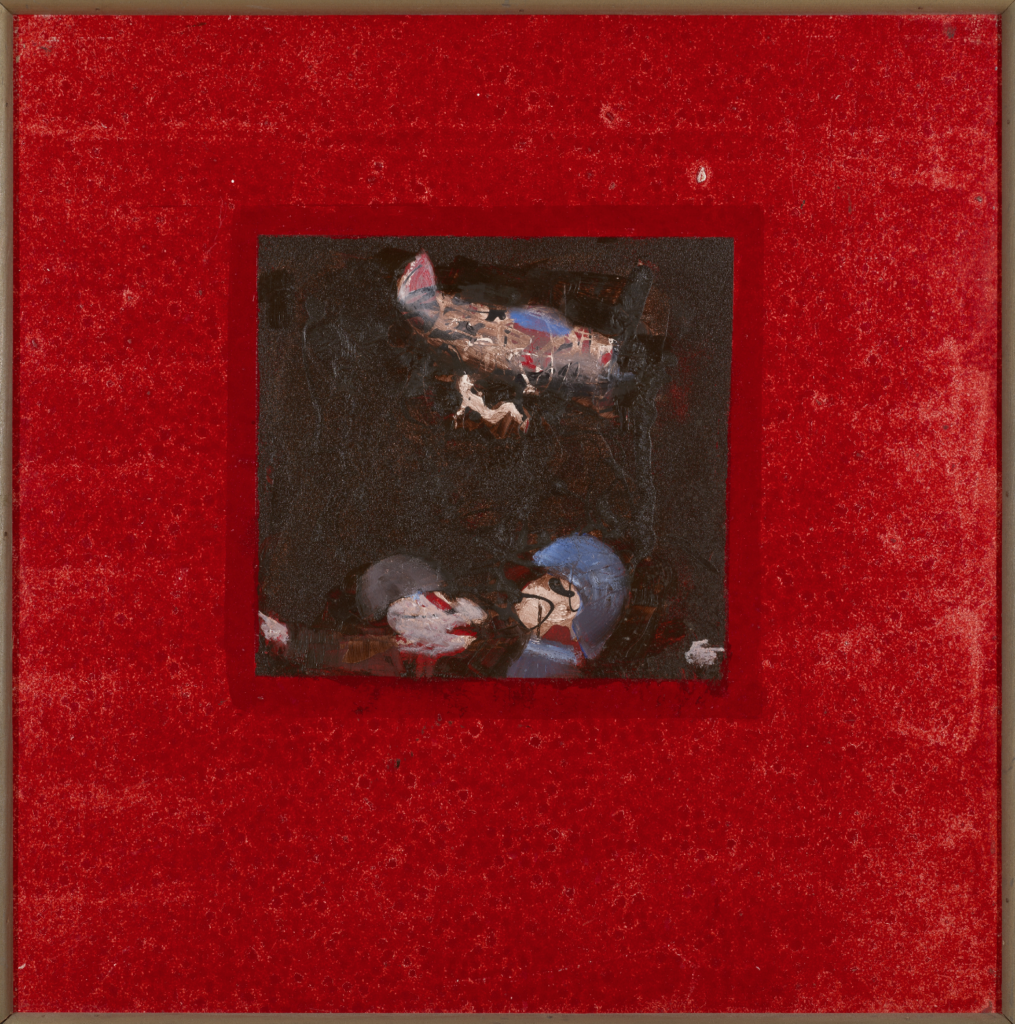

In Hamilton’s paintings, overt primitivism evokes childlike symbolism, an easy trope for failing eyesight to compose: soft shapeless figures, eyes the shape of footballs, intensely saturated color fields. Inseparable from this simple and visually crafted narrative, however, is the looming awareness that something else much greater is being encountered, something greater than the sum of the parts. Hamilton’s work, it feels, is more than just what appears on the surface, and it is so quite literally.

From a distance, simplicity speaks with conscious and deliberate narrative clarity. Figures face each other, airplanes sail silently off into the distance, balls bounce, fish swim. As one walks closer to the actual surface of his paintings, however, figures and shapes dematerialize and become increasingly abstract. Closer still, layers emerge from underneath, paintings long abandoned lurk under the surface, and like the negrido of alchemists long gone, fragments appear pulled out of the depths to augment and bring to life the larger whole of Hamilton’s vision.

Unlike Ingres, and others of like sensibility (those who built paintings additively, layer by layer, painstakingly refining edges and color relationships) Hamilton worked subtractively and spontaneously, mopping over old abandoned paintings with fresh, wet, often thick and textured, homogeneous skins of paint. He then scraped or wiped away shapes with rag or fingers to reveal fragments of the images beneath, now texture or pattern repurposed, the subcutaneous viscera within and inseparable from his final composition. His working methods intuited the natural, organic structure contained all around us and indeed in our very bodies—fecund and known, yet vast and unknowable.

What results in Hamilton’s paintings is figuration and form that is at once simple yet layered, quite literally, with remnants of the past exhumed and comingled with bits and pieces of the present. It is here in this moment where the interiority of that which is underneath juxtaposes with the present, surfaces wherein (or where-under) lie greater truths revealed, not Frankensteinian parts manifest in a patchwork quilt of stitches and mismatched skin, but the coming together of seemingly incompatible opposites, unified disorder fixed in time and space through a sureness of vision, where abstract lines and color cohere through the lens of overlaid, simple gestures, a place where what was the past now long gone (the surface underneath) fuses with a childlike innocence of the present (the surface). In combination this sophistication of finish denies simple explanation. The visual language remains purely visual, outside the syntax and structure of the written and spoken word; known and unknowable; fixed and ever moving; simple shapes commingled with rooty tangles, replete with contradictions.

“Bailing Out Again,” painted in a state of near complete vision loss, completed late in Hamilton’s life, exemplifies this phenomenon. On the surface, “Bailing Out Again” tells a story with simple gestures: a World War II plane flies in the background, a figure falls or jumps, two figures in the foreground confront and dispute. Yet we sense more, and see upon closer examination a wildness underneath that reveals the tangle of roots upturned, the fecund and shapeless dark matter of nature revealed, the skin of simple explanations peeled away to expose fragment by fragment the partial story of a larger, inexplicable whole.

Examined and understood in this way, it is perhaps easier to understand how Hamilton continued to create such vibrant works of art even as his physical vision failed. More alchemist and shaman, he worked from his inner eye.