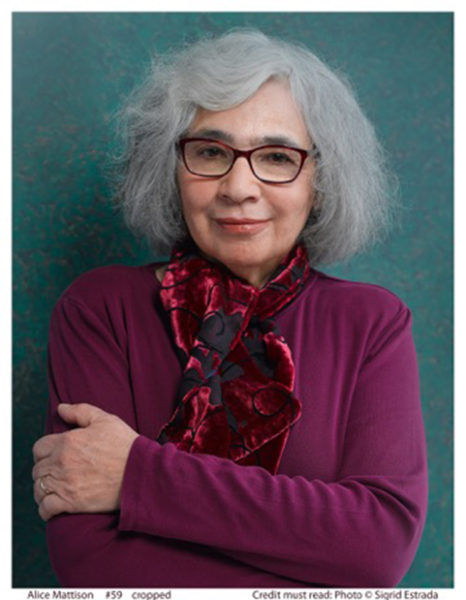

Ways of Seeing: An Interview with Writer Alice Mattison

March 29, 2022

In this interview, the writer Alice Mattison talks about her vision loss, which has changed her writing, teaching, and appreciation of art. It used to be that when she went to museums, she sought out the old masters. Now, she seeks out three-dimensional and abstract works of art because they welcome different ways of seeing.

Introduction: About Alice Mattison

In 1983, the writer Alice Mattison began to have eye trouble and was diagnosed with macular dystrophy, a genetic condition that, like age-related macular degeneration, leads to the disintegration of the center of the retina. Her left eye was less affected than her right and kept her going for many years. In 2010, however, her vision worsened, and she was additionally diagnosed with age-related macular degeneration.

Turning her immense curiosity to her changing vision and what she sees, she’s written several essays about her declining eyesight. In a 2018 piece for the New Yorker, she recounts the history of what she calls her “Eye Trouble,” capturing her complicated mix of emotions and the fascination she feels at what she does and doesn’t perceive. In a 2019 essay for the Paris Review, she writes about the trauma of visiting a museum and being unexpectedly unable to see one of the eyes in a Rembrandt self-portrait. And she recently published an essay at Electric Literature (2021) about how vision loss has changed what she reads, since she has no patience anymore for writing that isn’t concise, fresh, and complex.

In a recent Zoom conversation, she said low vision “is a problem, and sometimes I’m upset by it, but I’m more often just interested in it. It’s part of who I am at this point and has not impeded my life. In some ways, it’s made my life better.”

Mattison’s most recent novel is Conscience. She is the author of six previous novels, four collections of stories, a collection of poems, and a book on writing fiction, The Kite and the String: How to Write with Spontaneity and Control—and Live to Tell the Tale. Along with her writings in the New Yorker and the Paris Review, her essays, stories, and poems have appeared in Ploughshares, The Threepenny Review, Ecotone, and elsewhere, and have been reprinted in the Pushcart Prize, Best American Short Stories, and Pen O. Henry Prize Stories.

She lives in New Haven, Connecticut, and for many years has taught fiction in the MFA program in writing at Bennington College. She’s working on a memoir about her vision and her eighth novel, made up of stories, about a small urban arts colony called the Institute for Contradictory Phenomena.

In the following interview, based on a recent Zoom conversation, Mattison talks about how vision loss is entwined with her development as a fiction writer. She also discusses what three-dimensional and abstract art give to her as a person with flawed vision.

Interview

“We need less vision than we think”

Phillips: You write about how, a few years ago, when you were at Bennington, you speculated to a friend that we need less vision than we think. In what way do you mean that? What kind of vision do we need, and, conversely, what kind of vision do we not need?

Mattison: A remark of hers had made me aware of what I didn’t see. My friend pointed out something nearby, but I had to get close to see what it was. If she hadn’t spoken, I wouldn’t have known I was missing anything.

Actually my husband and I had a conversation about this very topic recently. He is about to have cataract surgery, and I predicted that he’ll be astonished at the improvement. I think he has adjusted to lower vision and manages quite well: he drives safely, reads, and so on. There’s an assumption that you need 20/20 to manage ordinary life, but you don’t, though it’s nice. My vision is much worse than his, and really bad in one eye, but I do all right, though I don’t drive. For a while, each time I noticed a deterioration in my vision, I thought the next change would force me to stop teaching, especially once I began to see a blank spot to the right of whatever word I looked at. But I’m still at it—though I admit that’s sheer stubbornness.

Phillips: You teach in the low-residency program, so must be reading a lot of student work. How many students do you have every semester?

Mattison: When I taught a normal load, it was five students a term, but five years ago I went down to three. That I can do. We see work once a month. I used to be able to respond to a student’s submission in one day. Now, often, it takes two. But that’s okay.

Phillips: When I read your essay in Electric Literature about reading, I was struck that you haven’t transitioned to reading on a device and don’t listen to books on tape. Reading is one of the first things many artists we work with give up when they start losing their vision.

Mattison: Reading with my eyes feels essential to me, as long as I can. I know that’s not a completely rational decision, and it’s certainly possible that listening to books would convey their contents more accurately than reading them the way I read now.

But I like seeing words, punctuation, and the design of a page; I like the privacy of solitary reading, without the voice of another person. I’m lucky to still be able to make a choice. By the time I developed age-related macular degeneration, which destroys central vision quickly, injections were available to keep it from progressing, and I’ve had many. Macular dystrophy, my original disease, is extremely slow, though there’s no treatment. I can’t read with my right eye at all, but though my left eye now has its own troubles, it still works. For several decades, I’ve needed glasses with high magnification to read fluently, and I’m open to reading with an electronic device, but I’m sensitive to light and have some trouble with computer screens, so an electronic device with a screen might be a problem.

“Vision is particularly hard to talk about and hear about”

Phillips: You write that, from the beginning, having eye trouble meant being misunderstood. Sometimes, you were misunderstood by doctors, not heard, not really listened to. Does having eye trouble cause you to be misunderstood in other ways, as well?

Mattison: There’s a two-part answer to that. First, I think almost everyone has trouble making their medical problems clear to others, and often we don’t quite believe one another. We imagine that the other person is exaggerating or just hasn’t seen the revelatory article we came across the other day. A dear friend of mine has heart disease, and I regularly misunderstand her or don’t quite believe her, maybe because I want her news to be better. For the same reason, I suppose, she keeps thinking the doctors may find a way to improve my vision, though all they can do is keep it from getting worse, if that.

But vision is particularly hard to talk about and hear about. If I look straight at your face on the computer screen, much of the left side is missing (usually I look a little to the side so I can see it all). That fact tells me nothing about your face, only about my eyes. Yet as a society, we persistently equate “what we see” and “what there is,” and our language is full of expressions like, “You can see with your own two eyes that such and such is true. . . ” “Eyewitness” news means accurately reported news. If we testify that we saw someone commit a crime, we can send that person to prison, though we may not have actually seen it, only expected to see it.

Possibly because people assume that what they see is indeed what there is, it may be easier to imagine not seeing—we can all do that if we close our eyes—than seeing poorly, and some people seem to think there’s nothing between perfect vision and complete blindness. Two extremely smart writers I know referred in a conversation to a book that was meant for “blind people,” which turned out to be in large print. People who know I read, write, and teach writing ask me if I can tell that this is a picture of their dog. Or, at the other extreme, they assume my trouble is nothing more than eyestrain. Or they think vision trouble must be trouble with acuity—if I got the right glasses, I’d be fine.

“For some reason the concept of impaired vision is difficult—and in truth, impaired vision really is a strange idea. My own seeing violates what we believe is true: what I see is not what there is.”

For some reason the concept of impaired vision is difficult—and in truth, impaired vision really is a strange idea. My own seeing violates what we believe is true: what I see is not what there is. Yet I could be called to serve on a jury. Sometimes I even think, if only for a moment, that what I see is what is actually there. Maybe it’s not surprising that people don’t understand. Vision, after all, is private. Other people really can’t know what each of us sees.

But that makes having flawed vision lonely. I can’t show you how your face looks to me. If I close my left eye and look at the computer screen with my right eye, I see a black blob surrounded by lines of what I know to be type but cannot recognize as type, bending toward the blur. So my right eye gives me no help with detail, and what I actually see is what my left eye, which has a few small gaps, sees: with my left eye I see the whole screen except for a couple of words just to the right of where I look, where there is a light gray blob. I would like to show you that—but I can’t. So really, it’s no wonder that I often feel misunderstood.

“To read a sentence I take many looks”

Phillips: Yet you write in such nuanced detail about your vision loss that I do in fact feel you’re sharing what you see with me. I’m thinking about how in “Eye Trouble” you write: “If you’d rather see smooth, reddish-brown wood, look to the left of a knob, and it will vanish. The detail goes away but the background color stays. That’s with both eyes open, or with the good eye. With the bad eye, two knobs, one above the other, disappear, and leave a dark gray blur. Nothing beautiful about that.”

Similarly, you walk us through what it’s like to read in your Electric Literature essay: “To read a sentence I take many looks, and may forget the beginning before I come to the end. Sometimes a word disappears into one of my visual gaps….”

What drives you to describe what you’re seeing with this kind of attention and detail?

Mattison: You’re a writer too; you know the answer. Why do we need to write down what we experience? Who knows? Maybe we’re born with a love of words.

Phillips: Speaking of words, you’ve written that vision is one of your favorite words.

Mattison: That’s partly a joke. But I am interested in vision, the word as well as its meaning. In fact, I just finished a draft of a memoir about my vision. In it, I mention my frustration when the word “vision” is used metaphorically. Of course, as an eye patient, when I see a headline with the words “blind spot,” or “vision,” I think it’s about seeing. But it never is.

Phillips: How long did you work on the book?

Mattison: I started making notes in 2016, when I first noticed small gaps in what my left eye saw—maybe a curve in the side of a rectangular picture frame. Because of the large central gap in my right eye’s view, subtle changes in my left eye made a noticeable difference. It was the most important moment since my eye trouble had begun. I bought a handmade blank book at an art supply store and started writing about it. I don’t remember when I decided it would be a book.

A newfound appreciation of three-dimensional works and abstract art

Phillips: You bring together a passion for art with a passion for literature, and have written movingly about art from the perspective of someone whose “eyes are damaged,” as you’ve said.

In your Paris Review essay you talk about how vision loss has made it harder to experience the old masters like Rembrandt and Vermeer. But, on the other hand, it’s given you a newfound appreciation of three-dimensional works and abstract art. What allows you to appreciate that kind of work more with damaged vision?

Mattison: I like that question. For many years, in a museum I’d walk slowly around a room, looking at pictures on the walls, while ignoring sculptures on tables. At the Metropolitan Museum in New York I went straight up the stairs to the European paintings, omitting Asian ceramics on the way. I did like African art—maybe it was the African art at the Met that made me understand that I could get keen enjoyment from three-dimensional art. And about twenty years ago I found a show of Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures in New Haven thrilling. But those were exceptions.

I always liked abstract painting, but I don’t know that I sought it out. However, it became more and more exciting to me, in part because I couldn’t even tell whether I was seeing it incorrectly. I became aware that some art almost announces, “There is one way to look at me, and you’d better look in that way,” and other art doesn’t. It says, “You could look at me in various ways.” That’s obviously true of a sculpture—nobody can see all of it at once. Even if the front is more important than the back, you can look at it from the left or the right. And if there’s more than one way to see it, then who’s to say that there’s something wrong with my way of seeing it?

With damaged vision, looking at the work of Barbara Hepworth, Agnes Martin, Joan Mitchell and other abstract artists

Phillips: Can you give me an example of a sculpture you’ve enjoyed looking at?

Mattison: There’s a big Hepworth sculpture in the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, “Sphere with Inner Form.” It’s a hollow iron sphere—bumpy iron, mottled—with large openings through which you can see a curved thing inside. It gives me a visceral jolt to see it, even to think of it. Walking around it, you can look through each opening and get strikingly different views. I like that, and I like its roughness—so if straight things happen to look a little bumpy to you, that’s not a problem.

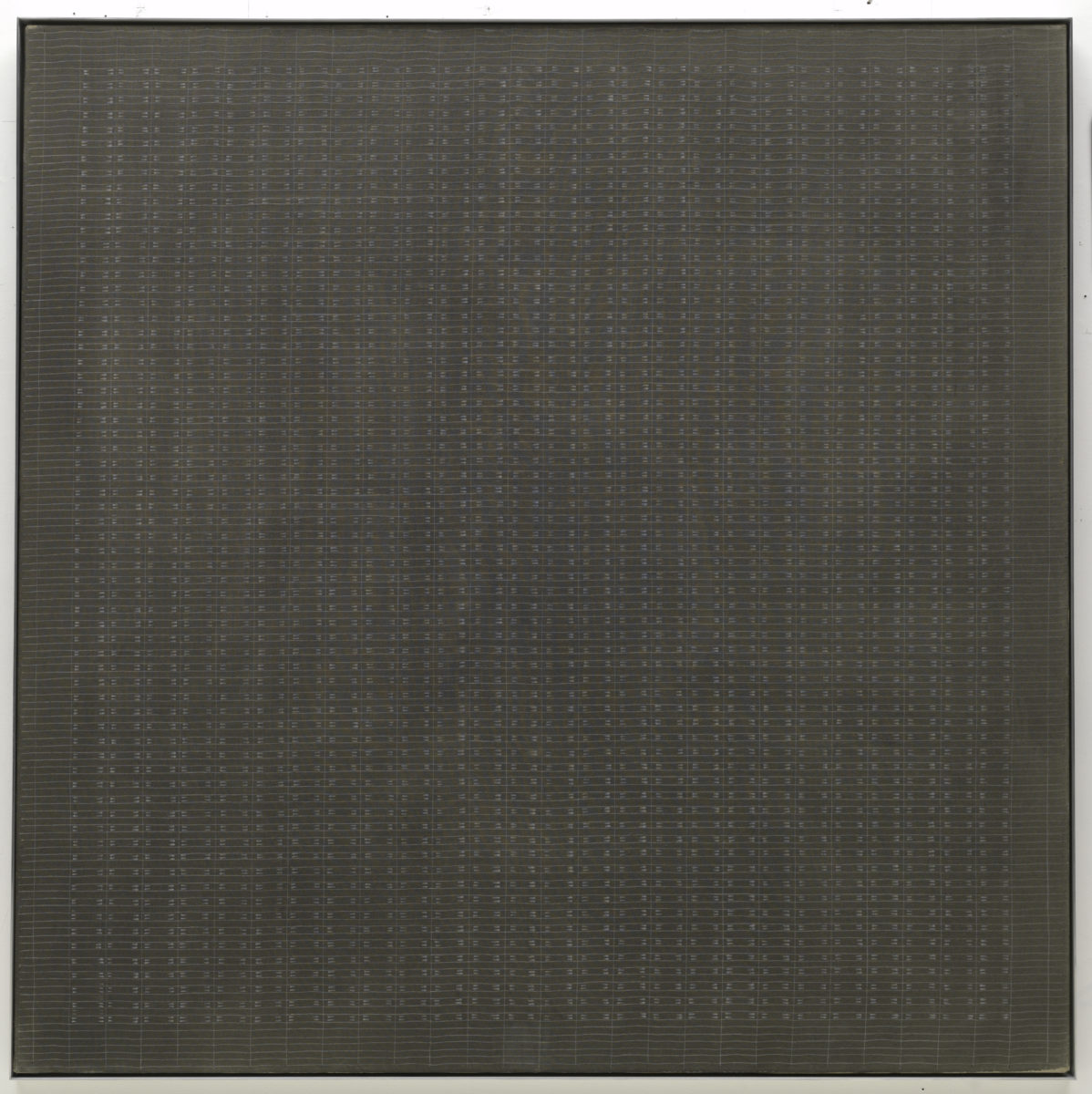

“You’d think that there was only one way to see Agnes Martin’s paintings because they consist of grids in pencil, vertical straight lines across the canvas, horizontal ones crossing them from top to bottom, with a wash of color. But in fact, they seem creative, not rigid, and not rational but emotional. I saw a show of her work when I’d recently begun to see noticeable gaps in straight lines, and realized that those paintings almost welcomed a different way of looking.”

Phillips: With two-dimensional work, you’ve written specifically about looking at Agnes Martin’s work.

Mattison: You’d think that there was only one way to see Agnes Martin’s paintings because they consist of grids in pencil, vertical straight lines across the canvas, horizontal ones crossing them from top to bottom, with a wash of color. But in fact, they seem creative, not rigid, and not rational but emotional.

I saw a show of her work when I’d recently begun to see noticeable gaps in straight lines, and realized that those paintings almost welcomed a different way of looking. I can’t quite explain why it seemed okay to see bulges and gaps in the grid. Maybe it was partly because they were abstract. When I looked at the Rembrandt portrait and couldn’t see his eye (I can, by shifting my gaze a little to the left, but it took me a while to realize that), clearly something was wrong. The guy has two eyes. You’re supposed to see them.

But if a grid has wavering lines, maybe that’s not a problem. Maybe some abstract art looks good no matter how the individual sees it, as some clothing is attractive on anyone, while other items require a specific body type and size to look as the designer hoped they would. I’ve learned that an abstract painting can be beautiful and moving even if I don’t see its colors accurately.

Phillips: It’s interesting to consider that there’s no right way to see with certain kinds of art.

Mattison: I just bought a book of paintings by Joan Mitchell. It includes paintings and details from them, and the details are just as gorgeous as the whole paintings. If you had limited vision, and could see only part of a painting, it would still be beautiful. If you saw only a small area of a Rembrandt self-portrait—maybe only the buttons on his jacket —that would not be so great.

Phillips: Intially, you were upset when you saw Agnes Martin’s works. But then that initial reaction became transformed (as opposed to your reaction to seeing the Rembrandt). How did that transformation occur? Was it in the moment as you were looking at the work, or later as you were thinking back on it, or a little bit of both?

Mattison: It was in the moment, as I looked. I was upset by the first few paintings because I saw gaps and bulges. But then I realized that it didn’t matter. I think I must have noticed that the painting was beautiful, despite the blemishes that I saw. My view was as good as the next person’s.

“The term ‘differently abled’ makes sense”

It’s a sentimental fantasy to think that disability doesn’t matter. It’s unfair to people whose lives are terribly limited by disability. But, in a sense, disability doesn’t matter. The term “differently abled” makes sense. My disability prevents me from pouring a cup of coffee if the mug has a dark interior; that problem vanishes if the interior is light. Most people can manage either cup—and maybe that’s all disability is: the inability to do what the majority can do. Which sometimes matters a great deal, sometimes not so much.

When the owners of coffee shops post their menus on the wall, how do they decide on the size of the letters? I suppose graphic designers know how large the letters should be, depending on how far away the customers will stand. If I can’t read that sign from the place where we all stand when we order coffee, or if a wheelchair user is too low to see the sign, we have problems. But say the graphic design industry happens to publish new guidelines. Maybe now neither of us has trouble ordering coffee. Art may be experienced differently by different people, but like the mug with the light interior or the menu with larger print, hung at a different spot, some art looks great even if you’re not quite standard.

Works by artists like Willem de Kooning set a new standard

Phillips: It’s almost as if the work that invites you in doesn’t depend upon being seen in a single glance.

Mattison: I’m reading a very interesting book right now, by Edith Schloss, called The Loft Generation. When Schloss died [in 2011], she left behind notes and essays, mostly about the 1950s art scene in New York, out of which this book was put together. It reads as if it’s one book, but it’s really a compilation by a very smart editor [Mary Venturini]. Schloss was married to Rudy Burckhardt [a Swiss-American photographer and filmmaker]. She wrote about the people she knew—Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Fairfield Porter, Frank O’Hara, many others—and how they all came to know one another.

The illustrations include an early Willem de Kooning portrait of Rudy Burckhardt. His features are barely indicated. It’s not too different from faces I see at times, and so it seems to welcome viewers like me. It sets a new standard. De Kooning painted it that way for artistic or emotional reasons, but when he leaves things out, it does imply that things can be left out. You understand, when you look at that picture, that Rudy Burckhardt actually did have two fully formed ears, but they’re not quite there.

The function of art is not to reproduce accurately what is seen

Phillips: This “new standard,” as you put, also proposes, it seems to me, the value of a source and engine of creativity that’s not simply the eye and the brain. I’m thinking of the Agnes Martin quote you cite in your Paris Review essay: “Say you went blind. Very depressing! But you would still have a very exciting emotional life”. Or what Doris Salcedo said in a V&AP interview: “For me art is a way of thinking, and in order to think you do not have to have perfect vision. For me art is an attempt to comprehend reality. Art is a way to expand the narrow definitions we have of what it means to be human. Art goes beyond my visual impairment—it is about empathy, and it is about a political and an artistic commitment.”

Like expressionist art, my own seeing is a kind of seeing rather than an error, a problem.

Mattison: The more I look at expressionist art, figurative or abstract, the more I love it for the fact that it doesn’t make a claim that this is precisely what you would see with your eyes, or that art’s function is to reproduce accurately what is seen. If you saw a portrait by Alice Neel, and then met the real person, you wouldn’t expect them to look just the way they looked in the picture. We know that Alice Neel is distorting in certain ways based on her feelings. Her portraits reveal emotion as well as physical detail—emotion of the artist or the subject or both.

Mattison’s writing habits

Phillips: As well as being an observer and reader, you write stories. What is the experience of writing like for you? Do you have to use any special adaptations to draft your stories? Do you write by longhand? What kind of process do you follow to edit and revise your own work?

Mattison: I originally drafted stories in longhand. Quite a long time ago it became troublesome to read and copy them, so I began writing first drafts on a typewriter and later on a computer. I can still write in longhand if I do it very slowly, and until recently I used longhand for line editing my own work and my students’ work. But now, unless I’m extremely slow and careful, I can’t read what I write. I don’t see whatever is a little to the right, so I write into a void and the result is a mess. I still use handwriting, slowly, for grocery lists and so on, but otherwise I use a computer for everything.

On the computer, I open only one file at a time, and stretch it over the whole screen, because visual clutter is so distracting that unless what I see is simple and unadorned—no message saying “Subscribe” at the top of the screen, no ad on the side—I can’t stay with what I’m reading.

Nowadays people have Facebook open in one corner, email in another corner, maybe two Word files at once. I can’t do that, but if I fill the screen with the file I’m working on, use a slightly enlarged font, and zoom it to 150, I’m usually fine. Sometimes the brightness of the screen makes it difficult. I still print out my manuscripts fairly often and circle or underline what I want to change—or make a note in the margin, which, often, I can’t read later—but that’s because I’m old; I wrote on typewriters for many years. More and more, I revise on screen, which is fine until an editor expects me to use Track Changes. That’s difficult for me.

“When my eye disease began, my fiction improved”

Phillips: Also in your essay for Electric Literature, you write about how when you began to find it harder to read, you needed concise, fresh, complex writing more than ever, writing in which each phrase presented something different.

You describe how hard it is for you to read. That difficulty makes you more aware of language itself, which is of course the tool of your trade. I understand that what’s happening to your vision can’t be described as good. But I was intrigued by the idea that it has perhaps deepened your relationship to your craft. That it has marked your writing, starting with its syntax. I wonder if you have any thoughts about that?

Mattison: Oh, yes. My eye trouble started just as I was learning to write fiction. Earlier I’d written poetry. My first stories were not particularly good, but when my eye disease began, my fiction improved. You could explain that in all sorts of ways: trouble makes us more open, more aware of our feelings, and so on. In the memoir I’m writing, I claim, facetiously, that I had to get the eye trouble in order to be a writer, that writing had to be particularly difficult or I wouldn’t have done it, and I think there’s some truth in that. I had little kids and a busy life. The only way I could write at all was to go at it ferociously, and the eye trouble made me extremely determined.

Phillips: It seems the way you read, with words disappearing, for instance, into visual gaps, might leave room for rich and interesting associations.

Mattison: Yes, it has made me more aware of individual words. I like crossword puzzles and word games—anything about words. I see them one at a time.

This morning I saw something in the newspaper about hip hop. “Hip” was at the end of one line, and in the time I needed to arrive at the start of the next one, I anticipated “hip surgery” or “hip problems.” “Hop” made me laugh at myself. Neither you nor I are denying my problem or the difficulties of people with worse trouble than mine—but ailments are also interesting: what they do to us, what they make us do, how they make us think. All of which is good for writing.

“I’m a more ferocious teacher than if I didn’t have the eye trouble”

Phillips: You’ve written about how your vision loss has affected your teaching, as well.

Mattison: I’m a more ferocious teacher than if I didn’t have the eye trouble. I read my students’ work so slowly that I can’t endure cliches, vagueness, unnecessary figures of speech. They’re paying good money to go to an MFA program, and most are delighted to have a teacher who scrutinizes their writing as intensely as I do—not all but most. The only way I can read is intensely. I need their work to be good, and it becomes good.

Phillips: They probably crave that kind of honesty and know it helps them to progress. In the process of drafting your memoir, did anything surprise you?

Mattison: I was surprised that art became so important to me as I wrote. I began reading about art, and groping my way to the understanding that expressionist painting approximates what I see, and that as it is valid, what I see is valid. That’s where I end the book, with the claim that like expressionist art, my own seeing is a kind of seeing rather than an error, a problem.

Further Reading

Hedda Sterne’s Recommended Books

Hedda Sterne was a passionate reader. We offer her refreshingly timeless book recommendations as captured in her correspondence with a friend.

Read More

Comments

Marvelous interview. The interviewer is so intelligent and sympathetic. The interviewee [funny word!] is so articulate and so cool. The art adds something important.

Alice Mattison’s words about reading and writing and taking in painting and sculpture have a lot to teach, not only about those subjects but, even more, about courage and commitment and dedication.

I am a huge fan of Alice Mattison, and thank you for this wonderful interview with so much insight, humanity, intelligence, and yes, humor. I will look at art differently and carry this conversation with me for a long time.

Leave a Comment