“There Is Such a Thing as Instinct in a Painter”

January 27, 2017

In the following excerpt from our oral history with Serge Hollerbach, the artist talks about what it’s been like to paint with low vision for the past two decades. He also talks about some of the art he loves.

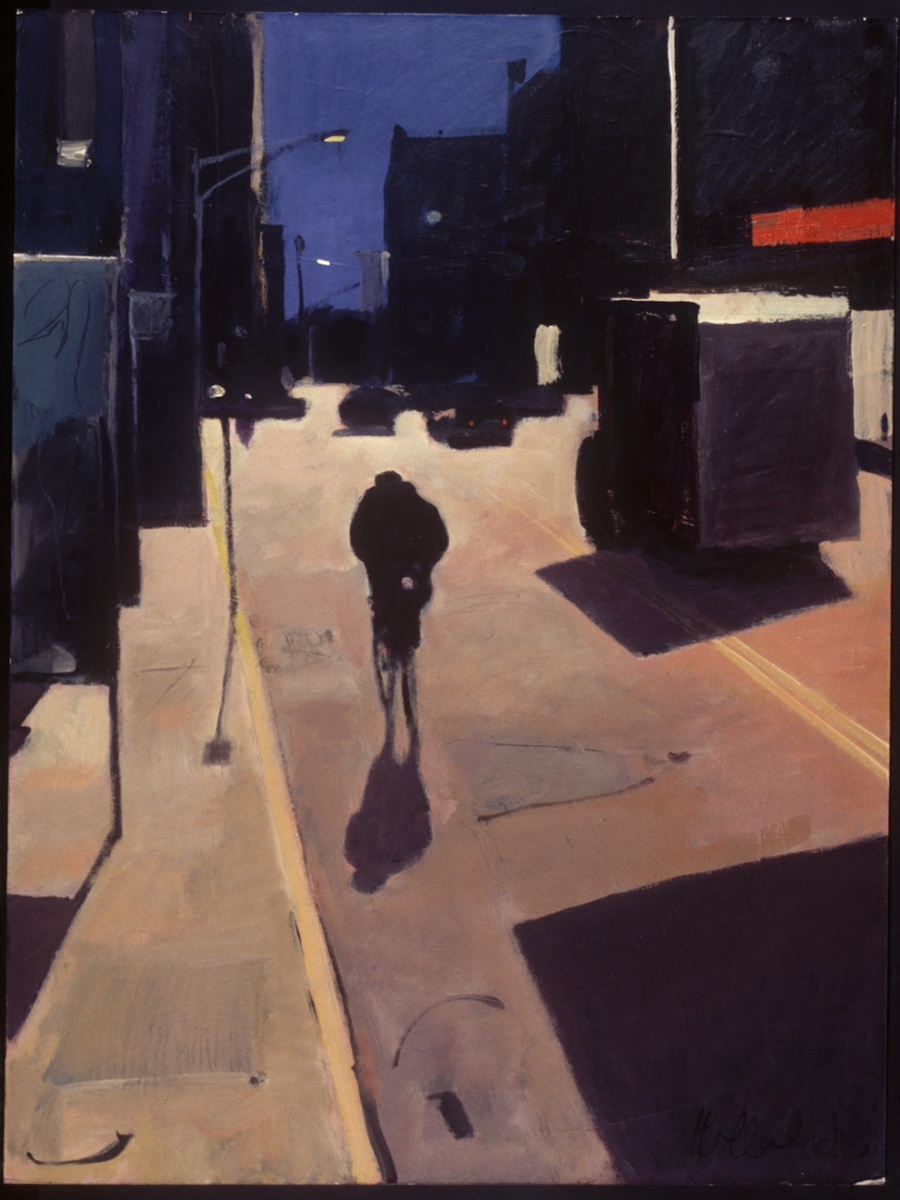

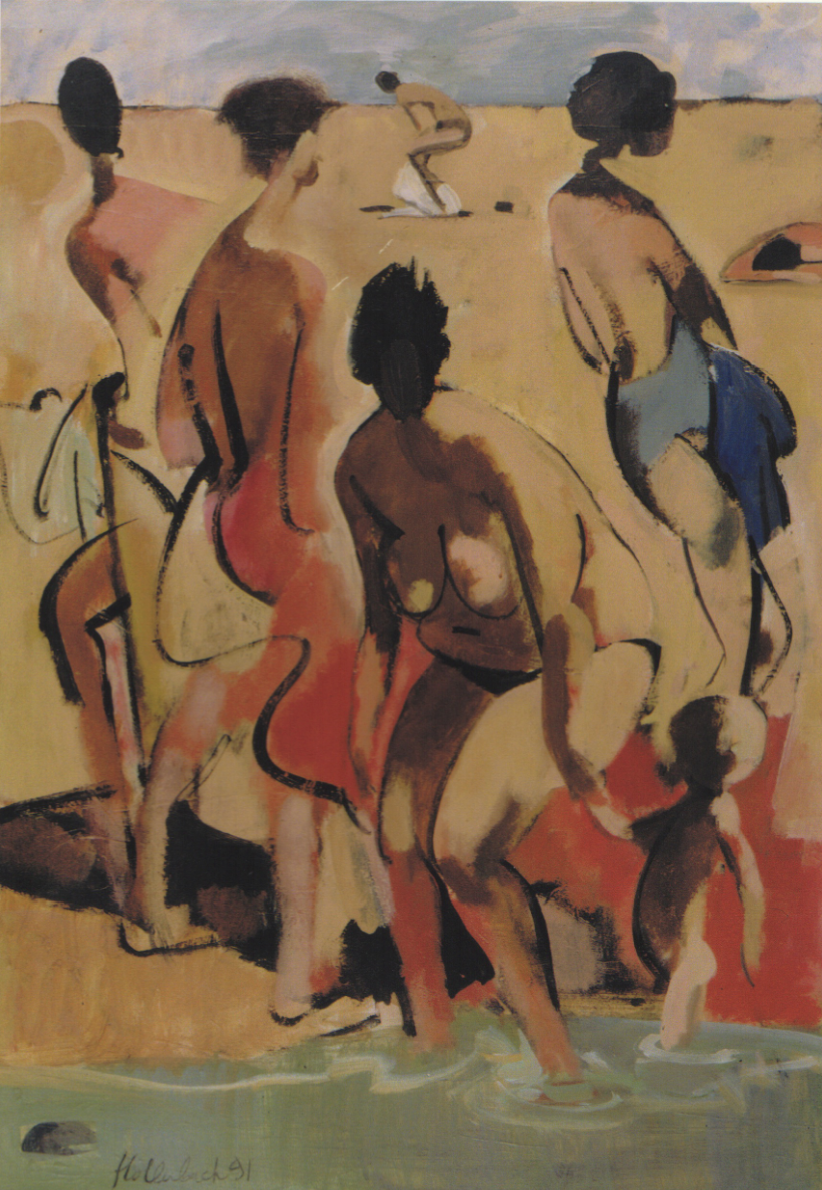

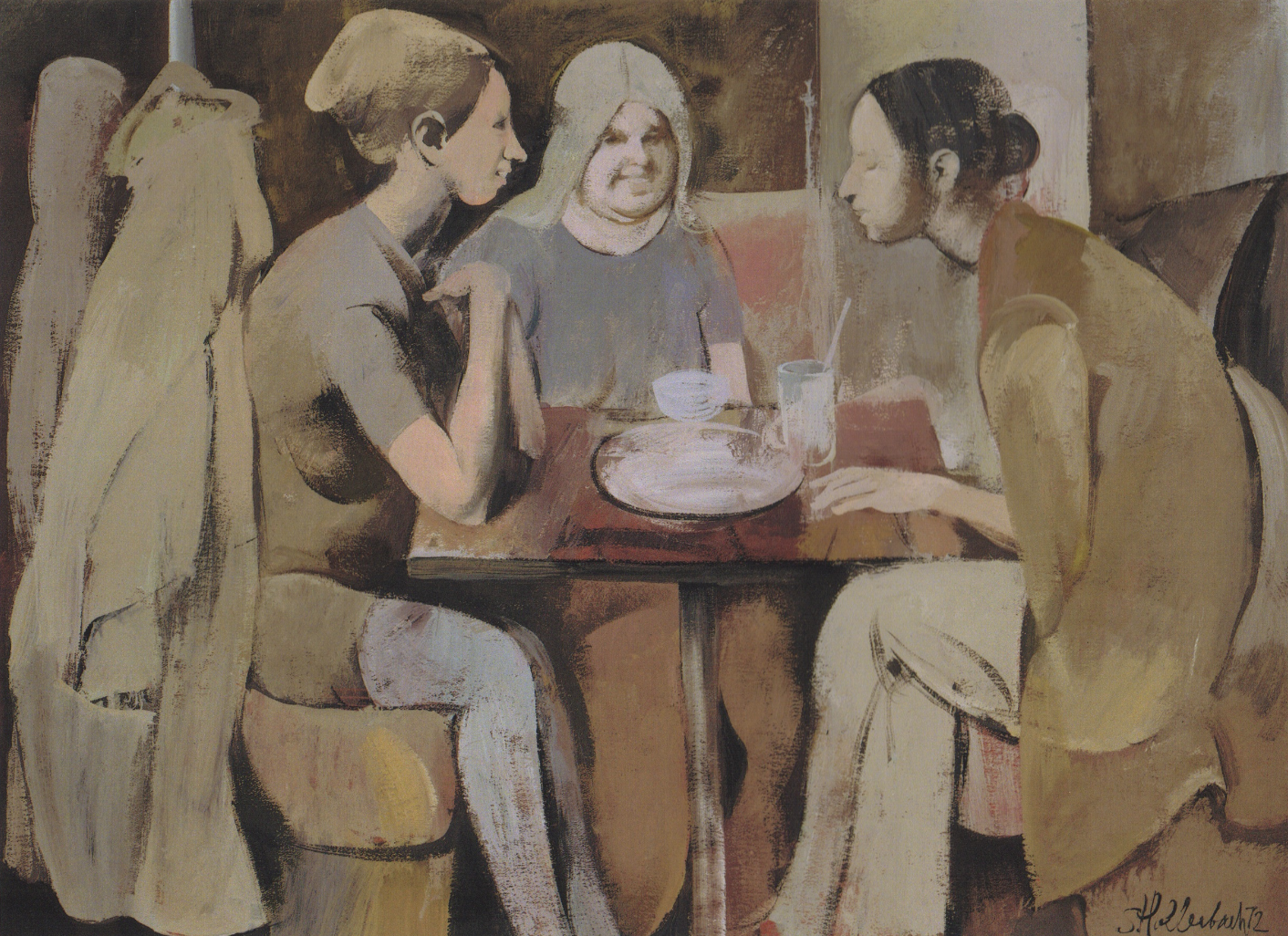

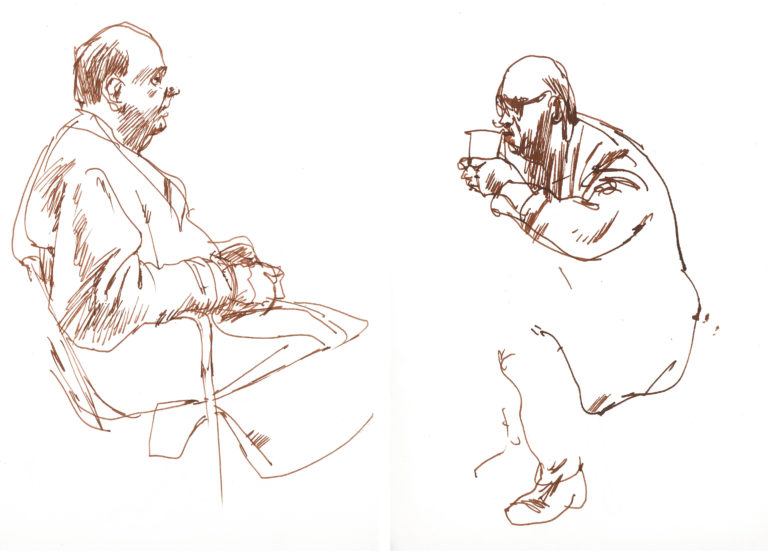

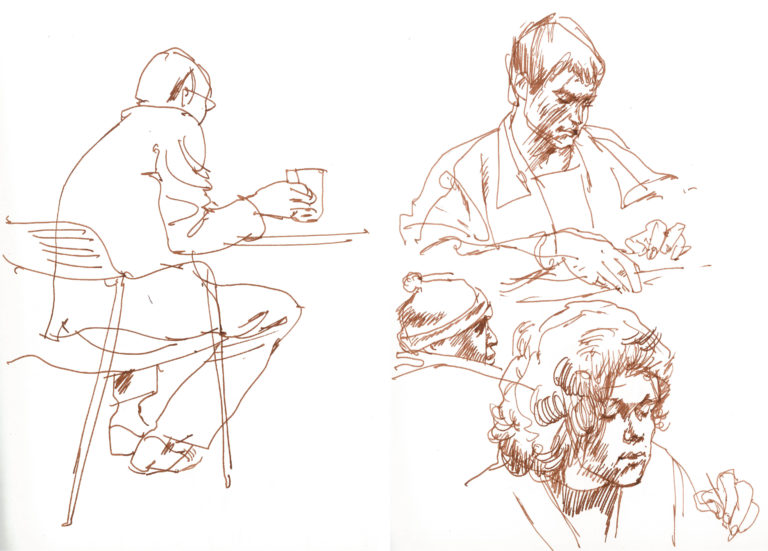

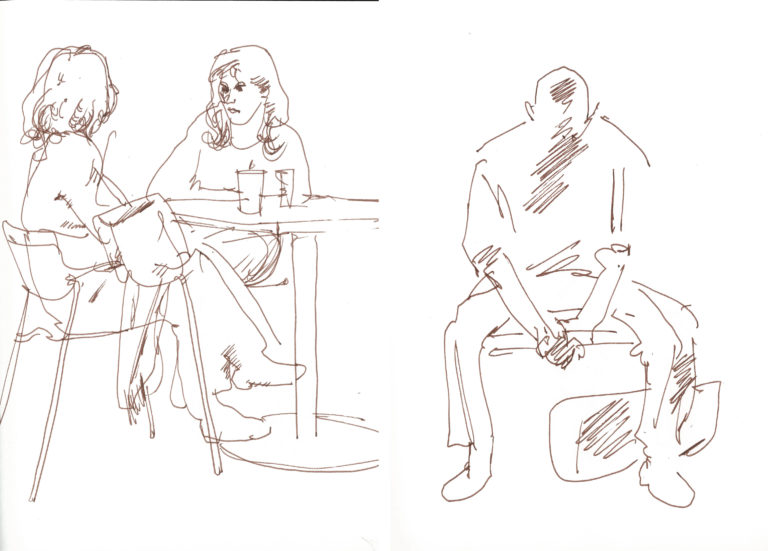

Earlier in the 93 year old Serge Hollerbach’s career, when he used to show his work regularly at galleries, he was known for his warm, empathetic, representational depictions of the world around him—a snowy Central Park, clusters of people on a New York Street, dog-walkers, strap-hangers, sunbathers. Yet, as much as his paintings were about representing the world around him, their graphic effect depended on an abstract conception of form, line and color—paint conceived of as shape—that was readily evident on the work’s surface.

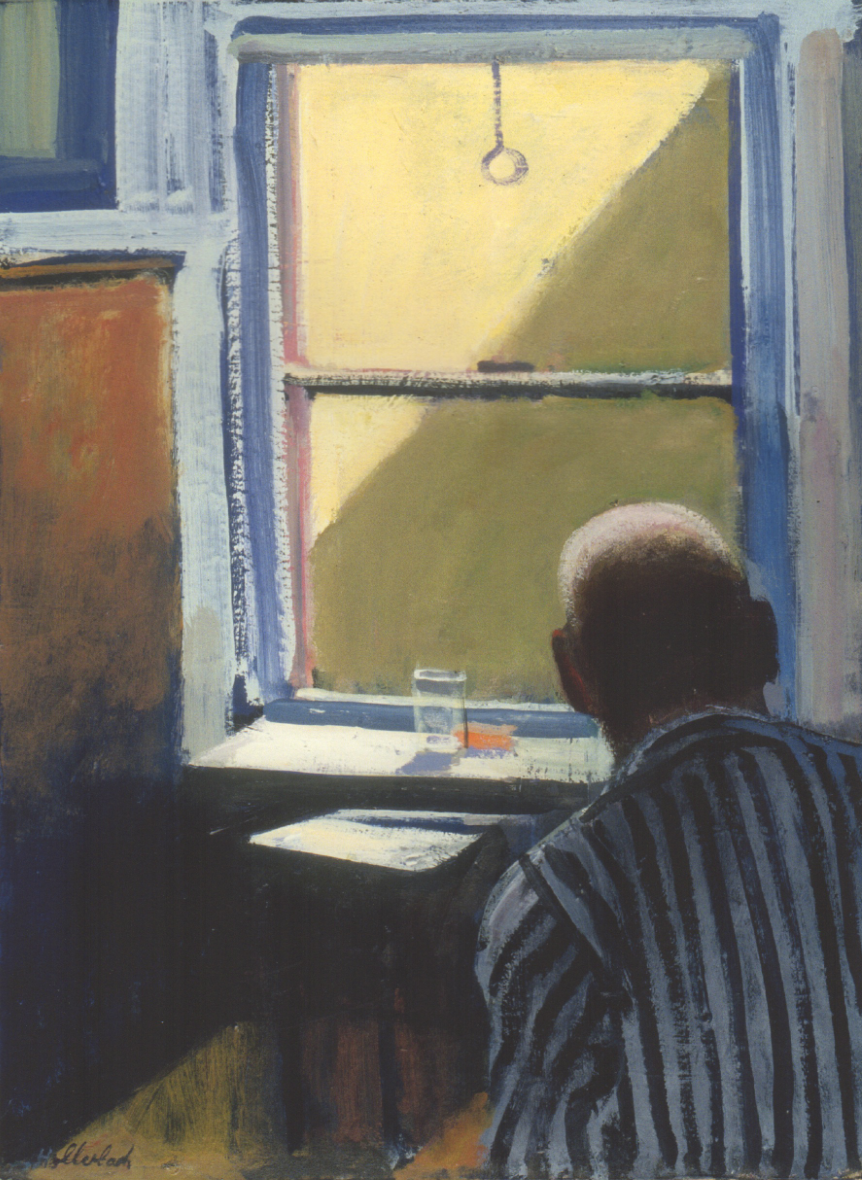

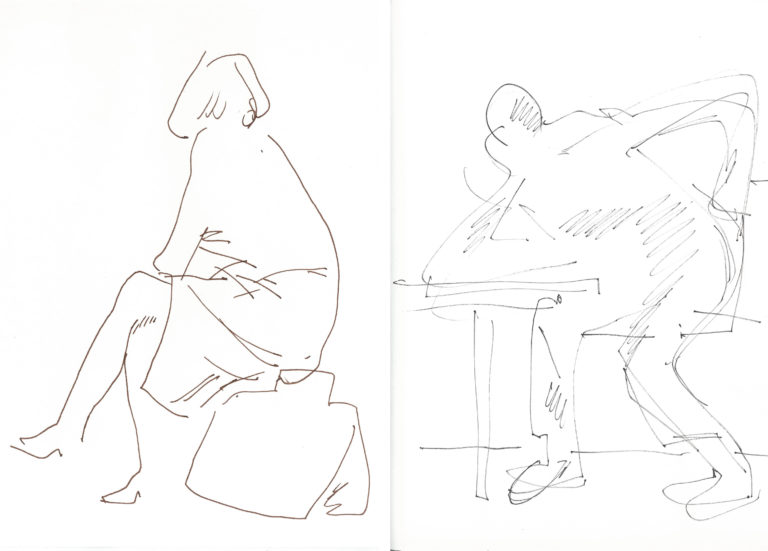

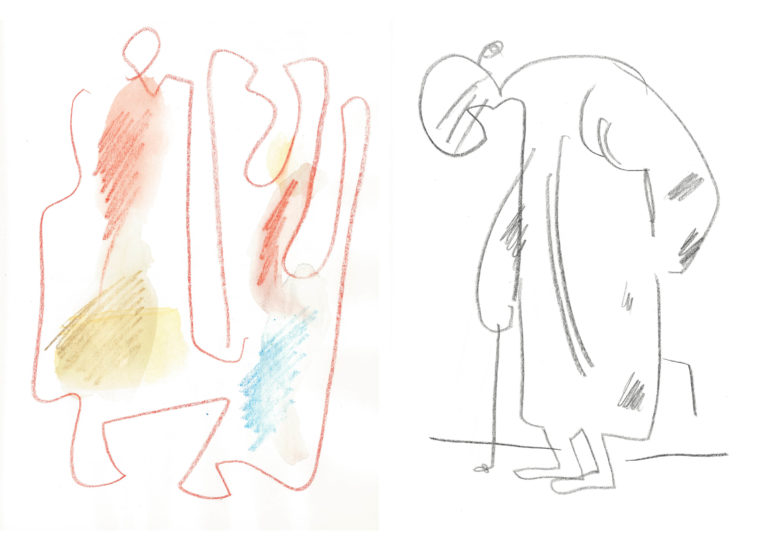

About 20 years ago, when Hollerbach could no longer see well enough to draw and paint in a detailed way, he transformed himself as an artist, and the abstract elements of his craft came more visibly to the fore. He still takes up street scenes, but now we notice first the shape, the color, the line, before heads, bodies, or gestures.

Hollerbach acknowledges that he has lost something, but at the same time says he feels “liberated” by blindness to pursue a bolder, more expressionistic vision than at an earlier point in his career, when commercial pressures and teaching pushed him in a more conservative, realist direction. As he discusses in the interview that follows (drawn from our more extensive oral history), he understands that his late work has but “limited appeal.” And yet he keeps working at it. He does so because painting provides “contact with reality.” Hollerbach feels he (and the rest of us) need that in order to survive.

Serge Hollerbach has lived a long life, one dominated equally by painting and his identity as a Russian émigré. He was born in Leningrad in 1923 and at the age of seventeen began to attend a special high school for art that was part of the Academy of Fine Art in Leningrad. In June 1941, barely six months into his studies, German forces advanced on Leningrad. The suburb where he lived was occupied, and he, along with many other Russian men and women, was sent to Germany and forced to work as a laborer in the factories.

After the war, he enrolled as a student in the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, where he was introduced to an expressionistic mode of working. He immigrated to the United States in 1949 and chose to settle in New York City, where he still resides. The professional life he gradually built included regular exhibitions, a job teaching at the National Academy of Design, and awards for his casein and watercolor painting. His work is in several museum collections, including those of the Yale University Art Gallery, the Butler Institute of American Art, and the Georgia Museum of Art.

In addition to painting, Hollerbach enjoys writing and has published books on the craft of painting as well as a self-published memoir, New York on My Mind: Memoirs of a Displaced Person that describes his early years as an immigrant in New York.

Oral History Excerpt: Serge Hollerbach

On Vision Loss and How It’s Impacted His Art

A’Dora Phillips & Brian Schumacher: How do you usually spend your days now? Do you paint regularly?

Hollerbach: I’m an artist, a writer, a cook, and a caretaker. My wife, who is 86, had two hip replacements and walks with difficulty. In the morning I go shopping. She has arthritic hands, she can’t even peel potatoes, so I cook. In the afternoon, I usually do something, either typing or drawing or painting, or making telephone calls, and then my social life is still, I wouldn’t say inactive. I’m honorary president of American Watercolor Society. On the 11th of April [2014] I’ll be at their annual meeting at the Salmagundi Club. And then there will be dinner. I will receive a prize of $500 for a small painting which shows the legs of a girl and a dog. It’s called Girl and Dog. It was done early this year. I like to say that only in America, blind people can paint and receive prizes.

Phillips / Schumacher: We know you’re legally blind, but what does that mean for you?

Hollerbach: Well, I see your face, but I have to come very close to you to, because I see you’re a nice young lady, let’s put it this way. But I couldn’t do a portrait, I couldn’t sketch you. I see everything in a blur. It’s out of focus.

Phillips/Schumacher: Is there a dark spot in the center of your eye?

Hollerbach: Yes, the central vision is affected. But my peripheral vision is also not that good. I see color the way I used to see it. No change. I didn’t lose the big shape. It’s the details.

Well, I do what I can. I don’t consider it a great tragedy. Of course some people say, “Oh Serge, for an artist to be blind.” I’m happy to be here and to be alive.

Phillips/Schumacher: When did you start to realize your vision was changing?

Hollerbach: My macular degeneration started in late 1994, one eye, this eye. I had laser surgery, and it got a little worse, but it was stabilized. I was still teaching at the National Academy of Design, but I decided that a one-eyed instructor is not a very good idea, so I quit. But I still gave some workshops where I could, you know, demonstrate a little bit. The last one was done, I think, three or four years ago in Rockland, Maine. My gallery there is Harbor Square Gallery.

Phillips/Schumacher: How does your vision loss affect your work?

Hollerbach: Well, of course, it’s obviously very frustrating losing the focus. It’s almost like getting out of water, and I have water on my eyes. I see a blur, shapes. But I still retain the sense of color. And now, my vision is basically stabilized. Getting a little worse, but it’s age. In three weeks I’ll be 91. So, my doctor said that the eye nerves are just aging. There was a period where these hemorrhages in the eye were active and so, for instance, the line went like a corkscrew. It would be a distorted line.

About five years ago an article about my work before and after macular degeneration appeared in Watercolor Magic. It was illustrated with an example of my early work, and then when I really started to lose my eyesight, and got sort of panicked and started to do kind of whites and reds. I can show you one of my paintings that I did over that period, without any realistic details.

Phillips/Schumacher: Is it still the case that lines appear wavy?

Hollerbach: No. Now that it’s stabilized, I see normal, except it’s foggy. And I can see television, sitting close to a television set.

Phillips/Schumacher: With your vision, I would imagine it’s very hard to see well enough to read and write.

Hollerbach: I type with two fingers. I have eyeglasses, I sit there and do this. So far, so good. My eyesight’s stabilized. My right eye was the good eye, but I was told, don’t have any laser surgery and so on, and all of a sudden this eye got worse. So my bad eye is my good eye; my good eye is my bad eye. They suggested I get some injections, but then my eye doctor says that if there is an infection, I will lose my eyesight. So, I don’t do anything. Just eating green, leafy vegetables.

I also have this thing, it enlarges type 30 times so I can read. Reading a book is difficult because it’s so tiring. You know, after several pages I have to sit down and rest my eyes. But I can read an article and write checks or any kind of business correspondence. I still do some writing.

It’s a very sad thing, but it is not a major catastrophe. It’s not glaucoma. It’s macular degeneration, age-related.

In a way, my vision impairment gave me new direction. I wouldn’t say it’s a blessing. But it gave me a new venue. I think that my visual impairment led me back to what I could have been.

Serge Hollerbach

Phillips/Schumacher: We see you have a New York Times over there. Do you read the news?

Hollerbach: My wife reads that and tells me what’s interesting, like articles about all kinds of art scandals. You know, the Knoedler Gallery went out of business. They sold fake Jackson Pollocks and Rothkos.

On other artists with macular degeneration: William Thon, Milford Zornes, Oskar Kokoschka

Phillips/Schumacher: You once met William Thon, who also had macular degeneration.

Hollerbach: In Port Clyde, yes. I met him. It was back in the early 1990s, I think. He walked on the side of the road because he, you know, didn’t trust his vision. And he told me that, he has a black table, and his wife puts a white sheet of paper, he can see the edges. And then he just does watercolor and pen and ink. And his subject matter was rowboats or sailboats and pine trees, and he almost painted them with his eyes closed. He was a very nice man, very dignified. When I met him, I didn’t yet have macular degeneration and felt sympathy for him. Later, he gave me hope. There is such a thing as instinct as a painter. He was working from instinct, and I realized I could, too.

And Milford Zornes [another artist who had macular degeneration], I was told that he taught practically to the end of his life. The first time I met him was in Springfield, Missouri, where we both served as jurors. When he learned that I had macular degeneration, he wrote me a very nice letter, expressing his sympathy. Huge letters on the page. He was obviously very blind. But he lived to be 100 and painted practically up to the day he died.

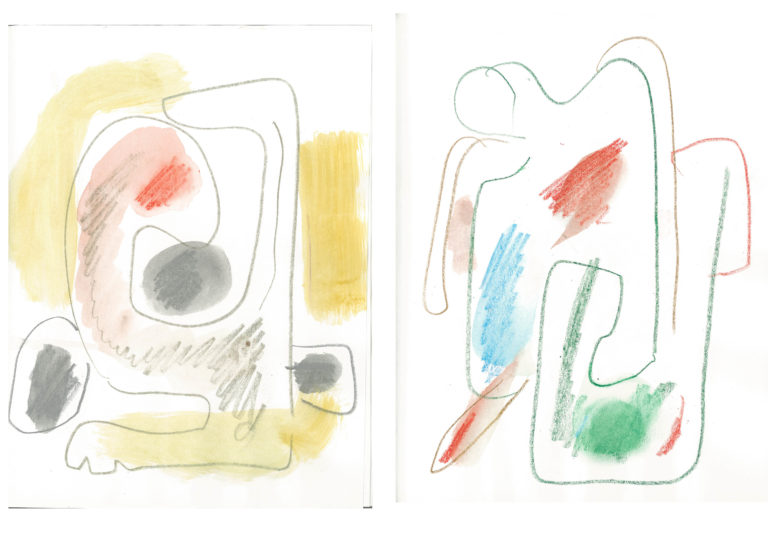

Phillips/Schumacher: This is an interesting painting, somewhat abstracted.

Hollerbach: Yes, well, you know, there was an artist, Oskar Kokoschka, you’ve probably heard of him. After World War II, he opened an art school somewhere in Switzerland called the Three Eyes Art School. Two eyes in your head, and then the inner eye. I am cultivating my inner eye in that one.

The inner eye

Phillips/Schumacher: What is the third/inner eye?

Hollerbach: I don’t know what Kokoschka meant, but I believe the third eye is the inner eye—something that your spirit, or your mind, or your soul, sees. It’s not physical seeing, it’s the inner seeing. And it is actually trying to make sense of what you’ve seen, and composing it. It’s a kind of a synthesis of what you have seen, and then you express it. By the way, I’m not, I was never interested in any ideology or philosophy, theosophy or anthroposophy, or whatever. It’s not in me.

I’m a strictly visual person, and so this is what my inner eye is, especially now that I’m legally blind. I try to express what I find most important in life.

Phillips/Schumacher: When you’re painting and working, is there some kind of physical memory you rely on to some degree?

Hollerbach: Yes, physical and also—an artist works, and the hand leads, or the brush leads the hand, you know, that kind of thing.

Phillips/Schumacher: How has your process changed in working now?

Hollerbach: I cannot do realistic work. What I’m doing now, actually, is more me because when I started to teach at the National Academy here at 89th Street, you had to do the right thing. And I became more realistic.

Phillips/Schumacher: So would you say your most recent work is actually more in tune with who you are as a painter?

Hollerbach: I think so, yes. I got more realistic than I probably would have been if I hadn’t taught.

When I studied in Munich, my teachers were actually German expressionists of the mild sort. The good ones. [LAUGHTER] Before they were killed or whatever. Actually, I didn’t know that one of my favorite artists, who immigrated to the United States, Max Beckmann, was teaching in Brooklyn. He died in 1951. I came here in 1949. But whether he was a good teacher, I don’t know.

So, a grotesque exaggerated depiction of human body, that was what I was taught. But then, if you don’t teach exaggeration to students, you can only suggest that you have to see the character. But this is pure pleasure for me now. I feel, in a strange way, that this partial blindness brought me a sense of liberation, though I know that this kind of work may find only a very limited appeal. So, I don’t care whether somebody likes me or not.

Schumacher: I’m curious about it and also sympathetic to your thought about coming into painting that feels more like you.

Hollerbach: Sometimes I just splash paint and see what it becomes. I do it for my own pleasure. While I’m doing it, I’m like a fish in water. I swim in it.

Phillips/Schumacher: But, were it not for your vision failing, just to be sort of blunt, you would not be doing this kind of work.

Hollerbach: No, not at all. In a way, my vision impairment gave me new direction. I wouldn’t say it’s a blessing. But it gave me a new venue. I think that my visual impairment led me back to what I could have been.

Phillips/Schumacher: Did it come easily, working this way?

Hollerbach: I’m not an abstract painter. I tried to find abstractions in myself, and I did not. Because doing an abstraction doesn’t mean that you are an abstract painter.

Phillips/Schumacher: Your recent works certainly stand alone as paintings.

Hollerbach: I call them painted drawings, almost. That’s an expression I invented, painted drawings.

On Making Contact with Reality through Art and His Complex Feelings about Religious Painting

Phillips/Schumacher: So, if you don’t mind our asking, it’s a very simple and a blunt question, but why do you keep painting?

Hollerbach: Well, I think that all creative activity is contact with the reality. You react to, you establish a kind of umbilical cord to reality. People who say that they don’t know why they live, they don’t love anybody enough, nobody loves them, they don’t know what to do, they commit suicide. And that is the reason. It’s establishing contact with reality, which nourishes us.

Whether it’s painting or music, dancing, writing, or for people who are not creative, collecting stamps or coins or working on their flower or vegetable garden, or having the bed to take care of. Ladies have little dogs and cats because you need connection for living. Because being completely alone is a terrible thing. And I know people who are completely alone, and they’re most miserable. They don’t commit suicide, but they are, they don’t know what to do with themselves.

And by the way, it has been noticed that people who have well, some kind of simple job while they are working, they are okay. Then they retire, and if they don’t find anything that they can do, they’re miserable. And they argue with their wives because the wife was used to being alone when the husband was working. They’re getting on each other’s nerves.

Phillips/Schumacher: Do you hold to a particular philosophy, when it comes to artmaking? Or anything you are painting against?

Hollerbach: I’m very much against over-intellectualizing art and trying to depict some kind of spiritual values, which you don’t know what that is. You know what spiritual values are in your personal life, your conscience and so on, but in art that would be illustration. And the worst kind of painting, I think, is a kind of ideological painting, whether it’s communist or whatever, fascist or whatever kind of ideology, but also, religious paintings.

But then again, it’s a very complex thing, religious painting, because they are obviously a depiction of nativity and annunciation and crucifixion and so on and so on. And yet, the Renaissance painters, they still derived so much from ancient Greece and ancient Rome. So, depicting the Virgin Mary was choosing a beautiful woman, never mind that she may have been a lover, Botticelli painted all madonnas, his girlfriends, but still, there was a connection to form. So, I think that saved religious painting, the best of religious paintings from being sort of corny, I guess.

One painting that I have always admired is a Dead Christ by Mantegna, where you see the head, the feet of Christ, he’s lying on a slab. It’s a horrible painting, and yet, it depicts a combination of physicality and the religious matter and the horror of death and everything. It has no sentimentality and no prettiness. But there is also, speaking about religious painting, there is also in the Catholic religion, this tendency to depict physical suffering to a point that is almost sadistic. St. Sebastian with arrows sticking and he’s smiling. Or by a famous German artist, Matthias Grunewald, his crucifixion of the body of Christ. So, there are many interesting influences between the spiritual world and physical world. Suffering, depicting of suffering. Glorifying suffering, or making suffering kind of cheap.

My mother lived in Kiev, which is the center of the Ukraine now, but it was a Russian city. She was a little girl, and she told me the following story. My grandmother was very religious, so on Sundays—my mother was six, seven years old—she had to go to church, St. Sofia Cathedral in Kiev, and stand all day, long mass, and my mother didn’t like that. But she told me that around the church, there were stands selling religious books and crosses, small icons. And there was a stand that sold rusty nails from the cross. Then the tears of the Virgin Mary in a little jar, and also an Egyptian darkness in the dark jar. And I think that these were conceptual artists. It’s amazing. People bought that, Egyptian darkness.

People need, this again, my homespun philosophy, people need to not only to visualize that, but to create images of what they believe. Actually, images that are seen that they can have in their hands. Religious sculpture and frescoes and everything. And again, it’s part of creative process. People who are not artists, I think they still need concrete images.

Phillips/Schumacher: What do you mean by concrete?

Hollerbach: Well, something that has texture, weight, and form. A rusty nail from the cross. Of course, any nail found in the garage. But a believer wants to believe that this is really the nail from the cross.

Phillips/Schumacher: And so, they suspend whatever disbelief they have about the credibility of that.

Hollerbach: Yes, yes. There was a joke that I read. A doctor opens his office, a young doctor, who put that horseshoe over the door. The horseshoe’s supposed to bring luck, as you know. So, the older doctor says, “Do you believe in that nonsense?” “No, of course, I don’t, but they say it helps even those who don’t believe in it.” [LAUGHTER]

This is the kind of thing for the rusty nail from the holy cross, or the tears of the Virgin Mary. And again, why is Mount Fuji a holy mountain? Why is Olympus the mountain where gods live? Form becomes content. And also, it is one of my fears. I even wrote a little article about it, but in Russian. Lucifer is obviously the rebellious angel who brought enlightenment to human beings, but he was a rebel. Of course, the church condemns him. But people had all kinds of beliefs, belief in God and so on, but also superstitions. For instance, mermaids and kings of the sea—Neptune, Poseidon—and then all kinds of leprechauns, and swamp spirits and the witches who live in the forest and so on. These were artistic images. For instance, when there’s thunder and lightning, the gods are angry and when you hear thunder, it’s the prophet Elijah rolling in his chariot.

Now we have weather forecasts. The artistic images are gone. So, in many ways, education kills artistic images. Superstition, as bad as it is—and I’m not saying we should go back to it—had an artistic side to it. Mermaids and Neptunes and leprechauns, house spirits. Leprechauns is Irish, right? And in German, there’s the heinzelmannchen and dwarves.

We need that. People who believe in nothing—no dwarves, no leprechauns, no spirits, no mermaids—that’s artistic impoverishment.

For more about Hollerbach’s life, stories about his experiences in New York, and his thoughts on art, you can find the full transcript of our oral history here.

Leave a Comment