Robert Birmelin: Weaving a World of Reality and Dream

July 10, 2022

The artist Robert Birmelin lost nearly all vision in his left eye due to macular degeneration in 2016. Because of his vision loss, he’s using drawing these days to continue to explore his unique vision of the world. A world based on reality that often feels like a dream—or a nightmare.

“If you wish to get hold of the invisible you must penetrate as deeply as possible into the visible”

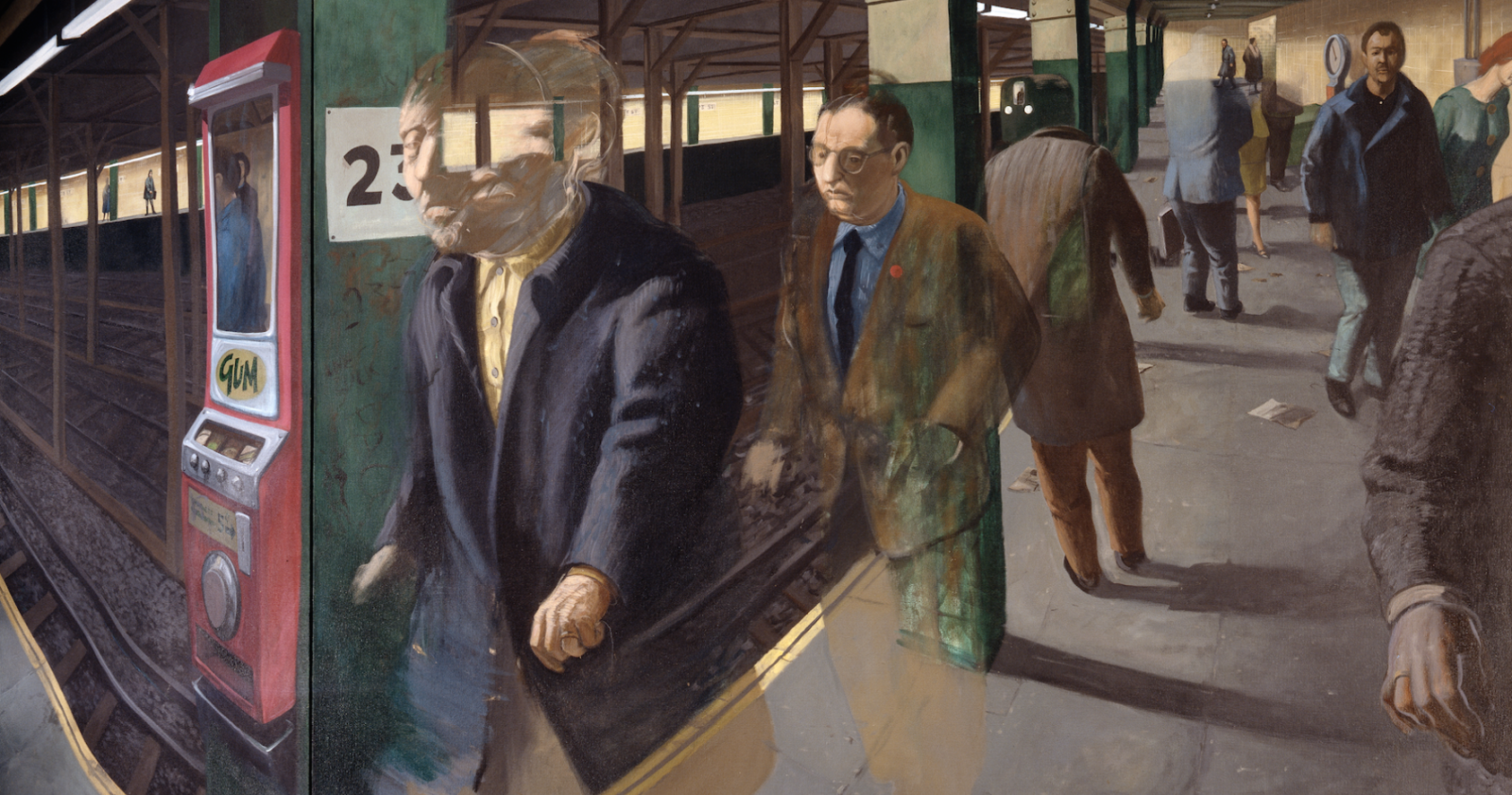

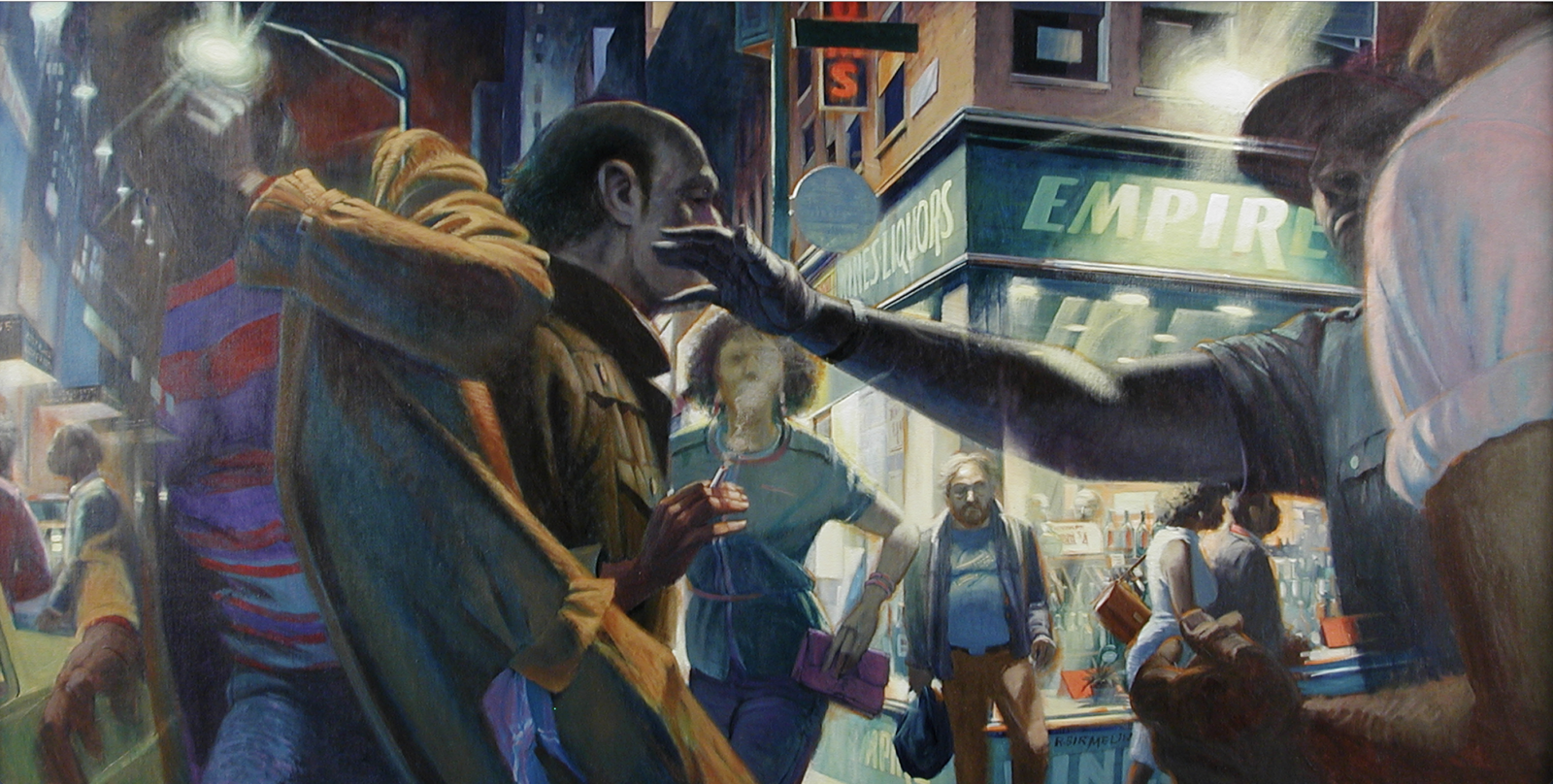

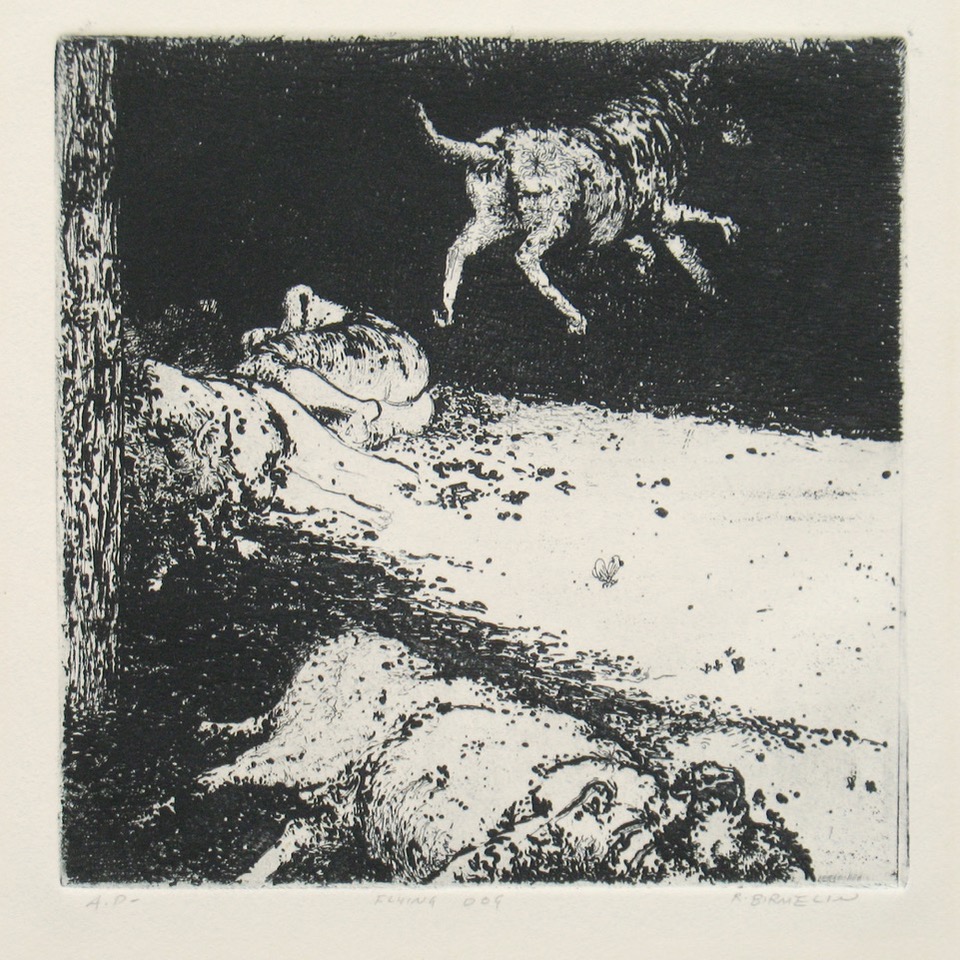

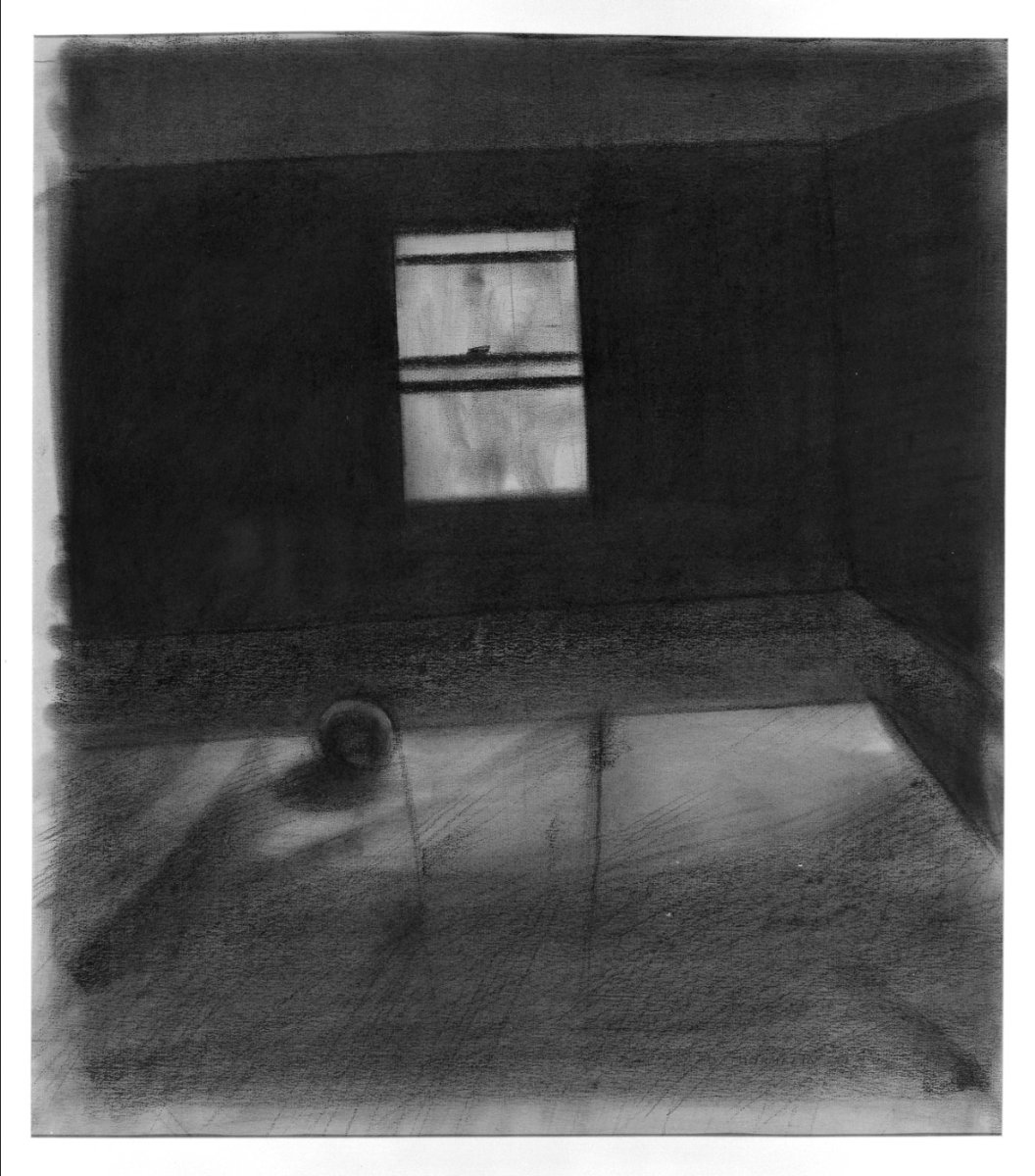

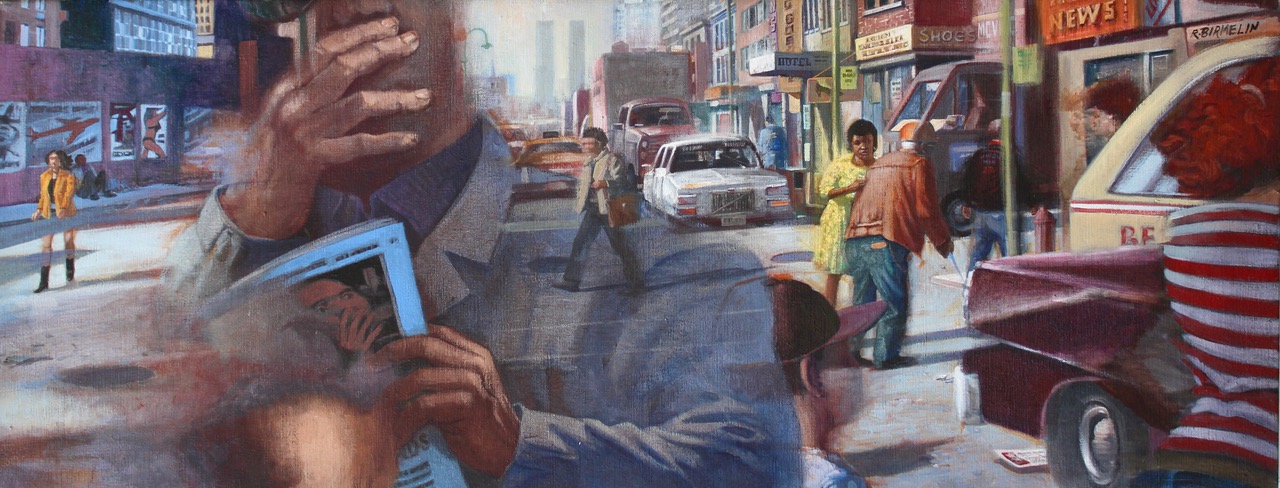

The renowned painter, printmaker, and draughtsman Robert Birmelin may be best known for his paintings and drawings capturing the movement and tensions of the urban crowd. He has also explored a range of other subjects, including landscapes and recently, memory and time. He often employs double imagery and creates reversible compositions that can be viewed from more than one orientation. Whether of an urban crowd or a Maine beach or domestic interior, Birmelin’s work often carries an air of menace, ambiguity, disjuncture. He manipulates the picture-as-window to show hyperrealist details, cropped figures, multiple viewpoints, and odd juxtapositions. All are observed details of our world yet ones that, reconfigured by the artist, take on extrasensory significance.

In an essay about drawing from 1963 Birmelin quoted Paracelsus. “The alchemist Paracelsus said, ‘If you wish to get hold of the invisible you must penetrate as deeply as possible into the visible… The artist can sometimes grasp certain essential relationships within a visual situation and so arrive at a vision of the ‘invisible’.” Birmelin’s work gives you just such a sense: that in deeply penetrating the visible, he evokes underlying dramas, journeys, fantasies, and dreams. His work depicts the hallucinatory and unsettling world we inhabit though may not always see that we do (until we view one of his compositions).

Since 2016, when Birmelin lost nearly all vision in his left eye due to macular degeneration, he has focused on drawing rather than painting. He’s produced several long horizontal narrative works, inspired by the format of Chinese and Japanese scrolls he has studied at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His exhibition history is long and distinguished. Most recently, his work was included in a group exhibition titled Good and Bad Government at the Clemente Center in New York (April–May 2021).

During the COVID shutdown, Birmelin began working at home. He has since moved out of his Manhattan studio, which he’d maintained for over 35 years, first on 125th Street, then on West 14th Street and finally on West 39th. Earlier this summer I met Birmelin at his home studio in Leonia, New Jersey, just a few minutes’ drive from Manhattan. It was once the studio of American artist Enos B. Comstock. Lit by two magnificent north-facing windows, filled with paintings from his six-plus decades of work, the better part of a wall is pinned up with Birmelin’s most recent work. He calls these his “investigations”: intricate pen drawings, many of which are touched by watercolor washes.

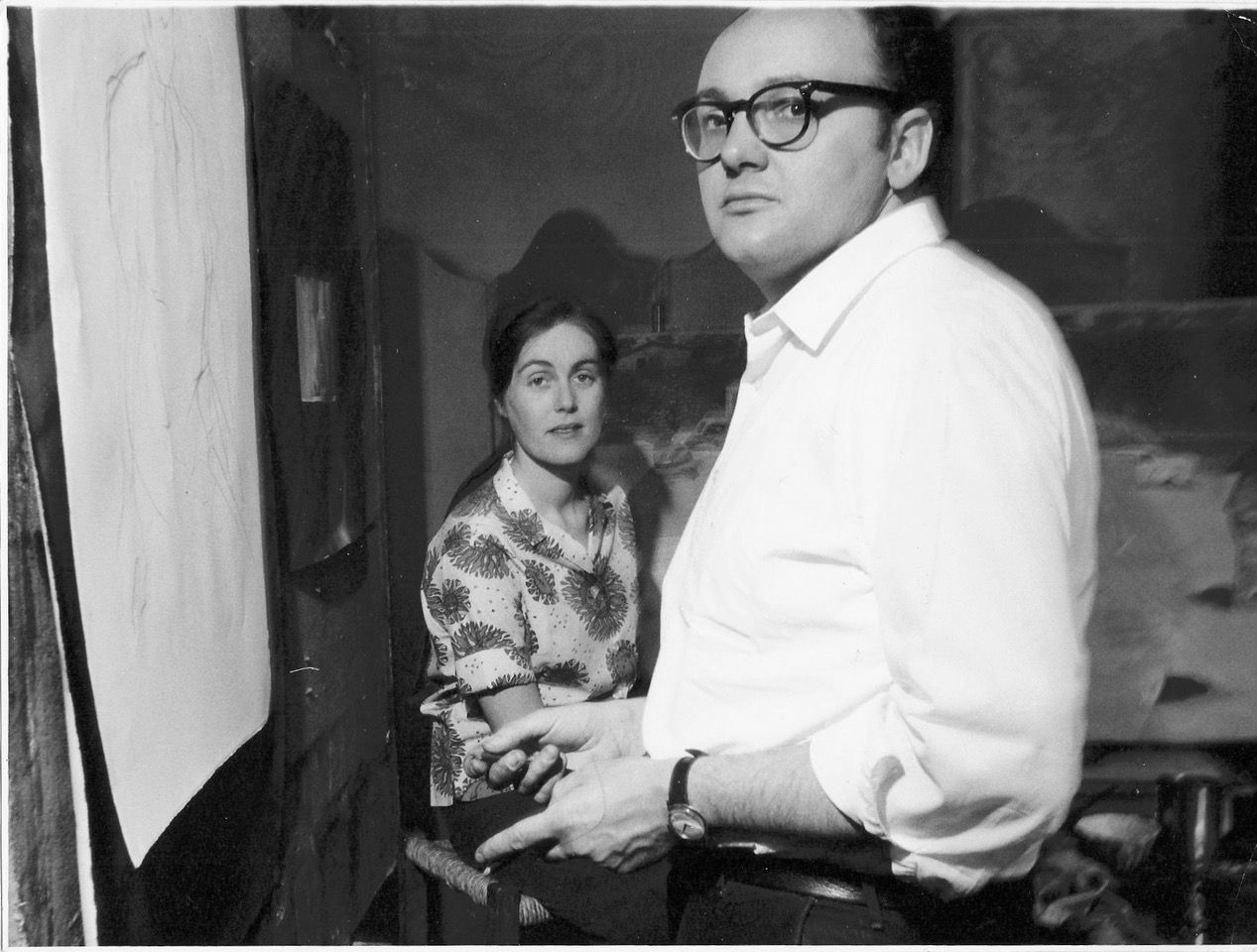

Birmelin was eager to show off some of his recent work. He made much of it in the last two years, a period of concentrated loss for him when his wife of 60 years, the artist and novelist Blair Birmelin, died.

Over the course of our visit, Birmelin talked about many things: about his studies at some of the most prominent art schools in America, the ways in which his work has evolved over the years, and how his vision loss has affected his sight and work. He’s an artist who has always had a personal vision and commitment to observation. Also one for whom everything always seems to have fallen in place.

Birmelin’s first meeting with Josef Albers and admission to the Yale Art School

With the encouragement of a teacher at Bloomfield High School, Birmelin applied and was admitted to the Cooper Union Art School, which he attended from 1951 to 1954. He then attended the Yale Art School from 1954 to 1956, receiving his BFA.

Josef Albers, the recently been appointed director of the Yale Art School, was actively recruiting for Yale. Birmelin and several other students from the Cooper Union had been invited to campus to show him their work. Birmelin still has a vivid memory of meeting Albers for the first time:

“We were ushered into an empty room and told to stand against the wall and put our work on the floor in front of us.

Josef Albers comes in, a short stocky man wearing a gray flannel suit and yellow tie. He looks around the room. And then he says—with a German accent, of course—“Well, who will speak first?” Everybody just stands there. No reaction. Then he points at me and says, “You boy.” The work I had brought was very much influenced by abstract expressionism. I’d brought a few figurative things, prints, but mostly had a lot of drippy gestural paintings and drawings. I started to say something. He cut me off immediately and went into a spiel about these drips, disgusting drips, New York drips, how they’re shit, and so forth, and so on. Here I am, this 18-year-old kid. I’m demolished. Right? Absolutely demolished.

He goes around to the other people, essentially saying similar things. And then he looks around the room again, and points to a few of us: “You, you, you, you. Go next door.” Four of us had been chosen. We went next door, where the secretary, Mrs. Clancy, took our names and said, “Come back in September.” That was it. We were admitted.”

Finding a mentor and friend in painter and draughtsman Bernard Chaet

Once at Yale, Birmelin and Albers did not see eye-to-eye. As a result, he avoided the classes in painting and instead gravitated toward Bernard Chaet, a painter and masterful draughtsman who taught drawing. Chaet became Birmelin’s mentor and friend:

“Bernard Chaet had a great interest in old master drawings and taught a very rigorous course. He wrote a couple of books on drawing, one of which is the best book on drawing I’ve ever seen.

We did observational drawing in his course, with a lot of reference to old master drawing And careful observing of volumes and how they were shaped in depth. The drawings I had done at Cooper Union were very much within the abstract expressionist orbit, they were very loose. At Yale, I learned how to be much more precise, how to observe better, how to modulate a line to create a space. Because I was having difficulty with the painting, it was a great encouragement to study drawing with Chaet. The painting at Yale at that time was largely abstract, which I was moving away from. Constant observational drawing was cleansing my practice.”

Along with drawing “ferociously,” as Birmelin says, he began to make etchings, which led to what he considers his first “independent” work:

I wrote a formal thesis for graduation and made a series of prints, which were most often done sitting up late in the middle of the night. I got a good response from Bernard Chaet and printmaker Gabor Peterdi, not so much from Albers.

He continued painting, though not at school but in an apartment he shared with two other students.

“I was painting in monochrome. At the time I was very influenced by Dutch still life painting. I wouldn’t call it magical realism—but a very high focus painting in near monochrome. I was timid about bringing in those paintings to the school because it was so out of line with the work that was happening there.

Albers’ major focus was on color and the modernist tradition. To be fair, he was a brilliant, if idiosyncratic teacher with a broad background in European modernism and culture. He was open to inviting artists who were bringing differing perspectives. Willem de Kooning, James Brooks, Corrado Marca-Relli and others were invited as visiting critics, for example.

But of course, the center of Albers’s practice and theoretical interest was color.”

An unforgettable lesson in painting from Edwin Dickinson at the Art Students League

After graduating from Yale in 1956 , Birmelin was living at home in Bloomfield, New Jersey, somewhat adrift. He got a draft notice. Before leaving for a two-year stint in the Army, he spent a several months in Edwin Dickinson’s class at the Art Students League, painting from the figure under natural light. He’d not done any painting from live models while at Yale but had become intrigued by Dickinson’s work—and interested in studying with him—when he’d seen it in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

“I painted with Dickinson for a couple months. It was a very important experience. He didn’t work from a graphic start, but from patches of color, which somehow coalesced eventually into a representational image of remarkable accuracy.

At first, I made a fresh painting every single day. And then I extended it to making a painting that would last two days, and try to get it further into it. It was the fall of the year, then into the winter, the light became quite dim in the afternoon. So, by 4:00 or 5:00, with only natural light, the shadows deepened. Dickinson would come around, not that often, and wouldn’t say much. He was very concerned with tonal relationships. One day I was working on a painting. He looked at it a while, then he put his thumb on my pallet and mixed up something that looked like mud. He then said, ‘No, no. No, no. That tone is more like this.’ He rubbed the ‘mud” on the canvas. And that patch of paint, suddenly, became a luminous shadow tone.”

Birmelin served two years in the Army. When he got out, he returned to Yale. By that time, Albers had retired and Bernard Chaet was head of the art department. Though Birmelin was officially working toward an MFA in painting, he focused mainly on drawing and printmaking.

In his last year at Yale, Birmelin did some very large—six-foot, seven-foot—black-and-white drawings, which were part of his presentation at the end of his studies. At the invitation of Chaet, Eleanor Ward was visiting the art school. During her tour she viewed Birmelin’s drawings. Ward directed the Stable Gallery, an important contemporary gallery of the time, exhibiting work by Joseph Cornell, Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, among others. Ward admired Birmelin’s drawings and invited him to show his work at Stable in the fall of 1960. However, the drawings he had done had been made on cheap photographic background paper, which ripped easily. When the Yale presentation came down, he tore up the drawings that had captured Ward’s attention. That summer, he painted 14 large black-and-white paintings for Stable, based on the drawings he’d destroyed.

A Fulbright year in London

He never saw his exhibition, though. Just prior to graduating with his MFA, he received a Fulbright to London. Ostensibly he was going there to study William Blake’s prints, and was assigned to the Slade School at the University of London. He and his newly married wife, Blair, whom he’d met while studying for his MFA, set off on a Transatlantic liner.

Now, he sees missing that first New York exhibition as being emblematic of something that would play out for the rest of his career. He wasn’t always as good at promoting himself as he was at making art:

“I always thought how stupid, how naive I was. This was a big show, at what was one of the most important galleries in the city. I would’ve met many people. I would have made connections.”

His year in England was crucial to his growth as an artist. But his time at the Slade itself ended up being rather inconsequential. As he explains:

“They had three models posed at different places in a large, frigid room. The students were pretty much left on their own. They would be drawing and periodically the instructors in white smocks would come around very quietly and sometimes point out something. And those poor models. It was cold. They’d have a little electric heater by the side, but they were often blue from cold. One model was supposed to hold a pose for a week, another model for an hour, and a third did short poses. I was appalled by the way people were drawing. I drew there for a while but then I forgot about it. I briefly went to their painting room. But it was what I was seeing, the art in the museums and the galleries, that was important to me.”

Having gotten some distance from Yale and Albers’s influence, Birmelin began to teach himself to paint on his own terms. He set up in the apartment he was renting in a Georgian row house in Bloomsbury, down the street from what had been the London home (and now museum) of Charles Dickens.

“I wanted to be free of the inhibitions about painting that I had developed at Yale and about color harmonies and so forth and so on. In a sense—it sounds so stupid—to just paint things the colors as they were before me, as they were given.”

During the Fulbright year, he visited art museums in the Netherlands, France, and Spain. He was very affected by Spanish painting, especially Goya’s work; by Bellini’s Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr; Holbein’s The Ambassadors; the work of Fernand Léger from the early 1920s; and Balthus’s huge canvas, The Dream, which he saw in Paris. Daumier’s drawings and the work of Edvard Munch had a special impact, as well.

“Rome was a dream”

In the spring of 1961, Birmelin was invited to Paris to interview for a Rome Prize with then director of the American Academy, Richard Kimble. Birmelin was awarded a fellowship to the academy. He and his wife, Blair, arrived in Rome in September 1961. His fellowship was eventually extended for three years until 1964.

“I got the studio that Lennart Anderson had just vacated. The American Academy was designed by Charles Follen McKim [of McKim, Mead, and White] at the beginning of the twentieth century at the period of the American Renaissance style in architecture and the decorative arts. There was a wonderful big sculpture studio, and a huge painting studio really designed for someone who did murals. Huge skylight on the second floor with a balcony. It was a dream.”

While Birmelin was in Italy, history was unfolding in dramatic fashion in the United States. There was the Cuban Missile Crisis, John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the mass marches of the Civil Rights Movement. What Birmelin calls “big stuff” that made him want to return to the United States.

At the time, art departments throughout the country were expanding and Birmelin was invited to teach in several different programs. Both he and his wife, who was a printmaker and writer, wanted to be in New York. So he accepted an offer from Queens College. He was to remain on the faculty for more than thirty years. In addition, he lectured at other colleges and art schools as a visiting critic. He summered on Deer Isle, Maine, raised a family, painted and had many exhibitions. He occasionally earned enough money from his art to take time off from teaching.

While always distinctly his own style, Birmelin’s work has gone through distinct stages

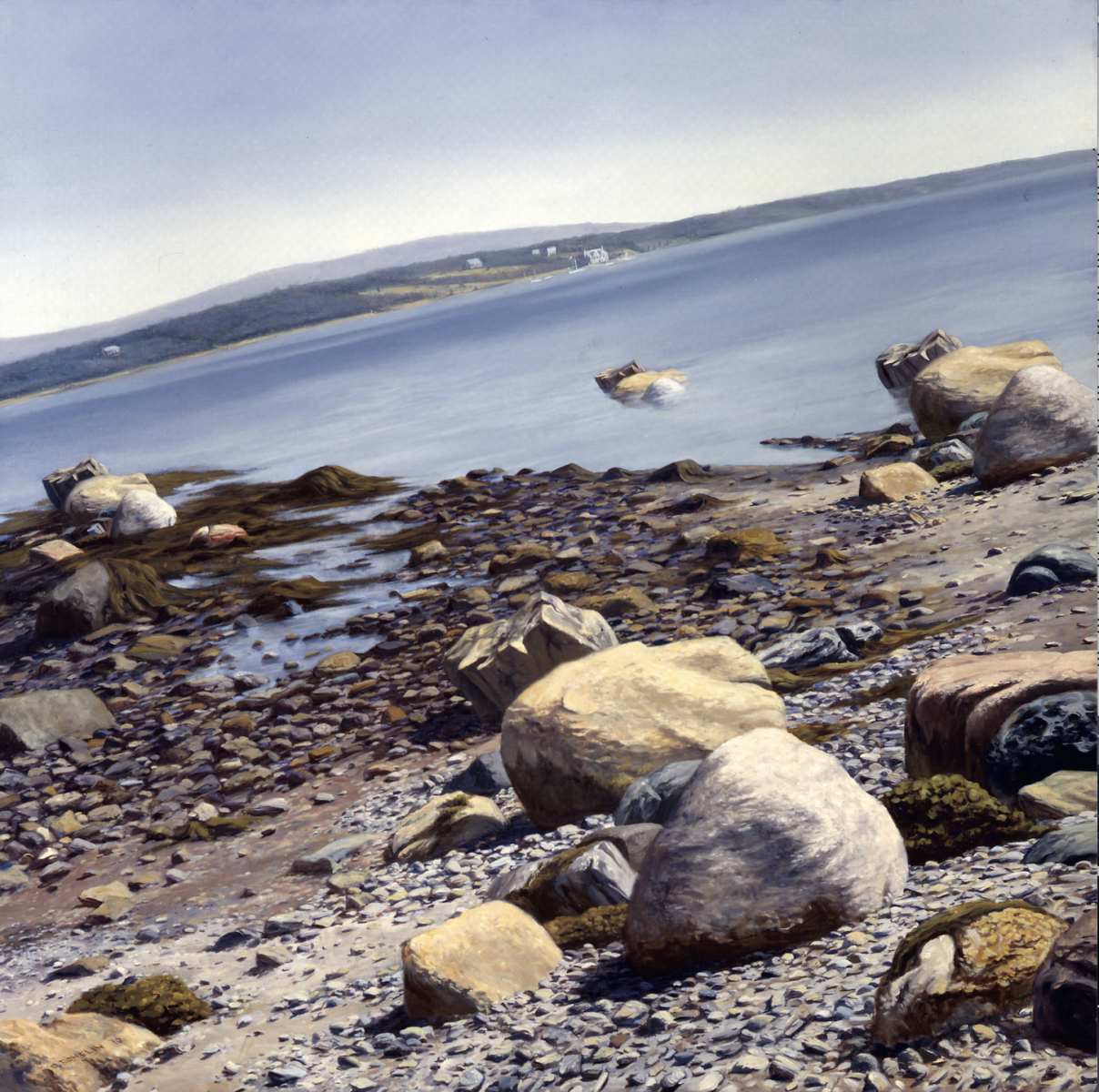

Over the decades, his work has evolved and gone through many distinct stages. For example, during several his summers on Deer Isle he painted landscapes.

“I sought to ‘purify’ my practice by painting outdoors on the Maine shore. By being attentive to the light, to the unique character of place. At the same time, I wanted to paint figures, and I couldn’t. I found myself thinking of the rock groups on the shore as families. Groups of mamas, papas, et cetera. Observing the way they were configured in the space eventually provided me clues as to how I could orchestrate figures. This led to the first ‘city crowd’ paintings.”

In the 1980s, he had what he calls a “good run”. The French art dealer Claude Bernard bought several of his paintings and showed Birmelin’s work at his galleries both in Paris and New York. At that time, he was making his renowned city crowd paintings. Critic John Yau wrote about these paintings in a 1983 essay for Artforum, saying of them:

“[Birmelin’s] method of presenting internal sightlines parallels the tradition of street photography. His paintings, too, are more than recapitulations. They are carefully composed, imaginative amalgams of moments anyone might experience while going from one place to another. Like his other paintings, The Street—A Gesture from a Stranger is an intensely realized field of vision, horizontal in format and with numerous focal points. One is reminded of the constantly roving eye that has to take everything into account, and the never-ending adjustments of instinct, pace, and direction, needed to thread one’s way through a crowd. At the same time Birmelin reveals the ambiguity of gestures: how nothing we see might be what it seems.”

John Yau

Reversible compostions

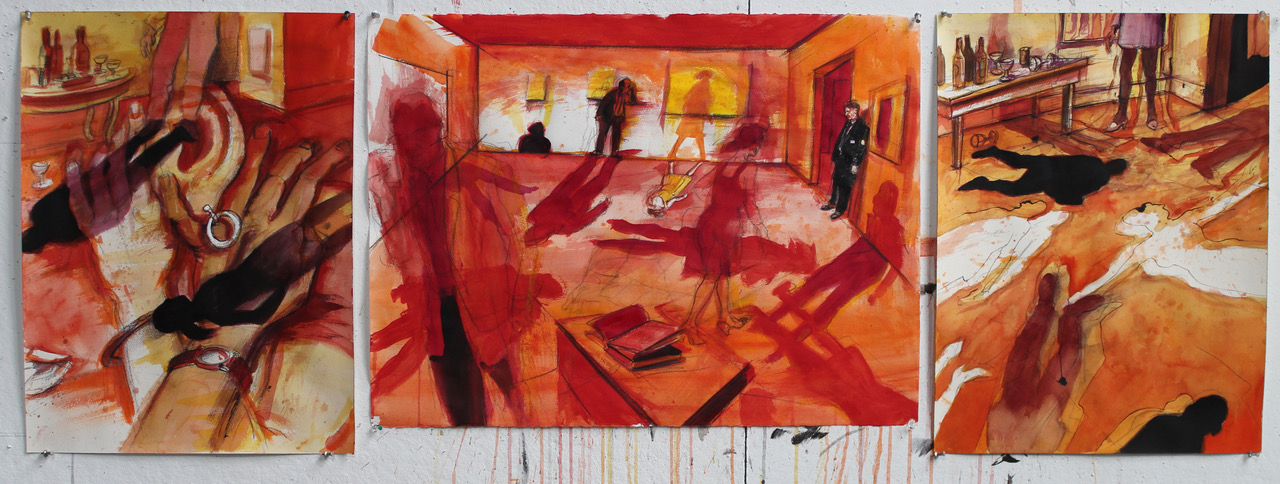

Birmelin began reconsidering this work when he had a heart attack in 1993. He started to focus more on “reversible” compositions—paintings that included multiple narratives and could be viewed from different orientations. Depending on the orientation, the dominant motif would change. As he explains:

“I felt puzzled about how to go further with what I’ll call city pictures. Also, when I was recovering from my heart attack, I began to think about things—my earlier life, my parents, my marriage. The paintings, which are reversible, came out of a couple sources. One was that when I talked with my sister about a family incident that had happened years earlier, when I was in my teens, I found she had a completely different memory of it than mine.”

“There’s also a short story by Dostoevsky about a man who does reprehensible things and knows so. But when he leaves his area of action and goes back home and sleeps and wakes, he feels he is a virtuous person.

This conversation with my sister made me think about memory and how fragile it is. What was the truth of the past? Of course, this is a question that historians struggle with all the time. The truth of the past changes with the era in which it’s written. Even though the attempt is to tell the truth, there’s a restlessness to truth. I started to make works which I wanted to be restless in that way.”

Engaged with what is happening in the world

A noticeable thing about Birmelin’s work is how engaged it is with what is happening in the world. He is a reader, and, despite his vision loss, is luckily still able to read with glasses in good light. Stacked on a shelf in his studio are books of poetry by William Butler Yeats and William Carlos Williams, Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others, a monograph on Michelangelo, a biography of Robert E. Lee.

He enjoys thinking about history and integrating it into his work. He’s done so most notably, perhaps, in a series of paintings and drawings called the “Uprising” series. Initially inspired by the uprisings in Egypt, the Middle East, and the Balkans in the early 2010s, this series now encompasses uprisings such as Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter. Certainly the “Uprising” series would also be relevant to the recent insurrection of January 6, 2021 at the United States Capitol.

Recent losses and its impact on his work

The most recent changes in Birmelin’s work come out of loss. His wife’s death has caused him to explore mortality. His limited vision due to macular degeneration has caused him to adapt the way he works.

“My wife died in March 2020. The work I did following her death was very much a reflection of that time. My work in general has very much come out of events in my life, though I sometimes didn’t recognize that at the time it was done. Most of the work I’ve done in the last two years has been in one way or another, however indirectly, related to my wife’s death, the COVID pandemic, and the loss of friends—-mortality.”

“In less than bright light I can hardly discern your features”

Birmelin has had macular degeneration since 2016. He has no remaining central vision in his left eye. As a result, when he looks at my face with his left eye, he only sees my hands in his peripheral vision. He consequently relies almost entirely on his less compromised right eye to see:

“My right eye is slightly affected by macular degeneration, as well. In low light I’m aware of a dead spot. Whether this is the macular degeneration or something else, I’m not sure. Also, there’s a kind of very, very slight… I can’t call it a fog across values and color. If I want to see color better, I make a ‘peek hole’ with my thumb and my forefinger and peer through it. This limits the amount of peripheral light coming in. In less than bright light I hardly can discern your features, but I can see the leaves outside the window very clearly. A late development is that I find that straight lines have begun to ‘wiggle’.

If I’m in a doctor’s office, with overhead light, everything has a slight film across it. If I look at this painting here, the dark tones tend to meld. Some of them, I can’t even see where they begin and end. The sharp contrasts are more visible.”

He’s found it harder to paint in larger scale in acrylics and, since 2017, has had to abandon several paintings he started. He’s now relying more on drawing. In doing so, he’s returning to a mode of artistic expression that was crucial to him when he was just starting off as a young artist and was using drawing, as he wrote in 1963, to “make contact with the nature of things:”

“Painting with my vision this way is more difficult. I have tried to work on a couple small canvasses and, though I can’t say I’m seeing it blurring, I’m not seeing it well. That’s why most of my work in the last couple years has been graphic. With a pen—the black, white contrast—I can see, I can draw. I also use watercolor with a basic a linear underpinning, but I use very limited color.”

Since 2021, Birmelin has been working on making scrolls and books, among other things. He pieces together individual drawings and paintings to create lyrical narratives, which he then has printed in small editions. Depending on whether the printed material is folded or rolled, the story unfurls as the scroll is unrolled or the pages are turned. Chinese scrolls at the Met inspired him to do these works:

“One of the scrolls at the Met was of a journey. A young man goes in search of his parents—through the mountains and across the river and through the town and so forth. I stayed so long, looking at that, following the journey, realizing there is a cinematic aspect but unlike cinema, you can go either way, you can recap, view from varying distance and can compare parts in a way a film does not allow.”

An Ordinary Day

One of his scrolls is called An Ordinary Day. He unrolled it for me, as he had several others the afternoon I visited. The visual panels draw you, the observer, in as the main character experiencing just that, an ordinary day. Waking up, having a cup of coffee, going out on the street, ducking into the subway. Passing people, like a figure that appears in one of the frames and becomes the central focus. “Is he going to work, or is he unemployed? Is he picking stuff up off the ground or is he going busily about his business?” Birmelin said as he walked me through the day. “You move along the street, notice the sidewalk. You’ve gone somewhere, time has passed, and you’re out onto the street again. Lights are on. Night comes. In the final frame, amid the darkness, there’s a dream.”

Indeed, Robert Birmelin’s works leads us there over and over again: to a world which is a weaving of reality and dream.

We’ve posted additional reproductions of Birmelin’s work on his artist page.

Comments

The superb presentation in images and text left me with a question……..

I googled in curiosity of who the internet would report as the world’s finest living artist. The answer should have been Robert Birmelin.

The Wheel of Fortune has to spin around a few more times.

An excellent history! I’ve spoken often with Birmelin and written about his work but found many new facts and stories here. Thanks.

Valuable account of a productive creative life and the sources of Birmelin’s wonderful images.

This is a well documented and fitting tribute to a unique artist. Thank you

A great article on an artistic giant; Robert Birmelin is an American treasure.

She did an excellent job presenting you and your wonderful work…and of your intense need and love to draw despite the macula.

Especially loved the 1963 photo of you and Blair.

O am very appreciative of this insightful view of Birmelin’s artistry and life. It was a supeeb analysis of his talent — a weaving of his intellectual curiosity, experiences and his remarkable art.

I agree with you all.

I’ve reminded Bob many times that there is no “fair” in our art world.

However, I believe that eventually, in the end, the cream always floats to the top.

In the meantime, as T. S. Eliot said: “for us there is just the doing, the rest is not our business.”

In the 80’s when I was in the MFA program at Brooklyn College, I became aware of Mr Birmelin’s paintings and drawings. His work is so rich in so many ways it was overwhelming and inspiring. I am still blown away by his creativity, his process of folding imagination and observation which is married into his imagery. What a great painter! How under appreciated he is! I wish the Whitney would host a major exhibition of his work!

Leave a Comment