A studio Visit with Master Artist and Illustrator Robert Andrew Parker

August 14, 2014

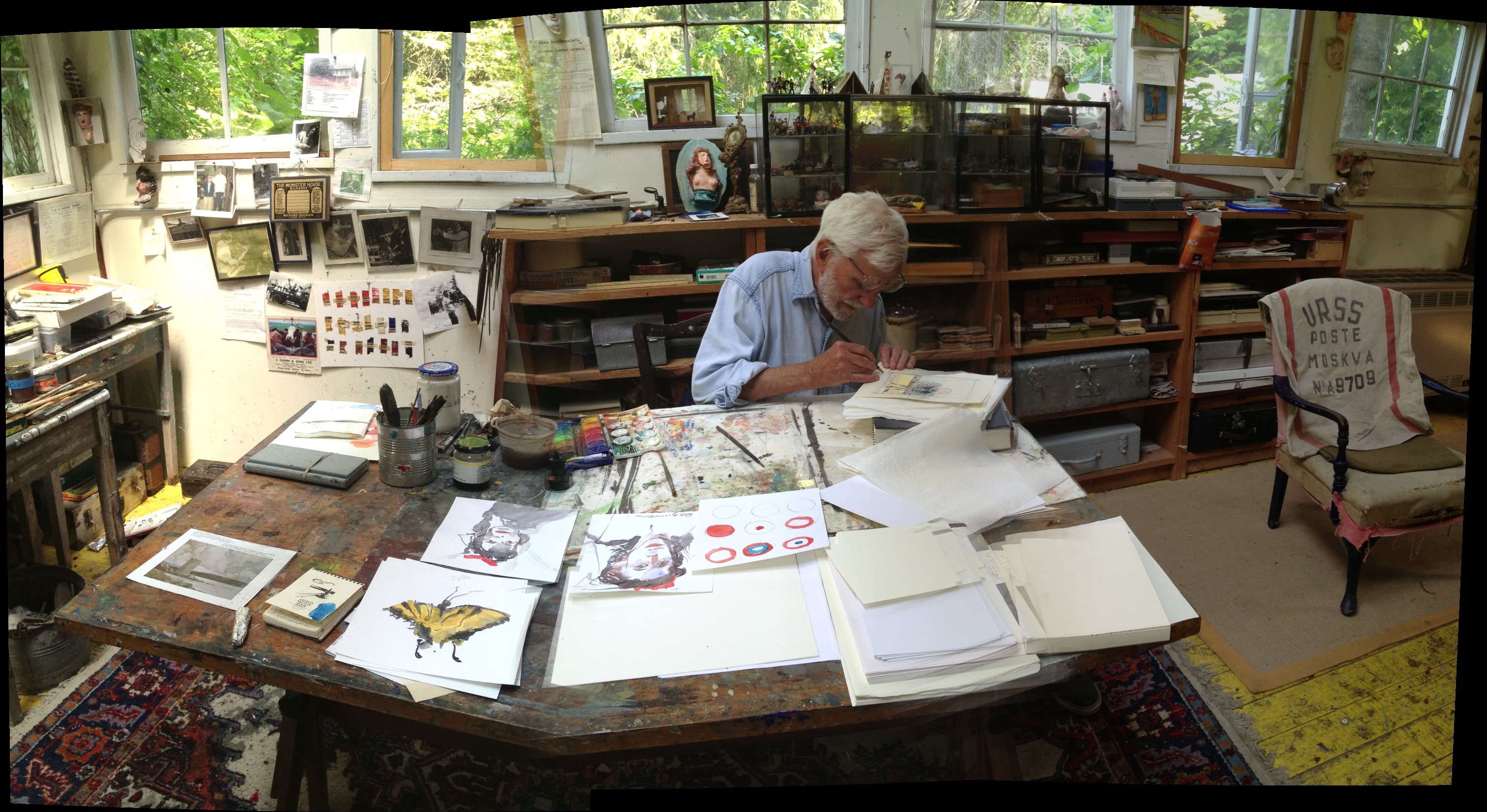

We visited the artist Robert Andrew Parker in his studio the summer of 2014, after seeing an unforgettable retrospective of his work at the Century Association in New York.

Robert Andrew Parker may not be a household name the way Rembrandt is, but his artwork is in the collections of many major museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MoMA and the Morgan Library & Museum. His drawings have appeared in magazines such as The New Yorker and Life magazine. He’s illustrated more than 100 books and has received prestigious grants.

Now 87 years old, he’s spent more than half a century drawing, painting, illustrating, and making prints. A dizzying selection of that work was recently on display in July of this year (2014) at the Century Association in New York.

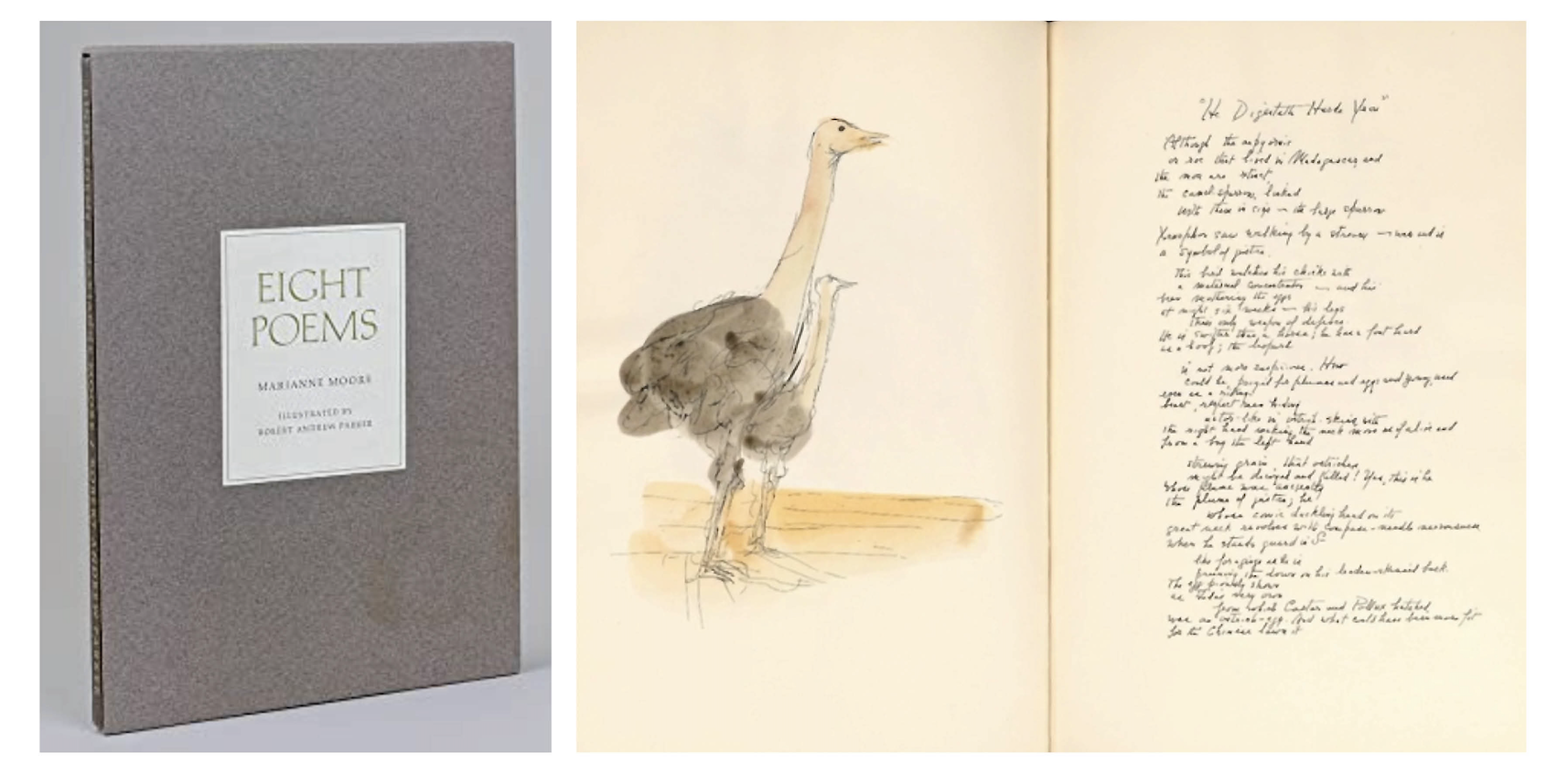

An “accurate and at the same time most uniliteral of painters”

The exhibit was bookmarked by work from very early in Parker’s career, when the poet Marianne Moore saw some of his art in the 1950s at MoMA and wrote an essay lauding him as “one of the most accurate and at the same time most unliteral of painters . . . [a painter who] combines the mystical and the actual, working both in an abstract and a realistic way.” On the other end was Parker’s most recent work, which has been done under conditions of vision loss, yet remains, as Moore put it, both uniquely “accurate” and “unliteral” —by which we think she must have meant unmistakably filtered through Parker’s unique consciousness.

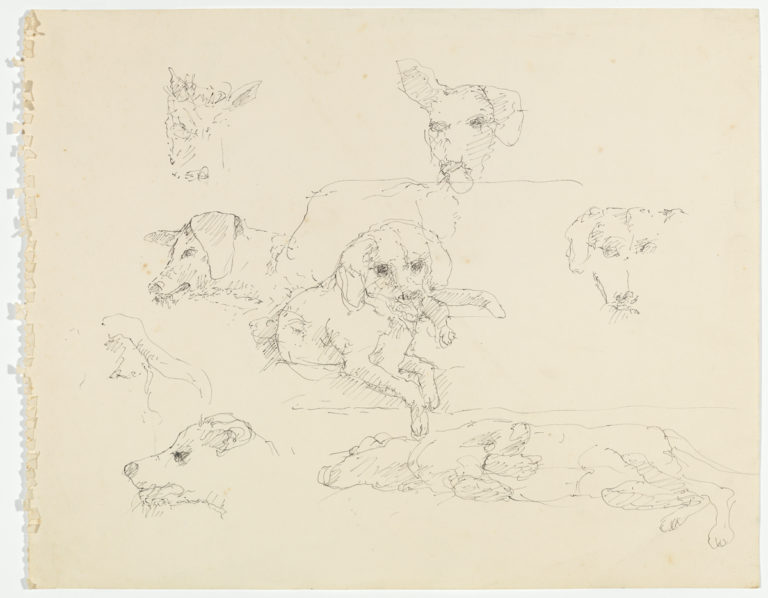

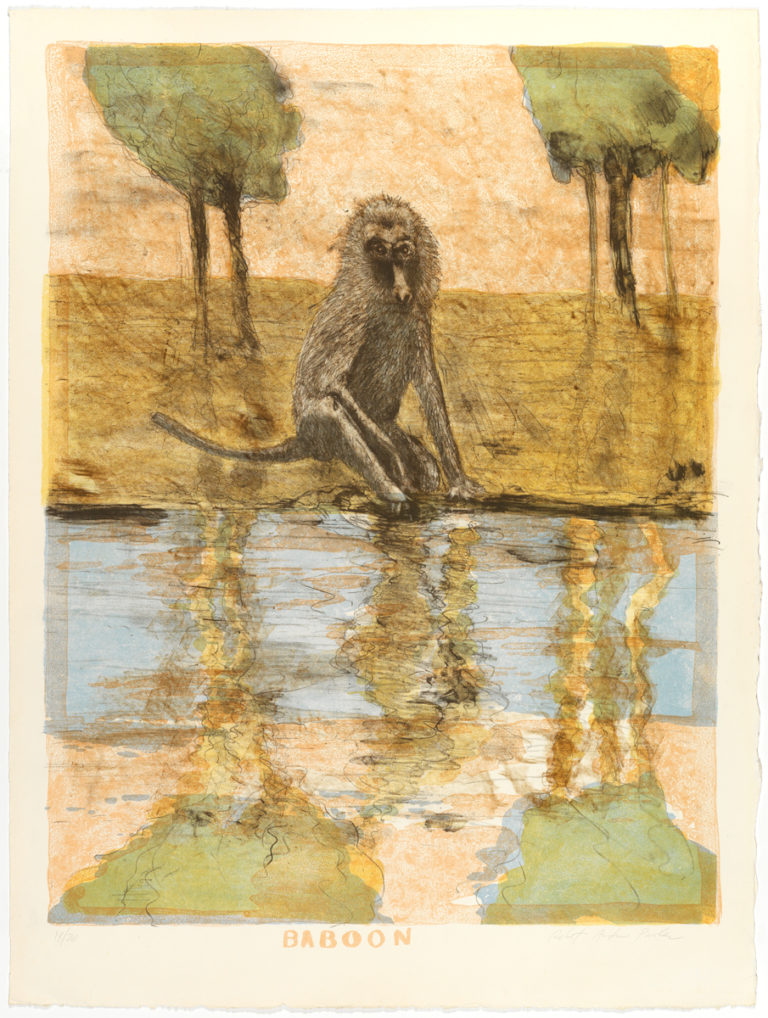

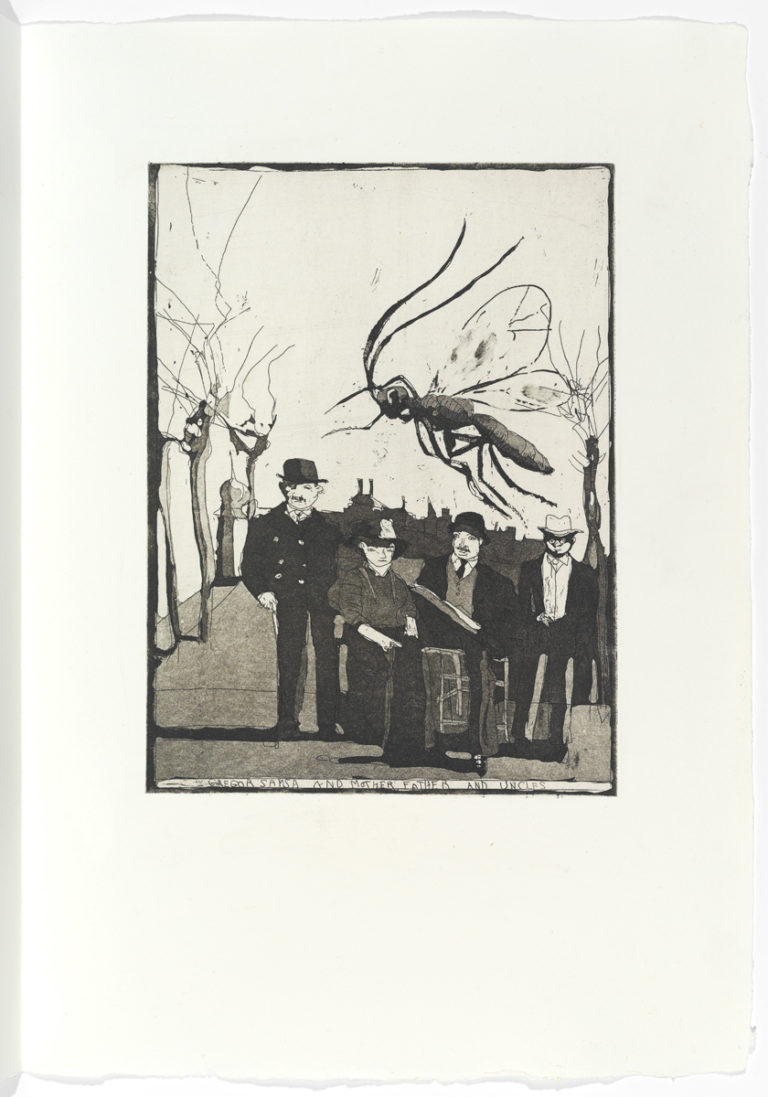

As the retrospective exhibition made clear, many of Moore’s observations about Parker, made at the beginning of his career, still ring true. His subjects still include, as she noted, “animals, persons—individually and en masse; trees, isolated and thickset; architecture, ships, troops.” His “proficiencies” too still “range wide,” with formidable technical skills in the areas of printmaking, monotype, drawing, watercolor, and oil. And perhaps it is what Moore characterized as the “depth and stature unvitiated by egotism” in Parker’s work that accounted for its force of mood—from the elegiac call of his landscape to the disturbing thrum of captive monkeys and decadent Nazis.

Art was one of the few things not affected by vision loss

After viewing the exhibition, we visited Parker in his West Cornwall, Connecticut studio. As we pulled up the gravel drive to the right of his modest farmhouse, we saw Parker waiting for us on the porch, a book tucked under his arm. Immediately familiar and welcoming, he was a gracious host and, as we would learn during our visit, a gifted raconteur and man of letters.

Though he’s had macular degeneration since 2000, no vision or age-related struggles were evident as we walked with Parker to his studio, a converted freestanding barn behind his house. However, he said “almost everything” in his life has gradually changed over the years since his diagnosis. He spoke of feeling shaken the night before when his vision caused him to become disoriented while en route to a musical gig (he and four of his five sons are accomplished jazz drummers). He was afraid driving and reading would soon both become things of the past for him (as hiking, fishing and biking had already).

Pointing to the book under his arm, he joked that it was merely for show. Once a voracious reader, he now finds reading such a struggle that all he perseveres with is The New York Review of Books every other week—over which he pores, magnifying glass in hand—a daylong affair. He said it seemed the only thing that hadn’t been adversely affected by vision loss was his ability to make art.

A studio crammed with treasure

Under a flood of natural light, Parker’s studio appeared. It was crammed with treasure, a visual representation of his idiosyncratic interests and the landmarks of his life.

Lining one wall are shelves stuffed with books on history, art, travel, and medicine. Model airplanes hang from the rafters. His desk is stacked with paper and scattered with the accoutrements of his trade. On myriad surfaces are animal skeletons, busts, figurines, and miscellaneous trifles he’s found at the dump. His own works of art, as well as that by others, hang on the walls, along with photographs of family and friends in an array of places doing an array of things and glass cases of toy soldiers.

Parker’s most recent projects are placed prominently upon the various surfaces, while flat files contain hundreds of works on paper dating back to the early 1950s.

Opening the drawers of his flat files, which are sorted by subject matter, he leafed through prints and drawings of the visions he has spent his life exploring. In one drawer was the gravitas and grandeur of gray warships and bombers. In another, intimate depictions of nudes drawn from life. Yet others opened to stark and moody landscapes, portraits emphasizing his unique interpretation of the people who sat for him, insects and animals either lovingly rendered from life or carved into the paper to capture a sense of their captivity and strain. These are the subjects that Marianne Moore noted in 1959 as the artist’s preoccupations and are the ones to which he has returned time and again over more than six decades of work.

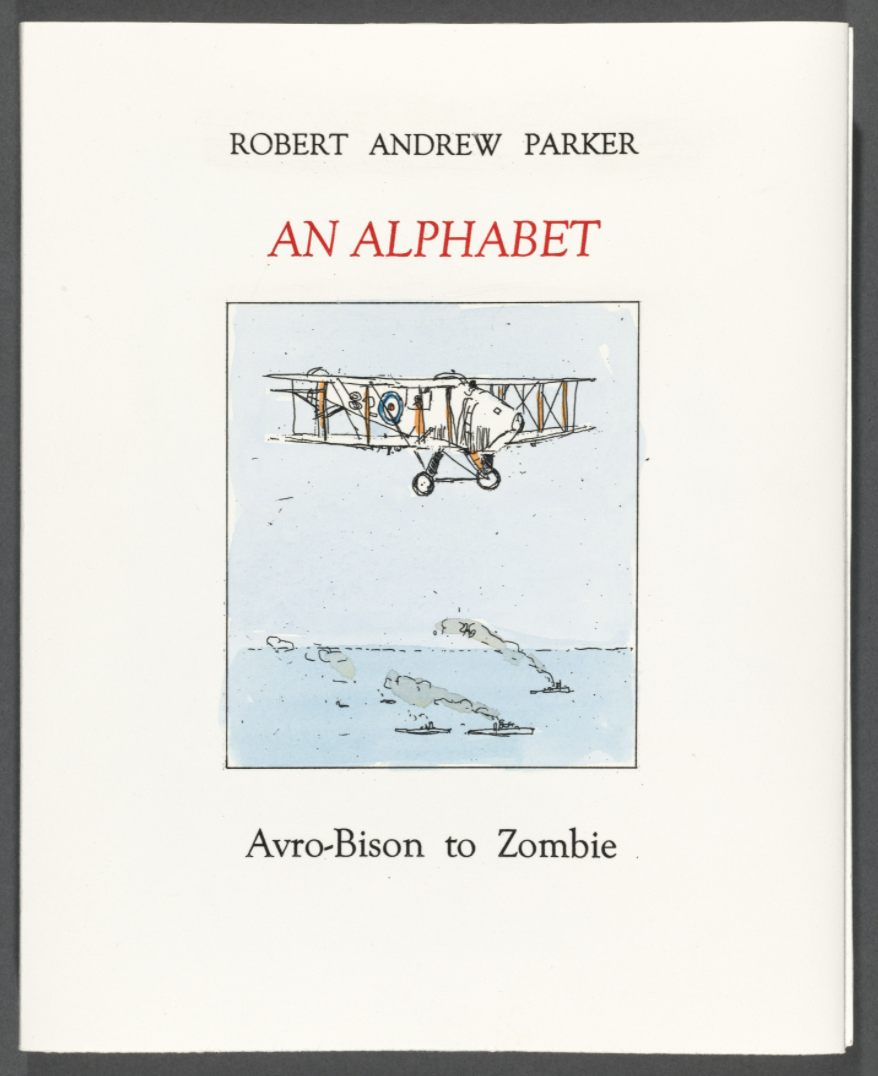

Old tomes and books

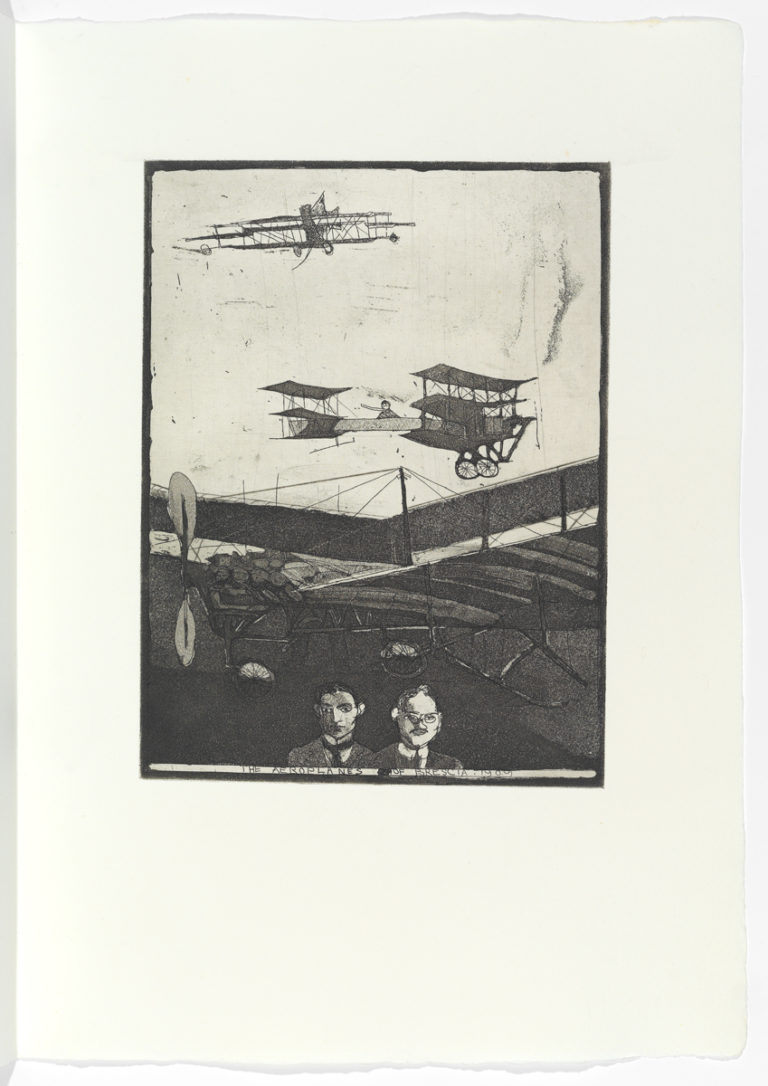

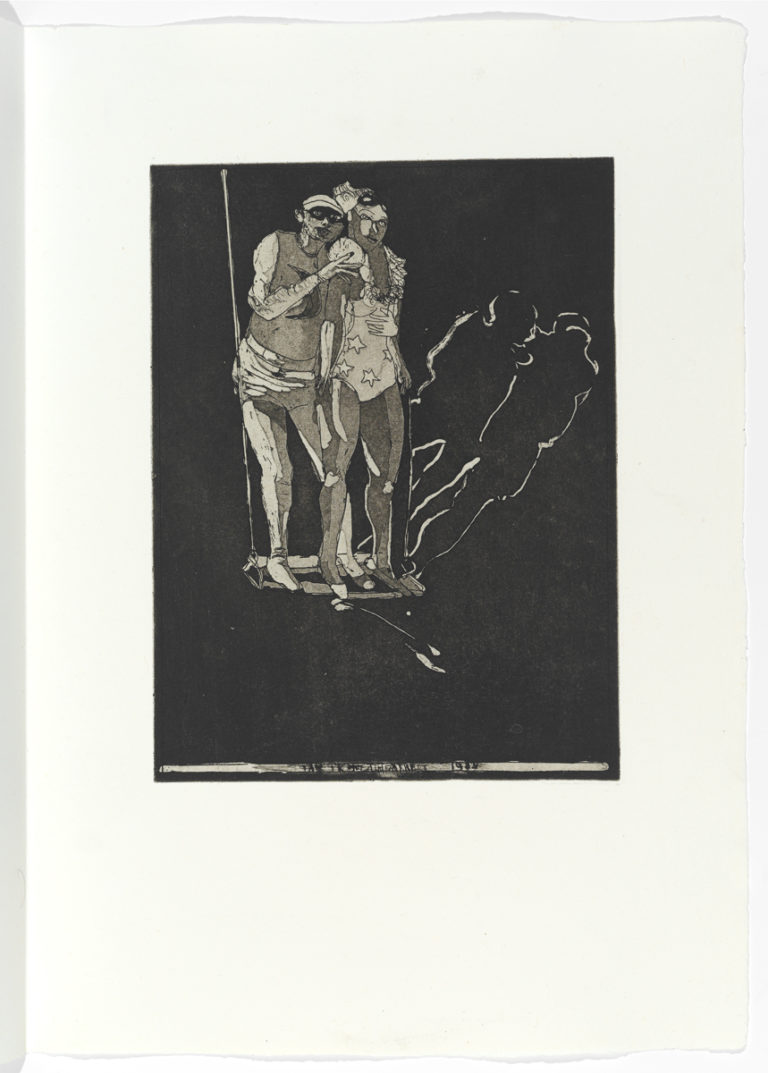

Old tomes and books, the kind you get at library sales or find in attics, were positioned on a table in the middle of his studio. Parker pulled one out and opened it. He’d in fact created a box of the book. It held 26 hand-colored etchings: An Alphabet, Avro-Bison to Zombie.

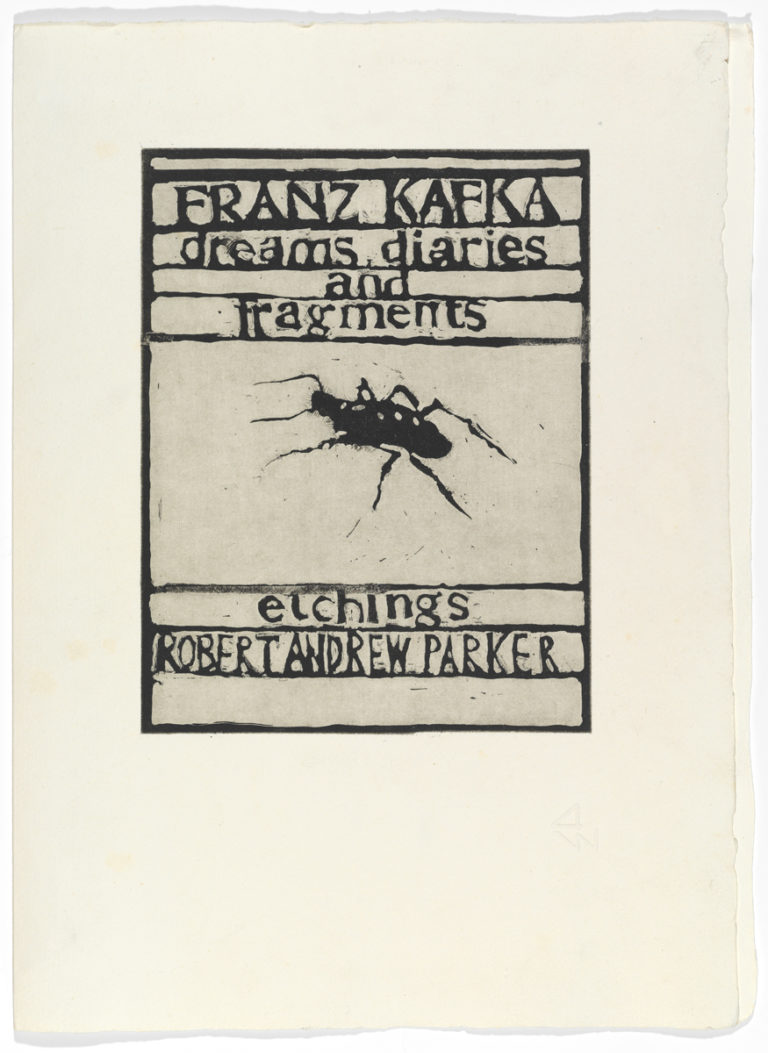

Each book on the table was filled with its own unique set of Parker’s handmade series and books in a variety of mediums—monotypes, intaglios, ink and watercolor, acrylic. There were different sets of alphabets, adventure stories, bawdy tales, Parker’s takes on literary classics (Randall Jarrell’s Death of the Ball Turret Gunner and Kafka’s Metamorphosis), and fanciful compilations of an astonishing range, such as one containing portraits of famous women authors, his wife tucked in between Dorothy Parker and Virginia Woolf.

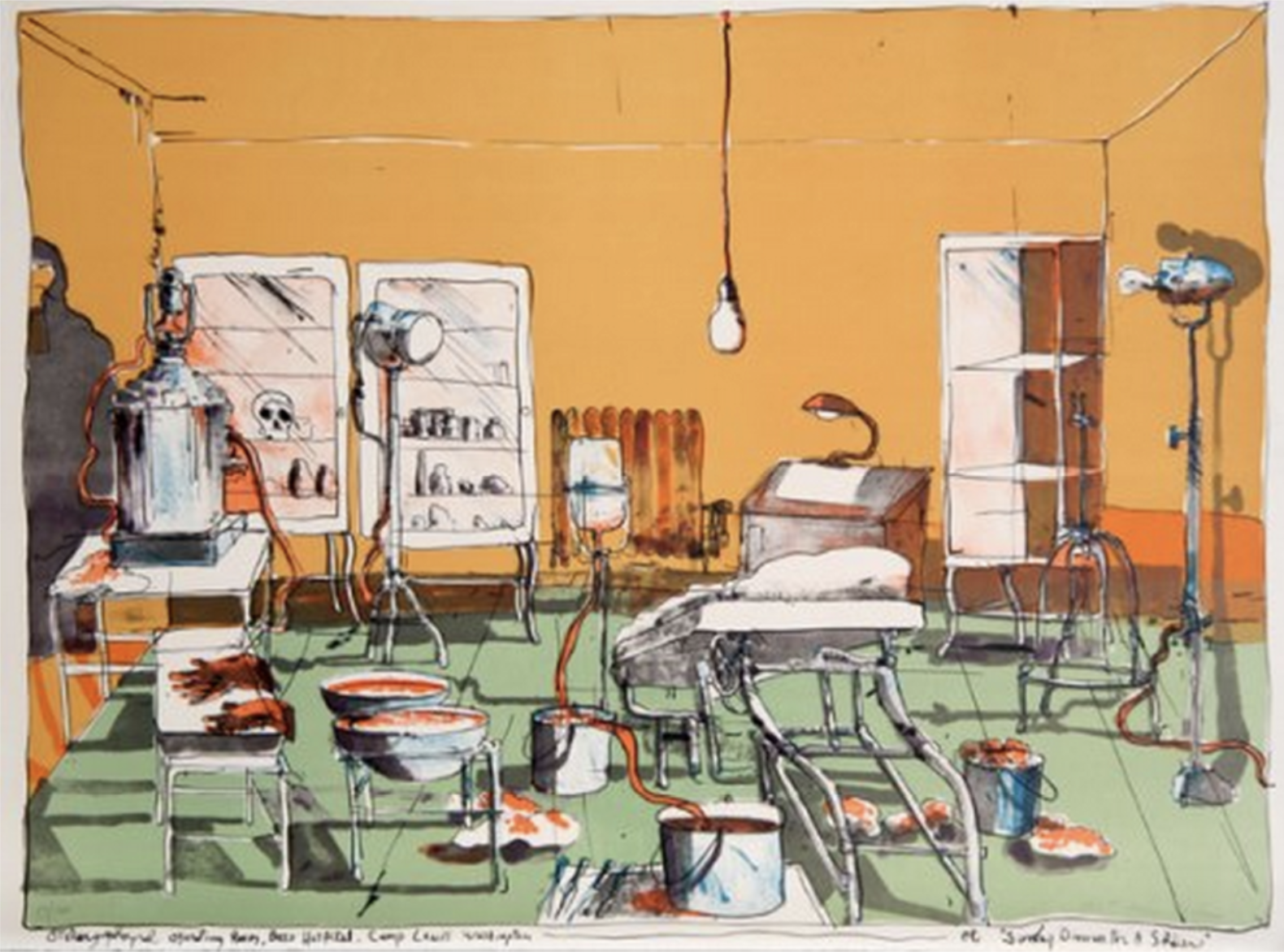

A master printmaker

Parker attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago after a term in the military during World War II. (He saw no conflict, but came away with a lifelong interest in B59s). Afterwards, he continued his studies at Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17 in New York City and has spent his life making prints.

He especially enjoys the process of intaglio printing, a technique he studied at Atelier 17 and of which he is, hands-down, a master. Though the subjects that appear in his prints also appear in his drawings and paintings, his prints can become more eccentric, imaginative and emotionally complex, as the works hidden in boxes illustrate.

In his lithograph Sunday Dinner for a Soldier, for example, Parker’s incisive politics and ethics are evident where a familiar leitmotif of his oeuvre—a preoccupation with war—confronts the viewer with a scene more brutally obvious than his paintings of planes and battleships: a bloody clutter of clinical instruments and viscera in a space befitting a coroner’s room. Parker tells us he is a pacifist who was active in the antiwar movement of the 1960s. Along with some of his other most disturbing work, he made Sunday Dinner for a Soldier in 1968, in urgent reaction to the carnage of war. (That same year, a picture of him participating in a Vietnam War protest appeared in The New York Times.)

Landscapes of a recent trip to the Midwest

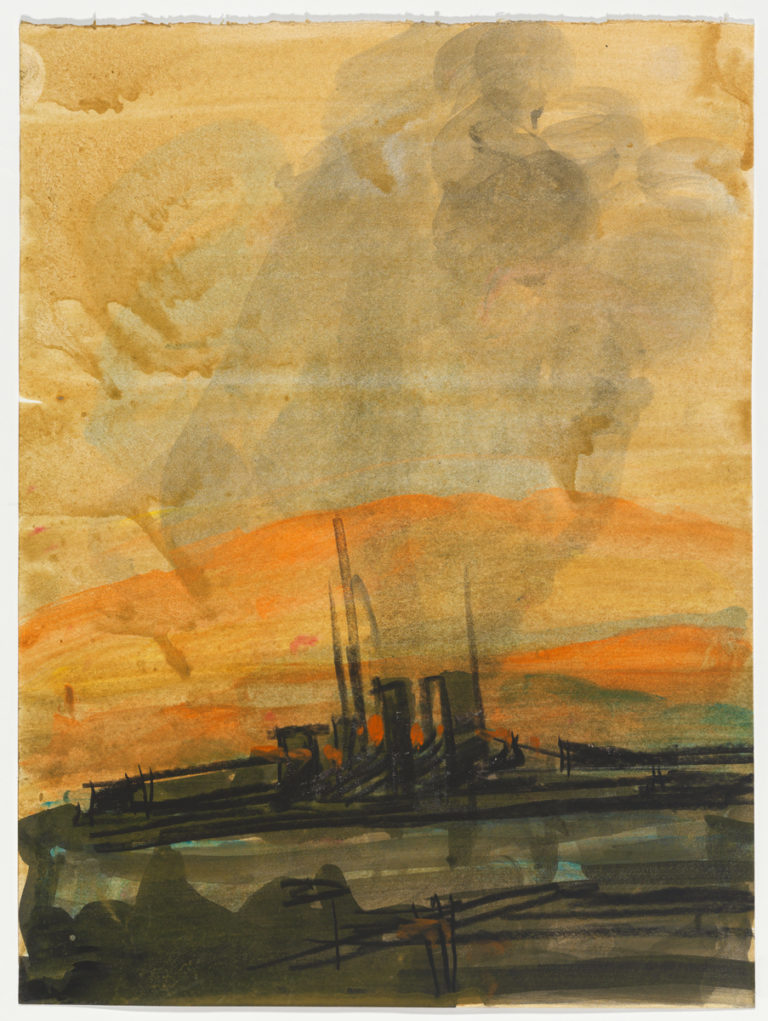

Parker’s more recent work includes watercolor landscapes of a trip to the Midwest he and his wife, Judy Mellecker, took earlier in the summer. With his wife behind the wheel, he was free to spend many days of idle time looking out the window and contemplating the stark landscape. He sometimes sketched as they drove.

Parker shows the same predilection for conveying accurate and evocative impressions of the world in conversation as he does in painting and drawing. As we went through his stack of Midwestern landscapes, he told us that one crop was prominent along the journey—rape (rapeseed) for days on end. Only a stray dog running along the highway here or there broke the monotony. Rape was a problematic crop, he explained, because humans don’t consume it. “Any kind of insect repellent” can thus be used on it. The pesticides continually deployed on the fields had entirely wiped out insects; hence, birds were absent. The farms and silos that had once populated the landscape were gone as well. So were the fences that had marked and organized space. This was because corporations planted and harvested the rape monoculture, then trucked it to “one vast silo somewhere to be pressed for oil.”

The landscape is depressing,” he said. “Not to mention the towns with, oh God . . . what’s that eating-place with the girl’s name on it? That’s inedible,” he grimaces. “Like ground cotton.”

Feelings and sentiments that demand attention

As his retrospective at the Century exhibit made clear, Parker is an artist who finds a great deal that is beautiful in the world, a great deal that is funny, a great deal that is tragic and disturbing.

As evidenced in the Midwestern landscapes, Parker’s feelings and sentiments about the world stare back at you and demand attention. Partly it’s his mark-making that is so expressive—what Moore called his “private calligraphy.” With a charcoal stub, he draws signature-like scrolls across the page and strikes it with furious lines, creating an almost audible statement, a soundtrack, that accompanies the moody pools of watercolor that call forth a field, golden. His color is as expressive as what Moore saw more than 50 years ago: “washes of clear color touched by some speck or splinter of paint—magenta or indigo—spreading just far enough.”

“Memorial Gardens”

Along with the subjects and mediums that have long fascinated Parker, he has recently begun constructing small dioramas of painted plaster busts. He just received a grant to cast them in bronze. Parker calls them his “Memorial Gardens.” Like his lithographs of captive baboons, or Soldier’s Lunch, these “Memorial Gardens,” which fill the gaps and cracks of his studio, are disturbing.

Heads and busts are nested within altar- or crypt-like enclosures together with an assemblage of idiosyncratic found parts and artifacts. The figural elements in most of these “Memorial Gardens” are misshapen or disfigured. As he pointed them out in rafters and corners, Parker said, “I never dreamed five or ten years ago that I’d have a room full of three-dimensional things.”

For an artist with diminishing eyesight to turn to sculpture is not an unfamiliar strategy, but Parker dismisses the notion that macular degeneration might be affecting his choice of media. Though it seems inimical to the complexities inherent in the “Memorial Gardens,” he credits their birth to a playful gesture he made one day: while considering a small graphite and oil figure study he’d done of a poet, he shaped a deftly seen head out of plaster and fashioned it onto the canvas, happy when The Poet in all his hubris came to life.

Parker is part tinkerer at heart

It is perhaps the very openness inherent in musical improvisation (he’s spent his life playing in jazz bands), born of a curious mind that willingly crosses over borders and associates freely, that compelled Parker to this leap of experimentation with plaster. He began with making bas-relief portraits, such as one of Virginia Woolf, delicately hand-painted with a plaid blanket pulled up to her chin. These then led to the “Memorial Gardens.” In these most recent pieces, he transmogrifies existing sculpture by covering and making a mold of it with plasticine, then twisting and shaping it, reassembling it, and filling the now unique and original mold with liquid plaster of paris. Once the oil clay is hardened, he strips it off his plaster cast and further transforms it through the application of various paints and paraphernalia.

As he talks of having taken the nose off one of his heads and turned it upside down, it becomes clear that his casting process is part invention and part experimentation. “It almost works,” he says. “Pretty interesting, right?”

The increasing prevalence of loss

Like many artists, Parker rarely comments on his own work. He does offer that his “Memorial Gardens” are not coincidental to the increasing prevalence of loss in his life. As time marches on and peers pass away, the “Memorial Gardens” become an avenue through which he explores mortality. They’re also an outlet for the found objects in his studio that have long awaited a resting place. But these “Memorial Gardens” are also homage to the life and work of Richard Dadd, he tells us, the late-19th-century English painter incarcerated at Bedlam for murdering his father. Dadd’s paintings have fascinated Parker since he was a child and first saw them reproduced in an issue of Time magazine. As a fully mature artist, he has begun to explore this fascination—enabled, perhaps, by the confidence that only age and accomplishment can bestow.

When it was time to go, we stood with Parker for a few minutes in the shade of the grape arbor he’d planted outside the door of his studio. He had already experimented with having several of his “Memorial Garden” busts cast in bronze at a foundry in Philadelphia, and they hung from hooks beside the door: ponderous and threatening, placed as if to keep watch over his studio. With a casual air he explained he’d put them there for the practical reason that they were fresh from the foundry, bright, and he wanted them to weather and form a patina.

Come winter

Casting the “Memorial Gardens” was one of several projects that would be occupying his attention in the coming months as summer waned and the cooler, shorter, darker days took hold.

He turned one of the heavy masses in his hand as he spoke to us. Painting the casted heads was going to be a challenge since—as with all metals—paint does not easily adhere to brass. Once they weathered sufficiently, he explained, he would buff and burnish them with steel wool and then experiment with some types of paints he had never used before.

He’ll also work on etchings, as he usually does come winter, a seasonal pursuit and an artistic medium that gives him as much pleasure now as it always has, warming his studio with the heating table he uses to make his inks more viscous.

Comments

His artwork is amazing!

Thanks for this inspiring profile

great article! thanks for the introduction to such an interesting artist…

I enjoyed reading this. Thanks!

I was a student of R.A. Parker back in 1959/61. He was an illustration instructor at The School of Visual Arts in NYC.

I have never forgotten him. A great influence for me and so many other students. A great article, I am so glad he is still painting.

This was an amazing read and it was so enjoyable seeing his art and creations. Will spend more time in the future on this site and the Visual Arts Project information.

Thank you for the experience.

Leave a Comment