In Memoriam

October 18, 2015

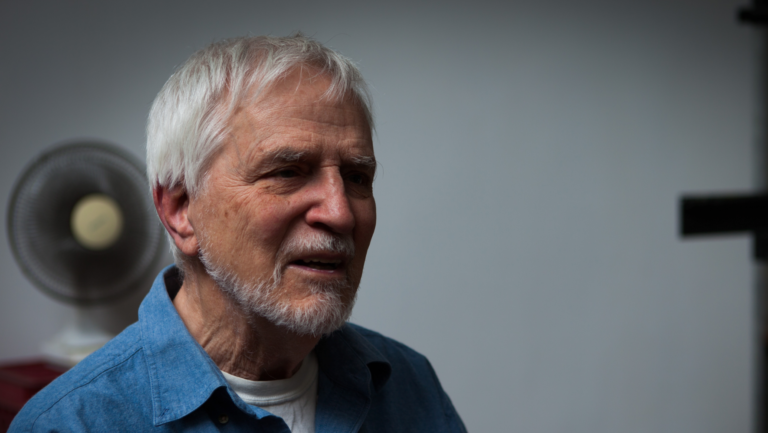

Remembering Lennart Anderson.

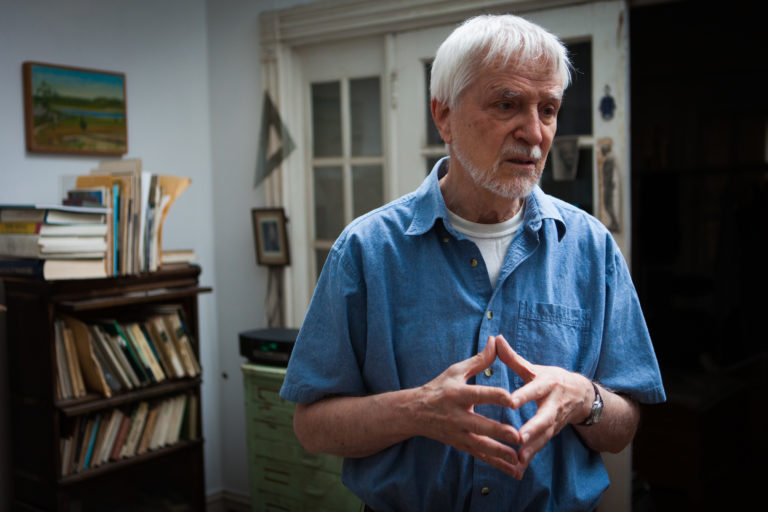

We are deeply saddened by the loss of Lennart Anderson, a perceptual painter, a painter of the figure, a painter of still life and of landscape in the spirit of Edgar Degas and Edwin Dickinson and others that he admired, a painter whose manner and style of painting did not preclude the desire to invent, imagine, and draw forth from an inner vision.

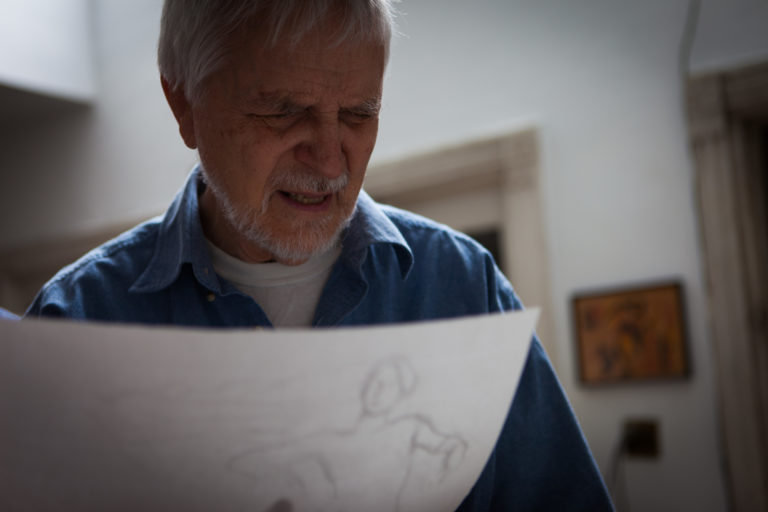

Throughout his life he worked and reworked his paintings, ever searching and revising, shaping and reshaping his distinctly rich palimpsest of marks and textures. The patience this open-ended working process required suited him well, increasingly as his vision began to fail due to macular degeneration a little over 10 years ago. Unable to imagine a life without painting, he adapted his working methods and continued to produce inspired paintings until the end.

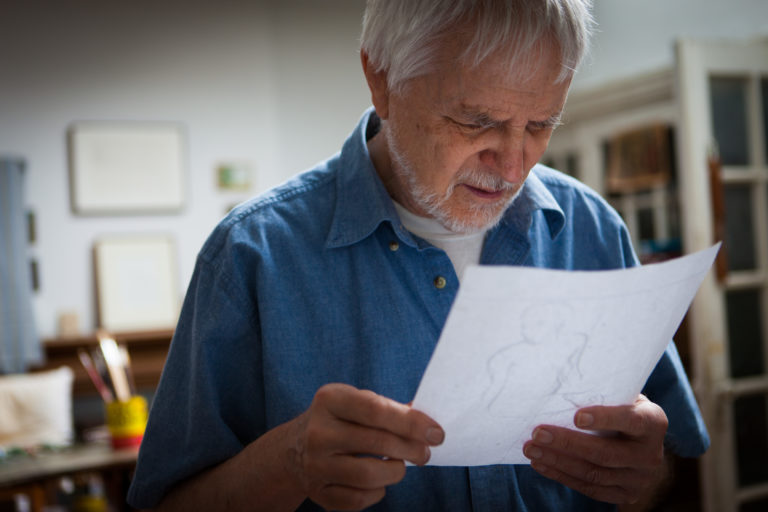

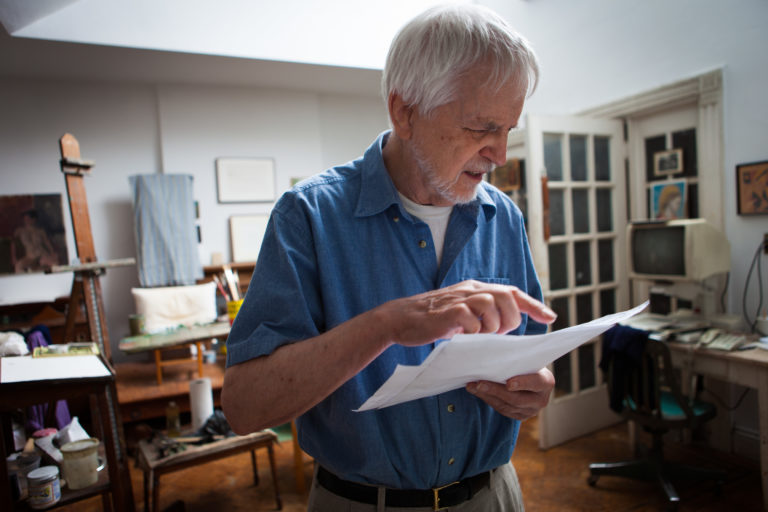

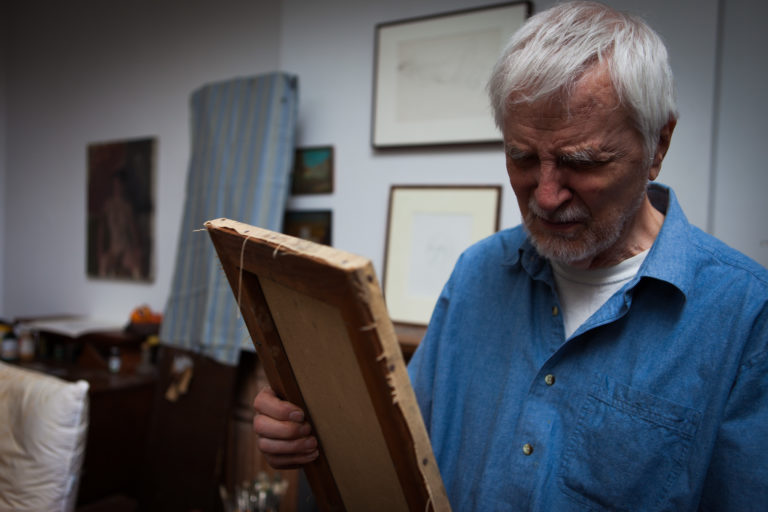

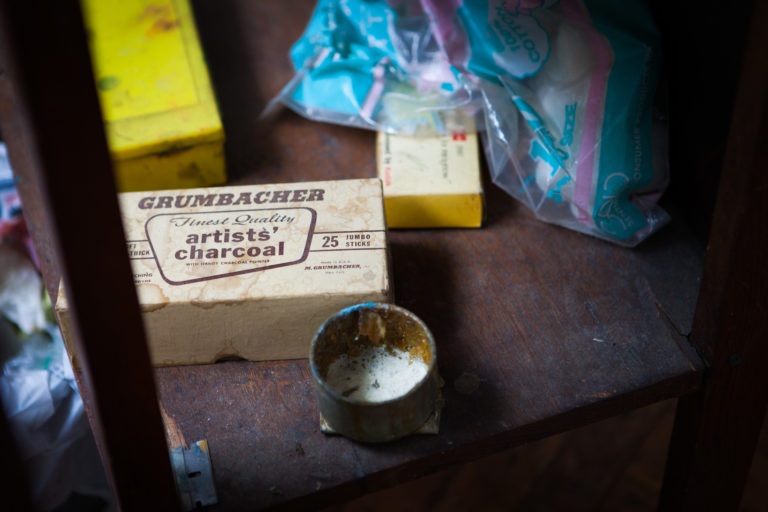

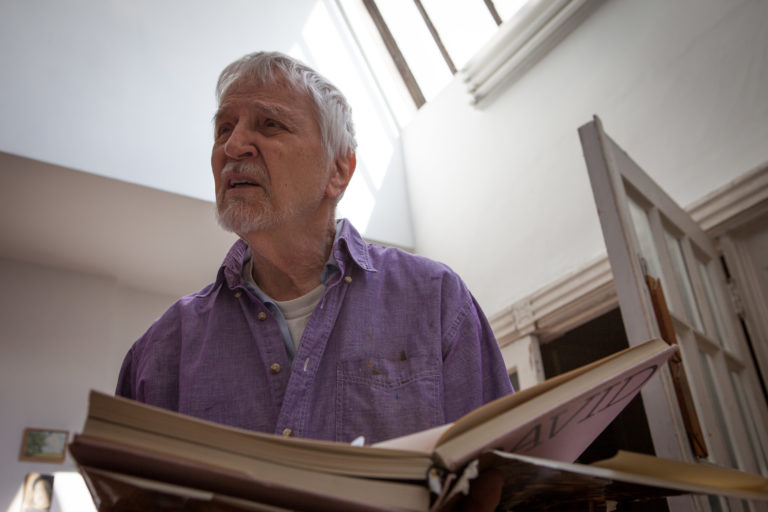

Though as practicing artists ourselves we had admired Anderson’s work from the time we were painting students in the mid-1990s, our friendship with Lennart began when he invited us to his studio in January of 2012 for an interview. We had begun a project for the American Macular Degeneration Foundation (AMDF) profiling artists with macular degeneration, and Lennart was the first contemporary master we had the privilege of working with. His studio was much as we expected it to be: a small skylit room on the top floor of his Brooklyn brownstone, arrayed and cluttered with stacks of heavily used art books, mismatched metal folding and wooden chairs of many sorts, easels, potted plants, coffee cans full of bristle brushes, the sounds of Bach in the air. A dozen or more small charcoal sketches were pinned haphazardly to the various open spaces of plastered wall that surrounded his central work space, and oil paintings hung in gilt frames, some of them his own work and some given to him by his many students, friends, and colleagues. The walls of this space were a neutral, off-white that together with the natural light from above was ideally suited to working from life.

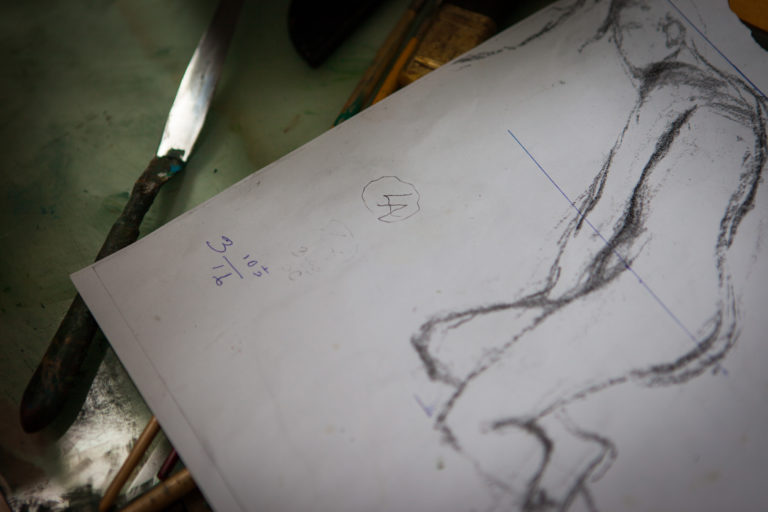

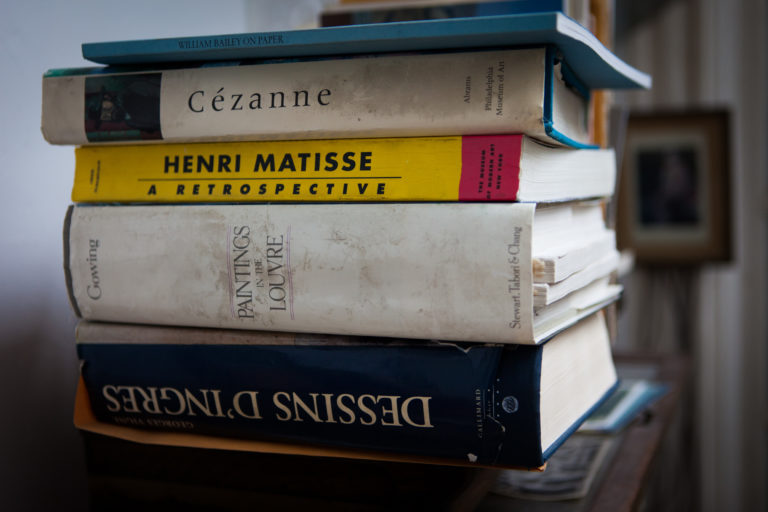

In the corner of his studio, one piece of furniture seemed especially emblematic of the artist: an old and well-used armchair. It was set within reach of an assembly of old stereo components, a stack of dusty, cracked CD and tape cases, adjacent to a fireplace trimmed in hardwood oak moldings. The armchair’s striped red and gold silk upholstery was threadbare, the springs flattened, and the seat cushion turned over to provide second life to that which had been worn beyond use. A heavy wooden elementary school chair next to the armchair served as coffee table, making ready a stack of art books several feet high. These books were stuffed with dozens or more paper scraps marking Lennart’s favorite images. Edges of the stacked books bore dark fingerprints, stains worn and polished from the painter thumbing through them over the course of decades of study and contemplation. A monograph of the works of Ingres lay on top of the pile, with Ingres’s painting of Princesse Albert de Brioglie in a blue satin dress on the dust jacket, on top of which Lennart had placed a magnifying glass.

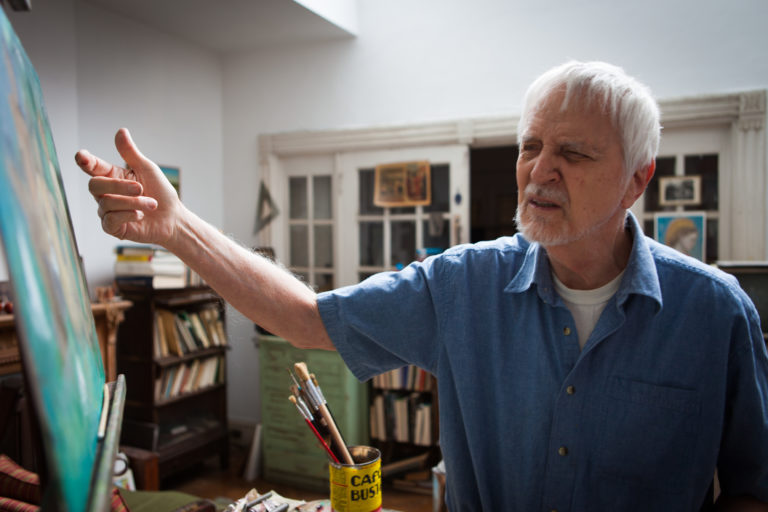

At the time of our first visit Lennart had recently abandoned a portrait he was painting from life and was putting the finishing touches to Idyll III, the Llast of a series of three multifigured bacchanals he had begun many decades earlier and had continued to work on for over 30 years. As we talked that afternoon, he often squinted and craned his neck, scratching with his fingernail at the surface of his painting. We asked how he was able to continue on as a painter now that he was legally blind. Beyond acknowledging in a rather matter-of-fact way that painting was more of a challenge than ever because he couldn’t see the colors on his palette, couldn’t ascertain his work in a single glance, couldn’t place his brush where he wanted, and was beset with declining confidence, he was not able to explain how he was able to continue his work on Idyll III. It was simply that the painting was not yet done, and he was determined to finish it, however that might be.

With his signature ability to speak honestly, even irascibly, yet with humor and warmth, he exclaimed, “You know the thing is…, people come and say, ‘you’re still working on that painting?’ They won’t say, ‘oh my God, what a wonderful painting now.’”

Like so many others before us, we felt immediate affection for Lennart, after only a few hours in his company.

Over the course of the next three years we spent many hours and days with him in different contexts—in his studio, over lunch at his favorite Chinese restaurant, at his summer home in Maine—talking with him about his life, his painting, and the world in which he lived.

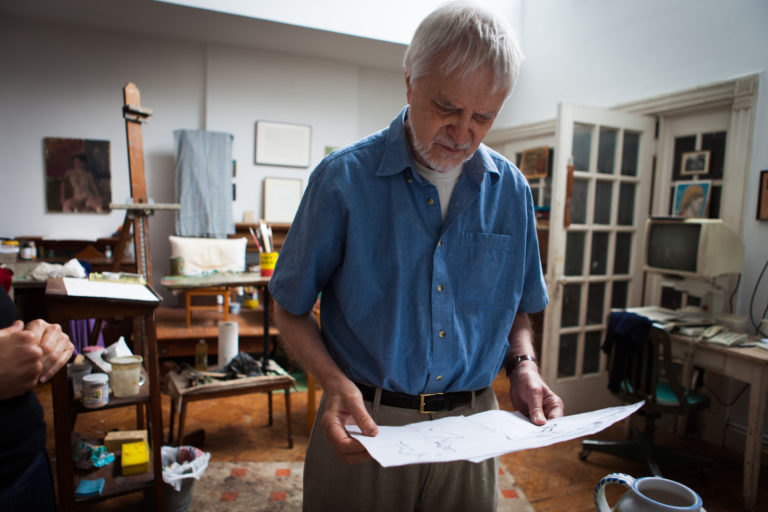

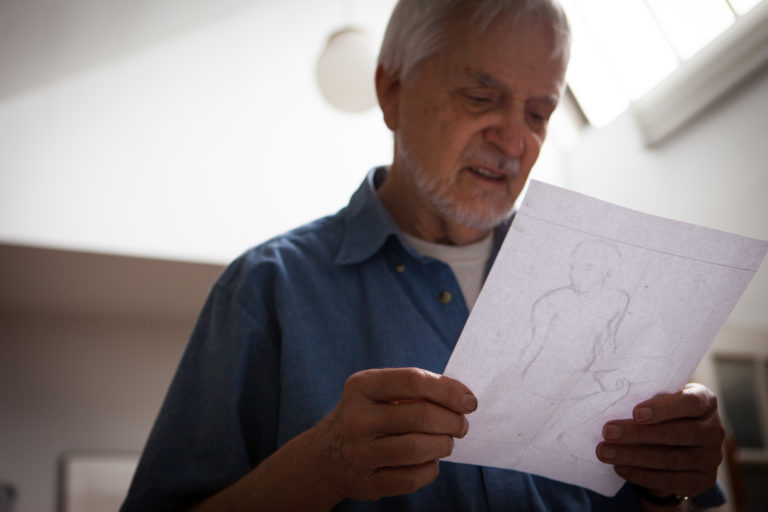

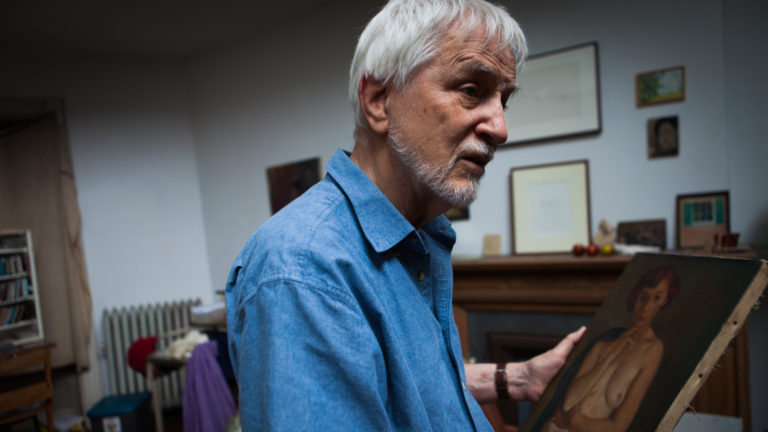

On one such occasion, in company with the photographer Jason Houston (whose photos accompany this article), we had arranged to try something unique to us as writers about artists: to have Brian paint a portrait, and to have Lennart (our real subject) stand by as instructor and critic to Brian’s work just as he might have done with the students he had taught over the years. Our hope was that an exercise of this nature might spur more spontaneous conversation and give us unique insight into not only his teaching style but also his philosophy of art-making, and the manner and nature by which he continued to navigate with what little remained of his vision.

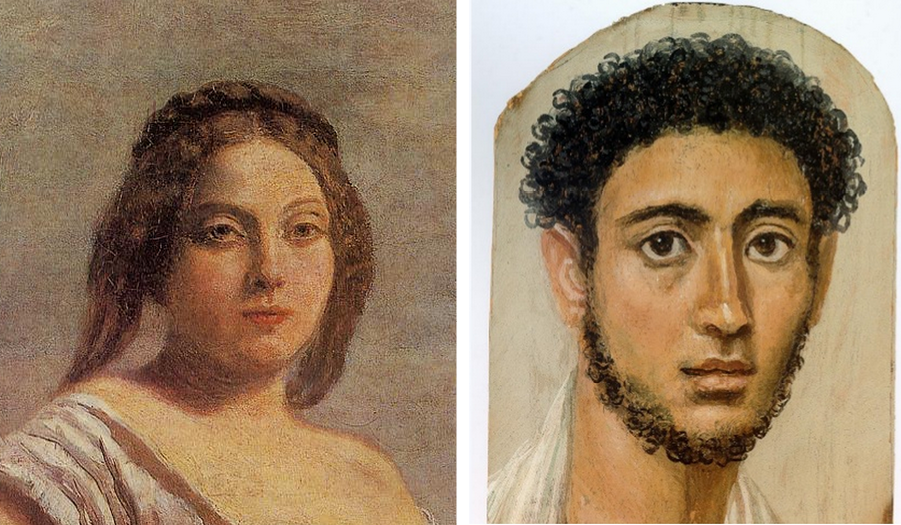

The summer afternoon in question, we showed up with a paintbox and brushes in hand. Lennart generously offered up a wide range of hand-gessoed panels to paint on. In preparation for the day’s painting, Lennart had also pre-selected two historically significant portraits for Brian to “consider” before he began to paint: a muted, simple Corot of a young girl and a Faiyum portrait of a young boy. As Brian considered these portraits and laid out paints on his palette, Lennart positioned me on a metal stool, turning my head to a slight three-quarter view overlooking my left shoulder. Lennart sat back in his armchair and watched Brian begin. Now and then, he spoke about a range of subjects—the three points that were crucial to him as a starting place for any work done from life, the way natural light falls delicately and predictably across a subject, the long, graceful gestures he would point out to students when he taught figure drawing at Brooklyn College, the importance of seeing broadly, of not getting caught up in meaningless detail.

At one point, Lennart grimaced and rose from his chair as Brian focused his brush on a detail around my eyes. He walked over to the easel and put an arm around Brian’s shoulder, reached over to the canvas with his other and dragged his thumb across the wet paint. What had been my eye and nose fused to become one unified gesture, deeply flawed in some ways but now both more alive and more closely resembling an actual likeness to me, the subject.

This event, as well as many other conversations we shared, helped us to understand that there is vision that reflects some measurable physical phenomena, or one’s sight; and there is vision that reflects some immeasurable quality of perception, or one’s aptitude for insight. Lennart remained at the crossroads between these two throughout his career. He had a staggering capacity to see and a staggering ability to transform or transmute what he saw in his mind’s eye, informed as it was by his deep humanity and the explicit dialogue he carried on with artists of the past. As his vision declined, he had to rely increasingly on the memory of his capacity for sight to inform work that increasingly revealed his insight.

At the end of a recent video profile about Lennart produced by AMDF in 2013, Lennart asks, “Why do I paint? Because I see beautifully. I hope you know what I mean by that. It’s beautiful out there. …”

Lennart was a man who lived bravely with what can be a disabling disease, an artist who in his twilight years was still painting with the same sensitivities and convictions as he had 50 or 60 years earlier—articulate, inspired and original—rising to face his canvas every morning with only shards and fragments of sight remaining to guide the course of his work. He was also a devoted father, a loyal friend, and a luminous human being who continually reminded us of our shared humanity, perhaps the most important legacy of his artistic vision.

Although we knew he was struggling with prostate cancer, the news that he had passed away came with no less of a sense of loss, and with that the awareness that the conversation we had with him during the past summer in Maine—in which, among other things, he talked about how meaningful the words faith and acceptance had come to seem to him—would be our last.

Lennart had a way of making you believe that there was always something more to say, something more to appreciate and to perceive, to enjoy, to learn, to pay homage to with paint and canvas. In the face of this loss we are more grateful than ever to have shared in his light, and grateful, too, that through his paintings, we can continue to consider the world through his eyes.

Further Reading

Lennart Anderson

“Seeing with Light:” A Film Profile of Lennart Anderson

In this short video profile, Lennart Anderson talks about his life. He also works on a portrait of fellow artist Kyle Staver.

Read More

Comments

Thank you for your sensitive comments about a dear friend and great painter. It was a great privilege to have known this extraordinary man.

A wonderful tribute. I wish I’d had known him.

Thank you for this writing and for all of these pictures most especially. Thank you, thank you.

I had the privilege of spending Saturday’s with Lennart for two years atBrooklyn College. He was a wonderful Professor and said he hated it when students cried. After my dad died I had a crit and cried when he told me I could paint as well as anyone but would have to work harder and paint more than

once a week. He was such a kind man that when I cried he apologized and was so uncomfortable I told him it was because my dad had recently died. Thank you for your writing he was one of a kind.

Beautiful. Thanks for sharing.

This is a wonderful piece of writing…thank you so much for sharing this beautiful tribute to Lennart Anderson. You managed to glean some essential things that we all can remember and hold on to in our own efforts…he can teach us still.

So very wonderful. Thank you.

Leave a Comment