Art Inhabits the Terrain of the Paradoxical

June 12, 2017

The Bogotá-based artist Doris Salcedo, who has macular degeneration, has been making astounding sculptures and public installations in response to political violence since the early 1990s. On the occasion of her recent exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums, we had a chance to interview her about vision and art.

Until recently, Salcedo’s work primarily concerned the more than 90,000 Colombians who have disappeared in the past fifty years, 70,000 of them without a trace. Her mission is to materialize absence, to evoke the memories and images that are still present in the seemingly empty spaces where the living were murdered, or from which they vanished. She believes violence will really end only if, “many more people decide to remember.” Toward that end, her works of art are offered as “acts of mourning.” Her poetics of mourning is rooted in her belief that, “art cannot explain things, but at least it can expose them.” Embodied within her work is a wide range of apparent binaries—presence and absence, hope and despair, remembering and moving on, individual lives and collective experience.

Her memorials are built out of once living objects that impart a visceral sense of pain and injury. They offer, as through a veil, an elusive glimpse of meaning and loss. Cow bladders are fashioned into filmy windows. Through them, we see into cubicles containing the shoes of the murdered. She also uses the artifacts and furniture of daily life in her works: tables and chairs that, ruptured from their quotidian function, possess the ghostly presence of those who are no longer here to use them.

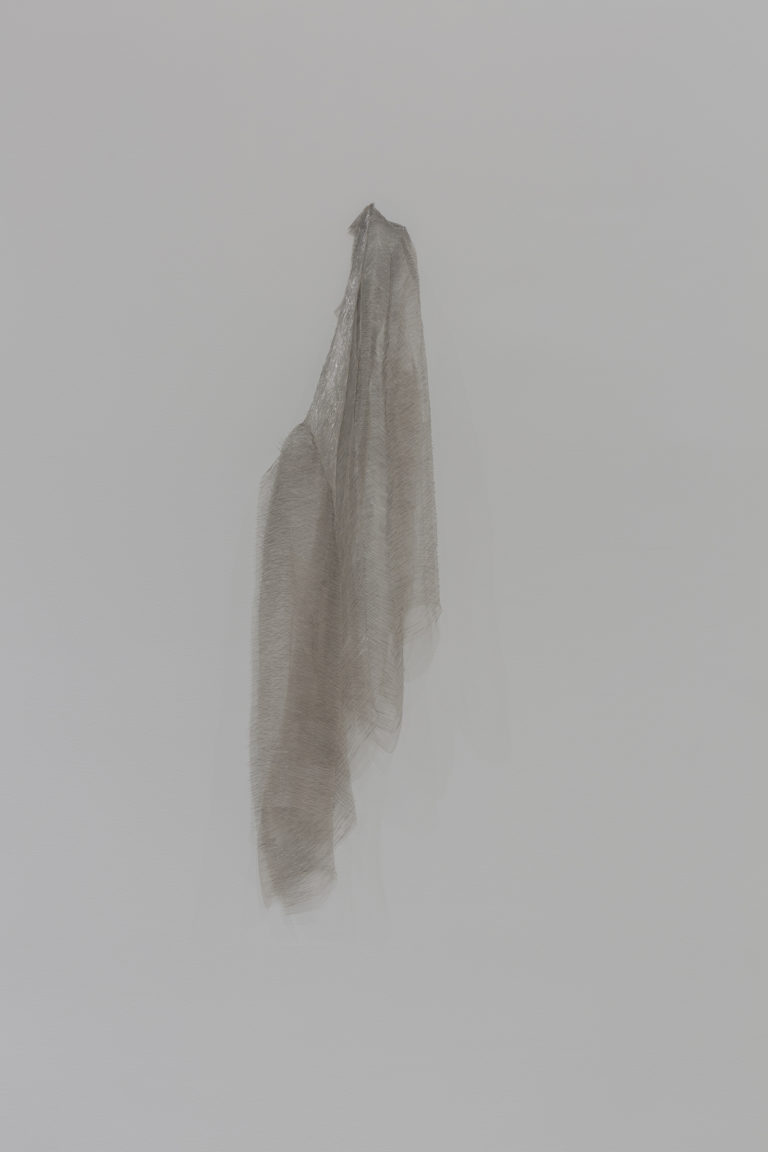

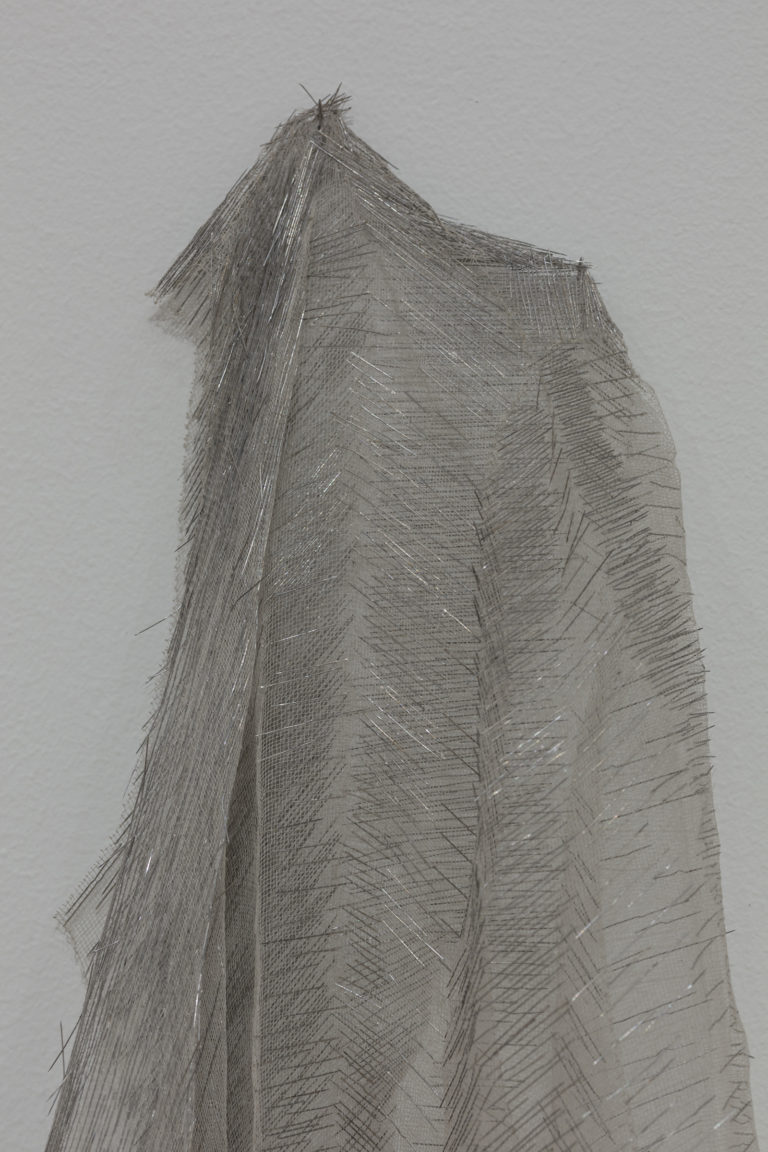

In recent years, some of her sculptures and installations have become more monumental in scale and included victims of violence beyond Colombia. At the Tate in 2007, for instance, Salcedo created Shibboleth, a jagged chasm stretching the length of the floor in Turbine Hall, meant to conjure the racist divisions underlying the modern world. Her 2014 Disremembered series, an assemblage of ethereal cloaks woven from silk thread and steel straight pins, memorializes the pain of African-American mothers who have lost their sons to gun violence in Chicago.

Salcedo’s exhibition at Harvard Art Museums, “The Materiality of Mourning,” (November 4, 2016-April 9, 2017)

Viewing this exhibition in person was an astonishing experience in physical and emotional terms. I was left feeling indelibly grateful for the poignant beauty of daily life—having a meal at a table, for instance. And indelibly shaken by the heartbreaking destruction of the spaces and rhythms of existence when violence intrudes upon them.

In two untitled works from 2008, wooden tables, armoires, concrete, and steel are fused together so as to make the individual items unusable. The careful attention to craft in the joinery recalls the human hand, human touch, human care, human tenderness. At the same time, the physical and spiritual presence of weight—and its inevitable evocation of a body immobilized by death—feels unbearably brutal.

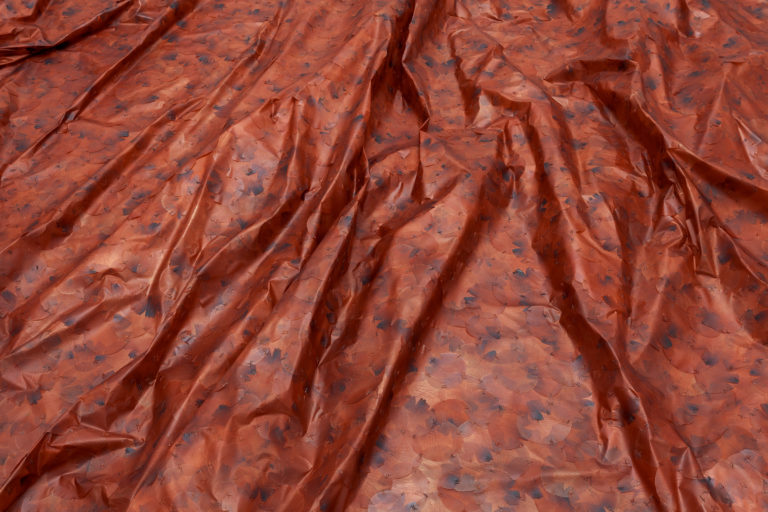

In other works, cast metal chairs have been beaten, ripped apart, and upended—bearing, as a body does, terrible marks of abuse. A Flor de Piel, which memorializes a nurse who was kidnapped and tortured, is constructed out of rose petals sutured together with thread. With a faint smell of flowers and wax, reminiscent of religion, it cascades over the floor like an animal skin, or a wide pool of darkened blood.

Interview: Doris Salcedo

In the following interview, Salcedo, who has macular degeneration, discusses her insights into vision and art, from the perspective of someone who adamantly believes that “[A]rt is a way of thinking, and in order to think you do not have to have perfect vision.” Her vision loss, she feels, while never defining her art or her life, has imparted empathy and a communal sense in her works.

A’Dora Phillips: When and why did you decide to become a sculptor?

Doris Salcedo: It was not a conscious decision, drawing and playing with materials was part of my life from a very early age. Fortunately, I had a very supportive mother—she sent me to drawing and other related art lessons as a child. Art was always part of my life.

Phillips: You were very young when diagnosed with macular degeneration. In some ways, your career as an artist was just starting. Did you ever worry about what your diagnosis might mean for you as an artist?

Salcedo: I understood my sickness as an element that was inherent to myself, like the color of my skin or my height, but it is important to state that having low vision has never been the center of my life. It has neither defined my life nor my work.

My work is based on the extreme experiences of victims and survivors of violence. This implies that I am not focused on what is happening in my life or my body. Observing carefully the experience of fellow human beings relativizes what is happening to oneself.

Nevertheless, macular deterioration has had a big impact in my life. As time goes by and my vision deteriorates, I have learned to deduce that which I can no longer see. I am constantly searching for new visual aids that can facilitate my everyday life and my work as an artist. I think it is important to say that for me art is a way of thinking, and in order to think you do not have to have perfect vision. For me art is an attempt to comprehend reality. Art is a way to expand the narrow definitions we have of what it means to be human.

I think it is important to say that for me art is a way of thinking, and in order to think you do not have to have perfect vision. For me art is an attempt to comprehend reality. Art is a way to expand the narrow definitions we have of what it means to be human.

Doris Salcedo

Art goes beyond my visual impairment—it is about empathy, and it is about a political and an artistic commitment.

Phillips: What kinds of adaptations have you had to make as an artist as a result of your vision?

Salcedo: At the beginning of my career I used to do everything by myself, with great detail and careful craftsmanship. Nowadays, in a way I do a similar kind of work but with the help of generous, intelligent studio collaborators.

I am not sure this change came about only because of my eyes. My work has acquired a monumental scale and also for this reason I need more help in the production of complex, labor-intensive and large-scale pieces.

It has always been important for me to produce pieces that could not possibly have been made by a single person.

Art inhabits the terrain of the paradoxical. For this reason, the pieces that I think [about] in the solitude of my daily drawing, can also be a collective articulation destined for the political arena that we all inhabit.

Phillips: Has your vision opened up alternative ways of seeing and experiencing the world that find their way into your work? Has it led to insights and opportunities?

Salcedo: My vision problems made me understand that I am fragile, vulnerable, and at times powerless. And this has enriched my capacity to feel empathy towards those who are in similar circumstances because of war, poverty, and violence.

Phillips: Along with the materiality of your work, language seems crucial to it—from the interviews you do with survivors, to the often untranslatable titles. What do you see as the role of language in your work? I have a powerful sense that the words of the survivors are embedded in the materiality of the final pieces—and that there is an aural quality to the silence—but can’t identify where and how.

Salcedo: Your question is quite precise; it addresses both language and the silence present in my work.

Every one of my pieces is based on the testimony of a survivor of violence or the experience of a victim narrated by a mourner. Words spoken during those interviews tend to define the limits to which I restrict myself during the process of making a specific piece.

Pain resists language; for this reason I try to address in my work those aspects of the violent experience that cannot be uttered or articulated in language. For me, materials and the ways in which they are transformed into an image, are the vectors that can bring to us the complete meaning of a human experience.

Leave a Comment