Dahlov Ipcar’s Enchanted World

February 21, 2018

We look back at the artist’s singular life and work on the first anniversary of her passing.

Dahlov Ipcar passed away last February at the age of 99. For eight decades, she lived at the end of a dirt road in the town of Robinhood on Maine’s Georgetown Peninsula. When, in 2015, I arrived to interview her in her neatly kept white farmhouse, it was as if Maine gave way to a sort of enchanted world: a low-ceilinged house with sloping floors and the colors and textures of patterned textiles and wallpaper, paintings, marionettes, sculptures, cloth figurines.

Using a walker, she led me to the studio she and her late husband had added to the house in the 1960s, seated herself in front of a shelf of her father’s sculptures (many of which depict her as a young girl), and waited for me to take out my interview questions and check my recorder. She didn’t ask about my drive or comment on the pouring rain, which drummed on the roof. She was not unfriendly. It was just that we had work to do, and she clearly believed in getting down to business.

From Beginning to End, a Life Steeped in Art

Ipcar was 97 at the time, and we talked about how deeply infused her life had been from the beginning with art and the making of things. Born in Windsor, Vermont, the daughter of artists William and Marguerite Zorach, she wasn’t formally trained in art, but her parents encouraged her to paint from an early age and served as her mentors. She was raised in Greenwich Village and attended City and Country School, a famous progressive school run by Caroline Pratt. From our interview:

I went to one of the very first progressive schools in the country. It was a marvelous school. I still remember the Egyptian plays and the medieval plays. Each year you’d put on a play in your class, and make the costumes and make the scenery and write the play. That was one of the things we did. I think it was important.

She got a full scholarship to Oberlin College and attended for one year, before dropping out because she found the teaching “dull,” focused as it was on memorizing, learning by rote, test taking. In 1936, at the age of 19, she married Adolph Ipcar, a young man who had been hired to tutor her in math. Within a year, they moved to her parent’s property in Georgetown, Maine. They sustained themselves as subsistence farmers and raised two sons in a milieu that was closer to the nineteenth century than the twentieth (no central heat, no refrigerator) while Ipcar also made art:

When I married, we stayed the first winter in New York in 1936, and we came here in 1937, the summer of 1937. We were going to just see what it was like for one winter, and we never went back. Everything was very primitive. There was no running water, no electricity, no bathrooms. You had privies.

A Solo Exhibition in 1939 at MoMA

Nevertheless, just a few years later in 1939 she was the first woman ever to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition, called Creative Growth: Childhood to Maturity, featured work done by Ipcar between the ages of three and 22. It was the inaugural exhibition in a special space at MoMA called the Young People’s Gallery, which was designed to serve the needs of art students. Ipcar was featured because she exemplified how a child, when properly nourished in her creative efforts, could grow into a full-fledged artist. Her father was deeply involved in the show’s organization.

Throughout the 1940s, she continued to show her work in New York. Her 1943 exhibition at Georgette Passedoit’s Gallery attracted notice from the New York Times: “Dahlov Ipcar… is no longer in danger of being known only as Bill Zorach’s daughter and a successful farmer. Early promise is being fulfilled and much has been accomplished since her work was used as the chronicle of a child’s progress at the Museum of Modern Art some years ago.”

Ipcar also completed several murals in the late 1930s and 1940s, for which she was paid between $600 and $700—enough for her family to live on for a year.

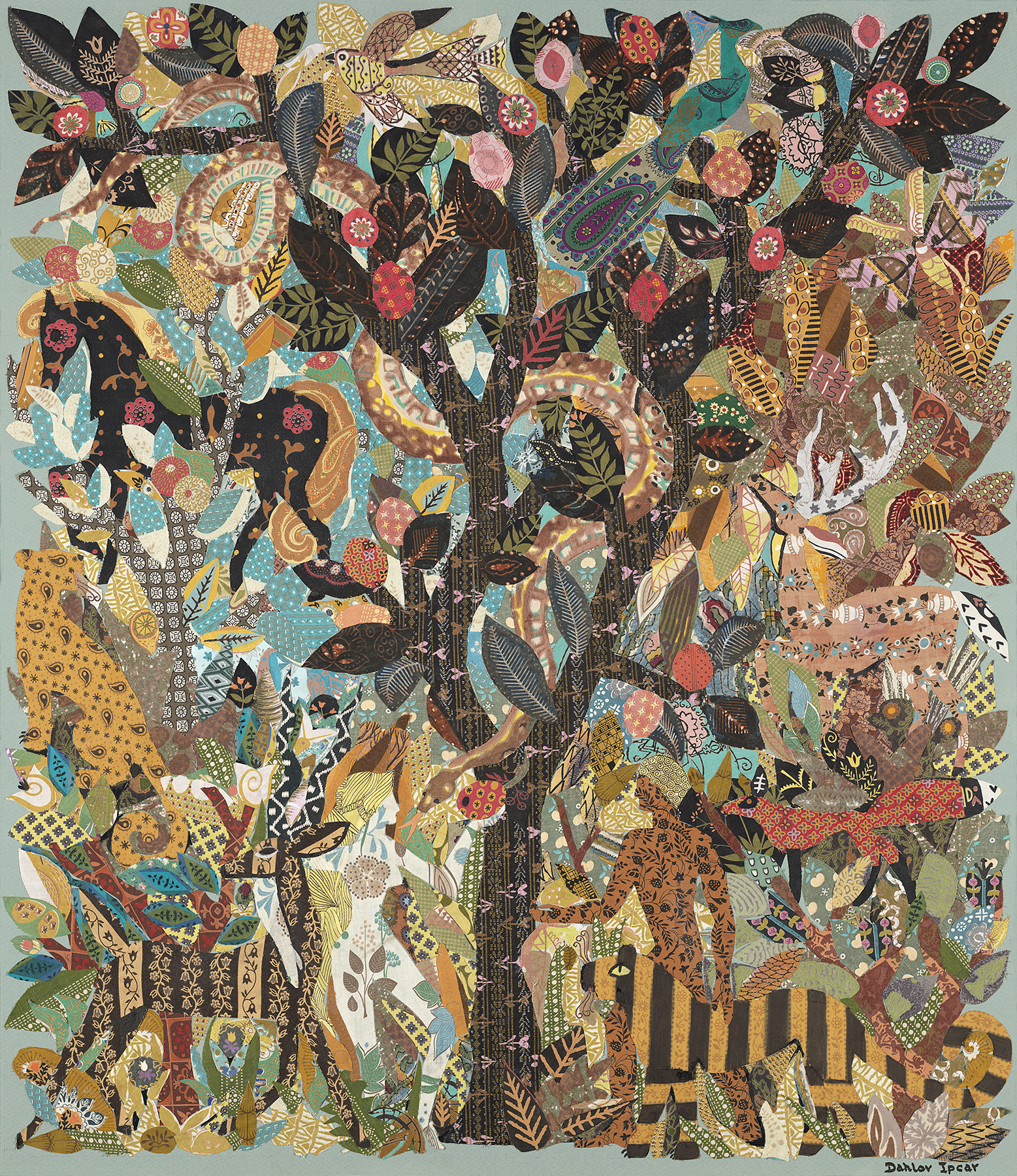

Non-Intellectual Cubism

Her work evolved from the social realist style she favored early in her career. On her own, she discovered an approach to painting that she termed “non-intellectual cubism,” which was to become her signature style. This involved a mannered approach to painting animals that emphasized design, set against backgrounds that had been broken into the prismatic shapes. Her approach was meant to depict “different areas of space and different parts of time in the same picture.” She felt this created an effect that was true to the real without being slavishly realistic. (Even by the age of 13, she had felt that it wasn’t realism, but “emotion and color” that constituted art.)

I found that I could put in a sort of cubist background. It wasn’t like a National Geographic panorama, which always seems so crowded with animals and things that it doesn’t seem natural. And while a cubism is not natural, it just seems right… when I see what artists consider reality is mostly, it’s a lot of drawing in it, and to me, it doesn’t look very real. And my animals are maybe stylized, but to me they have more life, and they’re more real, than most people’s, most artist’s.

Multifaceted, overflowing Creativity

In addition to painting, she worked in textiles, completing a series of cloth sculptures and a cloth collage called Garden of Eden, among other things. She also illustrated children’s books (most of which she wrote herself), getting her first big break in 1945, when she was chosen by Margaret Wise Brown to illustrate The Little Fisherman. She wrote several young adult novels that were, in her own estimation, surprisingly “macabre.”

I don’t know what drove me to write. It just happened. I know how the short stories happened, because I woke up one morning and remembered what had happened to me when I was five years old in Provincetown, and I said, “gee, that’s a story.” And I’ve written it all down, and it’s the first story in my book, The Nightmare and Her Foal. Everything in that story is accurate and true to life. Except I didn’t shoot anybody… To me, the writing was much more exciting than painting. I’d lie awake nights, you know, writing these stories, and thinking about them, and painting just sort of seemed natural.

Overcoming Late Life Vision Loss

Among the subjects we touched upon the day I visited her studio was that of her vision, an issue that clearly preoccupied her. She had warned me before I came that her vision had recently worsened and that she feared she had just painted her last work. It was of a panther and birds and, despite familiar subject matter, she was having trouble finishing it. In fact, in the time that had passed between my call and visit, she hadn’t painted at all and was clearly depressed about that. “I was always happy when I was painting,” she said, “and I miss it. It takes a big bite out of my life.”

This has been coming on a long time, and I sort of watched it develop. In the beginning, it was trouble with reading mostly. It didn’t seem to bother my art until just a year ago. I began to have difficulty with not being able to coordinate my hand and eye to get the details.

Now it’s like the fog has come in, and that makes it even harder. I mean, almost impossible. Things are in a deep fog now… You are wiped out. I can see your white shirt, and can see your arms and hands, and I can see your legs, but not much. I mean, I can just see they’re there. But your face and your head are gone. And anything on that side of the room is gone. That painting is gone. It’s just black over there, black fog. It’s not solid black, it’s just very dense, deep fogginess. And it gets into the middle of my vision when I try to paint something. My hand comes out and can’t see what to do. It’s impossible to do anything, because it’s just a blur.

Her most recent works were arranged on easels in front of us, including the painting of a panther she had mentioned over the phone. “I got this far, and stopped,” she said.

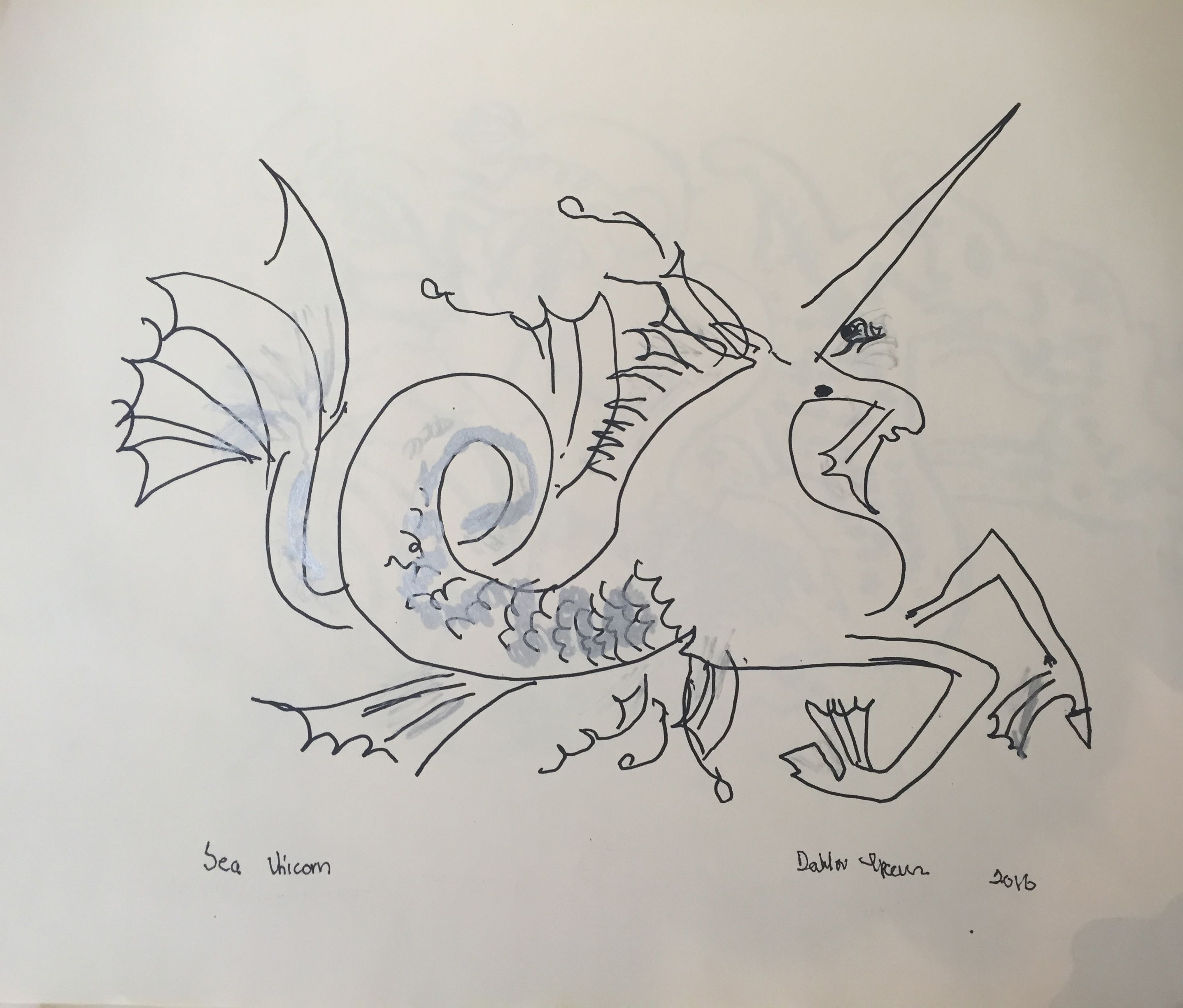

“The hand knows a lot, but it can’t see through the fog,” she said, explaining how she had articulated the panther’s form by tapping into the magnificent, fluid line that her hand remembered.

She asked if I knew of any artists who used assistants when their eyes became as severely impacted by macular degeneration as hers were. In the months that followed, she found that she retained an ability to create drawings of the animals that had long been a passionate subject for her and was able to paint with the help of an assistant. Her sons, who maintain a website devoted to her life and art, noted that on the day of her passing, February 10th, 2017, “She spent the morning at her easel… At age 99 she worked right up to the end, doing what she loved. We should all be so lucky… She left us a remarkable world to remember her by.”

Ipcar’s Legacy

In the year since Ipcar’s passing, a number of exhibitions have brought attention to this world of hers. The Ogunquit Museum of American Art remounted selections from her original 1939 MoMA show, which included some of her earliest works. (She dismissed this work as “childish” in a 1979 interview with Robert Brown for the Archives of American Art.)

Rachel Walls of Rachel Walls Fine Art (which represents Ipcar’s estate), mounted a comprehensive retrospective exhibit that included Ipcar’s last, assisted works. Walls also curated an exhibition focused on Ipcar’s children’s books for the Portland Public Library, and is working with Bates College on a major exhibition of Ipcar’s work this summer. Some of her children’s books have recently been reissued for a new generation of readers and have come to the attention of a wider reading public, but her painting is not well-known outside of Maine.

It would be a shame if Ipcar’s world and legacy were to remain largely limited to Maine, though Ipcar herself seemed to foresee (and accept) this possibility in 1979 as the price she might pay for living as she wished. As she told Robert Brown:

At one time I used to always sit here and think, maybe some great gallery is going to come after me and take me under their wings. But I don’t know if I really want it anymore because that’s a lot of pressure, too. And right now I’d really just rather stay here and do my own art. And if it gets forgotten in the future, that’s too bad, you know. …

One tends to be a little jealous of those artists who get great fame. But I don’t want what goes with great fame, you know, the celebrity and the—I mean, a guy like Wyeth is practically hounded to death. And even people, lesser people—I remember Blackie Langlais saying when he was in New York, he just—there was such pressure on to produce and produce and to socialize and so—you know, go to this—he hardly had time to do his work. And he got out of that. It was just too high-powered a scene. And I think I’m very much—the phrase now is “a very private person,” which I think stinks. But I’m a recluse or a hermit or something, or I’m just happy in my own little world which I create around me.

For more on Dahlov Ipcar, please check out The Vision & Art Project’s complete summer 2015 oral history with the artist.

Leave a Comment