Dispatches from the Pandemic: Art and Artists that Made 2020 Better

December 30, 2020

A remote conversation with the artist Virginia Knepper Doyle; an Oral History with Tim Prentice; learning about the under-known American artist Irving Guyer (1916–2012); and 2020 exhibitions of artists with macular degeneration that you can still see online.

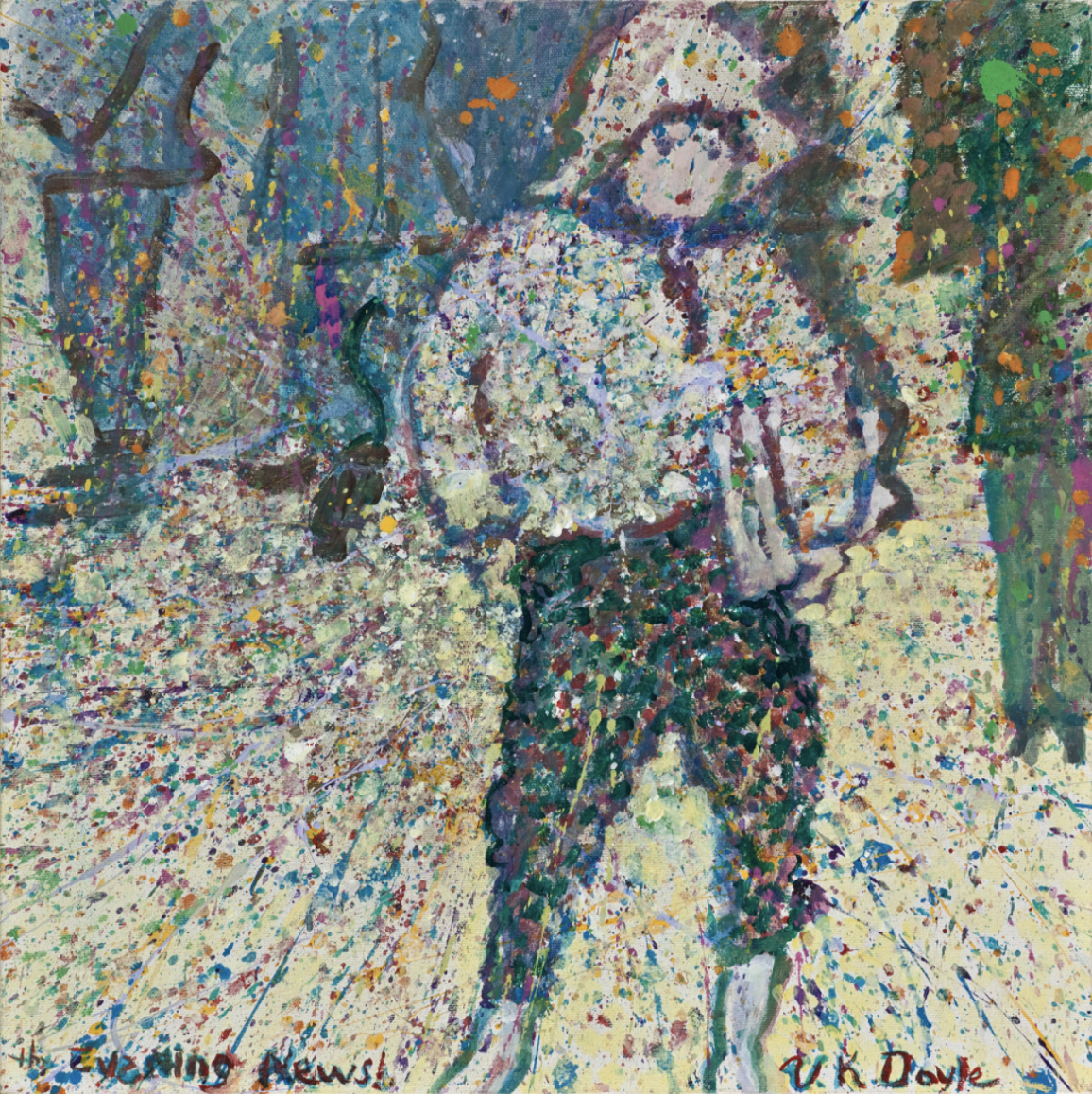

Virginia Knepper Doyle

Born in San Francisco in 1932, Virginia Knepper Doyle graduated from the University of California in Berkeley in 1955 with a BA in English and Psychology. She trained as an artist in studios in the United States and abroad while serving as a Foreign Service wife. She’s been showing her work since 1970 in exhibitions such as the World’s Woman Online Exhibit in Beijing, at Le Grand Palais in Paris, and in a Marin Art Guild exhibit juried by Kenneth Baker, The San Francisco Chronicle’s art critic.

Doyle lost most of her vision after a 2012 diagnosis of macular degeneration. We interviewed her via email about how making art has helped her deal with loss, including that of both her son and grandson this year. Our correspondence has been lightly edited for clarity.

Art involves feeling and seeing

“I mostly studied in the studios of well-known artists where I was living. I learned about etching in Geneva, Switzerland; oil painting in Monterrey, Mexico; design and color in Montevideo, Uruguay; and collage in Bethesda, Maryland and Cambridge, Massachusetts. I was influenced by the leading artists of the cities I lived in. For this reason my work reflects many different styles. In all, my work usually tells a story about feelings and, of course, reflects my ability to see at the time.

“I began to lose my vision to macular degeneration around 2012, after I had had a successful cataract operation and had my vision restored to 20/20. At first, I began purchasing stronger and stronger glasses. Then, an early treatment for my diminishing vision involved a laser treatment on my right eye. After several treatments, I was left with a scar that did not permit vision through it. I was terrified that the same thing might affect my left eye. When I did get macular degeneration in my left eye, I lost the ability to drive and to paint as I had always painted. My piece called Balance was a reflection of my fear—a figure in a nest, metaphor for home, falling and trying to grip onto the nest. Although I am falling, I am also dancing, so there was hope.

“I also created When Life Hands You a Lemon at the same time. It’s based on a photograph my doctor took of my retina, which looks so much like a landscape.

“I am legally blind and can describe what I see in general terms. Details such as a person’s facial features, writing, or anything small are hard for me to see. It is as if I am looking through a densely foggy landscape.

“Since 2012, my work has become looser and freer. Before that date, I did many impressionist watercolors and oil pastels, breaking up spaces in a controlled manner. For a few years after 2012 I did splatter painting, with complete freedom from composition, and loved this feeling. Then, however, I gradually returned to more design and texture, and finally what I call, ‘altered photography.’ My earlier work was on paper, landscapes of the San Francisco Bay Area, mostly.

“These days, particularly this year of a pandemic, I look for images that inspire me. I have always tried to see both sides of an issue, the positive and the negative, especially when there is a negative side. For example, this year of the tragedies of COVID-19 plus personal family tragedies of my son (57) and my grandson (22) dying, I have painted Garden with Cottage and several other works in which I try to show that the beauty of nature, no matter how severe the tragedy, is still there to greet us every day.

“The profound thing I have learned since vision loss is that vision loss does not mean that I have to give up painting. In fact, in the past two years, I have received two third-place awards in two very competitive exhibits in Chicago and in Marin County, California. I am creating every day with all the at-home time I have during the coronavirus pandemic. I seem to have gone back to basics…family, friends, painting, gardening, eating, and sleeping… In other words, living as an artist, my first love.”

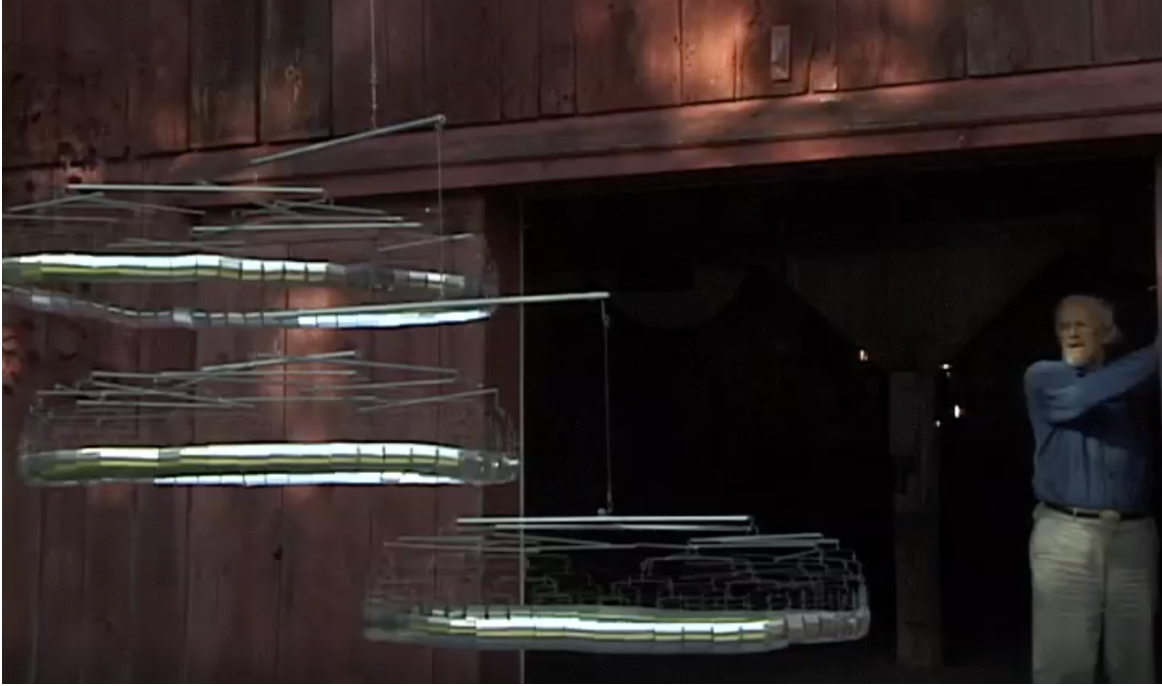

Kinetic Sculptor Tim Prentice

The one artist we were able to visit in person this year was Connecticut-based sculptor Tim Prentice, whose studio lends itself to social distancing.

While sitting in an outdoor shelter built on the footprint of an eighteenth-century barn, we talked to Prentice about his work in architecture before he became a sculptor and how architectural thinking infuses his artwork; some of the public art commissions he has taken on, such as the new Sandy Hook, CT, elementary school, Renzo Piano’s Aurora building in Sydney, Australia, and 11 Times Square in New York City; the four years he spent as a bombardier navigator during the Korean War and how it influenced him; his favorite tool, the spot welder; what it’s like to work with the wind, and Philip Guston’s idea that you can only truly get to work once everything that influences you—people, ideas, history, even your own self—has left the studio.

The entire interview is available with our other oral histories. Here are few excerpts:

On what Prentice thinks about when he works:

“The engineer in me wants to eliminate friction, to make the air visible, to make the air visible. The sailor in me wants to know the direction and strength of the wind. The artist wants to know the changing shape of the wind. Meanwhile, the child wants to play.”

On the art of getting things to move:

“Things can move without changing, and change without moving.”

On why it’s frustrating to be an artist:

“The hardest thing you can do, which I’ve almost never done, is to go in a shop and say, okay, today’s a vacation. I haven’t taken any national holidays in 16 years, or knocked off for Saturdays and Sundays. So today I’m going to go on vacation, and I’m going to go out of the shop and play. And that’s impossible.”

On his favorite art story:

“Philip Guston is my favorite art story… He suddenly left the city, and went up to Woodstock, and found a place in the country, and didn’t join the Woodstock society, as I’m told, but just worked on his stuff, and he remade himself from scratch, from the bottom up, became a different artist altogether. Didn’t go to his friends’ shows in New York, just stayed there and redid himself.

“What Guston had to say about this experience is that you go in the studio, and you’re following everybody you ever met. Your students, your family, your fellow artists, the critics, your neighbors, your parents. They’re in there with you, and you can’t move. And you have to be really, really, really patient and disciplined, and if you do that, if you are patient and disciplined, they start leaving one by one. And if you’re really lucky, finally you’re all by yourself. Then you’re not done yet. You have to be even more disciplined for yet more time. And if you’re really lucky, eventually, you yourself will leave. And then you can get to work.”

On partial sight loss:

“What surprised the dickens out of me is that I didn’t realize how much I could do with just feel. You can see with your fingers, in other words. I mean, for instance, people do their hair behind their head. They don’t have to see it. They don’t have to look at their shoe to tie it. We have all these things that we don’t realize, that our fingers know how to do.”

Note: We conducted our first interview with Prentice during the summer of 2019. It focused on his artistic influences and goes into greater detail about how he’s adapted to vision loss due to macular degeneration.

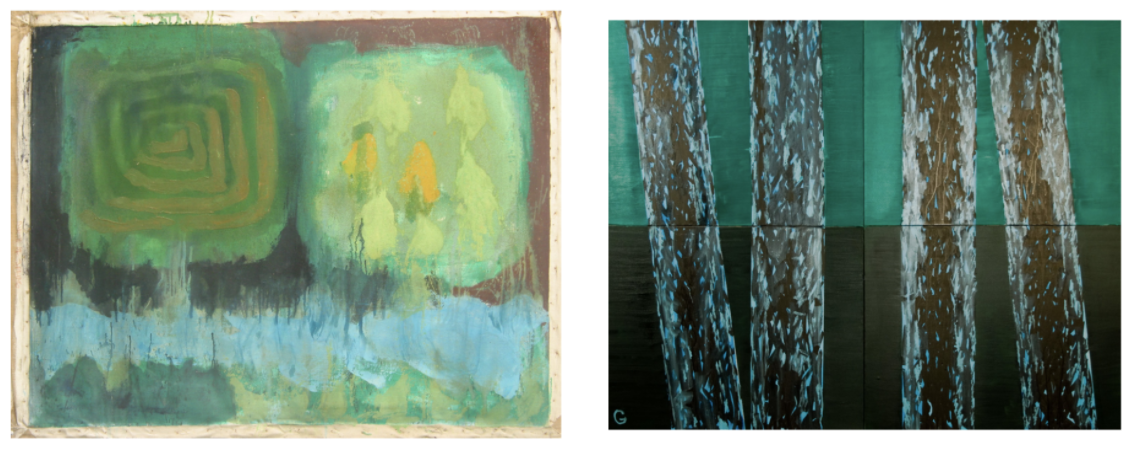

Irving Guyer

For varied reasons, outstanding artists sometimes end up being under-recognized. One such artist is Irving Guyer (1916–2012).

Guyer’s career began with the “improbable notion” he had from a young age of becoming an artist. Among his early successes, he won a first prize in painting at the 1939 World’s Fair. Many of his Depression-era works were acquired by important museums, such as the The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Brooklyn Museum of Art. He painted until just a few days before his death at 95, in 2012. At that point, he’d been suffering vision loss for several years.

His work and life—which we’ve learned about through his daughter, artist Léonie Guyer—felt particularly resonant to us this year. Like most of us since the pandemic began, Guyer spent much of his life working in relative solitude. After three successful shows in the 1960s at the Galerie Paula Insel in New York, Guyer chose to stop exhibiting his work, though he continued to draw and paint intensely and seriously. Not until 1981 did he exhibit his work again. By then, he and his wife had relocated from New York to San Francisco. Deeply moved by the Pacific Coast landscape and profoundly influenced by Henri Matisse’s cutouts at the National Gallery of Art in 1977, Guyer was “shaken up” and began to experiment with a new, simplified artistic vocabulary, one that carried him through the final decades of his career.

For more details about Guyer’s work and life, see our biography of him or visit his website.

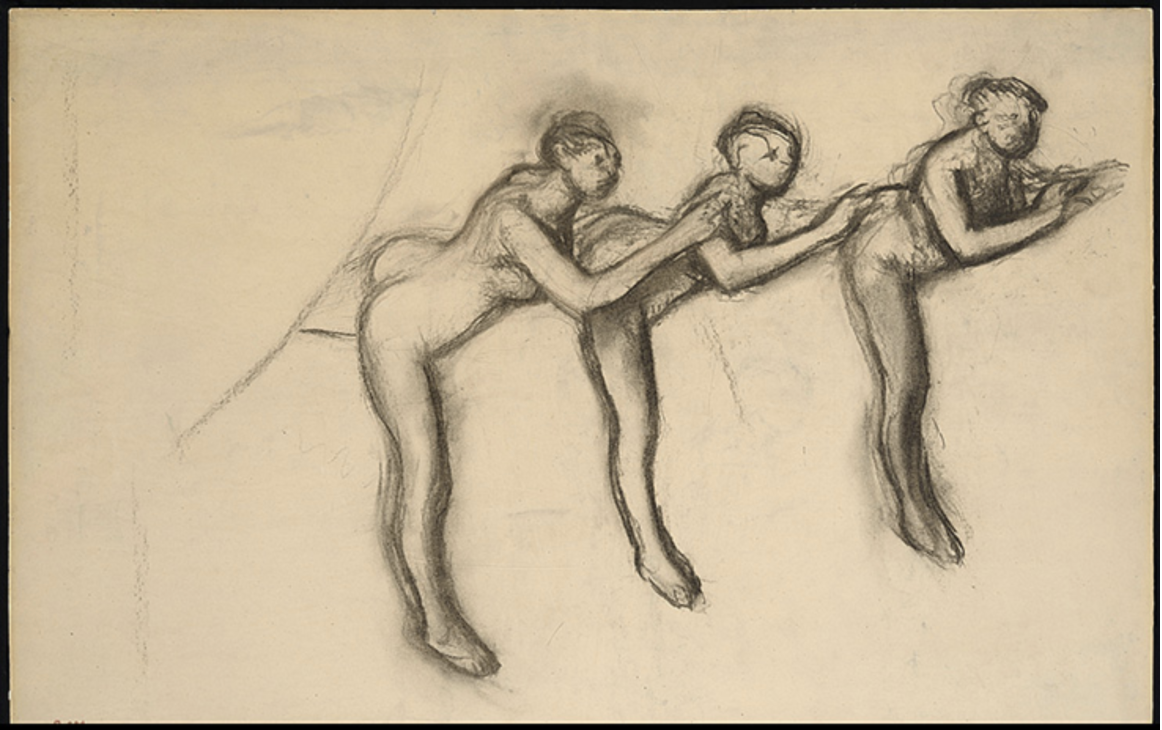

Degas at the Opera—The National Gallery

This spring, The National Gallery of Art hosted one of the best exhibits of 2020, a sublime collection of Degas’s work entitled Degas at the Opera. It was open for only two weeks in March before the gallery closed due to COVID-19. Hence, most of us had to view the exhibit via the virtual tour on the National Gallery’s website and related online audio and visual materials.

To complicate the notion of Degas the realist, the exhibit’s curators emphasized the role of fiction, fantasy, and feeling in Degas’s art. In the context of our work at The Vision and Art Project, this exhibition also provided an opportunity to circle back and reflect on the paradoxical interdependence of vision, vision loss, memory, and sight in his work.

Many of the great works in this exhibit date from the early 1880s and beyond, the period of time when Degas was in the early throes of managing his studio practice in the face of increasing vision loss. (Walter Sickert claimed that by 1883, Degas had difficulty seeing beyond his blind spot, one of the characteristic symptoms of macular degeneration.)

In Three Nude Dancers Executing Arabesques, (1892–1895), for example, we see the beginnings of the simplified forms so characteristic of Degas’s late life monoprints and pastels. By understanding the presence of his failing vision when this work was created, and by extension his hampered ability to work from direct observation, his increased reliance on memory becomes clear. It was a faculty that Degas praised highly in the making of art. He said that, while it might be “very good to copy what one sees, it is much better to draw what you can’t see any more but is in your memory. It is a transformation in which imagination and memory work together. You only reproduce what struck you, that is to say the necessary.”

Hedda Sterne at Victoria Miro and Van Doren Waxter

In 1993, living in a brownstone on East 71st Street in Manhattan, the 83-year-old artist Hedda Sterne’s vision began to falter. In spite of this, she continued to work as obsessively as ever. Still, for an artist who had been remarkably successful—she had exhibited in dozens of solo and important group exhibitions since 1941; seen her work acquired by major museums; and was the sole woman in the famous 1951 Life Magazine photo, “The Irascibles”—she had become strangely under-known and under-appreciated. When she was interviewed by Bomb in 1992, for example, Anney Bonney introduced her as one of the “best kept secrets in the art world.”

Almost fifteen years later, Josef Helfenstein wrote about Sterne on the occasion of a retrospective exhibit at the University of Illinois’s Krannert Art Museum in 2006. Like Bonney, he noted that art history from the post-war American scene rarely included her work. Many curators of modern and contemporary art, he wrote, didn’t know her name, much less her work or if she was still alive.

In the years since Hedda Sterne’s death in 2011, she’s gradually been restored to her rightful place as an important artist. She’d had two notable exhibitions this year alone. The first, Hedda Sterne, which opened January 29, 2020 at Victoria Miro in London, brings attention to a series of vertical horizontal paintings Sterne did in the 1960s. The second, Patterns of Thought, which opened on October 7 at Van Doren Waxter in New York, showcases a series of prismatic abstractions from the 1980s. They were among the last works Sterne completed before beginning to experience vision problems.

Both exhibits demonstrate Sterne’s focus on light. When considered as a continuum, balance, structure, and symmetry seemed to have emerged in the 1980s from the more inchoate light of the 1960s.

She’s an artist who expressed what perhaps many of us feel:

At all times I have been moved, to paraphrase Irish poet Seamus Heaney, by the music of the way things are… And through all this pervades my feeling that I am only one small speck (hardly an atom) in the uninterrupted flux of the world around me.

Leave a Comment