Drawing on the Air: The Kinetic Sculpture of Tim Prentice

Tim Prentice, Introductory Essay by Nicholas Fox Weber

Easton Studio Press, 2012

A review of Prentice’s 2012 amply-illustrated treatise on his work and of the 2021 publication, Tim Prentice: After the Mobile, a small catalog that accompanies his current show on view at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

Drawing on the Air

On a recent fall weekend, Tim Prentice, who we’ve interviewed at the Vision & Art Project, was one of the artists participating in the Cornwall, CT, Open Studios. When I stopped by to say hello, admiring visitors packed his studio and milled around outside, where he’s composed a collection of his kinetic sculptures, creating of his land a permanent sculpture garden.

Prentice had installed himself at the entrance of the barn that, among other things, serves as a showroom for his work. At 91, he is lanky and sociable. Along with selling his sculptures, he was happily selling signed copies of a 2012 book he produced about his work, Drawing on the Air. Though it’s been almost a decade since it was published, it remains a fascinating window into Prentice’s work specifically and kinetic sculpture more generally. Until recently, in fact, it was the only publication available about this significant but under-known American artist. Happily, it’s recently been joined by Tim Prentice: After the Mobile, a small catalog that accompanies his current show on view at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

“The air comes along and does the art.”

I mean this as no aspersion to say that Drawing on the Air is a coffee-table book—a book to be left out, picked up, browsed through. Part autobiography, part artist’s monograph, part technical treatise, it opens with an introductory essay by Nicholas Fox Weber, a writer and director of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, who paints a vivid picture of Prentice, his studio, and his materials. In doing so, he borrows liberally from conversations he’s had with Prentice, often weaving together his personal observations with things that the eminently quotable Prentice has said:

Tim Prentice’s way of communicating verbally is as unique as his work: the same mixture of playfulness and erudition. He uses his hands to guide a visitor through one of the shimmering, undulating constructions overhead and points out the fox trot relationship of its elements—the dance analogy is his—with the 2/4/8/16/32 progression that can be read into its forms. He amplifies: “What I think we’re doing makes sense when we find the patterns that evolve. We don’t set out to make them. We make the machine and keep our artistic instinct out of it and the air comes along and does the art.”

Transfixed

Aside from Weber’s introduction, Drawing on the Air is in Prentice’s own words. As befits a deeply visual person, he expresses himself briefly, succinctly, and often lyrically, otherwise allowing his artwork to speak for itself. His short chapter, “Early Signs,” strings together the flares that signaled from his childhood that he was destined to become an artist eventually, after a first career as an architect. Among what startled him into awareness: a favorite game that involved finding familiar objects that had been placed in unfamiliar places; watching through a window as his friend and his friend’s father played the violin together by candlelight; being held transfixed by a Calder sculpture during a field trip to the Addison Gallery in Andover, Massachusetts: “As I stared, I tried to visualize the artist’s hands bending the wire to find the balance.”

As part of his meditation on what moved him to become a kinetic sculptor, Prentice writes descriptions of movement and the wind that read like transcendentalist prose poems, delivering decades of experience and thought in a few short paragraphs: “The wind is moody, whimsical, and unpredictable. I thought that if I could capture these qualities the wind itself would be the work of art. I work for the wind. I like to imagine the air becoming visible.”

“I learned to connect a series of repetitive elements”

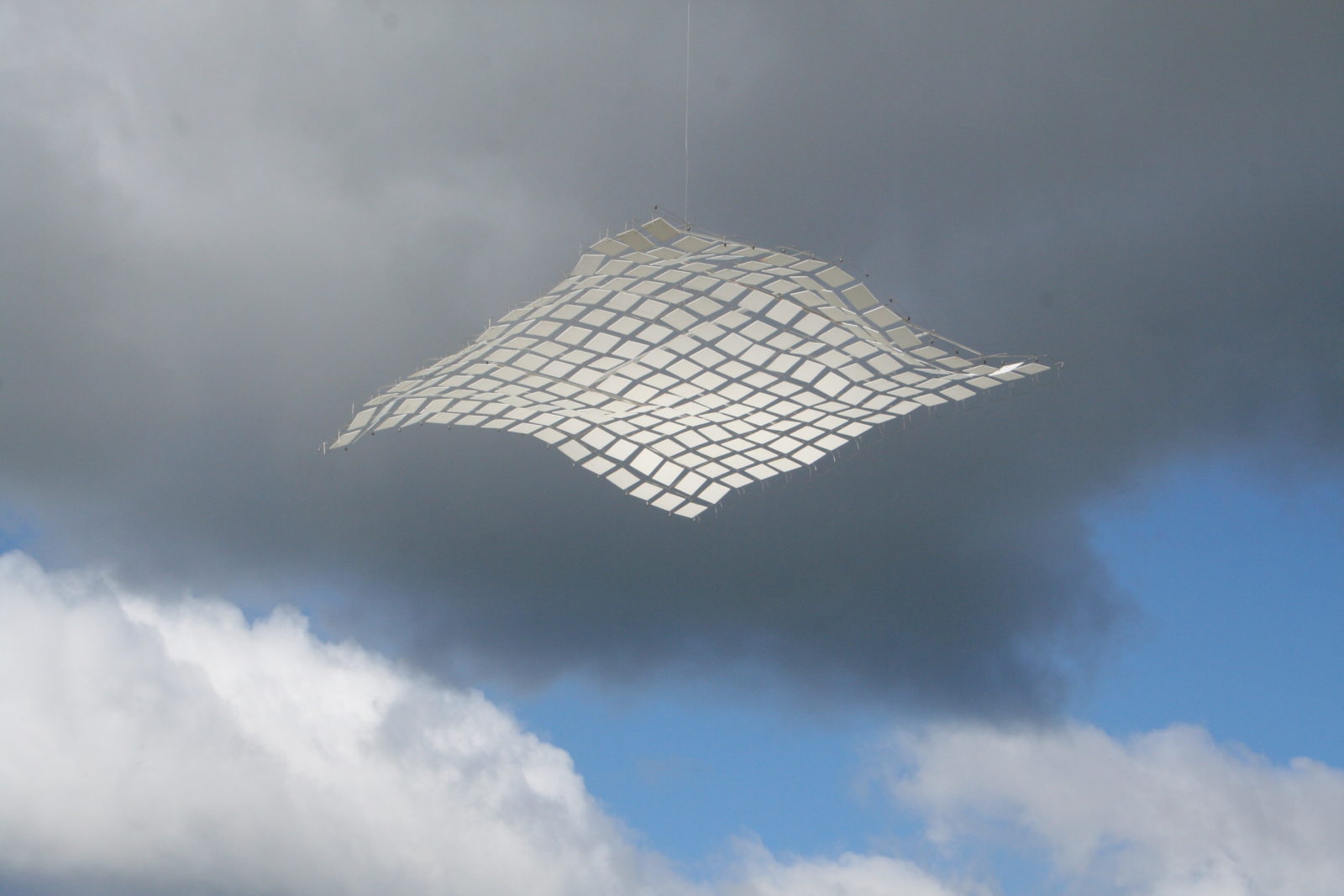

“Two giants” of kinetic sculpture, Alexander Calder and George Rickey, are among Prentice’s major influences, though as Prentice describes it, his work correlates perhaps most directly to that of Calder. Of Calder’s work, Prentice observes that his “carefully balanced forms are free to change their relationship in space.” When he faced the challenge of breaking away from Calder’s and Rickey’s influence, Prentice wondered if it would be possible to have not only the relationship between the forms change, but to also have the forms themselves change. In answer to this question, he’s spent decades exploring, experimenting, and inventing a unique typology of named forms such as “zinger,” “oculus”, “banner,” “curtain,” and “carpet,” each of which depends for its construction upon variants of repetitive bent wire linkages engineered, as Prentice describes, to “warp and bend according to the whim of the wind.”

While Prentice writes concisely about what he does and how he does it, Richard Klein, the exhibition director at the Aldrich Museum, elucidates in his essay in After the Mobile why what Prentice does is so exceptional. Prentice’s inventiveness, Klein suggests, allows him to reveal “more about the true nature of the wind” than either Calder or Rickey does. Because of how Prentice’s work is constructed, it ripples in the moving air and “changes its visual character in response to a breeze,” thus evoking the movement found “in leaves, tall grass, birds, clouds, or even wind-driven snow.”

After the Mobile

The small catalog in which Klein writes about Prentice accompanies the sculptor’s first solo museum show since 1999. The exhibition, which will run for over a year by the time it closes, is presented in two parts: inside the museum’s galleries (March 29–October 4, 2021) and outside in its sculpture garden (September 19, 2021–April 24, 2022). Its title refers back to Calder, whose playful mobiles Klein sees as coming out of the presiding ideas and values of his time, just as he sees Prentice’s art as emerging out of ours. Klein finds the rise in the past half-century of systems theory to be particularly relevant to Prentice’s work: “the insight that cohesive systems with interrelated and independent parts are resilient to external disruption, having the ability to move but always returning to their original form.”

In addition to Prentice, the exhibition acknowledges Prentice’s partner, David Colbert, who contributes a second short essay to the catalog in which he discusses how his work with Prentice developed and expanded over the years, starting in 1981 when Prentice hired him as an assistant.

Though Prentice’s commissioned works are in a number of important public and corporate collections, his contribution to art is not as well known outside of his local milieu as it ought to be. In Klein’s opinion, this is because, while Prentice’s work has been frequently commissioned, he hasn’t made gallery- and museum-oriented work, which has put him “somewhat beneath the art world’s radar.”

While photos of Prentice’s sculptures can’t convey the multisensory immersion of experiencing their motion in person, these two publications combine to help bring his richly deserving work to a wider audience. They also hint at what Prentice hopes to communicate through his sculptures: to “slow the viewer down for a minute, hold their attention, draw people out of their own concerns, get them to see something they hadn’t seen in an ordinary day.”