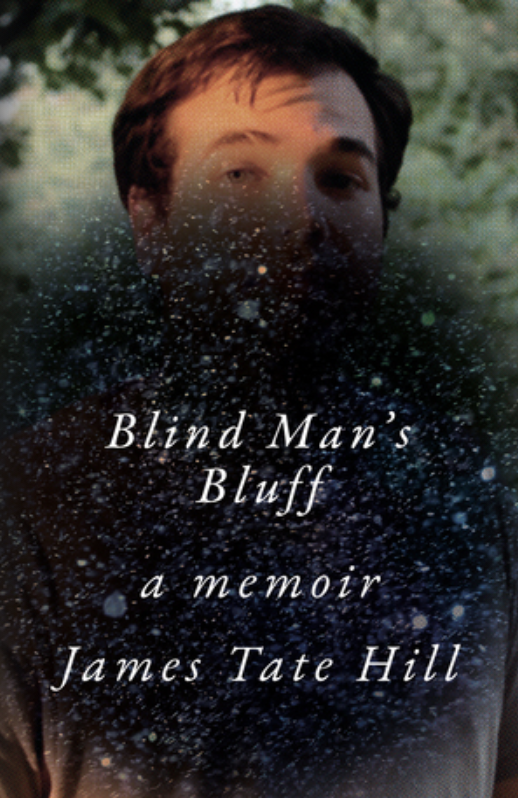

Blind Man’s Bluff: A poignant and humorous story of losing sight—and trying to hide it from the world.

James Tate Hill

W. W. Norton & Company, 2021

James Tate Hill’s “lie” that he can see

James Tate Hill was a comics-loving sixteen-year old from West Virginia when he was diagnosed with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, a condition that left him legally blind and is the subject of Blind Man’s Bluff.

Blind Man’s Bluff opens with a scene from much later in his life, when he has still yet to fully acknowledge (even to himself) his loss of sight. He has joined his first wife in Nashville, Tennessee, after living apart from her for a semester because they work in different cities. Their relationship is falling apart—from her perspective, because he wants her to be complicit in his “lie” that he can see. The tension is palpable as he unloads the car at his wife’s apartment, his mother (who had driven him from where he’d been living in North Carolina) still in attendance. His wife barely speaks to him. He retreats to the bathroom, buries his face in a bath towel, and begins to cry.

Looking into the bathroom mirror, he admits (to himself and the reader) that he can’t see his own face. We then leave this opening scene and head back to his junior year in high school year, when he starts to have trouble viewing the board. Even in these early stages of vision loss, his instinct is to hide what is happening. He goes to an optometrist, and, after being referred to various specialists, is diagnosed with a swollen optic nerve. He’s given steroids and expects to make a full recovery. Heartbreakingly, he keeps looking for signs that the vision in his left eye is returning. It’s not, even though at times he convinces himself it is. Instead, his right eye succumbs, as well, whereupon his condition is accurately diagnosed.

“Blind is a common synonym for ignorant”

From the beginning, vision loss is isolating, a condition made worse by Hill’s denial. After a stint in the hospital, he returns to high school two days before the start of summer vacation. Those among his teachers and fellow students who could start summer break early have gone, and he feels keenly the abandoned halls. At home that summer, unable to go out, he watches endless TV, which has become, as he says, “a radio.” He begins to memorize as much as he can—in some ways, a healthy adaptation, since he needs to know where such things are as the buttons on the microwave in order to retain a degree of self-sufficiency; in other ways, not, since he uses his memory to mask his blindness. He wants desperately to pass as sighted because, as he writes, “Blind is a common synonym for ignorant.” Throughout the rest of the memoir, he shows how, despite sensing that it makes his life more difficult, he persistently pretends that he can see.

In a pattern that repeats itself over and over again and that Hill dramatizes for us in his book, he makes a transition in his life (from high school to college, college to grad school, student to teacher), keeps the severity of his vision loss from his new associates, and lives an incredibly isolated existence until he’s able to integrate into a new community. You want to call out sympathetically to him over the pages: “Just tell your professors, girlfriends, colleagues, students, what’s going on!”

Typically, his (male) friends eventually discern the severity of his vision loss, and, tactfully, without his asking, help him with tasks like reading, shopping, and negotiating the walk from campus to town, thus also strengthening friendships. But his determination to hide his blindness wreaks havoc on his romantic relationships.

This begins with his first date as a legally blind sixteen-year-old with Maria, when he pretends to be able to read the menu at the restaurant they go to (the stress of not being able to read menus surfaces repeatedly in this memoir). His blindness also leads to misunderstandings, such as when he refuses to tell a professor why he’d not seen on the board that there’d been a classroom change for a course he was taking in graduate school. It leads to dangerous situations, such as when he tries to walk through busy traffic to the grocery store in order to convince his wife that he’s more physically self-sufficient than he in truth is.

A memoir about losing sight—and also about becoming a writer

Though this memoir’s main focus is Hill’s long process of accepting his blindness and finding love, it also tells the parallel story of his becoming a writer. Hill never says he wouldn’t have become a writer had he not gone blind, but he implies it. It was after he lost his vision, after all, that he was introduced to audiobooks through the Talking Books program and became a reader. (The memoir includes an interesting discussion of what it means to read, based on Hill’s experience with recorded books.) As for so many people, it was a short step from reading to writing. By his senior year in high school, he was secretly writing short stories and asking his English teacher to critique them. By his second year in college, he was taking undergrad writing workshops. He was eventually accepted into an MFA program and began the long process of building his career, racking up many requisite rejections along the way.

“Another shelf of memory claimed by everyday tasks”

Hill does a remarkable job with an economy of details conveying the terrifying disorientation of losing his vision:

“A custodian helps you open your locker, the combination too small for you to read. The clang of it closing echoes in the empty classrooms.”

“The blind spots continue to expand. Every day there’s something new you can no longer see, another shelf of memory claimed by everyday tasks.”

When Hill loses his vision, one of the things he’s most concerned about is that he won’t be able to drive, since in high school being able to get a girlfriend depends on driving. But this poignant note is leavened—as are many others—by Hill’s approachable tone and humor: “Another guy in school, who once sat by himself in the corner of the cafeteria and as far as you can tell has no friends at all, began dating the head majorette within weeks of obtaining his Mazda Miata.” When he and his mother go to Tokyo to procure a medication (and potential cure) not available in the U.S., his uncle, who has opened a travel agency, books them a flight from Charleston, West Virginia to Tokyo that involves four long layovers (Lexington, Kentucky; Chicago; Anchorage; and Seoul). “We weren’t surprised when my uncle’s travel agency folded after only a year,” he writes, with gentle humor.

Still, you’re never not aware when reading this book that Hill’s journey was long and often difficult. This, for example, when he remembers losing his vision:

“Next year, when most of your friends become acquaintances and acquaintances become strangers, you and Melvin will find yourselves killing time with each other in the library and office of your guidance counselor more days than not. Your two best friends will remain close, but you can no longer look for all the people with whom you used to sit in the library and cafeteria. After a month or two, they no longer look for you.”

It makes you glad for Hill that in the end, he makes peace with his blindness, finds love, and forges a successful career, to which this memoir is a testament.

Additional information

In addition to the print and digital copies of Blind Man’s Bluff, an unabridged audiobook, read by Curtis Armstrong, is available at Audible.

James Tate Hill is an editor for Monkeybicycle and contributing editor at Literary Hub, where he writes a monthly audiobooks column. The Best American Essays has chosen two of his works as “Notable,” and he won the Nilsen Literary Prize for a First Novel for Academy Gothic. Born in West Virginia, he lives in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Like James Tate Hill, the poet Stephen Kuusisto wrote a memoir about trying to pass as sighted for the first thirty-nine years of his life, which we write about here.