Folding Old Work into the New

February 13, 2016

An excerpt from The Vision & Art Project oral history with George Wardlaw.

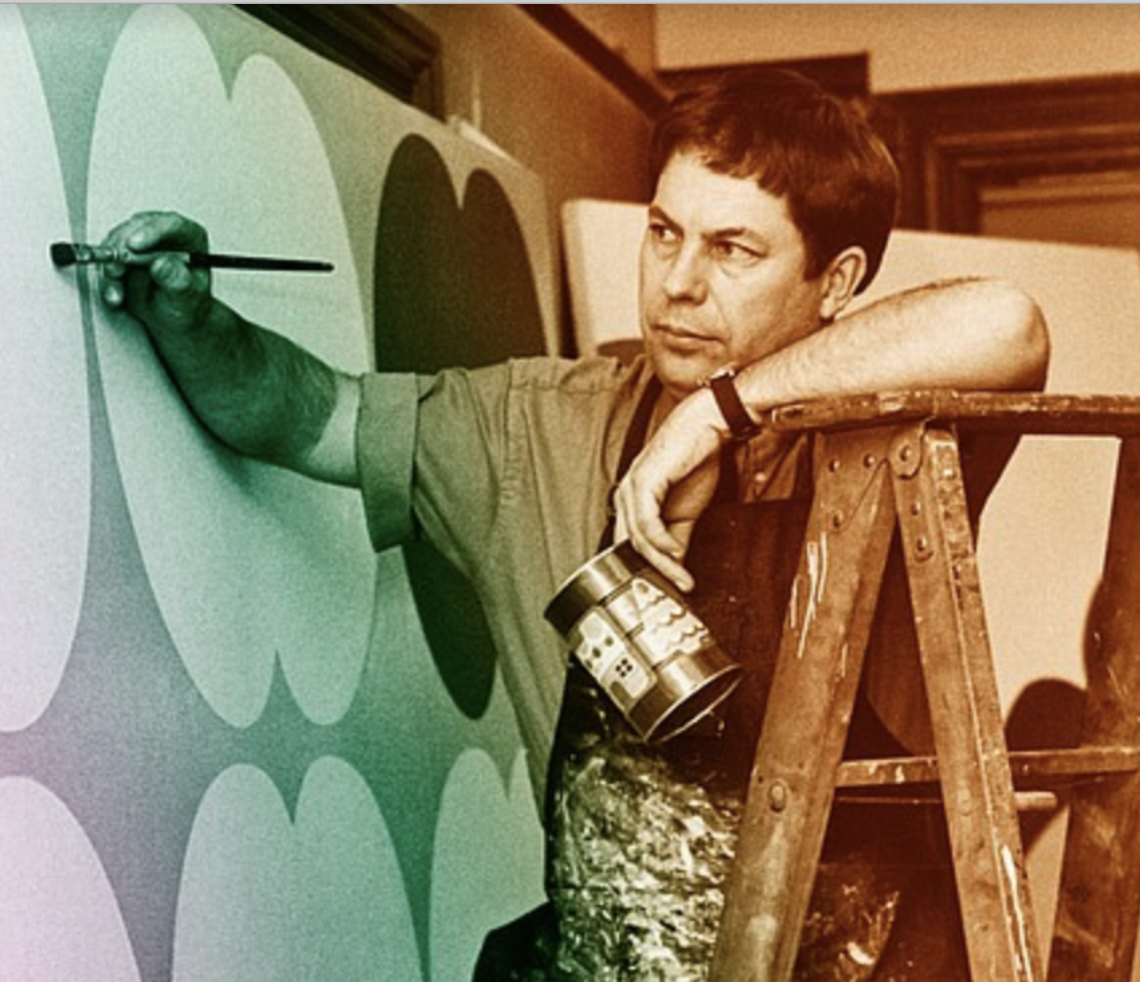

The Amherst, Massachusetts-based artist and educator, George Wardlaw, was born in Mississippi in 1927. During his long and distinguished career, he has turned to silversmithing, painting, and sculpture. One of the hallmarks of Wardlaw’s creative oeuvre is the dynamic way his artwork has evolved and changed over the years as he has pursued both spirituality and the spirit (read on for the difference) in art.

The past few years has brought attention to his work through the publication of a monograph, Crossing Borders (2012), a retrospective exhibition at the Mississippi Museum of Art (2015), and a video profile, George Wardlaw: Evolution of an Artist, which aired in late January 2016 on Mississippi Public Broadcasting. He recently received a grant from The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and, undeterred by macular degeneration, still works most days in his studio.

We visited Wardlaw at his studio on December 29, 2015, where he walked us through his life’s work, beginning with the exquisitely crafted jewelry from early in his career, finely finished exercises in formal composition, made of such materials as silver, enamel, ebony, and bone. Unassuming at first glance, these early pieces captivate and hold the viewer with their careful attention to the coming together of color, gesture and materiality. Each piece is conceived of as a whole—small sculptures that can be viewed in reverse or in the round. Turned in the hand, for instance, the backs of pendants reveal not the polished emptiness we might expect but alternative images.

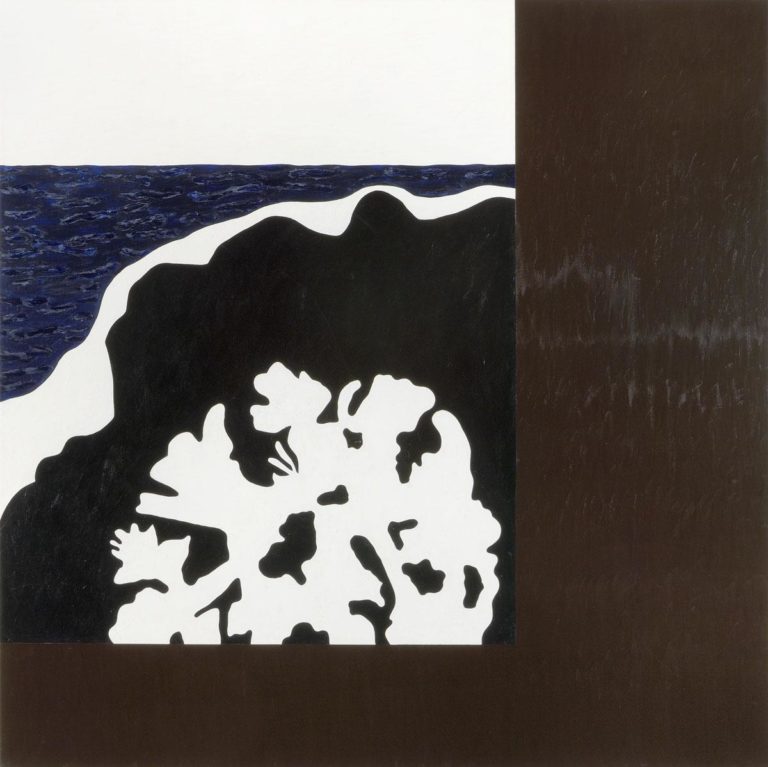

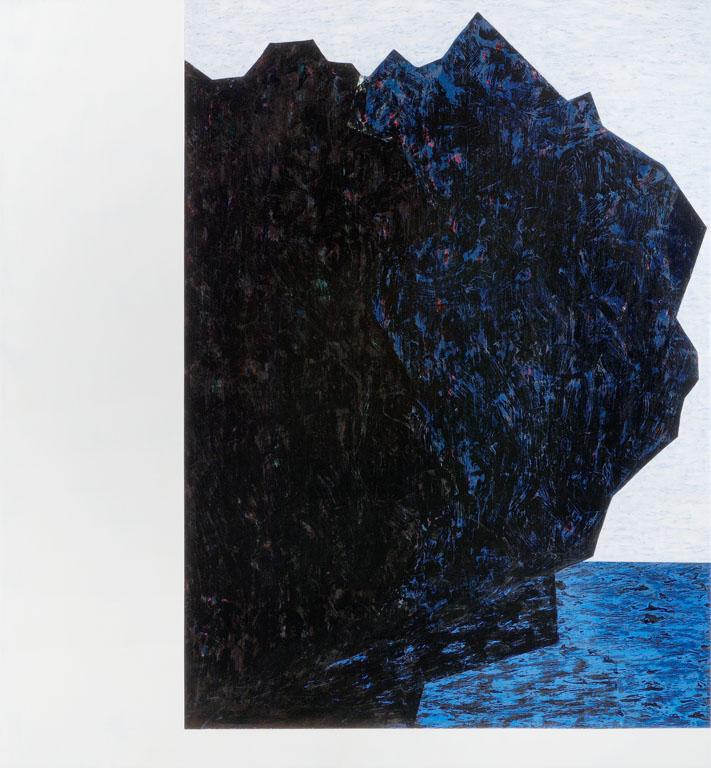

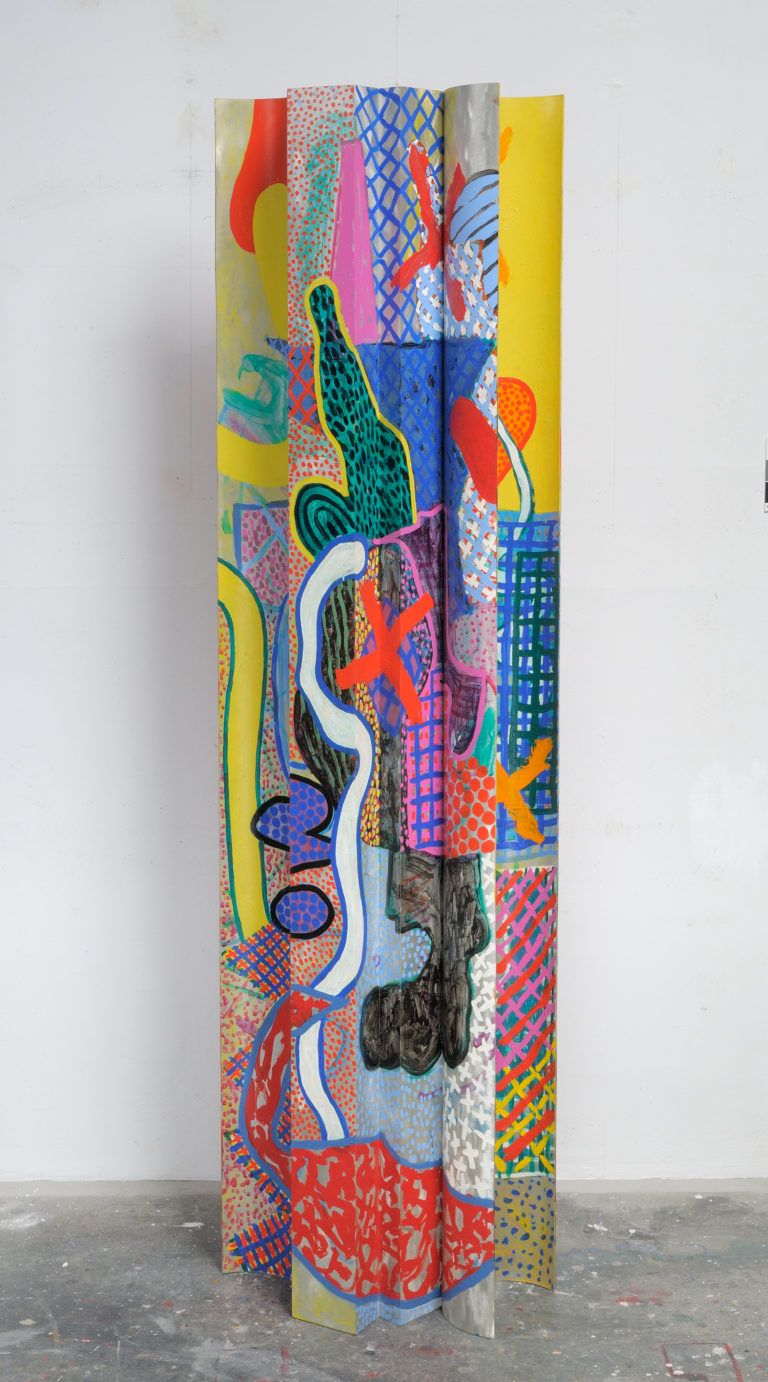

Wardlaw stopped making jewelry by the late 1950s, but in his maturity, he has come to feel that his jewelry was seminal, signaling the preoccupations and qualities that would distinguish his later paintings and sculptures. Most striking, perhaps, is to see the “reversibility” of his jewelry echoed in his most recent series of paintings, which depict canvases divided in two between complementary visual narratives.

To borrow Wardlaw’s own words, he has reached a point in his career where he is reinventing himself out of himself, turning to his vast library of images to more deeply understand and reflect on what he has created and how it’s been impacted by—and impacted—his cultural and spiritual heritage, his preoccupation with what it means to live in harmony within oneself and with others.

Oral History Excerpt: George Wardlaw

Spirituality and spirit in art

Phillips / Schumacher (V&AP): When did your interest in art and spirituality begin?

Wardlaw: I wrote my thesis for an English course on Kandinsky’s book, Concerning the Spiritual in Art. And once Ben Bishop, the teacher I’ve spoken of before, approached me in class from the back. He looked at my painting and said, “Wow George, that’s terrific. That belongs in a museum of nonobjective art in New York.” And then he said, “I have a name for that painting. It should be called Spiritual Journey.

That encounter, along with Kandinsky, put me on the road to spiritualism in my work. Spirituality played a big role in my work over the years. It is not playing a particular role in, at least I think, in my current work. I think spirit is playing much more of a role.

V&AP: What is the difference between spirit and spirituality?

Wardlaw: Spirit and spiritualism, spirituality, have common grounds. But spirituality is more religious-based than, just say, spirit is. I think spirit is broader. And so I’m trying to make my paintings have spirit to them. An uplifting physical quality as opposed to a mental quality. Spiritualism is more directed toward the heart, I think. The so-called soul.

Bringing past and present together

V&AP: What are you working on now?

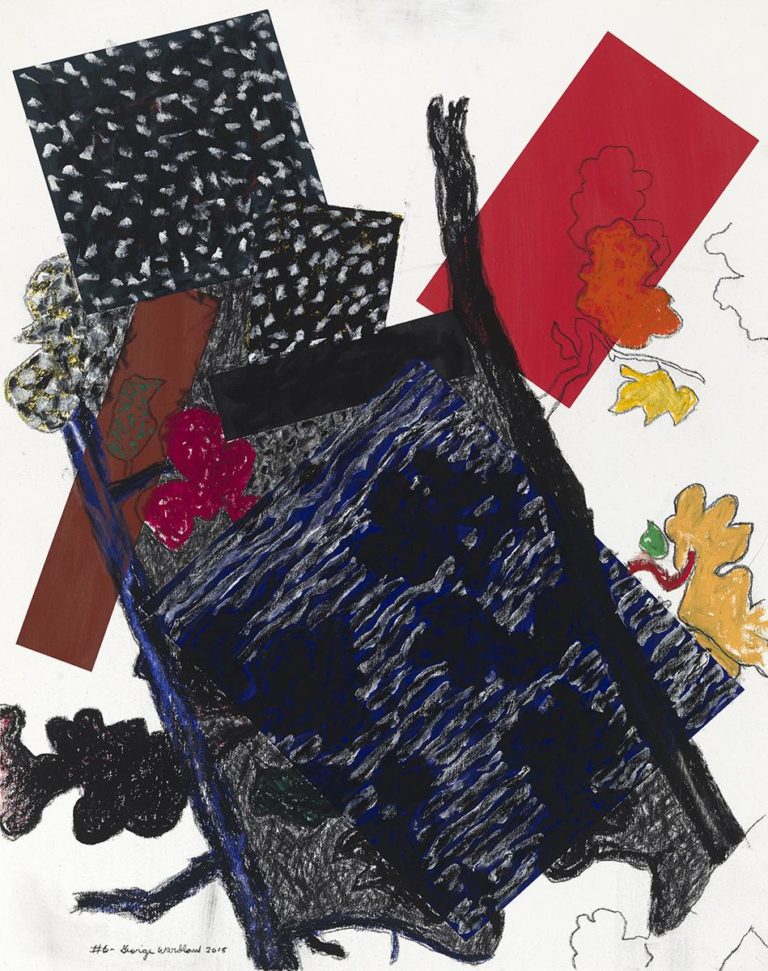

Wardlaw: My current work involves going back to my previous work—or library, as I think of it—and picking up parts of it. I’m excited about the potential of bringing my past and present together, using my own unique visual vocabulary—mined from my previous works.

I‘ll go down to my studio with my camera and I’ll photograph my paintings from various angles. I’ll photograph the work from over here; I’ll photograph it from over there, low and high, to see it differently. Then I download the photographs to my computer—I never thought in my life that I would ever do this—and combine the images, and then I photograph those images from the computer screen. From the fifty or more images that I’ve developed, I decide on one and project it onto the canvas, knowing that I’m not going to copy what I’m projecting. Rather, I’m going to use it as a starting point.

When I first set to work, I’m not too excited about it. At some point I say, “Oh wow that’s kind of exciting.” It’s then that the painting begins to develop. It is not in the photographing of it; that’s part of it. It’s not in the computer; that’s part of it. It is not in the projector; that’s part of it. It’s actually the painting process that is the exciting part.

V&AP: Why are you going back to your previous work and juxtaposing images you did in different styles and at different points in your career in opposing pairs?

Wardlaw: Part of my reason for bringing these different works and vocabularies together is to contrast them. I am not yet sure myself where I’m going with this most recent body of paintings and am reluctant to nail it down at this point because I want the process, the evolution of the painting, to determine whether it is valid, whether it is as exciting as I think it will be.

When I did that painting, Connections, I questioned whether or not I should do it in the first place, working with geometric forms on the left side of the painting and an image of an apple tree on the right. I said to myself, “If I don’t do it, I’ll never know.” When I started to do this particular group of works, which I am calling the Evolution-Spirit series, I wanted to do something that was exciting visually, that was exciting in terms of spirit. I was thinking that I wanted to make work that was equal in spirit to Matisse’s late work [the paper cutouts]. That’s a big undertaking.

In doing it, I have come to realize there is another subject matter in the work, that of differences in our culture, of people working together, living together, cooperating. I have yet to decide if there is a conflict between that and the spirit that I want the work to have. I will have to find the answer to that question in the process of working.

V&AP: In your current work you talk about working within and drawing material up from your life’s experience and from your past work. As you’re taking these earlier works and bringing them together and recombining them, are you also seeing your life and your feelings in a kind of retrospective way?

Wardlaw: I don’t know for sure and I’m not ready to nail it down. When I am looking at my old work, I am trying to find out how I can use it. I’m not evaluating it, nor am I necessarily appreciating it.

The spirit of Matisse and Kandinsky

V&AP: You mention the influence of Matisse. Can you talk more about that?

Wardlaw: The first time I saw Matisse’s work, the cutouts, at the Museum of Modern Art in 1961, I thought they were hard edge, geometric paintings. I went to see them a few years later in Washington, and they were the same paintings but not the same paintings. I saw all the cut marks, I saw all the staples, I saw the working process and originally I had seen only the color and the hard edges because of the kind of work I was planning at that time. I didn’t see the work for what it was. Matisse is my hero and I would like to try to do something that is equivalent to the spirit of Matisse but is George Wardlaw.

V&AP: Have any other painters had a major influence on you and your work?

Wardlaw: Over the span of my career, Kandinsky was more of an influence. But mainly in painting.

Starting and finishing a painting

V&AP: Do you think of your painting process as having a beginning, a middle, and an end?

Wardlaw: With my current work, once I project it onto the canvas, I draw on it, sometimes with charcoal, sometimes with pencil or a mixture of the two depending on the container that I’m working with. And then I start to paint and actually that is the most difficult part of the process, where you start. Often it is, “Well, I’ll start with this color or I’ll start with that color.” It’s not until the painting starts the conversation with me that I get excited about it and begin to know how to follow the painting. In the beginning, I don’t know how and it’s discovered in the process.

V&AP: I know this question is asked a lot, but how do you know when you’re done?

Wardlaw: If my son were down here, he would say, he doesn’t know. I’ll come upstairs and I’ll say, Well it’s done, and Steven will say, Are you sure? I think so. Well, let’s wait until tomorrow. I’ll come back tomorrow. Hmmm. Maybe I could work on that a little more. A painting very often is finished three or four times before it’s finished. In a way a painting is never finished. You just stop working on that one and go to the next one and the next one. Hopefully, they’re never finished. I said to Stephen the other day, I never hope to do my masterpiece because if I do maybe I will lose the drive. I think the most important thing that an artist can have is drive. You really want to find out what’s on the other side and hope that you don’t find it because if you find it, it may end the trail. That’s kind of my attitude about finished work.

You really want to find out what’s on the other side and hope that you don’t find it because if you find it, it may end the trail.

George Wardlaw

V&AP: When you sit down to work on a painting that is not finished, how do you commence?

Wardlaw: The key phrase is when I sit down, and I do sit down. Where I might start depends to some degree on how long I’ve been away from the painting. Usually, not more than one night will have passed.

I am a deep believer in what I think is a fact, that although you are sleeping, your brain goes on working, including on the paintings (or whatever) you were doing the day before. So when you come in the morning and take a fresh look at your work, it has changed because the brain changed it overnight. The last thing I do before I go to bed at night is go to the studio and look at the work because I want that new image in my head. Often a painting that I thought was something rare like “eggs laid by a tiger”—that’s a quote from Dylan Thomas—when I left, no longer appears so in the morning.

So I sit and look. This reminds me of Jack Tworkov. It was always said about him that he stared a painting to death, because he looked at it so much. He sat and looked and sat and looked.

You sit and look and contemplate and you talk to yourself and the painting talks to you. It’s a back and forth situation, and it’s when the painting begins to take over the conversation that it gets really exciting, that interaction between the painting and the painter. And you wait for the message. “Okay, you need to change that color or you need to change that shape or something.” And you do it and that sets the work in motion again. It renews the painting. If you thought it was finished, you realize it obviously wasn’t.

Setting a painting in motion

V&AP: Setting the painting in motion… Can you say more about that?

Wardlaw: The painter Lester Johnson, a colleague of mine at Yale and a close friend, used to say that when he got really stuck with a painting, he’d load up the brush, put it behind his back, walk over to the painting and turn his back to the painting, and then blindly paint on it. This would set the painting in motion again. Not by looking at the painting, but by just destroying something arbitrarily, the painting was set in motion again. Well, I don’t do that, but I do set my work in motion sometimes by arbitrarily changing something, maybe by smearing a line or painting over an image—anything to disrupt the finished appearance of the work when I’m not satisfied with it. At that point, any disruption is fair game.

V&AP: When you work, are you consciously looking for an opportunity to expand or are you looking for closure?

Wardlaw: I’m always looking for a means to expand because I am still learning. I learn something every day that I come to the studio, and if that were not true, I must be dead.

“Color is very important”

V&AP: Can you talk about how you approach color in your paintings?

Wardlaw: I think color is very important. It is one of the most expressive things that one uses in one’s art. For me, color is greatly affected by place and environment.

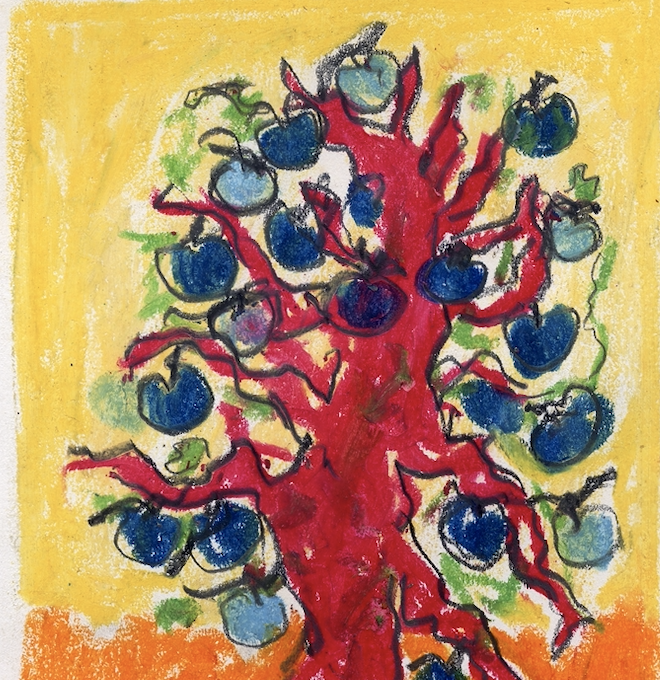

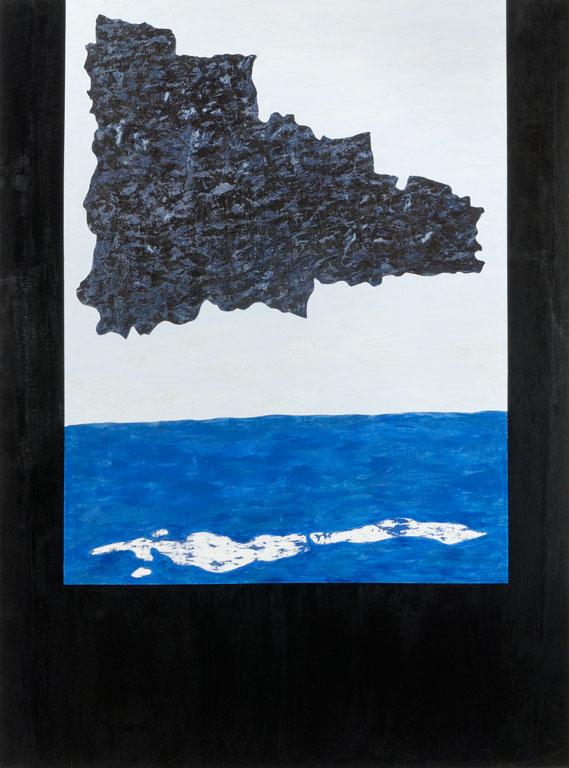

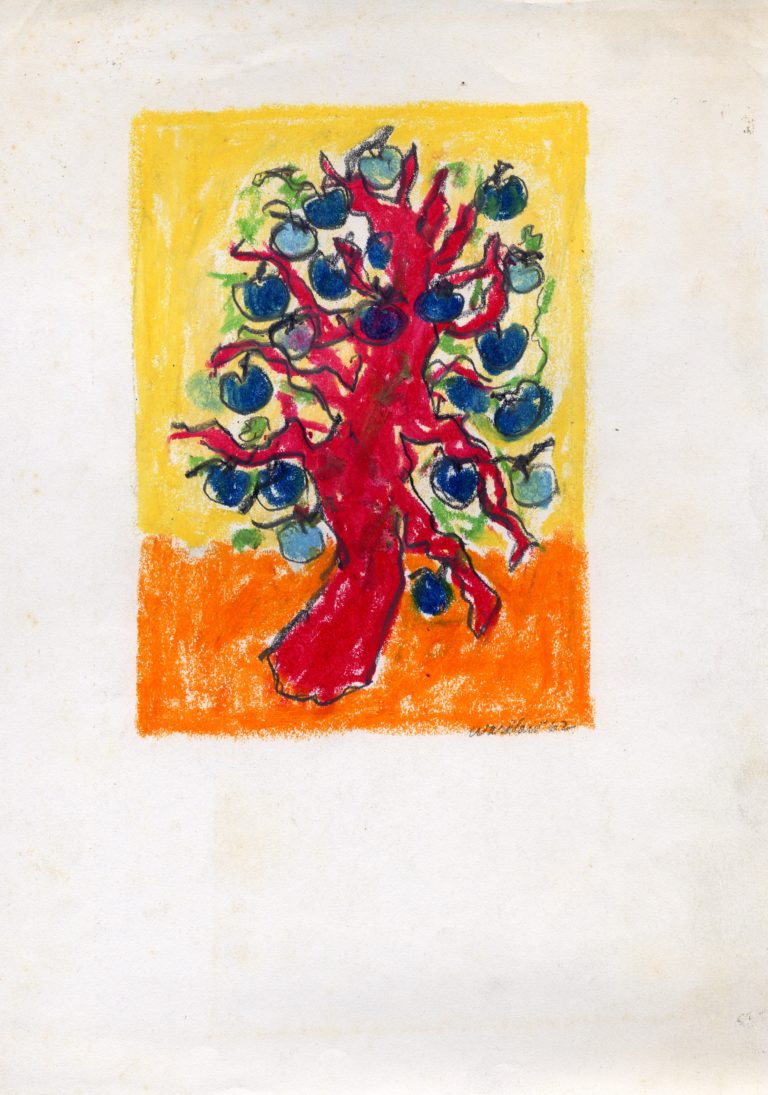

In 1955, when I moved to Louisiana, bayou country, my paintings became a different color because place always affects my work. The same was true when I moved to New Paltz, New York, and bought a house on a hill that looked down into the valley and up into the mountains. There was a river down below, and the days were often foggy. Whereas in Louisiana, my paintings became more muted in color and less expressive, at first in New Paltz my work became gray. I was painting landscapes in my studio at the time, not from direct observation, but, still, I looked out the picture window all day long, and my paintings were influenced by the grayness outside. As a result of something that was said to me about my work at the time, my work changed. I became more aware of color and more intentional, more conscious in my use of it. The first series that showed that was my apple paintings, which eventually turned out to be containers for flat color.

When I think about my current interest in making paintings about spirit, I think color will be the primary force. Matisse’s paper cutouts are an excellent example. I don’t yet know for sure what container—shape and forms—the color’s going to be in, but I know it’s going to be about color because that is to my way of thinking the best means of dealing with exuberant spirit.

V&AP: What was said to you in New Paltz that caused you to change direction with color and start your apple series?

Wardlaw: It’s interesting to me to notice how things that are said affect me and my work. The reason I left the gray paintings I was doing in New Paltz was because of something almost incidental that was said to me. The artist Paul Burlin, who was in his early eighties at the time, came to SUNY New Paltz to teach for a semester. He and I became close friends. He would come to my house and have dinner every Monday night and, along with watching boxing matches on TV, he would look at my paintings.

After looking at my gray paintings , he asked, “What are you trying to do?” And wow, that hit me mighty hard. What are you trying to do? I took that to mean he didn’t know. And I didn’t have an answer for him. I thought about it and talked to myself, “Well, okay, I don’t really know. As a result of that discussion, I stopped painting for six months, until one day when I was riding in the back seat of a car and was kind of nodding off to sleep. All of a sudden, I woke up and said, “Now I know what I want to paint. I want to paint an apple.” That started what was to become my Apple series, which I worked on for thirteen years.

Over these past few years, my son would often talk to me about my work, but he has gradually stopped doing so. I haven’t asked him why, because I think I know why—he doesn’t want to lead me. He knows that I might take something he says about the work too seriously, and possibly modify the work.

A fear of being too consistent

V&AP: Over the years of painting, you’ve been inventing yourself out of yourself and working in many different mediums, in a lot of different ways. Have you noticed any consistencies in either your working methods or in your work itself?

Wardlaw: There is a consistency in my work and an inconsistency in my work. The way I work, that is going to happen, and sometimes, as I’ve said before, I get on the wrong track. But sometimes when I get on the wrong track and I keep it. I get back on track and it becomes part of another series.

I periodically do paintings that are misfits. They aren’t “bad” paintings, but failures in terms of consistent development. I personally have a fear of being too consistent. I feel some artists are too damn consistent. When my mother was alive, I used to tell her I had to go to the studio and work. She would say, “George, you have a studio full of work. You don’t need any more.” She never understood what made me tick. She was always proud of me and my accomplishments, but had no understanding about the drive creative people have to continue evolving.

“I didn’t really know what macular degeneration was”

V&AP: We came to be in touch with you because you were recently diagnosed with macular degeneration. How does being a mature artist put pressure on you to work in certain kinds of ways that you didn’t work before? In asking this, we’re not expecting or thinking that it’s all about limitations and things becoming more diminished as you get older. What we’re interested in talking about, rather, is the way the body is involved in art and the body has, creates, certain possibilities as a result of that.

Wardlaw: That’s definitely true.

V&AP: When were you diagnosed with macular degeneration?

Wardlaw: I was diagnosed about two years ago and when I was told what my problem was, I didn’t really know what macular degeneration was. I think I’m doing as much as I can about it at this point. I use a lot of eye drops. I use a good bit of ointment, particularly in my left eye. I take vitamins regularly. I see the doctor regularly. And how it affects me is I’d say more in close up. It affects me in reading. My eyes get very tired. I don’t read as much as I used to. My use of the computer and painting doesn’t bother me as much as reading does. The last exam that I had, the doctor said, it hasn’t changed since the last one before.

V&AP: Are you making any plans or do you have any anxieties as you think ahead to what might happen if the vision does worsen?

Wardlaw: Naturally I think about it. I am such an optimist. I generally look on the positive side of everything and don’t think about it too much, except when my eyes get tired. I know they’re not going to improve. I’m aware they’re going to get worse. But it’s slow developing. Hopefully I’ll get through and will not be affected. That’s my optimism.

V&AP: What are the advantages and disadvantages of being a mature painter?

Wardlaw: Speaking for myself, I have a better vocabulary now. I have more to draw on. I think that is the reason that older artists, if they continue to work, do their best work when they’re older. I think of the fact that Matisse came up with some of his best work after his illness [intestinal cancer], when he had to find a new means to develop his work. I was recently reading about Ellsworth Kelly, who in his later years said he couldn’t paint as big anymore.

V&AP: Our work with the Vision in Art Projects aims to look at the subject of sight and what it means to see. This is a vast subject, as you know. What does “seeing well” mean to you?

Wardlaw: Sight to the optometrist is different from what sight is to an artist. Sight to the eye doctor is about the physical part of seeing. It’s about measuring, about seeing if everything is working together to give you 20/20 vision. But there is a difference between the physiological process of sight and seeing in the way an artist—and many other people—see. It’s good to have 20/20 vision, but you really see with the brain. In fact, I would say that it is the brain that gives sight, and life experiences that give vision.

You can find a transcript of our complete oral history here.

To see George Wardlaw: Evolution of an Artist, which aired in late January 2016 on Mississippi Public Broadcasting visit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XtzEhF8etzg

Leave a Comment