Wolf Kahn at the Brattleboro Museum: The Surface & What Lies Beneath

October 01, 2017

Wolf Kahn: Density and Transparency at the Brattleboro Museum and Art Center exhibits the artist’s post-macular work and reveals his greatest strengths.

Wolf Kahn’s paintings have long garnered serious critical attention and an audience of admiring viewers. Largely known as a colorist who brings his luminous sensibility to landscape, Kahn also engages in a sophisticated conversation with the work of other artists. Kahn’s most recent paintings, on view at the Brattleboro Museum and Art Center through October 8, 2017—all completed within the past ten years since his vision has been affected by macular degeneration—openly display an emotionally profound vision as never before. They show the depth, risk-taking, and complexity that have always animated Kahn’s work.

Pushing preconceptions to the margins

Kahn has spoken in the past about how important it is for a painter not to hold back, to work enthusiastically without resorting to “predigested” perceptions. In 2007, in the journal Art in America, he wrote:

I generally mistrust any advance “feelings” that I am trying to express in my work; for me, it is preferable to have new emotions emerge in the process of doing the work. It is difficult enough to stay clear of conventional feelings. In choosing a subject, a place to set up in the landscape, there is much that is unanalyzable. Prior attitudes only get in the way. To a large extent one’s history gets in the way, as well as one’s previous work. As artists, we wish to be reborn with each situation… to [cleanse] the eye and [push] preconceptions to the margins.

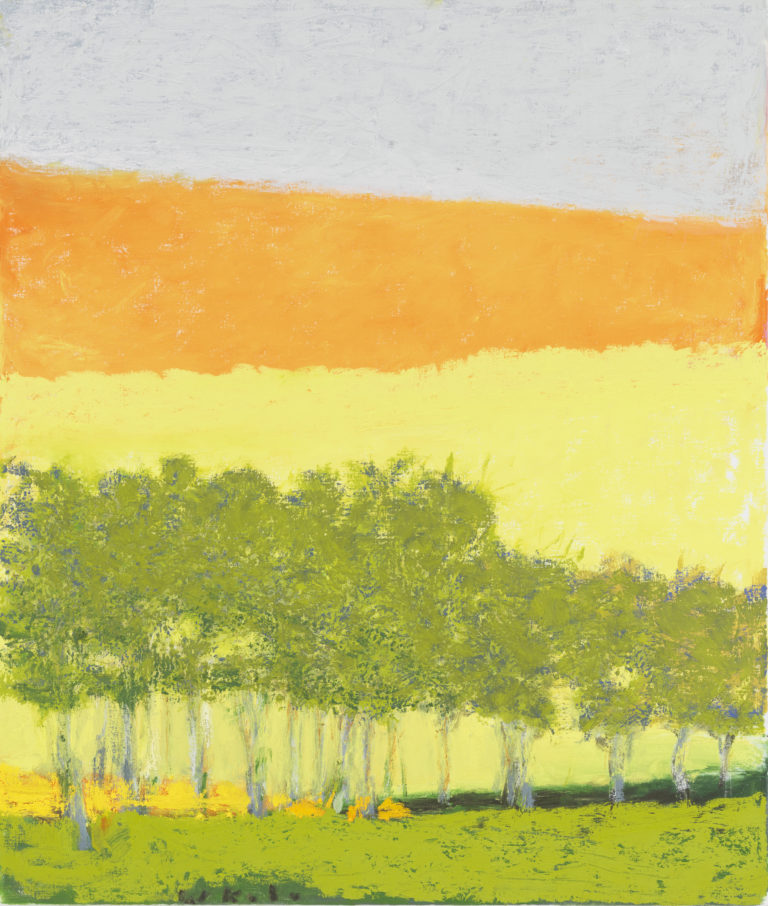

The work exhibited in Density and Transparency exemplify this guiding principle. A yellow stripe of vivid translucence transverses a canvas between dense crimson masses; a tangle of pale inscriptions branch out in vivid, mute chatter against a pink background; chromatic gray forms have clustered in upon a warm, colorful background. The paintings juxtapose counterbalanced elements—chaos and rest, color and tone, representation and abstraction—so as to allow the viewer to see and feel the work as an interconnected whole. It is visibly concerned with the active tension of wholeness.

Taking risks

Of all the paintings on display, perhaps most striking in its risk-taking is Counterpoint. The painting’s surface and what lies beneath move in relation to one another, giving rise to a variety of expressive modalities and interpretations. In the larger context of Kahn’s work and in the hint of landscape afforded by a horizon line, the viewer is encouraged to see in the background a field, in autumn perhaps. At the same time, however, other elements of the background, such as the “sky,” almost eerily pale, and a chromatic gray clump of what might be distant foliage, push the viewer to consider the background as something other than the literal representation of a scene—i.e. to see it as an abstraction, or to see in it the painter’s formal, even human, concerns.

The painting’s surface layer, on the other hand, appears more abstract, with chromatic gray masses, intruding between our gaze and what lies beneath. Some of the masses are semitransparent, with chroma from beneath shining through, but the overall feeling, at least at first, is that the gray masses are a kind of fog that has drifted over and obscured the painting’s underlying image. Yet, mirroring what is going on in the background, the viewer is encouraged to see the possibility of representation in the foreground, the gray shapes somewhat reminiscent of leaves and the ghostly web of white marks of stalks or trunks.

Surface “fogs”

Kahn has used this technique of surface “fogs” in the past to create effects of foreground, evanescence, of something from the lower layers of the painting glinting through, of broken glimpses. In Counterpoint, amid the symphony of other decisions Kahn has made, the effect is pushed to such a degree that the world he represents takes on motion. That which is background now becomes foreground, then recedes; that which is abstract becomes representational, that which is representational becomes abstract; the painting acquires a life force known only in those works of art from deep in the well of painting, where mystery intersects with perception and technique.

Innovation and convention

Counterpoint announces itself as a painting that has taken risks, but even Broken Birch in Broken Woods, at first glance a far more conventional painting, is highly innovative, with a power that derives from something other than the simple representation of trees. In Broken Birch, the singular moments of color placement, from the saturated green in the lower bottom left hand corner to the snugly placed note of vivid blue in the upper left-hand quadrant, to the violet and diaphanous gray on the right, seem unquestionably right and reveal Kahn’s ability to push the art of painting to a place few artists go—to a place perhaps few can.

Whether Kahn (or the viewer) has seen these colors in the field is immaterial, since what Khan accomplishes here is to make color do what color and nothing else can: suggest vast amounts of complexity in the natural world with just a brushstroke. At the same time, a layered calligraphy of linework dances and whirls on both the surface and within the depths of the painting, pulling the viewer into a space where small fires seem to burn. The sweep of neutral grays through the middle of the canvas, the darker trees, the shards of color flying about, impart a dark, ominous, even apocalyptic tone. Is it possible this painting is an homage to the end of forests Kahn knows well? A protest against the environmental calamities he foresees or fears? While viewers may ultimately not know the answer to this question, they do unquestionably sense in this painting Kahn’s emotional and intellectual investment in the world we inhabit.

Kahn’s long career as both a painter and writer reveals his insight and thoughtfulness. His readings of other people’s paintings; his readings of events such as Hurricane Katrina, which he wrote about in 2007; his readings of the visible world as presented in his paintings, all reveal that he looks carefully and contemplates what he sees. It should thus be no surprise to find such a depth of thought and response in this work.

Macular degeneration and Kahn’s evolving style

Though it’s not clear what role Kahn’s eyesight plays in the changes we see in his work, Mara Williams, chief curator of the Brattleboro exhibit, explains in the wall text that, since Kahn’s vision was affected by macular degeneration, he has experimented with his working methods. While Kahn still builds up his compositions with multiple layers of thinned paint, his approach to the top layers has changed, she notes, and in place of “scratchy brush strokes” he now uses oil sticks to produce “bold forms and fields of densely saturated color.”

While this technique may account for some of the startling new effects in these paintings, it is the astounding visual acuity and emotional range of the artist—his enormous experience and confidence, felt in every decision he makes, many of them surprising—that gives these works their intense power. Kahn’s most recent paintings exude the confidence of a master who has discovered much about painting over his decades of work, perhaps most markedly that its mysteries and possibilities depend not upon representation or abstraction but on the ability of an artist.

Many years ago, in writing about Milton Avery, Kahn noted that “[Avery is an] example of a modern painter who has undergone, in the development of his work, a consistent change toward greater power and greater depth.” Density and Transparency shows that Kahn, too, has undergone such a development.

Comments

Stunning paintings….. stunning article! Thank you.

These paintings express a strong energy and creativity that is fresh and alive.

I saw Kahn’s art for the first time in the 1990’s in The Boca Raton Art Museum. The lasting impression of the color intensity and size of the the art was memorable. Every year that I have taught art to children, Wolf Kahn’s art has made its way into my classroom. I am compelled to know more about artist who paint with low sight as I have young students with this challenge.

Leave a Comment