Painting as Poetry

July 09, 2016

A Memorial Exhibition at RISD’s ISB Gallery highlights Thomas Sgouros’s transcendent vision and the dramatic paintings he did after experiencing severe vision loss due to macular degeneration.

We recently went to see Thomas Sgouros’s (1927–2012) paintings at RISD’s ISB Gallery. It’s the first time Sgouros’s paintings have been exhibited since 2013.

Stepping into the gallery was a sensory experience. Outside, the light of the bright summer day was hard and democratic. Or so it seemed in relationship to the tender and diffuse light in RISD’s ISB Gallery, lit in part by Sgouros’s canvases, whose deepest subject is perhaps the spirit.

This is true both of the meticulous still lifes and scenes of Rome Sgouros did when fully sighted and the Remembered Landscapes, as he called them, which he created after losing his sight at the age of 65 to macular degeneration.

While the paintings Sgouros did before he experienced vision loss look distinctly different from the paintings he did after, they are at bottom profoundly similar. This has to do with the constancy of the artist’s deepest objectives. Once he was legally blind, Sgouros discovered that he could take what he had learned about painting in the first part of his career and use it to create work that has, despite its surface appearance, an underlying sameness of intent. Sgouros put it this way: as he came to realize, his mission had never been to paint what he saw, per se, but to “energize, explore and change the equation of the rectangle.” This realization allowed him to gain his bearings and paint a new body of extraordinary work after what was for him a devastating diagnosis.

RISD ISB Gallery honors Sgouros’s multi-faceted career at RISD

Sgouros was raised in Chicago and Cambridge, Massachusetts, by Greek-American parents. He received his BFA in illustration from RISD in 1950. After working as a professional illustrator in Boston and New York, he returned to RISD in 1962 to teach in the illustration department and invest himself in his studio practice as an artist.

Over the next forty years, Sgouros went on to become a beloved teacher and leader at RISD. He is generally seen as responsible for the ongoing ethos of the illustration department. The curriculum he developed is still being taught; the faculty he hired now lead the department; the students he mentored have matured into prominent artists and illustrators and dedicated work to him, including Chris Van Allsburg and David Macaulay. Among many other recognitions Sgouros received during his time at RISD, he held the Helen M. Danforth Distinguished Professorship from 1991-1994 and was a professor emeritus at the time of his death.

In honor of his service, the illustration department reserved the inaugural exhibition in the newly renovated ISB Gallery for him. David Porter, an associate professor in the department who was himself hired by Sgouros and became a close friend, curated the show. Porter selected the 49 works on display from paintings held by Cade Tompkins Projects as part of the artist’s estate. Aside from a handful of works from Sgouros’s early career as a professional illustrator, Porter chose watercolors, oils, and pastels that were “redolent of Tom,” as he said, “works that had a spiritual aspect to them.” In keeping with the theme and intimacy of the exhibition, the wall text included reminiscences from 10 people who knew Sgouros during his time at RISD.

The first part of Sgouros’s career, before macular degeneration: still life paintings and the “riddle of the rectangle”

In the still lifes to which Sgouros devoted himself in the first part of his career, he tended to paint in extensive iteration a handful of objects that held special resonance for him. Included among his favorite subjects were a postcard of a Degas painting; a vinegar and oil jar given to him on the occasion of his first marriage; a bicycle horn that had belonged to his son; Prip silver smithed by a colleague at RISD. He didn’t return repeatedly to these subjects in an effort to capture the “anecdote,” as he sometimes called it. He returned to them rather in an attempt to solve what he termed “the riddle of the rectangle,” which involved coordinating idea, shape, value, color, space, rhythm, and contrast in an interpretation of what he saw and felt.

Thus, though Sgouros worked from life before going blind, it wasn’t with the intent of copying nature. He was instead focused on “organiz[ing] nature’s elements—shape, color and mass—to create a poetic statement which transcend[ed] the material.” The resulting still lifes emanate, as do those of one of his favorite artists, Giorgio Morandi, a sense of infinite mystery. Looking at them, you sense realities hidden within, or beyond, the material.

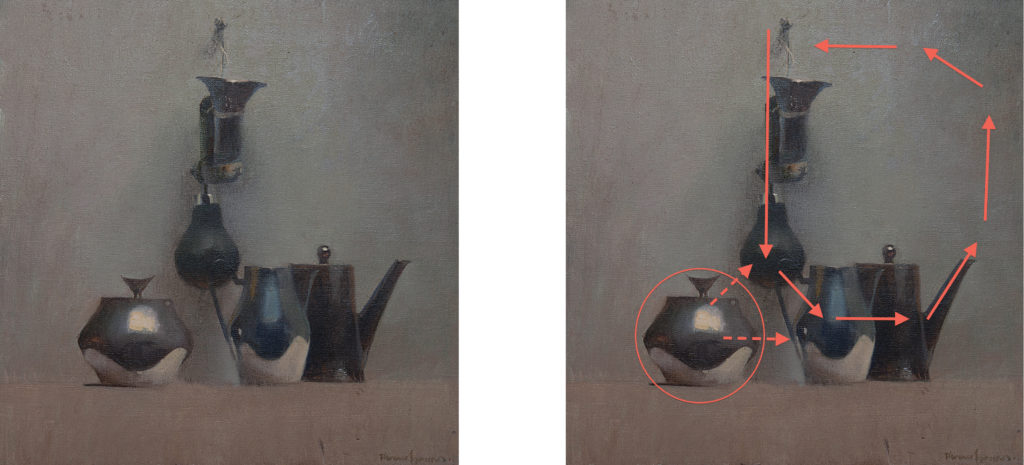

Prip Silver with Horn

In one of the still lifes in the exhibit, for example, Prip Silver with Horn (1990), it can be clearly seen that Sgouros is organizing the canvas (“the riddle of the rectangle”) intentionally and graphically to effect. It is not an accident that the black ball of the horn provides a focal point to the canvas, just off center, and that the handle of the Prip silver piece second to the right visually elides with the ball, drawing the viewer’s eye to the artist’s chosen focal point, then directing it right, from the viewer’s perspective, up along the sharp geometry of the kettle spout. The eye is kept on the canvas by a soft compression of values, only slightly darker along the edge, up and over, returning left to the flute of the horn, then back down to the ball.

Carefully composing the objects with an eye toward the Gestalt law of proximity (where objects in close proximity appear to form groups), the Prip vessel to the left is at once isolated and separated, balanced, inviting the eye to jump back and forth from horn to vessel and neighboring vessel and back. This is but one of the many subtle, intentional, and masterful compositional moves that comprise the language of painting and allows an artist to express the feeling and experience of a thing.

As he comes into his own as a painter, sudden, severe macular degeneration devastates Sgouros

In 1992, just after Sgouros had completed and exhibited 84 still life paintings, macular degeneration devastated the vision in both his eyes. Within six months, he went from being fully sighted to legally blind. This is a more rapid progression than is often the case. He had no time to prepare himself, psychologically and otherwise, for the impact of the disease on his life and art. At the same time, his first wife, Joan Sgouros, was dying of cancer.

Though he had a long career behind him, he felt he had only just come into his own as a painter. He couldn’t imagine a life without painting. But he couldn’t conceive of how to continue with the little vision he had left. As he discusses in a 1994 article in the Providence Journal, in his darkest moments, he struggled with feeling that he had come to the “end of his life.” He says he even, quite literally, considered jumping off a bridge. Instead, he continued teaching at RISD and going to his studio every day. As he explained many years later:

I had to work and I didn’t know quite what to do, so I started making paintings. I had no idea what I would be doing. I couldn’t examine anything based on observation, which turned out to be a pretty good thing, because I don’t think an artist should be a reporter of observation [but] rather something a little more profound.

Masking tape, a T-square, remembered landscapes

He used masking tape and a T-square to create horizon lines and then began painting the Remembered Landscapes that would constitute the sole subject of his work for the last 20 years of his life.

The first ones were small, tentative, nearly monochromatic—as opposed to the large, roiling, wildly chromatic landscapes he would eventually undertake. What he was referring to when he called them Remembered Landscapes is not entirely clear. On the one hand the term suggests, rather poignantly, that he was painting the memory in his mind’s eye of what he had once seen on the horizon.

But they are “remembered landscapes” too in that, aided by books, he was thinking of and implementing in his own work the strategies other painters had used. In a 1988 Watercolor Magazine article, for example, Sgouros had observed how J. M. W. Turner gave one of his paintings power and vitality by putting bright orange in the trees above the horizon. How Winslow Homer used a heavy dark value in the background and a warm value in the foreground to create deep space. Sgouros adopted these strategies to similar, magnificent effect in his Remembered Landscapes.

And, finally, Sgouros’s landscapes are “remembered” in the sense that he relied on his memorized palette and artistic muscle memory as he worked.

“In many ways they are abstractions”

In moving from the work before his vision loss to his work afterward, we see echoes, especially with regard to the presence of horizon lines and reflections. In Prip Silver, a subtle but pictorially essential horizon line strikes across the canvas in line with the base of the vessels. This line is rendered not with line or contrast but through a delicately organized shift from cool to warm. We need only look across our desk or table to see the visual impossibility of such a horizon line directly under an object. By virtue of the principles of perspective, horizon lines are always beyond and behind the subjects we behold.

Yet Sgouros deftly defies this perceptual truth and imparts an overt fiction upon his canvas, a line that is at once both graphic and spatial, thus rendering his painting not representational but something else altogether. In his Remembered Landscapes, he works in a similar fashion. He draws from his lifelong habit of combining careful observation with abstraction and suggestion. Miasmas of color become emotionally laden evocations of scenes we have seen. The sky at dusk or as a storm gathers. A salt marsh reflecting clouds. The horizon we gaze toward in a moment of repose. As Sgouros once said of these works: “In many ways they are abstractions. Shape relationships, color relationships, texture relationships that happen to be in the context of what could be landscapes.”

“Huge paintings he worked on with his face to the canvas”

In the 1994 profile of Sgouros in the Providence Journal, Sgouros says he worries that his story will be “poignant.” Or, worse, that he will come off as an inspiration to others. But, though he apparently didn’t want it to be so, Sgouros—whose commitment, rigor, and kindness made him an inspiration before macular degeneration—became an even greater one after vision loss. How could it be otherwise? After experiencing an unimaginable loss, he adapted. Next to the meticulous still lifes from the first half of his career, Sgouros’s Remembered Landscapes are breathtaking. Their scale, their poetic resonance, speak of blindness having transformed the artist’s vision from something small to something grand.

As a teacher, too, macular degeneration only seemed to have increased Sgouros’s power. Many of the students he taught in his later years say he offered tremendous insight despite (or perhaps because of) his failing vision. One of his students, David Slonim, who took Sgouros’s watercolor class before his vision loss, sought him out many years later when he was going through a difficult transition in his own work. He met Sgouros in his studio, where he was working on a Remembered Landscape. Slonim is still moved by the memory of watching him paint:

Here’s what I remember. He was very open and humble. He went through my whole portfolio. His eye an inch from the pictures, he told me a good painting is a visual arrangement that speaks to us because of the visual arrangement, not because of the thing being depicted. This was a man who was going blind, surrounded by canvasses, huge paintings he had worked on with his face to the canvas, only able to see a few inches at a time.

Slonim says the visit had an immediate, salutary effect on his work.

“The deep blue air, that shows nothing, and is nowhere, and is endless”

David Porter, the show’s curator, says that when you look at a Sgouros painting, you are taken past the painting. The landscape is disappearing. For him, the effect calls to mind the final stanza of Philip Larkin’s poem, “High Windows:”

Rather than words comes the thought of high windows:

The sun-comprehending glass,

And beyond it, the deep blue air, that shows

Nothing, and is nowhere, and is endless.

We agree with Porter. It’s a perfect way of describing how Sgouros’s Remembered Landscapes make us feel.

Leave a Comment