Kinetic Sculptor Says “Wind Is the Ultimate Artist”

August 06, 2019

We interview kinetic sculptor Tim Prentice, whose work from the past forty years is on view at the Cornwall Library (Connecticut). For at least twenty of those years, Prentice has had macular degeneration.

Tim Prentice became captivated with kinetic sculpture as a young man when he visited the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts. In the museum’s entrance was a work by Alexander Calder. He stood in the lobby, transfixed, while his classmates toured the museum. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that after earning a degree in architecture from Yale and working as an architect for many years in New York City, Prentice “changed his major,” as he likes to say, and became a sculptor.

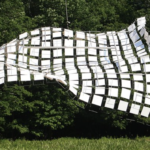

In his book Drawing On the Air, Prentice talks about how he’s driven to make machines that allow the “air to come along and do the art.” His ability to make the wind visible depends on mechanical aptitude, as well as his instinct for physics and materiality. His sculptures—made of lightweight materials resistant to erosion, ever ready to be set in motion—rustle and hum as they move. They reflect the changing light. While playful, they also evoke life’s poignant, timeless rhythms.

In addition to his smaller-scale sculptures, which are on view at the library, Prentice has spent the past 30 years doing commissioned work of large-scale sculptures for institutions both in the United States and abroad. His studio’s commissioned pieces can be found in such places as the Knight Cancer Research Building at Oregon Health and Science University (Portland, Oregon); the Sandy Hook Elementary School (Newtown, Connecticut); the Phaeno Science Center (Wolfsburg, Germany); and Union Depot (St. Paul, Minnesota). Two long-time assistants help him with this work: Dave Colbert (now Prentice’s corporate partner for large-scale commissioned works) and David Bean.

Interview: Tim Prentice

Inspirations

Phillips / Schumacher (V&AP): What are your inspirations?

Prentice: It’s all inspired by Calder and George Rickey. Calder put kinetic sculpture on the map. But he didn’t actually invent it. There were other earlier versions. Not so imaginative. The Russian Constructivists particularly. Calder was a storyteller and joked around. When serious students asked him, “Well, Mr. Calder, considering that your work is not symmetrical, how do you know it’s done?” he’d say, “When it’s dinnertime.” He hid behind his humor. He was not an intellectual—he was a people person. He had a lot of friends around here, because he lived and worked in Roxbury, Connecticut, not far from here.

He was jolly, nice. The lesson I got from him is that it’s okay for grown-ups to play. And then the question becomes, how can you turn that into a living? Playing for a living? Anyway, George Rickey comes along. He probably had Calder’s example in mind, but had a different experience. For example, Calder majored in engineering in college, but Rickey was the more instinctive engineer. He had a real instinct for engineering; his stuff is much more complex. He was also an intellectual. He taught all his life, he theorized, and he wrote what is probably the definitive book on the Constructivist Movement. I met Rickey and got to know him fairly well. I met both of them, but barely knew Calder.

So, anyway, the movement thing really hooked me, and they are the masters. And there’s some people out there these days doing kinetic stuff. But I don’t see anybody trying to claim new turf. Rickey moved away from Calder, and their stuff is utterly different. So, I thought if that’s possible, it may be possible to find yet more turf out there to claim.

V&AP: And do you feel like you have?

Prentice: I think so. Henry Moore said the point of life is to take an impossible task and devote your life to it.

V&AP: Did Rickey ever say anything to you about your work that you remember?

Prentice: One of the times I went to see George Rickey after I had quit architecture, I brought some of my early efforts to show him. And he looked at them for quite a while, and broke the silence with a statement like dropping a rock into a well: “Where are the limits?” he asked. And I drove off saying, “What the f— does he mean by that?” But I’ve been thinking about it over the years, and it’s been slowly dawning on me.

Studio and working process

V&AP: You have two full-time assistants and other local craftspeople you call on at times. Who does what?

Prentice: All of these years I’ve sort of hoped that there would be a balance, and the crew would take care of the big stuff (like building and installing large commissions), which would pay for me to make the small stuff with my own two teeny little hands. And to be an artist at a smaller scale but make everything myself [everything on view at the Cornwall Library was made by Prentice, without the help of his assistants].

It’s gotten to the point where that’s really happening. And so, I think, ah, all my life I’ve been waiting for this moment to try out some new ideas, and sit down at the piano bench, and what I’m finding is that the music doesn’t necessarily come all that easily. You wonder if you really have all that many good, new ideas. When I get frustrated, I go to the barn and see if I can find a piece that I can improve on. That’s my escape at the moment, because the barn’s full of stuff, as you’ll see.

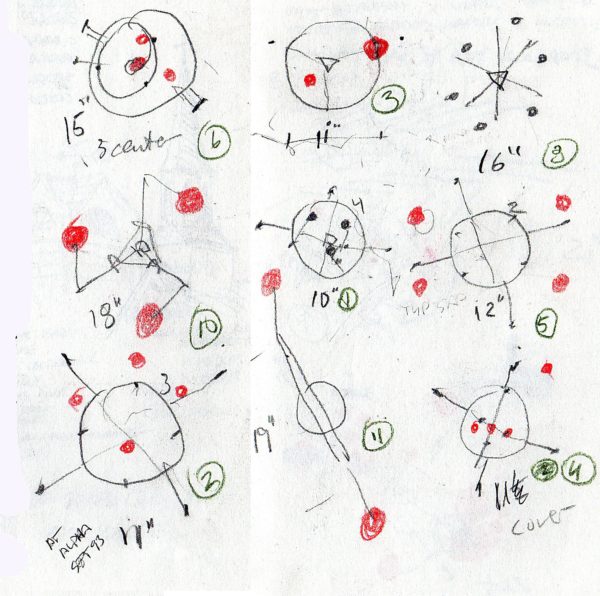

Kinetic sculpture typologies developed by Prentice

V&AP: So, you work on creating new pieces.

Prentice: I try to.

We’ve also developed generic types (that serve as the basis for new iterations). Zingers, which are long skinny things that catch the air and wiggle.

And then there are carpets, a surface like this table that’s supported from a single point, is very light, and can wobble in the air. And curl and twist. Which is easily done outside because the air is full of imagination and it never loses new ideas. The challenge is that you can’t leave it out on a windy day. If you get a thunderstorm, it would be wrecked.

A whole other subject is jokes, which is making things purely for the fun of it. There’s a joke behind you. That’s supposed to be Groucho. He’s been in too much rain and is rusted, but when the wind blows, his eyes go up and down. His eyelashes. That’s not, you know, that’s not moving the career forward.

Curtains are suspended from two or more points and can be set against a wall.

The wind is the ultimate artist theoretically. Even if it’s the slightest breeze.

The challenge (and joy) of kinetic sculpture: getting things to move

V&AP: How do you get movement indoors, where a lot of your sculptures are installed?

Prentice: Well, it’s more static indoors, though any space that’s inhabited is going to have air movement. But it’s really light. For example, if the sun shines in on a masonry floor, and heats up part of the floor, and not the other, that’s a convection oven. If there’s air conditioning, it’s obviously goes on and off on its own schedule. If there’s heat in the winter time, it’s fanned in. If there’s a window on one wall, as there often is in a corporate space, that glass is cold in the wintertime, and the air is rushing down and sliding close to the floor and going up the opposite wall. In the summertime the reverse is true. There are often fans of some kind. And, then, you sometimes get a lot of people sitting around a table, and, if you can imagine it, that creates an invisible mushroom cloud of rising air.

We’re giving off 230 British thermal units of energy just sitting here. And you get four, five people together—you can use that. I actually made a model of a very small piece in the shop one winter for some students who visited me. The shop was cool at the time, and I put my hand under the piece to show how it could move based on the warmth of my hand.

Vision loss

V&AP: When did you start losing your vision?

Prentice: Probably long before I noticed it, because when it just begins you don’t notice it. But certainly 20 years, could be 25 years ago. I’ve had macular degeneration for a long time. The only good thing about that is you sort of get used to the various descending levels. And you develop techniques and so on. Half of it you’re sort of hardly aware of. For years, I’d been going to my eye doctor once a year and getting my regular prescription, and then one day he looked in my eyes and said I had drusen [yellow deposits of lipids under the retina that can signal the development of macular degeneration].

He asked me what I did. I said I was a sculptor. He said, “you weld?” I said, “yeah.” He said, “Well, that’s it.” He was thinking of arc welding. I use a spot welder, and that isn’t it.

V&AP: Was there a point at which you became aware of your changing vision?

Prentice: We went out to Rhode Island one time. At some distance against the skyline was a boat with a great white light on it. For some reason, I noticed that I could see it with one eye and not the other eye. I played with that for a while, and I’d be a bit concerned and curious. And found out that if I looked not at the light, but a little bit up and a little to the left I could see it with the bad eye. You must have been through this with other people. The trouble with that is you’re not looking at the light. And your eye wants to go back and look at the light because you know it’s there, but you can’t, because you’re not giving it the center of your retina. So, it’s irresistible to go back to it, and of course when you go back to it, it vanishes.

When I went to a retinal specialist after learning about the drusen, I knew I’d be in the waiting room for a while, in New York this was, and I so stuffed a current issues of the New Yorker in my hip pocket all rolled up. At the doctor’s office, instead of all the sports magazines, I took out my New Yorker and read an article by a staff writer [Henry Grunwald] about getting macular degeneration and what he went through. I had the perfect article on that perfect subject that I was most passionate about at that precise moment by sheer fluke. I wrote him a letter thinking how pleased he’d be. He didn’t answer.

V&AP: So, it wasn’t the end for welding. Have you had to slowly adapt over time or did you have to change your working methods suddenly?

Prentice: Slowly. Everything slowly.

V&AP: At what point did you stop driving?

Prentice: Probably two years ago now. I used to go to a guy at a clinic in Waterbury, south in the state. Drive down and get my eyes dilated and then drive back in snow blindness on the road.

The good news was he would say come back in a year. And we mostly talked politics. Because I wasn’t, you know, sufficiently far enough along to be that interesting to him, I guess. Sometimes he said come back in six months because he was worried about something. One year when I called his office to make my appointment, it turned out he had died. So, my wife said I should go to her eye doctor. He was very nice, gave me all his own tests, and said you’re legally blind. Don’t you dare go to see that guy again, I told my wife. Unfortunately, she hasn’t been with us for about a year and a half now.

V&AP: I’m sorry.

Prentice: So, now I need somebody to drive for me, and grocery shop, and all that kind of stuff.

V&AP: That must be hard at times.

Prentice: Well, I’ve been saying all my life, the country’s great, but when you can’t drive you’re in a tight spot.

I have a kind of nanny. She’s the wife of the tall guy [Tim’s assistant, David Bean]. First off, she’s a terrific cook, and second off, she’s a terrific person, and third off, we agree on everything political. She’s kind enough to do the shopping and leaves me a lot of things to heat up. But sometimes I need a little more instruction, and I’m learning to cook crudely. And my friends, such as are left—because this area’s become kind of an old folk’s home—have a habit of, if they want to invite me for dinner, they invite a friend we have in common who lives nearby and can pick me and take me back. Or I have to get somebody to do it. Or the host has to do it. So, it’s a drag for everybody else. Well, fortunately I like it here. I’ve done a lot of traveling, so I don’t feel I need to go anywhere.

V&AP: Is it possible to describe what you see when you look at that sculpture over there hanging from the tree?

Prentice: Well, what I’m looking for is probably different than somebody else, because I’m looking to see how it’s doing in these conditions. It’s in a wind tunnel test. I want to know how tangled it’s going to get.

If a piece is going to be outside, it has to pass all the tests. Being able to move in light airs, being interesting, surviving all the thunderstorms, wearing well, and so on. This one here passes a lot of the tests, but is boring, so it going to go back into the shop, for example.

V&AP: Have any tools been particularly useful to you in the studio as you’ve worked with vision loss?

Prentice: I use four levels of magnification. And sometimes it’s easier to use the lowest level of magnification (as opposed to the highest), because the more you blow things up, the less context you have. And if you’re trying to get really inside something with a lot of detail—let’s say it’s wires coming together, which is in my case typical—you’ve got to know where they’re coming from, and what they’re doing, and why they’re there. Not just the precision of where they cross. You don’t see the wires any better with lower magnification. You see them less well, but you see them in context, which is often an advantage.

Materials that enhance the movement and durability of Prentice’s kinetic works of art

V&AP: When I encounter your pieces, the translucency and play of reflections is an important part of the experience. What kind of materials do you use to create your effects?

Prentice: We have three favorite materials—I like to call them colors. One is Lexan. Then we use aluminum and stainless steel, which I consider colors because they reflect everything. If you have a red dress on and walk by, you get red on the sculpture, and so on.

Prentice’s commissioned work for the new Sandy Hook Elementary School

V&AP: Which of your commissioned works are particularly meaningful to you?

Prentice: Designing our sculpture for the new Sandy Hook Elementary School was very meaningful because of the building and what happened there and because the architect, whom we had worked with before, approached us directly. He’s from New Haven, he’s terrific. He’s just the guy for that job because he’s a true believer in community spirit and involving everybody. All the people sitting around the table—he could pull them together and get them to agree.

He’s unique, as far as I know—and there may be others out there—because he’s also a sculptor, and makes sculpture for his buildings, as part of the construction. He does that for a lot of schools. So, he’s designing for kids mostly. And that’s something that fits with him.

So, we thought well, great. He had set up a wall of glass in a big entrance space, with large poles of aluminum tubing at slight angles like this against the glass, not structural. And they had smaller tubes coming out of them. It was a very abstract version of trees. No leaves. But very abstract, just suggestive. And they were silhouetted against the light on the other side of the glass. So, we said well, we’ll do the birds. Which we did. And we presented the birds. And there was a pause.

We’d made the birds out of Lexan, a poly carbon developed by GE to be impervious to the ill-effects of ultraviolet light that breaks down most plastics over time. And we’ve used it all over the country and abroad with no problem. But the fire department in Sandy Hook wouldn’t approve it. They didn’t think it was sufficiently fire resistant. And we had all these nice birds. I made a bunch of abstract birds thinking, we’re going to be abstract the way the trees are abstract. But they didn’t do anything for me. So, I gave them to the tall guy (David Bean), and he really knows his birds, so he made specific birds, beautiful. Some are left in the barn. And they were turned down.

In the end, we did a piece that hangs from the atrium’s ceiling and captures the reflections of stained glass windows.

V&AP: When I look at your sculptures, I become a little less anxious. There’s something about the movement that causes me to feel more still inside, I suppose. I wonder if that’s true of kinetic sculptures, in general?

Prentice: It’s interesting to hear you say that. It must be.

We did a piece in Portland, Oregon, in a cancer research center. I think it was last summer that Dave went to install it. I’ve gotten two letters in my life that blew me completely away, and one of them was from a cancer patient in that facility who said that when she looked at the piece, which is made of this light material, she imagined as she looked at those plates flapping around that she was seeing the cancer cells leaving her body. Then she said, “And the pain went away. It may not last, but I’m going to enjoy it for as long as I can.”

For more information on Tim Prentice, see www.timprentice.com.

Tim Prentice’s exhibition, “Gone With the Wind,” is open through August 17 at The Cornwall Library (30 Pine Street, Cornwall, Connecticut).

Leave a Comment