Haunted: Images of Blindness Plague Artists with Vision Loss

April 25, 2018

Macular degeneration has affected artists—and, by extension, art—for centuries. Trying to identify how is hard, in part because Western art is haunted by negative representations of blindness.

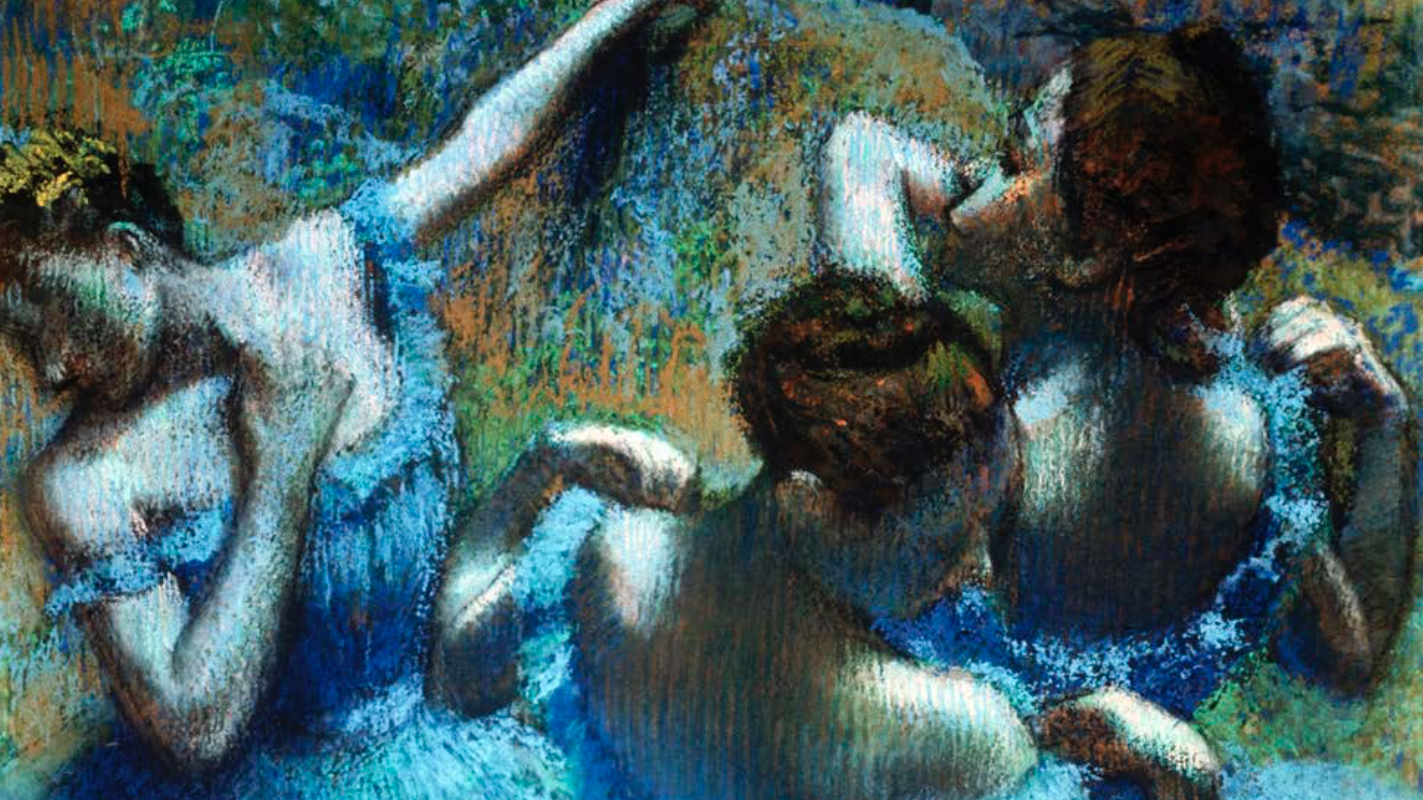

Through interviews, profiles, films, and an art exhibit my collaborator Brian Schumacher and I have curated for the University of Cincinnati, The Vision and Art Project brings attention to artists who have been affected by macular degeneration over the centuries, and, by extension, the powerful influence the disease has had on art. The radical improvisations of Titian and Degas’s late work, for instance, which deeply influenced subsequent generations of artists, were likely created under the influence of macular degeneration.

After more than five years of work on the project, however, the question of how macular degeneration affects art and artists seems even more complex than at the outset. Part of the reason is that many artists who acknowledge having macular degeneration downplay its effects on their work, even when their work, and working methods, have changed dramatically. Sometimes this is because types and degrees of blindness, as we have learned, are not fixed characteristics or even a simple matter of optics. Vision, rather, is an interconnected system involving the mechanics of the eye, the brain’s processing of sensory input, and the body’s kinesthetic experience of space. (Not to mention the role of imagination, memory, and experience in the act of seeing.) Given the complexity of vision and what it means to see, artists often don’t know just how poorly (or not) they see.

Beyond this, many artists also strive to downplay changes in their vision and to pass as sighted even when they are aware that their visual acuity is poor. This, in turn, obscures the presence of vision loss in the arts.

Artists sometimes have practical reasons for wanting to pass. They may worry that the perceived value of their work in light of vision loss might be diminished, or that their work might be misunderstood. A recent article in the Independent on De Kooning’s late work reflects that when older artists become disabled and their work changes, the question inevitably becomes: is this a late “flowering or failing”? Matisse’s late cut-outs aside, the art world often dismisses late work created under conditions of disability. This is especially true of work created by painters with vision problems, since the ability to paint is commonly thought to depend on acute vision.

Like many artists, poet Stephen Kuusisto tried to pass as sighted

For the first thirty-nine years of his life, the poet Stephen Kuusisto tried to pass as sighted. He explored this experience in his memoir, Planet of the Blind.

Kuusisto was born with a severe vision impediment called “retinopathy of prematurity” (ROP), more damaging among premature children in the 1950s and ’60s than it is today, since the condition is now better understood and treated. (The oxygen content in incubators in the 1950s and 60s was too high, which caused blood vessel overgrowth.) Though legally blind, Kuusisto is not completely without sight, which is true of most people who are blind, including those with macular degeneration. In Kuusisto’s case, he can see the world in “fragments,” as he says, “like a myopic, darting minnow.” These vestiges of sight made it possible for him to pass as sighted for the first four decades of his life—an effort, which he called an “impossible contest with the sighted world,” that was exhausting, depressing, isolating, and ultimately dangerous.

In western art, images of the powerless blind

In his memoir, Kuusisto makes it clear that images of the blind in our culture encouraged him to deny his condition for as long as possible. “Who would choose to be blind?” he asks. He preferred being “a wild white face, a body groping, the miner who’s come suddenly into the light… a jellyfish… amphibious” to being blind. To be blind was to be one of the blind men, who, in 1771, “were arranged in the village square of St. Ovide, all of them dressed like clowns, each wearing a dunce’s cap… people who unwittingly expose themselves, who can’t control their hands.” It was to be Mr. Magoo, a cartoon character developed in 1949 whose extreme near-sightedness leads to a series of comic misadventures.

As he and other writers have pointed out, blindness is a central subject and metaphor in Western art. Yet blind figures are rarely presented in positive ways. Instead, they are often depicted as helpless, unattractive, melancholy, insufficient and so forth. You see this in images from Bruegel’s Parable of the Blind Leading the Blind (1568) to Poussin’s Christ Healing the Blind at Jericho (1651), Degas’s Portrait of Estelle Musson (1865), and Paul Strand’s The Blind Woman (1916). Artists struggling with vision problems are often acutely aware that their condition aligns them more closely with the powerless (blind) subject of representation in art, than with the masterful maker of images.

The positive example of blind writers

To counterbalance these negative representations of blindness that haunted him, Kuusisto turned to blind writers, many of whom are represented in positive terms. If he slyly warns us against seeing any clichéd affinity between himself and famous blind writers (“I’m a blind wretch… Milton without daughters!” he says in an imaginary conversation with Evelyn Wood, the American educator who developed what’s known as speedreading), nevertheless he aligns himself with such writers to assuage his anxieties about reading and writing as a blind man.

He turns for courage to the hall of blind writers, for instance, in a scene he relates from his graduate school years at the University of Iowa, where he was pursuing an MFA in poetry. When he decides uncharacteristically to admit his disability and asks a professor for more time to complete an assignment because vision loss makes it hard for him to read, he is informed that, if he can’t complete his work, he shouldn’t be in graduate school. To which Kuusisto retorts, “And I suppose Milton, Homer, James Joyce, they couldn’t have taken a course in this department either?”

His identification with Milton et al does not help him out on this occasion—the professor tells him he shouldn’t be in the class and Kuusisto becomes sick with distress. But as Kuusisto has gone on in his career, he has overtly identified with blind writers as a source of inspiration, insight, and positive self-identification. His 2013 book of poems, Letters to Borges, speaks directly of and to the blind Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges. Another low-vision writer, Emily Dickinson, serves as the subject of Kuusisto’s first poem in Letters, “Emily Dickinson and the Ophthalmoscope.” “A bird, dun-colored and nearly bald, flits above the retina and vanishes Like a Calvinist toy—a straw doll lost in snow…/‘I am a girl going blind,’ she thinks. ‘Soon I will be dark as a hat/Or something we might lace.’”

Unlike a blind writer, a blind painter has few examples to turn to

Though blind painters exist (and always have), they have tended to hide or elide this fact, a sign of just how longstanding and pervasive the stigma of blindness is for an artist.

When Vasari visited Titian’s studio late in the artist’s life, at which point he could no longer see well, quite likely because of macular degeneration, Vasari dismissed Titian’s late paintings as dark and indecipherable. He wrote: “[Titian] would have done well in his last years not to have worked except as a pastime to avoid damaging with less skillful works the reputation he earned in his best years before his natural gifts had begun to decline.” The artist Georgia O’Keeffe was deeply secretive about her vision loss, and, while Degas often discussed his visual difficulties in letters and with friends, art historians and critics since then have tended to avoid linking Degas’s choices and output as an artist with his struggle to see. In 1923, Walter Sickert could write based on firsthand observation of Degas’s working methods that:

It was natural that, during the years when I knew him, from ’83 onwards, he should sometimes have spoken of the torment that it was to draw, when he could only see around the spot at which he was looking, and never the spot itself… It may safely be said that the curious and unique development of the art of pastel that this obstacle compelled him to evolve would not have come into being but for his affliction. A larger scale became a necessity. For the shiny medium of oil-paint was substituted the flat one of pastel. Minute delicacies of detailed execution had to be abandoned. A very natural dread that the affliction might grow made, of the necessary delays that oil-painting exacts, an intolerable anxiety. A pastel is always ready to be gone on with.

Whereas in 2015, the painter Lennart Anderson, himself affected by vision loss, said:“I guess Degas had eye trouble, but no one really knows.”

Many visual artists feel dependent on visual acuity

For the artist whose career has been built on seeing, whose life has been devoted to translating or transposing the seen world onto the canvas, the problem is not only that there seem to be so few examples of artists who worked fruitfully under conditions of vision loss. Another issue is that insight has been dependent on visual perception. In the parlance of disability studies, insight has been opthocentric. Similarly, assessing a painting as one is working has been dependent on visual perception. Thus, when visual perception becomes “flawed,” the painter often struggles with a feeling of no longer having the ability to work.

This is not true for the writer. In Planet of the Blind, Kuusisto notes that as Borges walked through an arcade in Buenos Aires each day, he would narrate what he saw, and “told funny, involuted, decorous stories about the world that he would invent as a means of navigating the hours.” For Borges, in other words, blindness was not absence or lack, but a vital space for the imagination, lending itself to his vocation. Kuusisto, too, makes abundantly clear that his blindness caused him to pass easily and deeply into imagined worlds, which we cannot understand as anything but a gift to him as a writer.

Indeed, as Kuusisto emphasizes again and again—impaired sight can lead to extraordinary visions, insights, and lyrical associations that are the basis of writerly insight. In a 2009 interview, he discusses at some length how the type of seeing that is the province of poetry is fueled by the imagination, and is “often concerned with things we cannot see, as Federico García Lorca or Dylan Thomas will tell you.” He explains in this interview that, to do his work and “follow the deep roads of the guitar,” it is not necessary to see.

The blind artist, too, has extraordinary inner resources, but they are not as readily evident amid the scrim of negative associations. Serge Hollerbach speaks of drawing on his “third eye,” which for him is “something that your spirit, or your mind, or your soul, sees.” William Thon spoke of the presence of instinct and feeling that allows an artist to work like a sailor does, by “throwing his bowline in the dark.” Dahlov Ipcar spoke of the hand knowing what line to draw from long experience and body memory. Doris Salcedo talks about how art is a way of thinking and in order to think you do not need perfect vision.

Because macular degeneration generally strikes late in life, few artists with the condition have as many decades as Kuusisto did to make their peace with vision loss and adapt. In their remaining years, some artists try to pass as sighted. But most, whether they openly admit it or not, are forced to embrace the realities of their disability, if only reluctantly, in order to continue painting.

Artist and caricaturist David Levine’s struggle to pass as sighted

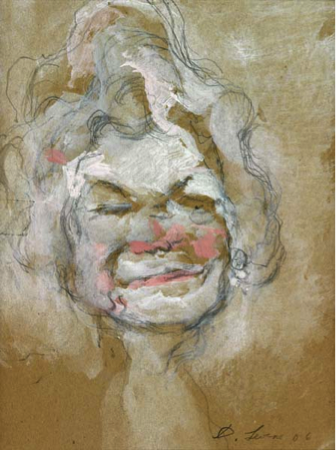

The great caricaturist and painter David Levine is an example of an artist who at first tried to hide his failing vision and work in the opthocentric manner that he always had, with his extraordinarily keen eye on the world.

Though it is not the purported subject of the film, the 2008 HBO documentary Portraits of a Lady deftly illustrates the difficult aesthetic and emotional terrain loss of sight can create in an artist’s life. The film captures David Levine painting Supreme Court Associate Sandra Day O’Connor as part of the Painting Group, a weekly gathering of artists that he and Aaron Shikler had started in the 1950s. Levine had been diagnosed with macular degeneration a year and a half before, but had been relatively secretive about his condition.

For six hours, Justice O’Connor sat for the group. Levine was one of twenty-five artists who were drawing and painting her, but, along with Shikler, he was the most notable artist in the room. When the camera focuses on Levine in the first half hour of the film, it shows him critiquing painters’ work-in-progress. (Levine and Shikler had started the Painting Group as a way of teaching, and divided their time at the weekly sessions between painting and teaching.) As Levine circles the room talking with students, what we hear him say wouldn’t suggest he is struggling with his vision. He seems to see well enough to give astute advice.

In contrast, partway through the film, Levine is shown in the early stages of working on a charcoal drawing of O’Connor. He is struggling.

The film’s producer, David Hume Kennerly, took pictures of O’Connor from each painter’s vantage point so they could finish their portraits from photographs if they weren’t able to from life. In his private studio, David Levine produced the following portrait, relying as much on his instincts as a caricaturist as on his remaining sight.

It was displayed, as were all the Painting Group members’ O’Connor portraits, at the National Portrait Gallery in 2007. The last part of the film focuses on the show’s opening. The Painting Group members are there. O’Connor is there. Many literary, artistic, and political luminaries are present. All were intensely interested in Levine’s portrait, which to some degree became the subject of a joke.

“This one takes the beauty prize,” O’Connor says.

“Oh, that’s how I feel about you when you and I are dissenting,” Justice David Souter says to O’Connor.

“That captures something about Sandra, but it’s not exactly what she looks like,” Justice Stephen Breyer says.

Trying to laugh it off, Levine says to O’Connor: “I’m as surprised by this as you are.”

Aaron Shikler says: “What David Levine did was make something out of what he couldn’t see anymore, and that is what is exciting about it.”

Not long after the opening, Levine’s blindness became very public when Vanity Fair published an article about the change in his caricatures and his departure from The New York Review of Books, which forced him to retire.

Levine adapts to partial vision

Feeling isolated in the last year or so of his life, Levine left behind the descriptive mode of his caricatures, which had made him famous but had become impossible and a source of embarrassment in the face of impaired vision. He instead devoted himself entirely to the more lyrical and forgiving mode of his paintings.

His final unfinished painting is of a mass of bathers at Coney Island, a familiar subject in his work but one that has been transmuted by mystery and the emotional vision of memory.

It makes one think of an epigraph from Borges in Kuusisto’s book of poetry—“Now is a tree or a god there, showing through the rusty gate?”—or of any of a number of the mystical analogies Kuusisto discovers in his blind exploration of the world, wherein a bar becomes a “tangled translucence,” where air has turned to “hand-blown glass,” where a “scratched soul” rises from a piece of pottery. It is a lyric mode that may not be natural to a painter who has long been guided by acute perception, but it shows itself to be available. It tells us that there is a beauty and value not only in mastery, acuity, and sight, but in that which is forged out of vulnerability, incompleteness, hesitation, and uncertainty born of the trying.

Comments

Quite amazing and inspiring from so many angles. As I read this I think of Sargy Mann, an English painter who struggled with his eyesight for years, and eventually went blind. Paintings produced after that were lauded as his best. He himself wrote and talked about his artist’s vision and how the absence of physical sight may have been what allowed him to exceed limits he had imposed on himself.

Mann, P. (Ed.). (2016). Sargy Mann: Perceptual systems, an inexhaustible reservoir of information and the importance of art. Thoughts toward a talk. London: SP Books.

Mann, P., & Mann, S. (2008). Sargy Mann: “Probably the Best Blind Painter in Peckham.” SP Books. Retrieved from http://www.petermannpictures.com

Just saw the last comment….. Anyone interested in my father is much better off going to http://www.sargymannarchive.com than to my site ! Congratulations to everyone involved in this project, its a fascinating and in my opinion important subject.

Leave a Comment